RSS

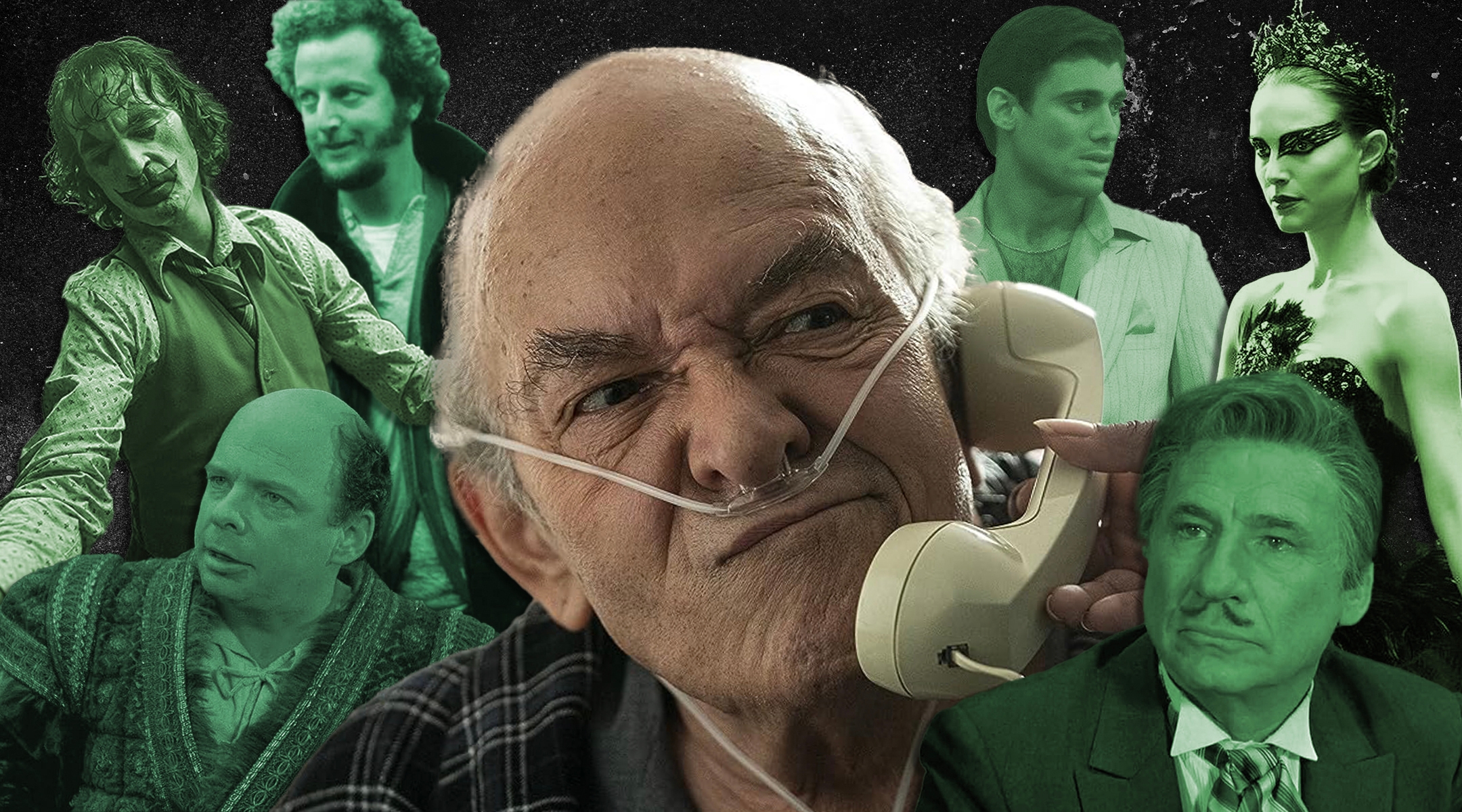

The best villains played by Jewish actors

(JTA) — The film and TV world recently lost two Jewish actors who were not household names but were acclaimed for a pair of signature villainous roles.

Last month, Mark Margolis passed away following a career on stage and screen that spanned over 60 years. He studied with and was later the personal assistant of renowned acting teacher Stella Adler before appearing in “Scarface,” HBO’s “Oz” and multiple films by the acclaimed Jewish director Darren Aronofsky.

But he was most remembered for his Emmy-nominated performance as Hector Salamanca, the wheelchair-bound, largely non-verbal patriarch of a Mexican crime family in “Breaking Bad” and “Better Call Saul.” One could argue that Margolis, whose family “started a couple of Reform synagogues,” embodied one of the most well-known villains ever portrayed by a Jewish actor.

Later in the month, Arleen Sorkin died of pneumonia after a years-long struggle with multiple sclerosis. Possessing a unique comic sensibility, she was in the mid-80’s cast on “Days of Our Lives” as Calliope Jones — a quirky fashion designer based loosely on Cyndi Lauper. That character inspired Paul Dini, a writer on “Batman: The Animated Series,” to create the character of Harley Quinn — a jester-like henchwoman for The Joker, who would be voiced by Sorkin for nearly 20 years. Since Sorkin played Harley Quinn with an exaggerated version of her Brooklyn Jewish accent, the character became canonically Jewish as well.

Thanks in large part to Sorkin’s larger-than-life personality, Harley Quinn became so popular that she made the rare jump from animated series to comic books to live action films and has remained a uniquely endearing super-villain.

In memory of Margolis and Sorkin, and in tribute to the fantastically sinister characters they embodied, here’s a quick survey of some of the other noteworthy villains played by Jewish actors on screen.

Daniel Day-Lewis — “There Will Be Blood” and “Gangs of New York”

Three-time Oscar-winner Daniel Day-Lewis learned at an early age that acting was an effective way to deal with schoolmates’ bullying that came from being an outsider on both sides of his family — Irish on his father’s, Jewish on his mother’s. On screen, Day-Lewis masterfully embodied two of cinema’s most deliciously villainous characters: Oil tycoon Daniel Plainview (for which he won the Oscar for best actor) in “There Will Be Blood” and nativist gang leader Bill “The Butcher” Cutting (for which he was nominated for best actor). Both characters embody the darkest sides of the American dream, and no one has ever made a milkshake sound more menacing.

David Proval — “The Sopranos”

Before playing Toby Ziegler’s Rabbi on “The West Wing,” Jewish actor David Proval played many Italians on screen, from Tony in Martin Scorsese’s “Mean Streets” to Hunk Pepitone on “Fame” to perhaps his most memorable role: Richie Aprile, the ruthless, sadistic capo of the DiMeo crime family on “The Sopranos.”

Martin Kove — “The Karate Kid”

John Kreese, the original Cobra Kai sensei played by the Jewish Brooklynite Kove, was one of the most well-known 1980s bad guys.

Michael Douglas — “Wall Street”

“Greed is good,” says Gordon Gekko in this classic indictment of 1980s Wall Street culture. So was Douglas’ performance, which earned him an Academy Award in 1988.

Kirk Douglas — “The Villain”

Michael’s father, the legendary actor and two-time bar mitzvah boy Kirk Douglas, was often the hero on screen. But he tried his hand at playing the bad guy in this ridiculous, forgettable Western comedy from 1979.

Joan Collins — “Dynasty”

The acclaimed role of Alexis Carrington, the scheming ex-wife of the wealthy Denver oil magnate Blake Carrington, helped catapult the soap opera “Dynasty” to the top of the ratings. The Emmy-nominated Collins made Alexis a multi-dimensional character that frequently cracks the upper echelons of “greatest villains of all time” lists and inspired a bevy of prime-time imitators. Her father was Jewish and proudly identified as a member of the tribe.

Daniel Stern — “Home Alone”

Who could forget Daniel Stern’s iconic shenanigans as Marv Murchins, one half of the inept duo that fails to take on the wily kid Kevin McCallister in the “Home Alone” series?

Mel Brooks and Rick Moranis — “Spaceballs”

These two comedy legends put in hilarious performances as Dark Helmet and President Skroob — the bungling bad guys of Brooks’ 1987 “Star Wars” parody.

Wallace Shawn — “The Princess Bride”

The year 1987 also saw Wallace Shawn play the sinister Sicilian Vizzini to comic perfection in this silly classic.

Dustin Hoffman — “Hook”

Hoffman played the infamous Captain Hook in the eponymous 1991 Spielberg film, which critics (and later Spielberg himself) wrote off as a failure.

Joseph Wiseman — “Dr. No”

Plotting from his island lair, Joseph Wiseman’s Julius No was the first, and one of the best ever, to portray a James Bond villain on screen. The Canadian Encyclopedia notes: “Despite his on-screen performances as the ‘heavy,’ Joseph Wiseman was a Jewish scholar who travelled extensively, giving readings from Yiddish and Jewish literature.”

Yaphet Kotto — “Live and Let Die”

Years later, the proud Jew Yaphet Kotto played another Bond villain heavily influenced (in a cringe-worthy way by modern standards) by the Blaxploitation era: Dr. Kananga/Mr. Big, a ruthless drug baron and Caribbean dictator. Kotto’s Cameroonian father was Jewish, and his mother converted to Judaism.

Jesse Eisenberg — “Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice”

James Bond isn’t the only IP with memorable villains portrayed by Jewish actors — several villains in the Marvel and DC comic universes have been played by Jewish actors as well. The normally quiet-tempered Eisenberg played Superman’s archenemy Lex Luthor in a 2016 blockbuster (and Michael Rosenbaum portrayed the character on the TV show “Smallville”). Some fans might also call Eisenberg’s Mark Zuckerberg portrayal a villain in David Fincher’s hit “The Social Network.”

(Although no Jewish actors have ever played Magneto, Marvel’s most significant Jewish villain, a small handful of prominent Jewish actors have played other Marvel villains, from Jake Gyllenhaal’s Mysterio in “Spider-Man: Far From Home” to Corey Stoll’s humorous version of M.O.D.O.K. in “Ant-Man and the Wasp: Quantumania.” Jeff Goldblum also gave a memorable turn as Grandmaster in “Thor: Ragnorok.”)

Steven Bauer — “Breaking Bad” and “Better Call Saul”

We would be remiss not to mention another actor from the “Breaking Bad” franchise: Steven Bauer, whose Jewish maternal grandfather had fled Germany to escape Nazi persecution, settling in Havana. He plays the ruthless drug cartel leader Eladio Vuente.

Like Margolis, Bauer also appeared in “Scarface” (co-starring as Pacino’s best friend, drug-lord Manny Ribera). Unlike Margolis, Bauer is actually fluent in Spanish. He also learned Hebrew to play an ex-Mossad agent on Liev Schreiber’s “Ray Donovan,” as he had done decades earlier when he starred in “Sword of Gideon,” a Canadian film that was the template for Spielberg’s “Munich.”

—

The post The best villains played by Jewish actors appeared first on Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

RSS

After False Dawns, Gazans Hope Trump Will Force End to Two-Year-Old War

Palestinians walk past a residential building destroyed in previous Israeli strikes, after Hamas agreed to release hostages and accept some other terms in a US plan to end the war, in Nuseirat, central Gaza Strip October 4, 2025. Photo: REUTERS/Mahmoud Issa

Exhausted Palestinians in Gaza clung to hopes on Saturday that US President Donald Trump would keep up pressure on Israel to end a two-year-old war that has killed tens of thousands and displaced the entire population of more than two million.

Hamas’ declaration that it was ready to hand over hostages and accept some terms of Trump’s plan to end the conflict while calling for more talks on several key issues was greeted with relief in the enclave, where most homes are now in ruins.

“It’s happy news, it saves those who are still alive,” said 32-year-old Saoud Qarneyta, reacting to Hamas’ response and Trump’s intervention. “This is enough. Houses have been damaged, everything has been damaged, what is left? Nothing.”

GAZAN RESIDENT HOPES ‘WE WILL BE DONE WITH WARS’

Ismail Zayda, 40, a father of three, displaced from a suburb in northern Gaza City where Israel launched a full-scale ground operation last month, said: “We want President Trump to keep pushing for an end to the war, if this chance is lost, it means that Gaza City will be destroyed by Israel and we might not survive.

“Enough, two years of bombardment, death and starvation. Enough,” he told Reuters on a social media chat.

“God willing this will be the last war. We will hopefully be done with the wars,” said 59-year-old Ali Ahmad, speaking in one of the tented camps where most Palestinians now live.

“We urge all sides not to backtrack. Every day of delay costs lives in Gaza, it is not just time wasted, lives get wasted too,” said Tamer Al-Burai, a Gaza City businessman displaced with members of his family in central Gaza Strip.

After two previous ceasefires — one near the start of the war and another earlier this year — lasted only a few weeks, he said; “I am very optimistic this time, maybe Trump’s seeking to be remembered as a man of peace, will bring us real peace this time.”

RESIDENT WORRIES THAT NETANYAHU WILL ‘SABOTAGE’ DEAL

Some voiced hopes of returning to their homes, but the Israeli military issued a fresh warning to Gazans on Saturday to stay out of Gaza City, describing it as a “dangerous combat zone.”

Gazans have faced previous false dawns during the past two years, when Trump and others declared at several points during on-off negotiations between Hamas, Israel and Arab and US mediators that a deal was close, only for war to rage on.

“Will it happen? Can we trust Trump? Maybe we trust Trump, but will Netanyahu abide this time? He has always sabotaged everything and continued the war. I hope he ends it now,” said Aya, 31, who was displaced with her family to Deir Al-Balah in the central Gaza Strip.

She added: “Maybe there is a chance the war ends at October 7, two years after it began.”

RSS

Mass Rally in Rome on Fourth Day of Italy’s Pro-Palestinian Protests

A Pro-Palestinian demonstrator waves a Palestinian flag during a national protest for Gaza in Rome, Italy, October 4, 2025. Photo: REUTERS/Claudia Greco

Large crowds assembled in central Rome on Saturday for the fourth straight day of protests in Italy since Israel intercepted an international flotilla trying to deliver aid to Gaza, and detained its activists.

People holding banners and Palestinian flags, chanting “Free Palestine” and other slogans, filed past the Colosseum, taking part in a march that organizers hoped would attract at least 1 million people.

“I’m here with a lot of other friends because I think it is important for us all to mobilize individually,” Francesco Galtieri, a 65-year-old musician from Rome, said. “If we don’t all mobilize, then nothing will change.”

Since Israel started blocking the flotilla late on Wednesday, protests have sprung up across Europe and in other parts of the world, but in Italy they have been a daily occurrence, in multiple cities.

On Friday, unions called a general strike in support of the flotilla, with demonstrations across the country that attracted more than 2 million, according to organizers. The interior ministry estimated attendance at around 400,000.

Italy’s right-wing government has been critical of the protests, with Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni suggesting that people would skip work for Gaza just as an excuse for a longer weekend break.

On Saturday, Meloni blamed protesters for insulting graffiti that appeared on a statue of the late Pope John Paul II outside Rome’s main train station, where Pro-Palestinian groups have been holding a protest picket.

“They say they are taking to the streets for peace, but then they insult the memory of a man who was a true defender and builder of peace. A shameful act committed by people blinded by ideology,” she said in a statement.

Israel launched its Gaza offensive after Hamas terrorists staged a cross border attack on October 7, 2023, killing some 1,200 people and taking 251 people hostage.

RSS

Hamas Says It Agrees to Release All Israeli Hostages Under Trump Gaza Plan

Smoke rises during an Israeli military operation in Gaza City, as seen from the central Gaza Strip, October 2, 2025. Photo: REUTERS/Dawoud Abu Alkas

Hamas said on Friday it had agreed to release all Israeli hostages, alive or dead, under the terms of US President Donald Trump’s Gaza proposal, and signaled readiness to immediately enter mediated negotiations to discuss the details.