Uncategorized

One was born Catholic, another was a West Virginia Protestant — now they’re all making Jewish art

In artist Yona Verwer’s “Immersion VIII,” a nude woman in a fetal position floats in a swirl of water. The image is at once ethereal and surreal, not unlike Verwer’s first mikveh experience, a purification ritual, and central to conversion, the transition from non-Jew to Jew.

“It is the joy of weightlessness and the feeling of being spiritually elevated,” said Verwer, the co-founder of the Jewish Art Salon, who was born Catholic in the Netherlands and converted to Judaism in 1995.

“Five years after my conversion I started including Jewish subject matter in my paintings, that is to say contemporary visual interpretations of ancient texts,” she added. “I also examine contemporary themes like identity, ecology, antisemitism and more through a Jewish lens.”

“Immersion VIII” is one of 17 works in an original and perhaps unprecedented exhibit, “Children of Ruth: Artists Choosing Judaism,” currently running at the Heller Museum at Hebrew Union College. The thought provoking display features the paintings, drawings, collages, found objects and sculptures created by artists who have discovered a home through conversion. Some of the pieces are abstract, others representational and still others combinations thereof or not readily definable at all. None of it is kitschy, reductive or derivative.

Hailing from across the globe and representing an array of ethnic, social and religious backgrounds, all the artists have forged work informed by various aspects of their conversions. There is commentary on biblical texts, illustrations of Jewish rituals and others that merge imagery from the artists’ early backgrounds with representations of and metaphors for Judaism and Jewish life. In more than a few pieces, the Golem — the ultimate outlier who is nevertheless the mystical protector of the Jewish people — makes an appearance.

“I wanted to be Jewish from the time I was 11 despite knowing almost nothing about Judaism, and not meeting a Jew until I was 19,” Verwer said. “It felt irrational, but later, the Lubavitcher Rebbe’s words resonated — that sincere converts to Judaism possess an inherent Jewish soul, even prior to their formal conversion. In other words, converts are not outsiders but returning kin.”

The reasons for the artists’ conversions run the gamut. Kate Hendrickson grew up in West Virginia, the child of Protestants. Her mother was a choral director and organist and her father sang in the choir in both Presbyterian and Methodist churches. Neither parent was doctrinaire in their beliefs.

“I couldn’t buy Christian dogma at all or the idea that Jesus was the savior,” she said. “I married a Sephardic Jew who was raised in Morocco. His family embraced me, especially his mother. I used to follow her around in the kitchen, studying her recipes. When she died at 97, I felt ungrounded and wanted to explore Judaism. The rabbi suggested I do independent study and I attended services. Still, I wondered when I would become Jewish. A friend, another convert, said that she just woke up one morning and knew she was a Jew. The rabbi said, ‘Anytime will be a good time for you.’ I love Judaism because it feels so open-ended. It feels like home.”

In “Concealed Faith,” Hendrickson’s first series of post-conversion drawings, Hebrew letters, which are an integral part of her Cubist designs, are concealed. In the series that followed, “Faith Revealed,” Hebrew letters are even more central to the aesthetic and more clearly visible, at least to the attuned eye. Further, Hebrew letters inform the way she creates her art.

Hendrickson translates the title of each work into Hebrew, then creates cut-outs of each Hebrew letter.

“I rub graphite over the cut-outs and then randomly drop them onto my paper and rub them across the drawing, their edges and curves serving as structures for the composition.”

A number of the artists said Judaism appealed to them because of its openness to interpretation and reinterpretation, adding how much they valued the chance to express unexpected or even controversial viewpoints in their imagery.

Artist Mike Cockrill, a social justice advocate who has studied Torah for two decades, puts forth a feminist vision in his piece, “Excavation,” which reinvents Judaism’s patriarchal tradition.

Here, two women, posed in a manner that hints at Egyptian forms, are engaged in a metaphorical excavation. One holds a book, while the other, paintbrush in hand “is ready to repaint, rewrite, the traditional history from which she may have been excluded or been misrepresented,” he said. “Patriarchy lies at the women’s feet in the form of a blindfolded and disembodied head.”

Before Cockrill’s formal conversion, many of his paintings embodied an Americana vernacular, at times a tad mocking. During his Torah study period, his paintings made a radical shift, embracing an aesthetic that addressed the human condition, “the existential man, the meaning of life, which is funny but also dark,” he said.

“The rabbi who converted me was concerned that conversion would affect my painting in a negative way, that I would be doing Jewish kitsch,” he recalled. “I want to embrace my Judaism without pandering or being obvious and corny.”

Other artists combine ethnic or cultural elements of their pre- and post- conversion lives. Carol Man forged a design that couples Hebrew and Chinese calligraphy. Vicky Vogl, the daughter of an Ecuadorian mother and Czechoslovakian Jewish father, created an exquisitely detailed puppet theater depicting a Golem in a setting that also embraces a Latino aesthetic.

“The clock has Hebrew letters and the hands move counterclockwise,” she said. “The colors and craftsmanship are Ecuadorian and European.”

The genesis of this exhibit was almost a fluke. Curator Nancy Mantell recalled that at an earlier exhibit about the Torah, one artist revealed that she was Norwegian, had converted to Judaism, and was working on a textile project based on Torah portions. “We were so impressed by her commitment to her Jewish learning it made us start thinking, ‘Wow, are there other artists who have joined the Jewish people and have Jewish themes in their art?’” Mantell recorded.

She and Susan Picker, the assistant curator, put out a request for submissions. Throughout the process of choosing submissions, Picker says she was taken with the artists’ “love of Judaism and a sense of return to their deepest souls, with a love of grappling with Jewish texts.”

Alan Hobscheid, who grew up in Chicago, the son of a lapsed Catholic father and Japanese mother, became exposed to Judaism in college through friends and later married a Jewish woman. To some degree his conversion was expedient and, simultaneously, an expression of osmosis, he admitted. But, also, he stressed he always had a curiosity about Judaism.

As a convert he was especially drawn to the way that “Judaism doesn’t sugar coat or obfuscate God’s relationship to man,” he said. “The doubt and skepticism spoke to me. So does the duality in many of the customs, such as the cleaning up and preparation for Passover. It’s very serious, but there are fun elements.”

Still, in his oil painting, “Bedikat Chametz,” the literal darkness of that pre-Pesach ritual especially spoke to him. The painting portrays a man on the floor in a darkened space, scrounging around, searching for the last bits of leavened bread in order to dispose of it.

“It’s not despairing at all,” said Hobscheid. “There’s a beauty in it and conversion is a similar process. You must leave something behind in order to move on to something else.”

“Children of Ruth” runs through Feb. 26 at the Heller Museum at Hebrew Union College.

The post One was born Catholic, another was a West Virginia Protestant — now they’re all making Jewish art appeared first on The Forward.

Uncategorized

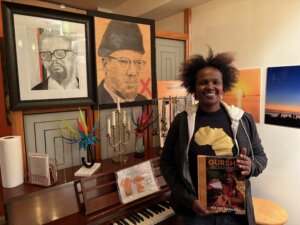

Ethiopian-American Jews lament loss of Harlem restaurant hub

For over a decade, Tsion Cafe, which owner Beejhy Barhany believes is the only Ethiopian Jewish restaurant in America, introduced patrons to injera, shakshuka spiced with berbere, and the flavors of Ethiopian-Jewish cuisine. But more than that, it introduced many patrons to Ethiopian Jews for the first time.

“I’ve been the ambassador, willingly or unwillingly,” Barhany said. “On the forefront, bringing and pushing for Jewish diversity.”

She recalled a moment that, for her, encapsulates the spirit of Tsion Cafe: feeding gursha — the Ethiopian tradition of placing food directly into someone’s mouth as a gesture of love — to an elderly Ashkenazi Jewish woman.

“She was open to receiving it! Someone who would never eat with their fingers,” Barhany said, laughing. “And she couldn’t stop.”

For Ethiopian Jews in America, a community numbering only a few hundred, Tsion Cafe was one of the only public-facing outposts of their heritage. But earlier this month, Barhany, who has been serving up Ethiopian Jewish delicacies to the Harlem community since 2014, announced on Instagram that she would close the restaurant’s dining room for “security reasons,” a move first reported by the New York Jewish Week.

Barhany told the Forward she has received “a lot of hate, phone calls, harassment,” including someone scrawling a swastika on the front of the restaurant. “You kind of push it aside, you disregard it. But at the end of the day, there is an impact emotionally, and it becomes a burden. I said to myself, ‘You know what? It’s just not worth it. It’s too much to deal with.’”

Despite the closure, Barhany remains determined to continue to share Ethiopian Jewish culture with patrons through catering and private events. “We are pivoting for security reasons because we have been threatened,” she said. “It’s not gone. We are reinventing ourselves. We are not giving up.”

The ‘October 8th Impact’

Barhany was born in Ethiopia and spent three years in a Sudanese refugee camp before moving to Israel in 1983, where she later served in the Israeli Defense Forces — a path shared by many Ethiopian Jews of her generation.

Ethiopian Jews lived for centuries in Ethiopia, maintaining ancient Jewish traditions and largely isolated from the broader Jewish world. In the 1980s and early 1990s, amid widespread instability in Ethiopia, Israel carried out dramatic covert airlift operations which brought tens of thousands of Ethiopian Jews to Israel. For many, their connection to Israel is rooted not only in longstanding religious tradition, but also in the lived experience of those rescue missions.

“Ethiopian Jews are very loyal to Jerusalem and to the people of Israel,” said Dr. Ephraim Isaac, an Ethiopian Jewish scholar based in New Jersey. “All the Ethiopian Jews I know living in America have relatives in Israel, and they go back and forth.”

When she arrived in New York in the early 2000s, Barhany was struck by how little awareness Americans had of the African Jewish diaspora. Wanting to educate her new neighbors about her background, and searching for a sense of “community and belonging,” she opened Tsion Cafe in 2014.

After the violent attacks on Israelis on October 7, 2023, Barhany said she felt the desire to be more public about her Judaism and her connection to Israel. “It was that October 8th impact. You just wanted to be a proud Jew,” she said. That impulse pushed her to make Tsion Cafe fully kosher and vegan. “I thought, ‘How can I have my people come here and feel comfortable?’ And also introduce Ethiopian food to people who never had it before.”

She also became more outspoken about her Jewish heritage and her connection to Israel, appearing in cooking videos with popular pro-Israel influencer Noa Tishby, and posting photos of herself at a pro-Israel rally shortly after the October 7 attacks. As pro-Palestinian protests unfolded across New York City, particularly on nearby college campuses like Columbia University, she said she understood that her outspokenness could make her a target.

But for Barhany, there was no other option. “I celebrated proudly and amplify my identity. I never shy away from that,” she said. “Otherwise I wouldn’t be true to myself.” She says her advocacy “happened organically, sincerely, genuinely, because who I am.” “I didn’t sign up for this,” she said, laughing. “But I am happy to engage with those people and maybe broaden their understanding of Jewish Diaspora.”

A small community, a singular space

For many in the United States’ small Ethiopian Jewish community, Tsion Cafe’s closure represents more than a business shift; it marks the disappearance of one of the only visible spaces representing their culture in America.

Isaac estimates the Ethiopian Jewish population in America numbers only a few hundred.“They came here just like other members of Israeli society,” he said, for education, work, or opportunity. Some say they came to the U.S. to get away from discrimination they experienced in Israel. The largest cluster, he noted, is in Jersey City, with smaller communities in Brooklyn and Queens. “We respect each other, we love each other, but never lost contact,” he said.

Barhany said that for many in the American Ethiopian Jewish community, Tsion Cafe was seen as “a home far away from home” with community members traveling from across the country to come to her restaurant. “We have people coming from D.C., L.A., you name it,” she said.

“I think a majority of Ethiopian Jews in America know Beejhy,” Isaac remarked. “The community is very upset by the closure. She is respected for all the efforts that she has undertaken.”

Tali Aynalem, a 34-year-old Ethiopian Jew who lives in Oregon, said Tsion Cafe challenged longstanding assumptions about what Jewish identity looks like in the U.S.. “In America, there is an idea of one way that a Jewish person looks like. I always sort of have to explain who I am. It’s not just understood.”

For Aynalem, Tsion Cafe was bringing to light the diversity of Jews and Israelis to an American audience. “She really was showing what Israel is all about, which is that we are so mixed because we’ve all been in exile in so many different places for so long. She showed that in her restaurant.”

But Aynalem sees the restaurant’s closure as part of a broader trend.“People are quick to say, ‘It’s a Black-owned business, it’s a small business, support it.’ But as long as there’s an intersection with Judaism, there’s no support,” she said. “It raises the question: do you care about Black people, or do you just not care about Jews, regardless of color?”

She added that, as an Ethiopian Jewish woman, she once believed her racial identity shielded her from certain forms of antisemitism.

“For a long time, I felt like that extra layer of being Black almost protected me, because people are scared of being called racist,” she said. “They’re not scared of being called antisemitic.”

In the wake of rising threats and Tsion Cafe’s closure, she said, that sense of insulation has faded.

“It shows you that antisemitism, regardless of what you look like, doesn’t really discriminate,” she said. “I don’t think I have that extra armor anymore. No one is really safe in this climate.”

Aynalem also worries that Ethiopian Jews in America are still understood primarily through the lens of rescue. She said that for many American Jews, the only thing they know about Ethiopian Jews is stories of the dramatic operations that brought them to Israel.

“We’re past that,” she said. “Let’s talk about my generation. We’re part of the culture. People are eating injera, that’s a normal occurrence within Israeli culture now.” For Tali, Tsion Cafe was doing exactly that.

Barhany agrees.

“I always see articles about Ethiopian Jews being rescued,” she said. “I’m kind of fed up with that.” For her, Tsion Cafe was a way to “bring something more positive and more unifying” to the American conversation about Ethiopian Jewish life.

Not just for Ethiopian Jews

Rabbi Mira Rivera of JCC Harlem said Tsion Cafe was woven into the fabric of Jewish life in the neighborhood. “The Ethiopian Jews in Harlem aren’t going anywhere,” she said. “But it was always a joy to have a bastion, a place where you’d say, ‘Let’s meet at Tsion Cafe. Let’s celebrate your birthday there.’ It was part of living in Harlem.”

She compared Tsion Cafe to the Ethiopian Jewish neighborhoods she had visited in Israel, places where a community had a visible center. “This was that place,” she said. “It was where people gathered. Over the years, they changed to vegan and kosher so that the larger Jewish community would start to understand and partake in their culture.” She continued, “to not have that place where all the families can go, it’s really hard.”

But for Barhany, Tsion Cafe was never meant to be “just a cafe.” “I didn’t want it to be a regular cafe where you go in, sit, pay, and go,” she said. “It’s a place where people can nourish and engage in grown-up conversation.”

Amid antisemitic threats, she remains more committed to that mission than ever. Barhany plans to host interfaith gatherings and travel the country to share the flavors and stories of Ethiopian Jewish culture.

“If I can facilitate dialogue, I would be honored,” she said.

“We are not giving up. We are still here. We’re just coming in a different shape or form.”

The post Ethiopian-American Jews lament loss of Harlem restaurant hub appeared first on The Forward.

Uncategorized

Tucker’s Ideas About Jews Come from Darkest Corners of the Internet, Says Huckabee After Combative Interview

US Ambassador to Israel Mike Huckabee looks on during the day he visits the Western Wall, Judaism’s holiest prayer site, in Jerusalem’s Old City, April 18, 2025. Photo: REUTERS/Ronen Zvulun

i24 News – In a combative interview with US Ambassador to Israel Mike Huckabee, right-wing firebrand Tucker Carlson made a host of contentious and often demonstrably false claims that quickly went viral online. Huckabee, who repeatedly challenged the former Fox News star during the interview, subsequently made a long post on X, identifying a pattern of bad-faith arguments, distortions and conspiracies in Carlson’s rhetorical style.

Huckabee pointed out his words were not accorded by Carlson the same degree of attention and curiosity the anchor evinced toward such unsavory characters as “the little Nazi sympathizer Nick Fuentes or the guy who thought Hitler was the good guy and Churchill the bad guy.”

“What I wasn’t anticipating was a lengthy series of questions where he seemed to be insinuating that the Jews of today aren’t really same people as the Jews of the Bible,” Huckabee wrote, adding that Tucker’s obsession with conspiracies regarding the provenance of Ashkenazi Jews obscured the fact that most Israeli Jews were refugees from the Arab and Muslim world.

The idea that Ashkenazi Jews are an Asiatic tribe who invented a false ancestry “gained traction in the 80’s and 90’s with David Duke and other Klansmen and neo-Nazis,” Huckabee wrote. “It has really caught fire in recent years on the Internet and social media, mostly from some of the most overt antisemites and Jew haters you can find.”

Carlson branded Israel “probably the most violent country on earth” and cited the false claim that Israel President Isaac Herzog had visited the infamous island of the late, disgraced sex offender Jeffrey Epstein.

“The current president of Israel, whom I know you know, apparently was at ‘pedo island.’ That’s what it says,” Carlson said, citing a debunked claim made by The Times reporter Gabrielle Weiniger. “Still-living, high-level Israeli officials are directly implicated in Epstein’s life, if not his crimes, so I think you’d be following this.”

Another misleading claim made by Carlson was that there were more Christians in Qatar than in Israel.

Uncategorized

Pezeshkian Says Iran Will Not Bow to Pressure Amid US Nuclear Talks

Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian attends the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) Summit 2025, in Tianjin, China, September 1, 2025. Iran’s Presidential website/WANA (West Asia News Agency)/Handout via REUTERS

Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian said on Saturday that his country would not bow its head to pressure from world powers amid nuclear talks with the United States.

“World powers are lining up to force us to bow our heads… but we will not bow our heads despite all the problems that they are creating for us,” Pezeshkian said in a speech carried live by state TV.