Uncategorized

The treasures discovered by a group of non-Jews in Lublin

דער פּאָעט יעקבֿ גלאַטשטיין, אַ געבוירענער אין לובלין, פּוילן, האָט געשריבן:

לובלין, מײַן הייליקע ייִדישע שטאָט, שטאָט פֿון גרויסן דלות און פֿריילעכע ייִדישע יום־טובֿים…

שטאָט פֿון אויפֿגעוואַכטן קלאַסנקאַמף. . . .

לובלין, מײַן הייליקע ייִדישע שטאָט פֿון בילדונג־דאָרשטיקע יונגע־לײַט און יונגע מיידלעך, פֿון דעם ערשטן בעז־אַראָמאַט פֿון יונג־העברעיִש און פֿון דער באַטעמטקייט פֿון שטאָלצן ייִדיש.

הייליקע שטאָט מײַנע, . . . ווער וועט דיך צוריקשטעלן און צוריקבויען, מײַן הייליקע שטאָט, אַז פֿאַרוויסט ביסטו געוואָרן ביז דײַנע פֿונדאַמענטן און ביסט איין מוראדיקע מצבֿה.

מע שלאָגט שינדלען, מע לייגט דעכער, מען פֿאַרריכט און מען פֿאַרניצעוועט אַן אַלטע פּאַסקודנע וועלט, אָבער מײַן הייליקע שטאָט, די שטאָט פֿון מײַן וועלט, וועט קיין מאָל נישט צוריקגעבויט ווערן.

גלאַטשטיין איז געווען גערעכט. זײַן הייליקע שטאָט לובלין, די שטאָט פֿון אַרום 43,000 ייִדן פֿאַר דעם חורבן, כּמעט אַ דריטל פֿון דער דעמאָלטיקער באַפֿעלקערונג, וועט קיין מאָל נישט צוריקגעבויט ווערן, אָבער עס זײַנען דאָ מענטשן און אַן אָרגאַניזאַציע, דווקא נישט קיין ייִדן און נישט קיין ייִדישע, וואָס אַרבעטן כּדי אויפֿצוהאַלטן דעם אָנדענק פֿון יענער הייליקער ייִדישער שטאָט. די אָרגאַניזאַציע הייסט „בראַמאַ גראָדסקאַ”, (דער שטאָטטויער) און עס געפֿינט זיך אין אַ בנין אין דעם טויער, וואָס ייִדן פֿלעגן רופֿן „גראָדסקע בראָם“ אָדער „ברום“, דורך וועלכן מע פֿלעגט אַרײַנגיין אין דער אַמאָליקער ייִדישע געגנט.

דעם זומער, זײַענדיק אין פּוילן האָבן מיר (מײַן מאַן, אונדזער עלטערע טאָכטער בענאַ און איך) געמאַכט אַן עקסקורסיע קיין לובלין, — די שטאָט וווּ מײַן טאַטע האָט געוווינט ווי אַ צענערלינג ביז 1927, די שטאָט פֿון זײַן אַרײַנטריט אין „אויפֿגעוואַכטן קלאַסן־קאַמף“ און „שטאָלצן ייִדיש“,— און זיך געטראָפֿן מיט פּיאָטער נאַזאַרוקן, אַ געוועזענער ייִדיש־סטודענט פֿון דער ווײַנרײַך־פּראָגראַם בײַם ייִוואָ. פּיאָטער האָט אונדז אַרומגעפֿירט איבער דער שטאָט און דערציילט וועגן דער געשיכטע און אַרבעט פֿון דער אָרגאַניזאַציע.

„בראַמאַ“ האָט זיך אָנגעהויבן אין 1990 ווי אַ טעאַטער־טרופּע אָבער מיט דער צײַט האָבן די באַטייליקטע אײַנגעזען אַז זיי געפֿינען זיך אין האַרץ פֿון עפּעס אַ סך מער דראַמאַטישס ווי די דראַמאַטישיסטע פּיעסע — דער פֿאַרלוירענער ייִדישער וועלט — און זיי האָבן אָנגעווענדט זייערע כּוחות און פֿעיִקייטן אויף רעקאָנסטרוּירן און אויפֿהיטן די געשיכטע פֿון יענער וועלט.

שטעלט זיך די פֿראַגע, פֿאַר וואָס וואָלטן נישט־ייִדן זיך אָפּגעגעבן מיט אויפֿהיטן דעם אָנדערק פֿון די ייִדן? און די פֿראַגע קומט טאַקע דעם גאַסט אַנטקעגן ווען מע טרעט אַרײַן אינעם בנין. אויף דער וואַנט הענגט אַן אויפֿשריפֿט אין דרײַ שפּראַכן: פּויליש, ענגליש און עבריתּ בזה הלשון: „ייִדן וואָס קומען אַהער פֿרעגן אונדז, איר זײַט דאָך נישט קיין ייִדן. איר זײַט פּאָליאַקן און די ייִדישע שטאָט איז ניט אײַער געשיכטע. פּאָליאַקן פֿרעגן אונדז, ,פֿאַר וואָס טוט איר דאָס, איר זײַט דאָך פּאָלאַקן און די ייִדישע שטאָט איז ניט אײַער געשיכטע. אָדער אפֿשר זײַט איר טאַקע ייִדן?

„געדולדיק גיבן מיר צו פֿאַרשטיין אַז דאָס איז אונדזער בשותּפֿותדיקע פּויליש־ייִדישע געשיכטע. צו געדענקען די אויסגעהרגעטע ייִדן דאַרף מען נישט זײַן קיין ייִד.“

אויף אַן אַנדער וואַנטשילד שטייט געשריבן: „עס איז דאָ, בײַם גראָדסקע־טויער, וואָס מע רופֿט אויך ׳דער ייִדישער טויער׳, וואָס איז דער שומר איבער דעם נישט־עקסיסטירנדיקן שטעטל — דעם ייִדישן אַטלאַנטיס — וווּ מיר באַמיִען זיך צו פֿאַרשטיין דעם באַטײַט און דעם שליחות פֿון דעם אָרט הײַנט.“

עס זײַנען דאָ פֿאַרשיידענע אופֿנים און פּראָיעקטן דורך וועלכע זיי טוען דאָס. איינער אַזאַ האָט צו טאָן מיט פֿאָטאָגראַפֿיעס. אין 2015 האָט בראַמאַ גראַדסקאַ באַקומען אַן אוצר, אַ זאַמלונג גלעזערנע נעגאַטיוון (glass plate negatives, בלע״ז) וואָס אַרבעטערס האָבן צופֿעליק געפֿונען אין אַ בוידעם אויף רינעק 4. דער פֿאָרשער יעקבֿ כמיעלעווסקי אין מײַדאַנעק האָט אַנטדעקט אַ מעגלעכע פֿאַרבינדונג צווישן דעם אַדרעס און אַ פֿאָטאָגראַף, אַבראַם זילבערבערג, וואָס האָט דאָרטן אַ שטיק צײַט געוווינט.

די זאַמלונג איז כּולל מער ווי 2,700 גלעזערנע נעגאַטיוון פֿון פֿאַרשיידענע גרייסן, פֿון בילדער גענומען צווישן 1914 און 1939. ניט געקוקט אויף די 75 יאָר, די נישט־גינסטיקע באַדינגונגען אין בוידעם — די קעלט ווינטערצײַט און די היצן זומערצײַט — האָבן ס׳רובֿ פֿון די נעגאַטיוון זיך אויפֿגעהיט. זיי געבן דעם צוקוקער אַ בליק אַרײַן אין דעם וואָס זיי רופֿן „אַ נישט־עקסיסטירנדיקע שטאָט“: בילדער פֿון קינדער און דערוואַקסענע, מענער און פֿרויען, פֿרומע און וועלטלעכע, ייִדן און נישט־ייִדן, פֿאַרשיידענע פֿאַכלײַט, יחידים און גרופּעס, יוגנט־באַוועגונגען און ספּאָרטקלובן.

אַנדערע בילדער פֿון חתונות, בריתן און מצבֿות דאָקומענטירן וויכטיקע מאָמענטן אין דעם ייִדישן משפּחה־לעבן. די פֿאָטאָגראַפֿיעס שפּיגלען אויך אָפּ דעם בהדרגהדיקן איבערגאַנג פֿון אַ פֿרום, טראַדיציאָנעל לעבן צו אַ מער וועלטלעכן. דאָס רובֿ זײַנען בילדער פֿון פּשוטע לײַט, אין גאַנג פֿון דער טאָג־טעגלעכקייט — מענטשן וואָס האָבן קיין מאָל נישט געמיינט אַז זיי וועלן ווערן שטומע עדות אויף אַ פֿאַרשוווּנדענער וועלט.

אַן אַנדער פּראָיעקט האָט צו טאָן מיט דער דיגיטאַלער ביבליאָטעק פֿון דער ישיבֿת חכמי לובלין, אַ וויכטיקער מקום־תּורה וואָס האָט זיך געעפֿנט אין לובלין אין 1930, און איז געווען רעוואָלוציאָנער אין דער ישיבֿה־וועלט, נישט נאָר פֿאַר דעם דף־יומי וואָס איר פֿאַרלייגער, ר’ מאיר שאַפּיראָ, האָט אײַנגעפֿירט אויף אַ קאָנפֿערענץ פֿון אַגודת־ישׂראל אין ווין אין 1923, נאָר אויך פֿאַר איר שיינעם בנין וואָס האָט געהאַט אַן עסזאַל און אינטערנאַטן פֿאַר די בחורים, אַ סגולה צו די שוועריקייטן פֿון דינגען אַ צימער און עסן טעג אין פֿרעמדע הײַזער.

במשך פֿון די קנאַפּע צען יאָר פֿון איר עקסיסטענץ, פֿון 1930־1939, האָט די ישיבֿה אָנגעזאַמלט אַ ביבליאָטעק פֿון צענדליקער טויזנט ספֿרים, ביכער און צײַטשריפֿטן. אין 1941 האָבן די נאַציס אײַנגענומען לובלין און ביז מיט אַ יאָרצענדליק צוריק האָט מען געמיינט אַז נאָר פֿינעף ביכער האָבן זיך געראַטעוועט. אָבער אַ דאַנק דער איבערגעגעבענער אַרבעט פֿון בראַמאַ גראָדסקאַ, אונטער דער אָנפֿירערשאַפֿט פֿון פּיאָטער נאַזאַרוק און מאָניקאַ טאַרײַקאָ, האָבן זיך שוין אָפּגעזוכט ביז הײַנט 1,555 ביכער, פֿונאַנדערגעשפּרייט אין ביבליאָטעקן איבער דער גאָרער וועלט.

בראַמאַ גראָדסקאַ ווייסט אַז ס׳איז נישטאָ קיין שׂכל אין צוריקברענגען די ביכער קיין לובלין, אַ שטאָט וואָס האָט קוים אַ מנין ייִדן. דערפֿאַר צילעווען זיי מיט זייער דיגיטאַלער ביבליאָטעק אויסצוזוכן, אידענטיפֿיצירן און קאַטאַלאָגירן אַלע ביכער מיט שטעמפּלען פֿון דער ישיבֿה. אַזוי האָפֿן זיי צו רעסטאַוורירן די זאַמלונג און זי כאָטש סימבאָליש צוריקקערן קיין לובלין.

אַזוי ווי בראַמאַ גראָדסקאַ דינט ווי דער אַדרעס פֿאַר אויפֿהיטן דעם אָנדענק פֿון די ייִדן אין לובלין קען מען דאָרטן געפֿינען אויסטערלישע זאַכן וואָס מענטשן האָבן צופֿעליק געפֿונען און אַהין אַרײַנגעגעבראַכט: למשל, אַ וואָגנראָד וואָס האָט זיך ערגעץ געוואַלגערט, געמאַכט פֿון אַ ייִדישער מצבֿה, אַן עדות אויף אַנטיסעמיטישן וואַנדאַליזם.

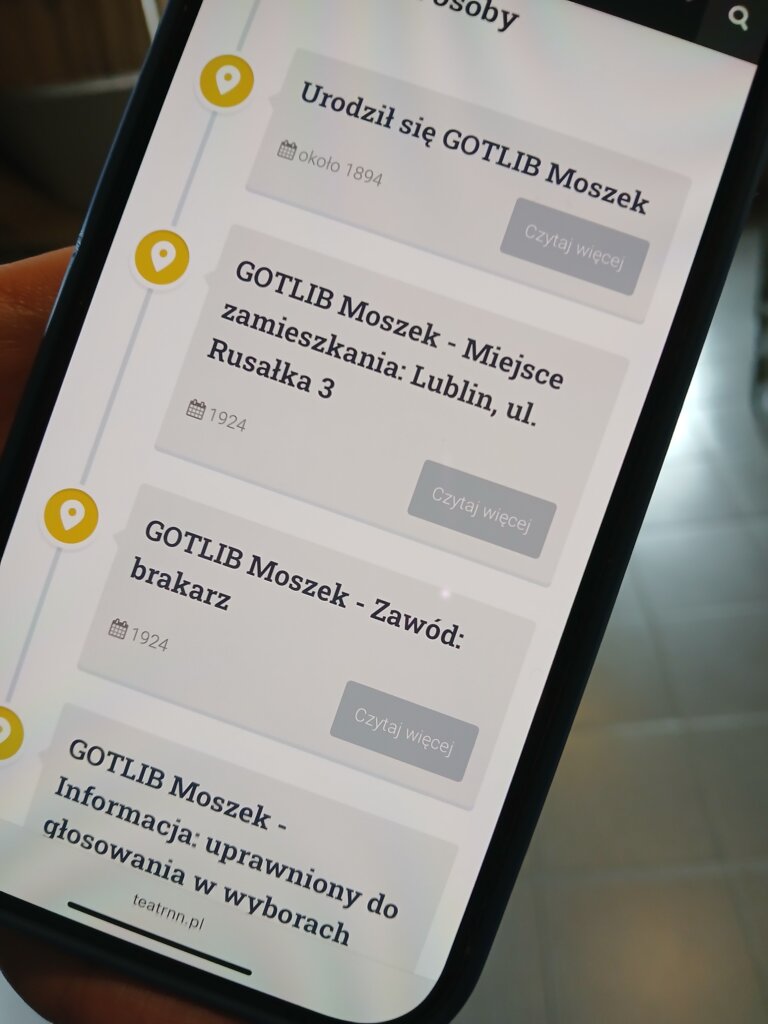

בראַמאַ פֿירט אויך אָן מיט דערציִערישע פּראָגראַמען וועגן דעם חורבן און דעם ייִדישן לעבן פֿאַר דעם חורבן פֿאַר לערערס פֿון פּוילן און פֿון אויסלאַנד. זיי האָבן אַ דאַטן־באַזע וווּ זיי זאַמלען אינפֿאָרמאַציע וועגן געוועזענע לובלינער פֿון פֿאַרשיידענע מקורים, ווי למשל, רשימות פֿון אײַנוווינערס פֿון בנינים און שטים־רשימות.

איך האָב, פֿאַרשטייט זיך, געבעטן בײַ פּיאָטערן ער זאָל זוכן אינפֿאָרמאַציע וועגן מײַנע אייגענע אָבֿות, דער משפּחה צוקער. האָט ער געזוכט אונטער זייער אַדרעס, רוסאַלקע 3, וווּ ער האָט אונדז פֿריִער געהאַט געפֿירט. צווישן די אַלע נעמען פֿון די אײַנוווינערס פֿון בנין וואָס האָבן זיך געפֿונען אין דער דאַטן־באַזע, בתוכם נישט קיין איין צוקער (מסתּמא ווײַל די משפּחה איז שוין געהאַט אַוועק פֿון לובלין אין די סוף צוואַנציקער יאָרן) האָט איין נאָמען מיר פֿאַרכאַפּט דעם אָטעם: מאָשעק (משה) גאָטליב, פֿון פֿאַך אַ בראַקער.

איך האָב קיין מאָל נישט געטראָפֿן משה גאָטליבן. געוווּסט האָב איך נאָר אַז ער איז געווען דער ערטשער מאַן פֿון דעם טאַטנס עלטסטער שוועסטער לובע און אַז זיי האָבן נאָך אַ פּאָר יאָר זיך געגט. כאָטש די מומע לובע איז שוין געווען אַ בונדיסטקע האָט זי מסכּים געווען צו אַ שידוך (איך ווייס ניט צי פֿרײַוויליק צי נישט) מיטן זון פֿון איינעם אַ גאָטליב מיט וועמען דער טאַטע (מײַן זיידע), אויך אַ בראַקער, האָט געהאַט געשעפֿטן.

מיר איז דאָס אַלע מאָל געווען אַזאַ אינטערעסאַנטער באַווײַז פֿון דעם וואָס ווי די אַלטע וועלט און די נײַע זײַנען דעמאָלט געווען געקניפּט און געבונדן. נאָך אַלעמען, ווי קומט אַ בונדיסטקע צו אַ שידוך?! מער ווי דאָס האָב איך וועגן משה גאָטליבן נישט געוווּסט. ס׳איז מיר קיין מאָל אַפֿילו נישט אײַנגעפֿאַלן צו פֿרעגן אויב ער איז אומגעקומען אָדער האָט איבערגעלעבט דעם חורבן; בײַ מיר האָט זײַן שייכות צו מײַן משפּחה זיך געענדיקט מיטן גט ערגעץ אין די 20ער יאָרן. נאָר ס׳איז קלאָר אַז ער איז אומגעקומען.

איך האָב געקענט זייער זון איצוש ע״ה, וואָס האָט אין די 1950ער יאָרן עמיגרירט קיין קאַנאַדע, וווּ מיר האָבן געוווינט, נאָר ס׳איז מיר אויך קיין מאָל נישט אײַנגעפֿאַלן אים צו פֿרעגן וואָס איז געשען מיטן טאַטן זײַנעם. צי האָט ער נאָך אַ מאָל חתונה געהאַט, האָט ער געהאַט אַנדערע קינדער — האַלבע־ברידער אָדער ־שוועסטער? זײַנען זיי אויך אומגעקומען?

מסתּמא וועל איך קיין מאָל נישט האָבן קיין ענטפֿער אויף די פֿראַגעס אָבער די קנאַפּע ידיעות האָבן אויפֿגעלעבט פֿאַר מיר אויף אַ פּאָר מינוט אַ מענטשן. דאָס איז טאַקע דער ציל פֿון בראַמאַ גראָדסקאַ — צו ווײַזן אַז די אומגעקומענע זײַנען נישט געווען בלויז ציפֿערן. דאָס ביסל אינפֿאָרמאַציע וועגן משה גאָטליבן איז אַרײַן אין איינער פֿון די 43,000 פּאַפּקעס — איין פּאַפּקע פֿאַר יעדן אומגעקומענעם ייִד, וואָס האָט געוווינט אין לובלין ערבֿ דעם אויסבראָך פֿון דער מלחמה.

און דווקא יענע דינע פּאַפּקעס האָבן מער פֿון אַלע פּראָיעקטן און חפֿצים, געמאַכט אויף מיר דעם גרעסטן אײַנדרוק. בראַמאַ צילעוועט צו געפֿינען עפּעס אַ ידיעה וועגן יעדן פֿון די 43,000 קדושים. עס קען זײַן אַ נאָמען, אַן אַדרעס, אַ פֿאַך, אַ געבוירן־טאָג, עפּעס וואָס ראַטעוועט דעם נאָמען פֿון אַנאָנימקייט און אָטעמט אַרײַן אין אים אַ נשמה.

וועגן 35,000 פֿון די אַמאָליקע אײַנוווינער האָט מען שוין עפּעס אַנטדעקט. געבליבן זײַנען נאָך 8,000 נשמות וואָס וואַרטן אויף אַ תּיקון.

The post The treasures discovered by a group of non-Jews in Lublin appeared first on The Forward.

Uncategorized

‘This isn’t the Gov. Newsom that we know’: One week after apartheid remark, calls to reconsider remain unheeded

One week after California Gov. Gavin Newsom caused a stir by using the term “apartheid” to describe Israel, Jewish leaders in the state and beyond — have tried in vain to get him to walk back his statement.

Those seeking answers include allies of the term-limited governor, a likely presidential candidate, who have defended his record and even the comment itself.

Newsom said March 3 on a podcast that Israel had been talked about “appropriately as sort of an apartheid state,” and suggested that a time may come when the U.S. should reconsider its military aid to Israel.

Some Jewish leaders have said the apartheid comment had been taken out of context, and representatives of Jewish groups who met with the governor’s staff following Newsom’s remark called the conversation constructive. But Newsom has not backtracked in public appearances since then, leaving those leaders split on whether a serious contender for the 2028 Democratic nomination — long seen as a champion of Jewish causes — is plotting a new course on the national stage.

Newsom’s clarification two days later — noting that he was referencing a Thomas Friedman column in the New York Times about the direction Israel was headed — offered them little succor.

“It’s out of step,” said David Bocarsly, executive director of Jewish California, a group that represents more than 30 Jewish community organizations in the state. “This isn’t the Governor Newsom that we know.”

Newsom’s office did not respond to an inquiry.

‘Sort of an apartheid state’

Newsom made the remark in a live taping of Pod Save America, a podcast hosted by former Obama administration staffers Jon Favreau and Tommy Vietor. The duo, who are among the Democratic mainstream’s most vocal Israel critics, asked Newsom whether he thought the time had come to reevaluate American military support for the country.

In an extended response, Newsom brought up Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

“The issue of Bibi is interesting, because he’s got his own domestic issues,” Newsom said. “He’s trying to stay out of jail. He’s got an election coming up. He’s potentially on the ropes. He’s got folks, the hard line, that want to annex the West—the West Bank. I mean, Friedman and others are talking about it appropriately as a sort of an apartheid state.”

As to whether the United States should consider rethinking military support for Israel down the road, Newsom replied, “I don’t think you have a choice but that consideration.”

Newsom’s use of the term and apparent willingness to break from pro-Israel orthodoxy sent heads spinning. Jewish Insider described the interview as a “hard left” shift. A column in the Jewish Journal of Greater Los Angeles assailed Newsom for “finger in the wind politics.” And secular outlets like Politico and The Guardian reported that Newsom had likened Israel to an apartheid state.

Even organizations that have historically enjoyed a collaborative relationship with Newsom publicly condemned the remarks. Jewish California, whose member groups include the state’s local Jewish federations, took to Instagram to call them “inflammatory.”

Newsom said in a subsequent live appearance March 5 that he was referencing Friedman’s recent assertion that Israel annexing the West Bank without giving Palestinians equal rights would create an apartheid system.

“I was specifically referring to a Tom Friedman column last week, where Tom used that word, ‘apartheid,’ as it relates to the direction Bibi is going, particularly on the annexation of the West Bank,” he said. “I’m very angry with what he is doing.”

The clarification wasn’t strong enough for the Jewish California coalition. Bocarsly told The Jewish News of Northern California last week the groups hoped to see a definitive public statement from the governor that he continues to support funding for Israel’s defense and that he “doesn’t believe that a thriving, pluralistic and democratic society, as it is in its current state, is an apartheid state.”

Tye Gregory, chief executive of the JCRC Bay Area — a Jewish California member group — added to the outlet that “we need to hear directly from the governor.”

The coalition left its conversation with Newsom officials believing such a statement was forthcoming, but Bocarsly said his optimism was fading.

“It’s been several days, and we haven’t seen the clarification that we had hoped,” Bocarsly said. “And we’re still waiting.”

A loaded word

Some international and Israeli human rights organizations say Israel’s occupation of the West Bank and the treatment of Palestinians in the territory already constitutes apartheid.

The term was originally used to describe the system of institutionalized segregation in South Africa that granted the minority white population official higher status, denied nonwhites the right to vote and enforced a range of other forms of economic, political and social domination. Those applying the apartheid term to Israel point to the Israeli citizenship, voting rights, freedom of movement and legal protections granted in the West Bank to Israeli residents but not Palestinians in the territory.

But many Jews say that any charge of apartheid — whether referring to the present or a hypothetical future — oversimplifies the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and is used as a cudgel to delegitimize the Jewish state, where within its boundaries Israeli Arabs can vote and travel freely.

Israel annexing the West Bank — a stated goal of far-right ministers in the Netanyahu coalition like Itamar Ben Gvir and Bezalel Smotrich — would replace the premise of Palestinian sovereignty in the territory, which is officially governed by the Palestinian Authority, and enshrine the two-tier system. Such a step, Friedman wrote in a Feb. 17 column, would amount to apartheid.

“It’s been several days, and we haven’t seen the clarification that we had hoped. And we’re still waiting.”

David BocarslyExecutive Director, Jewish California

Bocarsly believed that Newsom’s reference to apartheid had been misinterpreted — even after the governor clarified his views — as describing Israel today, rather than a future scenario.

Nevertheless, he said, by invoking the term “apartheid” at all the governor had played into an effort among Israel’s detractors to make use of terms like “apartheid” and “genocide” to describe the Jewish state’s actions a litmus test for elected leaders.

Only a month earlier, Democratic State Senator Scott Wiener — then the co-chair of California Legislative Jewish Caucus — called Israel’s war in Gaza a genocide, after first declining to during a congressional candidate debate and getting jeers in response.

“For someone as close to our community as Gavin Newsom is, I think it was disappointing and painful for a lot of people to see that he was falling into this test,” Bocarsly said. “We want to know that when it comes down to it, that he is willing to avoid criticizing Israel in that way.”

Halie Soifer, chief executive of the Jewish Democratic Council of America, said Newsom’s initial comments had been taken out of context, and she was satisfied with his later clarification. Instead, she objected more to Newsom’s suggestion that the U.S. might eventually withhold military aid to Israel. The JDCA rejects withholding or conditioning such aid in its platform.

Still, while the “apartheid” phrase got the most attention, Soifer suggested it was just as revealing when — in the same podcast appearance — Newsom had described Israel’s rightward turn under Netanyahu as “heartbreaking.”

“It’s indicating his emotions are actually in this but also disagreement with the policies of the current Israeli government,” Soifer said. “And that is a view that polling has consistently shown is held by the vast majority of American Jewish voters.”

But she acknowledged that further backtracking would help, noting that she had listened to the section of the podcast multiple times to get a clear idea of his intent.

“I don’t think the average person is doing that,” Soifer said in an interview, “and he shouldn’t assume that either.”

The governor you know

The comments seemed to break with Newsom’s track record of verbal and legislative support for Jewish life both in the state and in Israel.

During his seven years in the governor’s office, he has funded the largest nonprofit security grant program in the nation, signed a landmark bill aimed at addressing antisemitism in public education and poured some $50 million into Holocaust survivor assistance programs. He also visited Israel to meet with Oct. 7 survivors less than two weeks after the attacks.

That made Newsom’s failure to hedge in a more fulsome way all the more confounding for his Jewish allies.

Gregg Solkovits, president of Democrats for Israel Los Angeles, a Democratic party club, thought the governor had been intentionally vague — and was intentionally waiting out the Jewish criticism — to “protect his left flank” as a future presidential candidate.

“He knows that in the upcoming election, there will be Bernie-supportive candidates who are going to be running for the nomination, and he will be attacked for being too pro-Israel, which he has been consistently,” Solkovits said. “Would I wish that he had not taken that approach entirely? Of course. I also understand he’s running for president.”

Soifer offered that Newsom might just be waiting for the right opportunity.

“He doesn’t actually legislate on this particular issue, so perhaps he feels he doesn’t need to clarify,” she said. “But I think it would be helpful for him to clarify that, especially if he’s seeking an opportunity at some point in the future to weigh in on such decisions.”

The post ‘This isn’t the Gov. Newsom that we know’: One week after apartheid remark, calls to reconsider remain unheeded appeared first on The Forward.

Uncategorized

Norway Police Apprehend 3 Suspects in US Embassy Bombing

Police vehicles outside the US embassy, after a loud bang was reported at the site, in Oslo, Norway, March 8, 2026. Photo: Javad Parsa/NTB/via REUTERS

Norwegian police said on Wednesday they had apprehended three brothers suspected of carrying out Sunday’s bombing at the US embassy in Oslo, in an attack investigators have branded an act of terrorism.

The powerful early-morning blast from an improvised explosive device (IED) damaged the entrance to the embassy‘s consular section but caused no injuries, Norwegian authorities have said.

The three suspects, all in their 20s, are Norwegian citizens with a family background from Iraq, police said.

“They are suspected of a terror bombing,” Police Attorney Christian Hatlo told reporters.

“We believe they detonated a powerful bomb at the U.S. embassy with the intention of taking lives or causing significant damage,” Hatlo said, adding that none of the suspects had so far been interrogated.

One of the men was believed to have planted the bomb while the two others were believed to have taken part in the plot, Hatlo said.

The brothers, who were not named, had not previously been subject to police investigations, he added.

A lawyer representing one of the three men said he had only briefly met with his client and that it was too early to say how the suspect would plead.

Lawyers representing the two others did not immediately respond to requests for comment when contacted by Reuters.

“Although it is early in the investigation, it is important that the police have achieved what they characterize as a breakthrough in the case,” Norway‘s Minister of Justice and Public Security Astri Aas-Hansen said in a statement.

Images of one of the suspects released by police on Monday showed a hooded person, whose face was not visible, wearing dark clothes and carrying a bag or rucksack.

Investigators on Monday said one hypothesis was that the incident was “an act of terrorism” linked to the war in the Middle East, but that other possible motives were also being explored.

Police are now investigating whether the bombing was done on behalf of a foreign state, Hatlo said, reiterating that they were also looking into other possible motives.

Europe has been on alert for possible attacks as the US and Israel conduct air strikes on Iran and Iran strikes Israel and US targets in the Middle East.

On Monday, a synagogue in the Belgian city of Liege was damaged by a blast that authorities called an antisemitic attack. It was not clear who was behind it.

Uncategorized

Belgium’s Jewish Community Sounds Alarm on Rising Antisemitism After Liège Synagogue Attack

Police secure the site of a synagogue damaged by an explosion early on Monday, in Liege, Belgium, March 9, 2026. Photo: REUTERS/Yves Herman

Just days after a synagogue in Liège, Belgium was struck in an apparent antisemitic bombing, the local Jewish community is sounding the alarm over a surge in hostility and targeted violence against Jews across the country.

In an interview with the local news outlet La Première on Tuesday, the president of the Committee of Jewish Organizations in Belgium (CCOJB), Yves Oschinsky, called on government authorities to deploy soldiers to protect Jewish sites and institutions if police protection proves insufficient.

Following the attack on a synagogue in Liège, a city in the country’s eastern region, early Monday morning, Oschinsky warned that the Jewish community faces a far greater threat than authorities publicly acknowledge, emphasizing that Jewish institutions remain at heightened risk.

He also slammed the government for failing to appoint a national coordinator to fight antisemitism, while urging political parties and officials to take urgent, concrete action to protect the Jewish community.

Like most countries across the Western world, Belgium has seen a rise in antisemitic incidents over the last two years, in the wake of the Hamas-led invasion of and massacre across southern Israel on Oct. 7, 2023.

According to the Belgian Interfederal Center for Equal Opportunities and the Fight against Racism and Discrimination (Unia), which tracks antisemitism nationwide, 192 reports of antisemitism and Holocaust denial were filed in 2025, following a record 270 cases in 2024 — marking two consecutive years well previous years.

Before the Oct. 7 atrocities, only 31 antisemitic cases had been reported in Belgium in 2022.

On Tuesday, the Brussels-based Jonathas Institute released a new report warning that antisemitic prejudices remain widespread and deeply entrenched in Belgium.

“The results are clear: the study highlights that the population of Brussels continues to hold many antisemitic stereotypes ‘inherited from the past’ of a religious or political nature,” the institute said in a statement.

The newly released report found that 40 percent of respondents in Brussels agreed with the claim that Jews control the financial and banking sectors, while one in four blamed Jews for various economic crises.

According to the study, these stereotypes are “sometimes expressed as obvious truths” without overt hostility, a pattern the report warns makes them especially prone to being trivialized, particularly online.

More than one in five Belgians believe Jews are “not Belgians like the others,” while 21 percent label Jews an “unassimilable race.”

“The attack on the synagogue in Liège confirms that it is no longer just antisemitic speech that has been unleashed, but antisemitic acts as well. This aggressive antisemitism continues to rise,” the institute said.

The survey also found that 70 percent of respondents believe Jews form a “close-knit or closed community.”

In relation to the war in Gaza, 39 percent of Belgians claim that “Jews are doing to Palestinians what the Nazis did to them.” This view is particularly common among 18- to 35-year-olds, who are more likely to compare Israel’s actions to those of the Nazis.

Within far-right circles, 69 percent believe Jews exploit the Holocaust, while 72 percent say Jews use antisemitism for their own interests.

Based on these findings, the Jonathas Institute urged authorities and policymakers to strengthen historical education, improve digital literacy, and remain vigilant against narratives that normalize or justify hostility toward Jews, warning that such discourse can ultimately spark real-world violence.

The institute also calls for formalizing the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance’s (IHRA) working definition of antisemitism, aiming to better distinguish “legitimate criticism of Israel” from “forms of anti-Zionism that revive antisemitic patterns.”

IHRA — an intergovernmental organization comprising dozens of countries including the US and Israel — adopted the “working definition” of antisemitism in 2016. Since then, the definition has been widely accepted by Jewish groups and lawmakers across the political spectrum, and it is now used by hundreds of governing institutions, including the US State Department, European Union, and United Nations.

According to the definition, antisemitism “is a certain perception of Jews, which may be expressed as hatred toward Jews. Rhetorical and physical manifestations of antisemitism are directed toward Jewish or non-Jewish individuals and/or their property, toward Jewish community institutions and religious facilities.” It provides 11 specific, contemporary examples of antisemitism in public life, the media, schools, the workplace, and in the religious sphere. Beyond classic antisemitic behavior associated with the likes of the medieval period and Nazi Germany, the examples include denial of the Holocaust and newer forms of antisemitism targeting Israel such as demonizing the Jewish state, denying its right to exist, and holding it to standards not expected of any other democratic state.