RSS

My family’s 1948 Israeli trauma has me torn between anger and compassion right now

(JTA) — The projectile landed when the kids were playing in the courtyard.

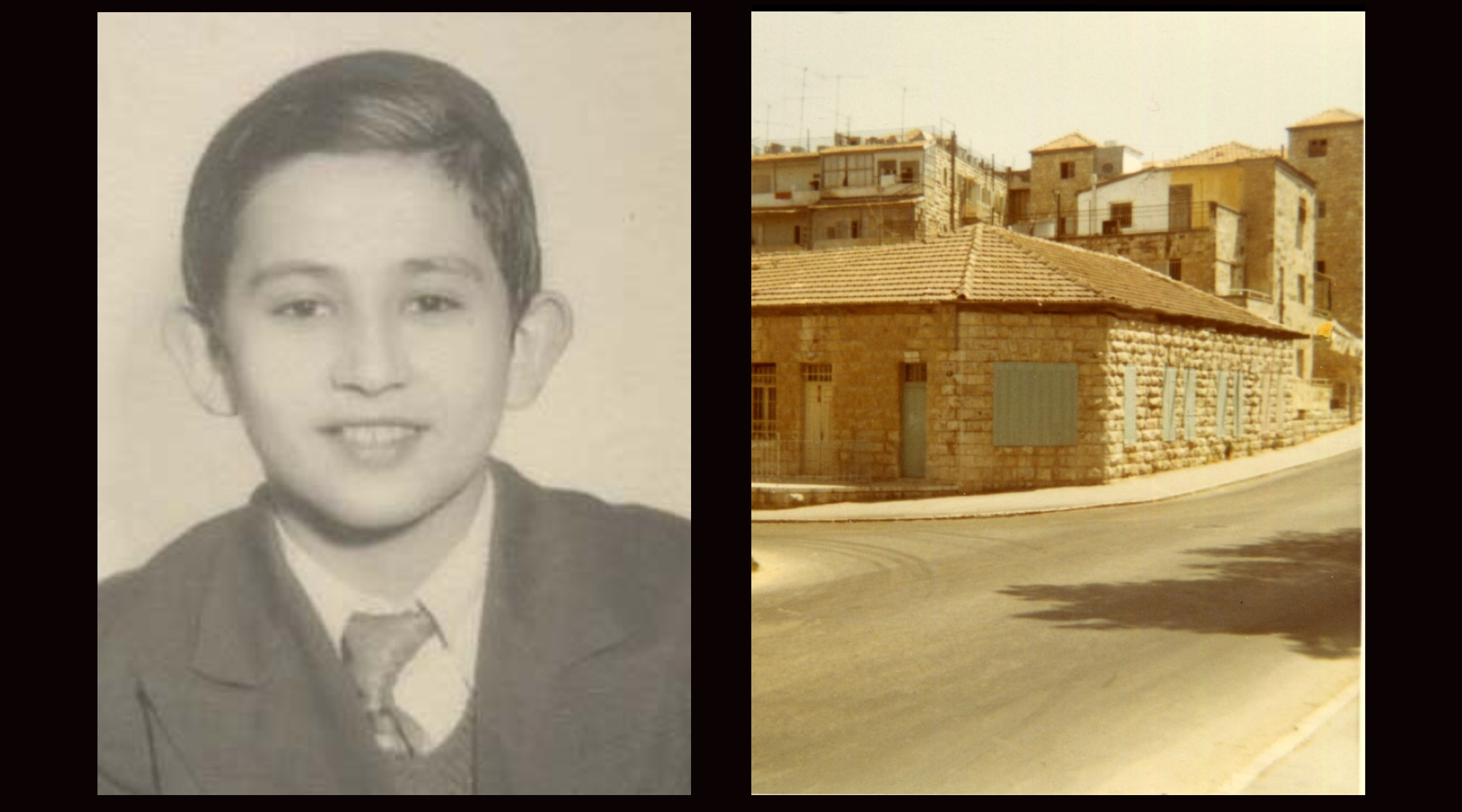

Well, most of the kids. The 9-year-old was watching from the porch of the ramshackle Jerusalem home, tentative but curious. Suddenly he saw them stop playing.

His older brother fell first. A second later his younger sister dropped. And then his mother was on the ground.

The boy ran down the porch steps. The brother and sister were nearly motionless, blood leeching out. He prodded them — nothing. But his mother was alive. He could see her writhing, grabbing her leg, and he could see the giant metallic fragments protruding from it. “Ezra, ezra,” the boy screamed in Hebrew, “help, help.” But this was a back-alley in a poor neighborhood. No one was rushing to help.

The time was June 1948. The conflict in which the shell was lobbed — from just outside the courtyard — was the first Israeli Arab War. And the boy was my father.

His brother and sister were dead before the paramedics could arrive. But his mother was alive. Sort of. Just two months later, she would die in a Jerusalem hospital from all that lodged shrapnel — on the day before Tisha B’Av, the national Jewish day of mourning. All tragedies come at strange times, but this was the strangest. Every Jew in Jerusalem that summer was experiencing the ecstasy of a new state, the fulfillment of a 2,000-year-old dream. My father was experiencing becoming an orphan.

And my grandfather, off at his milk-delivery job when the attack happened, was experiencing overwhelming uncertainty, widowhood, single-fatherhood. As a teenager two decades earlier he had fled to Mandatory Palestine to escape pogrom-filled White Russia, hoping to avoid the antisemitic violence befalling everyone around him. Now here he was, just one more victim of it. The setting changes. The pain, he might say (if he could ever bring himself to talk about it), stays the same.

Three other siblings survived the attack — my father’s 4-year-old sister and 12-year-old brother, both wounded while playing in the courtyard, along with a baby sleeping inside.

All of them had their existence turned upside down — shaken and deposited at the side of life’s road by an event whose causes they barely understood and whose consequences they couldn’t begin to grip. But the 9-year-old suffered in the unique way 9-year-olds suffer, old enough to register but too young to fathom. He didn’t know he’d never be the same. He just wondered if he could ever again be anything.

More than 50 people were killed and 88 wounded in a blast in the Jewish section of Jerusalem, Feb. 22, 1948. (Bettmann Archive/Getty Images)

We were sitting in his Brooklyn apartment recently watching the news — I and my father, now 84 and long a naturalized middle-class American, the accent and most visible traces of his Israeli roots scrubbed away. He had arrived in this country with what remained of his family two years after the attack and tried to put it behind him. Like trying to put the backseat of the car behind you.

“Thousands of wounded, alive but carrying with them the bullet holes and the shrapnel wounds and the memory of what they endured,” President Biden was saying from the TV about the Oct 7 attacks. I stole a sidelong glance at my father; I didn’t need to see the tears welling up in his eyes to know they were there.

“You all know these traumas never go away,” Biden finished from the screen.

In all the decades I’ve known my father, the memory of that day has never been more than a minute’s distance from his consciousness. How could it? Like an at-ease soldier, it lingers just out of frame, waiting for the order to snap to attention and make a march on your soul.

But this time was different. As the Internet and television overflowed with images of blood-soaked cribs, children stolen from their homes, parents burned to death in their safe rooms, grandparents executed on their front lawns, his mind appeared to be filling with a new kind of horror.

This wasn’t the abstraction of Israeli soldiers slain in war or even the vivid images of Jewish civilians dying in terrorist attacks on buses, as they did in droves in the second intifada of the early 2000’s. This was people murdered by terrorists in the one place they were sure violence would never visit — their own homes.

A home on Kibbutz Kfar Aza, reduced to rubble on Oct. 7, is seen one month after Hamas’ attack on Israel. (Deborah Danan)

When my father goes online to see young Israelis watching their parents die in front of them — or to hear of the trauma the recently released 9-year-old Irish-Israeli hostage Emily Hand has been experiencing — he isn’t just absorbing the general pain of human suffering. He is watching a YouTube video of his own past.

And so, in a sense, am I. As someone who was told this story from the earliest age – who still tearfully recalls my father taking me, as a 9-year-old boy myself, to the courtyard in Jerusalem where everything happened so he could describe it in whispered tones — I’ve eternally been under the toxic spell of that June 1948 day. Angry thoughts would sometimes follow me, and I would stew with retributive feelings. These were faceless devils come to steal our lives. And they deserved a devil’s fate in return.

I carried feelings of that day with me into a post-high school gap year in Israel, as a frequent returnee to the country to see friends and family, and even as a journalist occasionally doing stories from the Middle East. Carried it with me as trauma; carried it with me as a source of so many ambivalences.

My internalization of that tragic day is in a tug, constantly, with the progressive views I hold elsewhere. I chose to do that gap year at a politically left-leaning school – in the West Bank. I became a solid two-stater and Yitzhak Rabin acolyte who nonetheless could feel an ineffable comfort when hearing family talk hawkishly about jihadism and the remedies it requires.

I hear cable-news pundits speculate about the conflict’s root causes, and am filled with ire and victimhood; what do root causes have to do with your family being killed in their own home? What possible rights can these armchair people — who will never experience a minute of political violence in their lives – possibly hold that allows them to tell me how to feel, to make so much empty noise? Rancor is the privilege of the unaffected.

And then I go the opposite way. I watch the bombardment of Gaza and I am drawn inexorably to the parallels; that Palestinian boy in the photograph losing a parent is not at all different from him. I hear a rabbi preach about the Jewish respect for sanctity of life and wonder how the young Gazan doppelganger would feel about that statement. It can make me double down on grievance, but my family’s history also makes me attuned to political suffering broadly; my grasp of what an enemy’s violence can do to you equips my radar to detect what my side’s violence has done to them.

A boy plays in the rubble of destroyed houses and buildings in Rafah in the southern Gaza Strip on Dec. 18, 2023. (Mohammed Abed/AFP via Getty Images)

Knowing that so much of my family has drowned in this infinity pool of violence has a paradoxical effect: It makes me at once more angry on behalf of my people and more sympathetic to those arrayed against them.

“I am too progressive for the Zionists and too Zionist for the progressives,” I tell a close confidante, and she hears and smiles sympathetically. Perhaps that is my place, tilted between trauma and empathy. Perhaps that is the curse of the survivor’s son. You are destined to live in the lonely middle — haunted by everything, aligned with no one.

My father, on the other hand, can live unburdened by such complexities, a firsthand victim free to dig into the anger and pain.

And he does. As we watch the news he tells me plaintively of the Jewish suffering he sees, stopping himself not because he doesn’t want to finish but because he can’t, tears choking away what’s left of his dispassion. All of these Jewish survivors are him, and he knows with a prophet’s clarity what awaits them in the lost and wandering years ahead. I listen to him and say nothing, hoping in the silence there is comfort.

A militancy is animating him — to aggressively attack Hamas until every last hint of a threat is wiped off the earth. He doesn’t shout it from the rooftops, and he doesn’t explicate it in detail. But his emotions are clear every time his eyes get puffy and in all the moments his voice drops to a hush, every night and every morning since the weekend of Oct. 7, no end in sight. The Israeli army needs to entrench themselves in Gaza, or Lebanon, or Iran, or anywhere else they need to go to decisively wipe out anyone who had a hand in this, who could ever have a hand in something like this.

His anger isn’t revenge. It isn’t even anger in the way any human, invoking ethnic pride or historical specters, might feel anger. His anger is of the most personal sort — of the most personal mission.

I might disagree with his hawkishness or lack of pragmatism. But how could I ever judge it? It comes from a place of bottomless hurt, of wanting to do anything possible to reverse that hurt for him. And if not for him, then for the next him – for all the Jews who have not yet known his pain, and who should never know his pain. If his mother died for anything, it is this: to prevent future mothers from dying.

It is his deeply understandable impulse that makes me sad – not for my father but for a region. Because it is this deeply understandable impulse that will ensure the violence never stops; it is this deeply understandable impulse that is the reason the problem may never be solved.

Not inept, corrupt, self-interested leaders, though those don’t help. Not depraved terrorists or zealous ideologies, though those always make things worse. No, it might never stop because of all the people who make the work of those types possible — who give them both incentive and means.

Because of all of those with bottomless hurt, with deep grievance, with a hawkishness I could never judge. So many of them, over a period of 75 years, on so many religious and political and ethnic sides. So many more being created on every single one of these dark days.

A woman wounded in the bombing of the Jewish Agency building in Jerusalem is ferried to a hospital, March 15, 1948. (Getty Images Archive)

Every time I hear about a civilian killed I don’t see one more number ticking up on some kind of military or moral odometer. I see that person’s children, and all of their children’s children, now themselves laden with irremediable grievance — with a reason to encourage violence that surely, this time, will prevent future violence. I see clusters of permanently tormented survivors, multiplying and metastasizing like some kind of biology educational video, and soon I can no longer count each one or apprehend their number. I see my father, and me.

The conflict may play out with weapons and rhetoric, on a board of land and geopolitics. But it is powered by people who feel they have lost something. And these losses, by definition, can never be diminished; these losses, by their very painful nature, continue to pile on top of each other until there is no longer just a mass of traumatized people like my father, crying in their apartments, but entire cities of them, shouting to the heavens, and to their leaders.

You would think feeling referred pain from a victimized father would make a person less understanding of an enemy’s experience. And sometimes it does; I’d be lying if I said in the past two months I haven’t had flashbacks to those childhood revenge fantasies. But then I remember the thousands of people like my father multiplying everywhere, and I go the other way. Toward carrying the trauma of my people, but because of that trauma also feeling empathy for the other. The lonely middle, alienating as it is, is large and accommodating.

In the face of this, all I could do is to keep broadcasting the pain of my father and his kind, to tell the stories of all those people who have lost and don’t deserve to lose anymore, in the hope it finally slows down the grisly momentum.

In the hope no son ever again has to sit watching the news with his father and know, without looking, the tears welling up in his eyes.

—

The post My family’s 1948 Israeli trauma has me torn between anger and compassion right now appeared first on Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

RSS

After False Dawns, Gazans Hope Trump Will Force End to Two-Year-Old War

Palestinians walk past a residential building destroyed in previous Israeli strikes, after Hamas agreed to release hostages and accept some other terms in a US plan to end the war, in Nuseirat, central Gaza Strip October 4, 2025. Photo: REUTERS/Mahmoud Issa

Exhausted Palestinians in Gaza clung to hopes on Saturday that US President Donald Trump would keep up pressure on Israel to end a two-year-old war that has killed tens of thousands and displaced the entire population of more than two million.

Hamas’ declaration that it was ready to hand over hostages and accept some terms of Trump’s plan to end the conflict while calling for more talks on several key issues was greeted with relief in the enclave, where most homes are now in ruins.

“It’s happy news, it saves those who are still alive,” said 32-year-old Saoud Qarneyta, reacting to Hamas’ response and Trump’s intervention. “This is enough. Houses have been damaged, everything has been damaged, what is left? Nothing.”

GAZAN RESIDENT HOPES ‘WE WILL BE DONE WITH WARS’

Ismail Zayda, 40, a father of three, displaced from a suburb in northern Gaza City where Israel launched a full-scale ground operation last month, said: “We want President Trump to keep pushing for an end to the war, if this chance is lost, it means that Gaza City will be destroyed by Israel and we might not survive.

“Enough, two years of bombardment, death and starvation. Enough,” he told Reuters on a social media chat.

“God willing this will be the last war. We will hopefully be done with the wars,” said 59-year-old Ali Ahmad, speaking in one of the tented camps where most Palestinians now live.

“We urge all sides not to backtrack. Every day of delay costs lives in Gaza, it is not just time wasted, lives get wasted too,” said Tamer Al-Burai, a Gaza City businessman displaced with members of his family in central Gaza Strip.

After two previous ceasefires — one near the start of the war and another earlier this year — lasted only a few weeks, he said; “I am very optimistic this time, maybe Trump’s seeking to be remembered as a man of peace, will bring us real peace this time.”

RESIDENT WORRIES THAT NETANYAHU WILL ‘SABOTAGE’ DEAL

Some voiced hopes of returning to their homes, but the Israeli military issued a fresh warning to Gazans on Saturday to stay out of Gaza City, describing it as a “dangerous combat zone.”

Gazans have faced previous false dawns during the past two years, when Trump and others declared at several points during on-off negotiations between Hamas, Israel and Arab and US mediators that a deal was close, only for war to rage on.

“Will it happen? Can we trust Trump? Maybe we trust Trump, but will Netanyahu abide this time? He has always sabotaged everything and continued the war. I hope he ends it now,” said Aya, 31, who was displaced with her family to Deir Al-Balah in the central Gaza Strip.

She added: “Maybe there is a chance the war ends at October 7, two years after it began.”

RSS

Mass Rally in Rome on Fourth Day of Italy’s Pro-Palestinian Protests

A Pro-Palestinian demonstrator waves a Palestinian flag during a national protest for Gaza in Rome, Italy, October 4, 2025. Photo: REUTERS/Claudia Greco

Large crowds assembled in central Rome on Saturday for the fourth straight day of protests in Italy since Israel intercepted an international flotilla trying to deliver aid to Gaza, and detained its activists.

People holding banners and Palestinian flags, chanting “Free Palestine” and other slogans, filed past the Colosseum, taking part in a march that organizers hoped would attract at least 1 million people.

“I’m here with a lot of other friends because I think it is important for us all to mobilize individually,” Francesco Galtieri, a 65-year-old musician from Rome, said. “If we don’t all mobilize, then nothing will change.”

Since Israel started blocking the flotilla late on Wednesday, protests have sprung up across Europe and in other parts of the world, but in Italy they have been a daily occurrence, in multiple cities.

On Friday, unions called a general strike in support of the flotilla, with demonstrations across the country that attracted more than 2 million, according to organizers. The interior ministry estimated attendance at around 400,000.

Italy’s right-wing government has been critical of the protests, with Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni suggesting that people would skip work for Gaza just as an excuse for a longer weekend break.

On Saturday, Meloni blamed protesters for insulting graffiti that appeared on a statue of the late Pope John Paul II outside Rome’s main train station, where Pro-Palestinian groups have been holding a protest picket.

“They say they are taking to the streets for peace, but then they insult the memory of a man who was a true defender and builder of peace. A shameful act committed by people blinded by ideology,” she said in a statement.

Israel launched its Gaza offensive after Hamas terrorists staged a cross border attack on October 7, 2023, killing some 1,200 people and taking 251 people hostage.

RSS

Hamas Says It Agrees to Release All Israeli Hostages Under Trump Gaza Plan

Smoke rises during an Israeli military operation in Gaza City, as seen from the central Gaza Strip, October 2, 2025. Photo: REUTERS/Dawoud Abu Alkas

Hamas said on Friday it had agreed to release all Israeli hostages, alive or dead, under the terms of US President Donald Trump’s Gaza proposal, and signaled readiness to immediately enter mediated negotiations to discuss the details.