Features

New book looks at the fight by law-abiding Jews to rein in the New York Jewish underworld in early 20th century

The Incorruptibles: A True Story of Kingpins, Crime Busters, and the Birth of the American Underworld

Reviewed by BERNIE BELLAN For those readers who can remember the story of “The Untouchables,” the crime-fighting unit led by Elliot Ness, which was established by the Bureau of Prohibition in the US in the 1930s, tales of shoot-outs between courageous crime-fighting “good guys” and villainous underworld bootleggers and other assorted criminals would probably be thought of as something that wouldn’t have its origin in a Jewish-led crime-fighting unit established several years earlier.

But, would you believe that not too many years before the often bloody events that were depicted in “The Untouchables” came to pass there was another organization in New York City – led by Jewish crime fighters at that time, which had a somewhat tacit affiliation with the New York City Police Department, and whose purpose was to wage war on Jewish criminals on New York’s East Side? That organization was known as “The Incorruptibles” and the story how it came to be created is told in a fascinating new book, titled “The Incorruptibles: A True Story of Kingpins, Crime Busters, and the Birth of the American Underworld,” written by a New York crime reporter by the name of Dan Slater.

As someone who has long had a fascination with shady Jewish characters, I’ve come to realize over the years that a rollicking good story of a Jewish mobster, such as the close friendship a former Winnipegger by the name of Al Smiley had with the notorious Bugsy Siegel, about which Martin Zeilig wrote for The Jewish Post & News in March 2017, resonates with readers in ways that stories about more righteous Jews don’t.

While Martin’s story about Al Smiley was by no means the first story we’ve ever had about Jewish mobsters, a quick search of our online archive would lead you to numerous stories about Jewish gangsters and other assorted criminals.

In the summer of 2023 we ran two stories in relatively rapid succession that elicited a higher than usual amount of interest from readers. One was my review of a book called “Jukebox Empire,” about someone by the name of Wilf Rabin, who actually grew up in Morden, Manitoba. The other story was about bootlegger Bill Wolchock, written by Bill Redekopp, and which appeared in our 2023 Rosh Hashanah edition. Later, when I posted that story to our website it received so many views that I’ve returned it to our home page twice since. (You can now read that story if you missed it by reading it here: “Booze, Glorious Booze”

All this serves as a preamble to my review of “The Incorruptibles.” I have to couch what I’m about to write with an admission: As a youngster growing up in a sheltered environment, and attending the Talmud Torah, where all we were ever told about was Jewish “heroes,” and the only villains were Jews who didn’t lead properly observant lives, reading “The Incorruptibles” came as a real shock to my conception of how much Jews could be associated with the most sordid type of criminal activity.

It’s one thing to realize that many Jews were involved with bootlegging – something that has developed an almost romantic connotation over the years through books, movies and television programs, but to learn that in the latter part of the 19th century Jews in New York were in control of that city’s: prostitution (and most prostitutes were Jewish!); drugs (however, with the understanding that drugs, including heroin and cocaine, were legally available in the U.S. until 1907 and could be readily purchased in pharmacies); gambling; and protection rackets – does come as somewhat of a shock to a sheltered Winnipeg Jew.

Dan Slater’s depiction of life in New York City at the turn of the 20th century is unremittingly harrowing. For the first part of the 20th century the lower East Side of New York was the most densely populated area on Earth. Housing conditions were horrible and the hundreds of thousands of new immigrants arriving yearly – beginning in the 1870s, from what was known as the Pale of Settlement in Eastern Europe – fleeing persecution and pogroms, found themselves being shunted into unspeakably barbaric working conditions in lower East Side factories, predominantly garment factories – owned by fellow Jews. (The author actually spends a considerable amount of time explaining how exactly the Pale of Settlement came into being and how sudden and incredibly violent wholesale persecution of hundreds of thousands of Jews could happen almost overnight – with the death of a particular czar, for instance.)

It was amidst this churning cesspool of a city that Jewish criminal activity of all sorts ran rampant. Two images from “The Incorruptibles” in particular haunted me. One was Slater’s explanation how so many young Russian Jewish women – most in their early or mid-teens, and only recently arrived in New York, were forced into prostitution. Many of these young women would go to a dance – looking to find some relief from the slave-like conditions that permeated the factories in which they worked. While at the dance, they would be approached by a young Jewish man who would offer them a drink. These guys, known in the colloquial as “Alphonses,” or, in Yiddish, as “schimchas,” would lace the girls’ drinks with drugs (a common occurrence to this day) and take the girls home, where they would rape them. But – now defiled, the girl could not possibly return to her family home out of shame; thus, tens of thousands of young Jewish women were forced into prostitution.

The other image that haunts me was the widespread practice of “horse poisoning.” Protection rackets have probably been around from time immemorial, but in this particular incarnation, criminals would confront business owners with a choice: Pay for “protection” or see your means of transportation (and remember, this was at a time when a horse-drawn buggy or carriage was the principal means of transportation) poisoned.

(There is actually a photo in “The Incorruptibles” of a horse lying dead on a New York street after it had been poisoned. Apparently it happened on a regular basis to the point where it didn’t draw much attention.)

While the book chronicles one sordid story after another so that the reader can understand just how tough life was on the lower East Side – often with reference to the colourful names of some of the most famous Jewish thugs who terrorized their fellow Jews, such as “Bald Jack Rose” or “Big Jack Zelig” (no relation to Martin Zelig – I checked), the biggest mobster of them all was the legendary Arnold Rothstein.

Rothstein is undoubtedly most famous for reputedly having fixed the 1919 World Series by bribing eight members of the Chicago White Sox, the overwhelming favourite to defeat the Cincinnati Reds, to throw the series. (It has never been proven absolutely conclusively that Rothstein did that, but as “The Incorruptibles” explains, the evidence points overwhelmingly in his direction.)

Rothstein was the kind of gambler who could lose $350,000 in a single night of playing poker – and not worry about it.

Here is an example of Slater’s ability to describe a character, when he sums up Arnold Rothstein: “Picture in one individual a sentimental and tender lover, a genial and humorous companion, a charitable giver, a loyal friend—and—a wholesale drug dealer, a crooked sports fixer, a welching gambler, a stolen securities fence, a rum-ring mastermind, a corrupter of police, a grafter through politics, a gunman, a judge-briber, a jury-tamperer, a blackmailer, a pool shark, a swindler.”

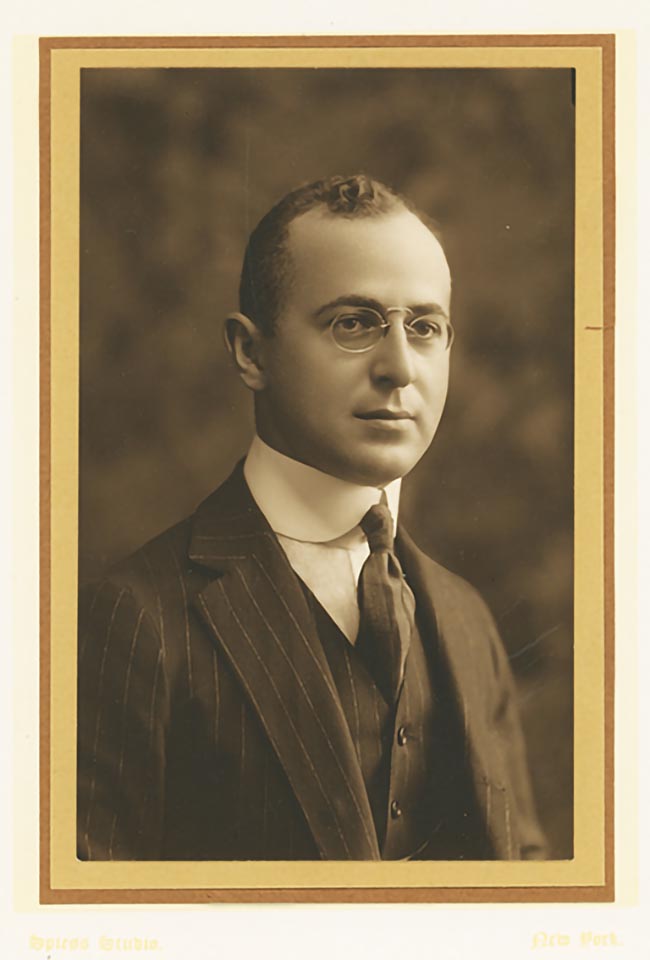

But, up against the villains of “The Incorruptibles,” Slater also depicts the stories of two very talented – and brave, young Jewish men, who were willing to challenge the criminal class: A lawyer by the name of Harry Newburger and Abe Shoenfeld, the son of a well-known New York reformer by the name of Mayer Shoenfeld.

As Slater explains, it was only when members of New York’s largely German-Jewish upper class began to take note of the horrid conditions in which the vast majority of the Eastern European Jews who had recently immigrated to America were living did an impetus to try and change things develop. Two men, Jacob Schiff (who is described as the J.P. Morgan of his day in terms of his vast wealth), and Felix Warburg, together with the rabbi of the leading temple of its day, Rabbi Judah Magnes of Temple Immanu-El, organized a group known as the “Kehilah.”

The Kehilah mandated Newburger and Shoenfeld to do whatever they deemed necessary to begin cleaning up the lower East Side. Of course, given how corrupt New York officials were at the time – under the control of the notorious Tammany Hall, led by “Big Jim Sullivan,” most of the New York City Police Department was also thoroughly under the control of criminals, which made the challenge set out for Newburger and Shoenfeld all the more difficult.

The book describes, sometimes in painful detail, the difficulties faced by the group assembled by Newburger and Shoenfeld, known, naturally, as “The Incorruptibles.” They weren’t above busting heads themselves, it turns out.

Again, one of the more interesting aspects of history to emerge from this book is that men would often switch sides at the drop of a hat – to go from violently attacking one particular group – at the behest of this or that mobster, to attacking the same group they were supposed to be defending the next day.

As has already been noted, the garment trade played a pivotal role in the development of New York City into becoming not only a magnet for immigrants, it also also played a prominent role in New York’s becoming the vast economic powerhouse that it is today. Slater notes that, at one point, 80 percent of all garments produced in the U.S. came from the lower East Side.

As workers began to organize themselves into unions, garment factory owners hired thugs, known as “shtarkers” (strong men) to beat up workers, occasionally to kill union organizers. In time though, the tide began to turn and, as unions gathered strength, the same tactics of violence and intimidation that had been used against workers began to be employed by unions – with workers who dared to cross picket lines (known colloquially as “scabs”) often being on the receiving end of that violence, occasionally ending with them being killed.

Newburger and Shoenfeld were thrust into the midst of this turmoil, trying to bring some peace to the labour disputes. Ironically, Mayer Shoenfeld (Abe’s father) was a longtime advocate for workers’ rights, but he would not talk to his son, who tried to straddle both worlds – of employers and employees.

“The Incorruptibles” describes the many battles fought to rein in the gambling, prostitution, protection rackets, and what became the illegal drug trade that were part and parcel of life on New York’s East Side. As the years went by, the Jewish dominance of the New York underworld gave way to the ascendance of the Italian mob. (Slater also acknowledges the roles that other groups also played in New York criminal activity, including the Irish), but his main focus is on Jewish criminals.

“The Incorruptibles” is a long and detailed book, drawing upon a great many different sources, and at times, the proliferation of names entering the scene can be more than a little confusing. But, for anyone who has an interest in reading something that peels back the layers of a very disturbing aspect of Jewish history that might not fit all that well with the notion of Jewish righteousness, then “The Incorruptibles” might be of interest.

“The Incorruptibles: A True Story of Kingpins, Crime Busters, and the Birth of the American Underworld”

By Dan Slater

432 pages

Published by Little, Brown and Company, 2024

Features

ClarityCheck: Securing Communication for Authors and Digital Publishers

In the world of digital publishing, communication is the lifeblood of creation. Authors connect with editors, contributors, and collaborators via email and phone calls. Publishers manage submissions, coordinate with freelance teams, and negotiate contracts online.

However, the same digital channels that enable efficient publishing also carry risk. Unknown contacts, fraudulent inquiries, and impersonation attempts can disrupt projects, delay timelines, or compromise sensitive intellectual property.

This is where ClarityCheck becomes a vital tool for authors and digital publishers. By allowing users to verify phone numbers and email addresses, ClarityCheck enhances trust, supports safer collaboration, and minimizes operational risks.

Why Verification Matters in Digital Publishing

Digital publishing involves multiple types of external communication:

- Manuscript submissions

- Editing and proofreading coordination

- Author-publisher negotiations

- Marketing and promotional campaigns

- Collaboration with illustrators and designers

In these workflows, unverified contacts can lead to:

- Scams or fraudulent project offers

- Intellectual property theft

- Miscommunication causing delays

- Financial loss due to fraudulent payments

- Unauthorized sharing of sensitive drafts

Platforms like Reddit feature discussions from authors and freelancers about using verification tools to safeguard their work. This highlights the growing awareness of digital safety in creative industries.

What Is ClarityCheck?

ClarityCheck is an online service that enables users to search for publicly available information associated with phone numbers and email addresses. Its primary goal is to provide additional context about a contact before initiating or continuing communication.

Rather than relying purely on intuition, authors and publishers can access structured information to assess credibility. This proactive approach supports safer project management and protects intellectual property.

You can explore community feedback and discussions about the service here: ClarityCheck

Key Benefits for Authors and Digital Publishers

1. Protecting Manuscript Submissions

Authors often submit manuscripts to multiple editors or publishers. Before sharing full drafts:

- Verify the contact’s legitimacy

- Ensure the communication aligns with known publishing entities

- Reduce risk of unauthorized distribution

A quick lookup can prevent time-consuming disputes and protect original content.

2. Safeguarding Collaborative Projects

Digital publishing frequently involves external contributors such as:

- Illustrators

- Designers

- Editors

- Ghostwriters

Verification ensures all collaborators are trustworthy, minimizing the chance of intellectual property theft or miscommunication.

3. Enhancing Marketing and PR Outreach

Promoting a book or digital publication often involves connecting with:

- Bloggers

- Reviewers

- Book influencers

- Digital media outlets

Before sharing press kits or marketing materials, verifying email addresses or phone contacts adds confidence and prevents potential misuse.

How ClarityCheck Works

While the internal system is proprietary, the user workflow is straightforward and efficient:

| Step | Action | Outcome |

| 1 | Enter phone number or email | Search initiated |

| 2 | Aggregation of publicly available data | Digital footprint analyzed |

| 3 | Report generated | Structured overview presented |

| 4 | Review by user | Informed decision before engagement |

The platform’s simplicity makes it suitable for authors and publishing teams, even those with limited technical expertise.

Integrating ClarityCheck Into Publishing Workflows

Manuscript Submission Process

- Receive submission request

- Verify contact via ClarityCheck

- Confirm identity of editor or publisher

- Share draft or proceed with collaboration

Collaboration with Freelancers

- Initiate project with external contributors

- Run ClarityCheck to verify email or phone number

- Establish project agreement

- Begin content creation safely

Marketing Outreach

- Contact media or reviewers

- Verify digital identity

- Share promotional materials with confidence

Ethical and Privacy Considerations

While ClarityCheck provides useful context, it operates exclusively using publicly accessible information. Authors and publishers should always:

- Respect privacy and data protection regulations

- Use results responsibly

- Combine verification with personal judgment

- Avoid sharing sensitive data with unverified contacts

Responsible use ensures the platform supports security without compromising ethical standards.

Real-World Use Cases in Digital Publishing

Scenario 1: Verifying a New Editor

An author is contacted by an editor claiming to represent a small publishing house. Running a ClarityCheck report confirms the email domain aligns with publicly available information about the company, reducing risk before signing an agreement.

Scenario 2: Screening Freelance Illustrators

A digital publisher seeks an illustrator for a children’s book. Before sharing project details or compensation terms, ClarityCheck verifies contact information, ensuring the artist is legitimate.

Scenario 3: Marketing Outreach Safety

A self-publishing author plans a social media and email campaign. Verifying influencer or reviewer contacts helps prevent marketing materials from reaching fraudulent accounts.

Why Verification Strengthens Publishing Operations

In digital publishing, speed and creativity are essential, but they must be balanced with security:

- Protect intellectual property

- Maintain trust with collaborators

- Ensure financial transactions are secure

- Prevent delays due to miscommunication

Verification tools like ClarityCheck integrate seamlessly, allowing authors and publishing teams to focus on creation rather than risk management.

Final Thoughts

In a world where publishing is increasingly digital and collaborative, verifying contacts is not just prudent — it’s necessary.

ClarityCheck empowers authors, editors, and digital publishing professionals to confidently assess phone numbers and email addresses, protect their intellectual property, and streamline communication.

Whether managing manuscript submissions, coordinating external contributors, or launching marketing campaigns, integrating ClarityCheck into your workflow ensures clarity, safety, and professionalism.

In digital publishing, trust is as important as creativity — and ClarityCheck helps safeguard both.

Features

Israel’s Arab Population Finds Itself in Dire Straits

By HENRY SREBRNIK There has been an epidemic of criminal violence and state neglect in the Arab community of Israel. At least 56 Arab citizens have died since the beginning of this year. Many blame the government for neglecting its Arab population and the police for failing to curb the violence. Arabs make up about a fifth of Israel’s population of 10 million people. But criminal killings within the community have accounted for the vast majority of Israeli homicides in recent years.

Last year, in fact, stands as the deadliest on record for Israel’s Arab community. According to a year-end report by the Center for the Advancement of Security in Arab Society (Ayalef), 252 Arab citizens were murdered in 2025, an increase of roughly 10 percent over the 230 victims recorded in 2024. The report, “Another Year of Eroding Governance and Escalating Crime and Violence in Arab Society: Trends and Data for 2025,” published in December, noted that the toll on women is particularly severe, with 23 Arab women killed, the highest number recorded to date.

Violence has expanded beyond internal criminal disputes, increasingly affecting public spaces and targeting authorities, relatives of assassination targets, and uninvolved bystanders. In mixed Arab-Jewish cities such as Acre, Jaffa, Lod, and Ramla, violence has acquired a political dimension, further eroding the fragile social fabric Israel has worked to sustain.

In the Negev, crime families operate large-scale weapons-smuggling networks, using inexpensive drones to move increasingly advanced arms, including rifles, medium machine guns, and even grenades, from across the borders in Egypt and Jordan. These weapons fuel not only local criminal feuds but also end up with terrorists in the West Bank and even Jerusalem.

Getting weapons across the border used to be dangerous and complex but is now relatively easy. Drones originally used to smuggle drugs over the borders with Egypt and Jordan have evolved into a cheap and effective tool for trafficking weapons in large quantities. The region has been turning into a major infiltration route and has intensified over the past two years, as security attention shifted toward Gaza and the West Bank.

The Negev is not merely a local challenge; it serves as a gateway for crime and terrorism across Israel, including in cities. The weapons flow into mixed Jewish-Arab cities and from there penetrate the West Bank, fueling both organized crime and terrorist activity and blurring the line between them.

The smuggling of weapons into Israel is no longer a marginal criminal phenomenon but an ongoing strategic threat that traces a clear trail: from porous borders with Egypt and Jordan, through drones and increasingly sophisticated smuggling methods, into the heart of criminal networks inside Israel, and in a growing number of cases into lethal terrorist operations. A deal that begins as a profit-driven criminal transaction often ends in a terrorist attack. Israeli police warn that a population flooded with illegal weapons will act unlawfully, the only question being against whom.

The scale of the threat is vast. According to law enforcement estimates, up to 160,000 weapons are smuggled into Israel each year, about 14,000 a month. Some sources estimate that about 100,000 illegal weapons are circulating in the Negev alone.

Israeli cities are feeling this. Acre, with a population of about 50,000, more than 15,000 of them Arab, has seen a rise in violent incidents, including gunfire directed at schools, car bombings, and nationalist attacks. In August 2025, a 16-year-old boy was shot on his way to school, triggering violent protests against the police.

Home to roughly 35,000 Arab residents and 20,000 Jewish residents, Jaffa has seen rising tensions and repeated incidents of violence between Arabs and Jews. In the most recent case, on January 1, 2026, Rabbi Netanel Abitan was attacked while walking along a street, and beaten.

In Lod, a city of roughly 75,000 residents, about half of them Arab, twelve murders were recorded in 2025, a historic high. The city has become a focal point for feuds between crime families. In June 2025, a multi-victim shooting on a central street left two young men dead and five others wounded, including a 12-year-old passerby. Yet the killing of the head of a crime family in 2024 remains unsolved to this day; witnesses present at the scene refused to testify.

The violence also spilled over to Jewish residents: Jewish bystanders were struck by gunfire, state officials were targeted, and cars were bombed near synagogues. Hundreds of Jewish families have left the city amid what the mayor has described as an “atmosphere of war.”

Phenomena that were once largely confined to the Arab sector and Arab towns are spilling into mixed cities and even into predominantly Jewish cities. When violence in mixed cities threatens to undermine overall stability, it becomes a national problem. In Lod and Jaffa, extortion of Jewish-owned businesses by Arab crime families has increased by 25 per cent, according to police data.

Ramla recorded 15 murders in 2025, underscoring the persistence of lethal violence in the city. Many victims have been caught up in cycles of revenge between clans, often beginning with disputes over “honour” and ending in gunfire. Arab residents describe the city as “cursed,” while Jewish residents speak openly about being afraid to leave their homes

Reluctance to report crimes to the authorities is a central factor exacerbating the problem. Fear of retaliation by families or criminal organizations deters victims and their relatives from coming forward, contributing to a clearance rate of less than 15 per cent of all murders. The Ayalef report notes that approximately 70 per cent of witnesses refused to cooperate with police investigations, citing doubts about the state’s ability to provide protection.

Violence in Arab society is not just an Arab sector problem; it poses a direct and serious threat to Israel’s national security. The impact is twofold: on the one hand, a rise in crime that affects the entire population; on the other, the spillover of weapons and criminal activity into terrorism, threatening both internal and regional stability. This phenomenon reached a peak in 2025, with implications that could lead to a third intifada triggered by either a nationalist or criminal incident.

The report suggests that along the Egyptian and Jordanian borders, Israel should adopt a technological and security-focused response: reinforcing border fences with sensors and cameras, conducting aerial patrols to counter drones, and expanding enforcement activity.

This should be accompanied by a reassessment of the rules of engagement along the border area, enabling effective interdiction of smuggling and legal protocols that allow for the arrest and imprisonment of offenders. The report concludes by emphasizing that rising violence in cities, compounded by weapons smuggling in the Negev, is eroding Israel’s internal stability.

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.

Features

The Chapel on the CWRU Campus: A Memoir

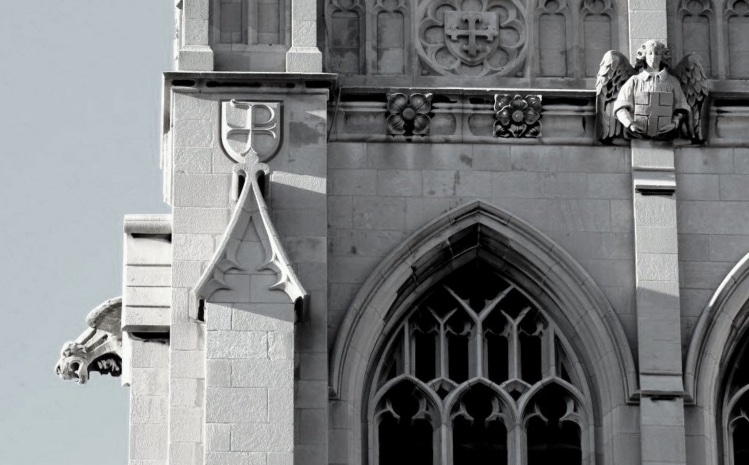

By DAVID TOPPER In 1964, I moved to Cleveland, Ohio to attend graduate school at Case Institute of Technology. About a year later, I met a girl with whom I fell in love; she was attending Western Reserve University. At that time, they were two entirely separate schools. Nonetheless, they share a common north-south border.

Since Reserve was originally a Christian college, on that border between the two schools there is a Chapel on the Reserve (east) side, with a four-sided Tower. On the top of the Tower are three angels (north, east, & south) and a gargoyle (west); the latter therefore faces the Case side. Its mouth is a waterspout – and so, when it rains, the gargoyle spits on the Case side. The reason for this, I was told, is that the founder of Case, Leonard Case Jr., was an atheist.

In 1968, that girl, Sylvia, and I got married. In the same year the two schools united, forming what is today still Case Western Reserve University (CWRU). I assume the temporal proximity of these two events entails no causality. Nevertheless, I like the symbolism, since we also remain married (although Sylvia died almost 6 years ago).

Speaking of symbolism: it turns out that the story told to me is a myth. Actually, Mr. Case was a respected member of the Presbyterian Church. Moreover, the format of the Tower is borrowed from some churches in the United Kingdom – using the gargoyle facing west, toward the setting sun, to symbolize darkness, sin, or evil. It just so happens that Case Tech is there – a fluke. Just a fluke.

We left Cleveland in 1970, with our university degrees. Harking back to those days, only once during my six years in Cleveland, was I in that Chapel. It was the last day before we left the city – moving to Winnipeg, Canada – where I still live. However, it was not for a religious ceremony – no, not at all. Sylvia and I were in the Chapel to attend a poetry reading by the famed Beat poet, Allen Ginsberg.

My final memory of that Chapel is this. After the event, as we were walking out, I turned to Sylvia and said: “I’m quite sure that this is the first and only time in the entire long history of this solemn Chapel that those four walls heard the word ‘fuck’.” Smiling, she turned to me and said, “Amen.”

This story was first published in “Down in the Dirt Magazine,”

vol, 240, Mars and Cotton Candy Clouds.