Local News

Jewish population of Winnipeg shows slight increase in past 10 years – but 2021 census does not give definitive answers as to what the size of our Jewish population really is

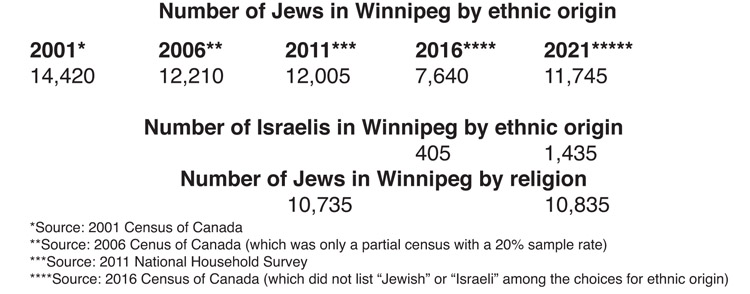

By BERNIE BELLAN The number of individuals in Winnipeg who report that their ethnic origin is Jewish has declined somewhat from the number reported in the 2011 National Household Survey (which was the last reliable report on the ethnic and religious composition of Canada produced by StatsCan).

However, set against the decline in the number of Winnipeggers who reported their ethnic origin as Jewish was a marked increase in the number that reported their ethnic origin was Israeli.

The number of individuals who reported their religion was Jewish also showed a very slight increase from 2011 to 2021.

Those are some of the most significant findings from the latest release of detailed information from the 2021 census, which came on October 26, when StatsCan released a whole trove of documents about immigration and ethnicity – with statistics about religion at the very end of the document release.

According to the 2021 census, 11,745 individuals in Winnipeg reported their ethnic origin as Jewish. In 2011 the figure was 12,005. However, considering that 1,435 individuals reported their ethnic origin was Israeli (as opposed to a total of 340 in 2011), when you add the two figures together the total comes to 13,180.

As for religion, the number of Winnipeggers who said their religion was Jewish stood at 10,740 in 2011. The 2021 census reported the number as 10,835, an increase of 95.

We have been waiting anxiously for the results of the 2021 census ever since results from the 2016 census were so wildly inconsistent with all previous census results when it came to showing that the number of Jews, not only in Winnipeg, but everywhere in Canada, had declined precipitously.

As we have been reporting repeatedly ever since results of the 2016 census were published, the reason for what were considered aberrant results in the 2016 census was that, for the first time, “Jewish” was not listed among the 20 choices for ethnic ancestry in that census. Instead, one would have had to write in “Jewish” as an answer. As a result, even StatsCan conceded that the low number of individuals who responded that their ethnic origins were Jewish was unrealistically low.

In the 2016 census also, the likelihood is that a number of respondents who might otherwise have responded “Jewish” if it had been given in the list of examples of ethnic origin, instead likely chose “Canadian,” since Canadian was one of the 20 examples listed.

As a report from StatsCan noted, “After the 2016 Census, concerns were raised that changes to the list of examples of ethnic and cultural origins included as part of the question were affecting response patterns. Concerns were also raised about the wordiness of the question, which made it difficult for certain people to read and respond to the question.”

StatsCan went on to explain that “respondents were more likely to report an origin when it was included in the list of examples and, conversely, less likely to report an origin if it was not included in the list.”

As a result, StatsCan made major changes to how ethnic origin was tabulated in the 2021 census. The question that was asked was the same as what had been asked in previous censuses: “What were the ethnic or cultural origins of this person’s ancestors?”

That question was followed by a further explanation:

“Ancestors may have Indigenous origins, or origins that refer to different countries, or other origins that may not refer to different countries.

But the 2021 census, which was required to be filled out online, actually gave a link to “a list of over 500 examples of ethnic and cultural origins,” of which both “Jewish” and “Israeli” were among the choices.

One might well wonder though whether many recent immigrants to Winnipeg who might be considered ostensibly Jewish might also have filled in different ethnic origins, especially individuals with Eastern European roots. (There was only room for one answer to the question about ethnic origins.)

But then we run up against the issue of the relatively low number of individuals who said their religion was “Jewish” in the 2021 census.

The religion question that appeared in the 2021 Census, “What is this person’s religion?” was the same as the one that was asked in the 2011 National Household Survey and in the 2001 and 1991 censuses. It also had the same basic format: there was a write-in box in which respondents could report their religion, as well as a mark-in circle for indicating “No religion.”

Thus, while one might posit that a certain number of immigrants to Winnipeg might have Jewish roots, if they didn’t answer that their ethnic origins were either “Jewish” or “Israeli” and they also didn’t indicate that their religion was “Jewish”, is it fair still to consider them Jewish?

In an interview I conducted in August with Faye Rosenberg-Cohen, who is about to retire as the Jewish Federation’s Chief Planning and Allocations Officer, I asked Faye how many immigrants make up the Jewish population of Winnipeg now?

Faye responded: “I can honestly say when I look at those numbers it’s somewhere around 1/3 of the community.”

JP&N: “So you’d say it’s somewhere between 4-5,000?”

Faye: “I think it’s more than that.”

If what Faye said was true then the Jewish community would number at least 15,000.

I indicated my skepticism at that time, saying “You know that I’ve always been skeptical about the numbers that have been used by the Federation for the population of the Jewish community. I think though that it’s always been more of a case of identification – who identifies as Jewish?”

In the final analysis, there is nothing in what StatsCan has just reported that would back up the notion that our Jewish population here is over 15,000. Yet, there is one more possibility that might allow the Jewish Federation to argue that our population is closer to 15,000. That will require a more detailed analysis comparing the results for respondents who said their religion was “Jewish” but their ethnic origin was not.

Following the 2011 National Household Survey, which was the first census that showed a sizeable drop in the size of our Jewish population, I entered into an email exchange with a statistician from StatsCan as to whether it was possible that our Jewish population was much larger than 12,010, which was how many respondents indicated their ethnic origin was Jewish back in 2011.

That statistician did a much deeper analysis of the data than was available to me. He showed that of the 10,740 individuals who said their religion was Jewish, only 7,885 reported that their ethnic origin was Jewish. That was a difference of 2,885. (Clearly there have been a lot of converts within our community). If you added those respondents who said their religion was Jewish, but not their ethnic origin, to the number of respondents who said their ethnic origin was Jewish, you came up with a figure of 14,885. That figure would have been much closer to what the Federation was saying was the size of our Jewish population in 2011.

Is it important? Well, as I’ve been arguing for years, if our Federation is basing its plans for the future on a notion that our Jewish population is much bigger than what is really the case, then those plans are misguided.

Gray Academy has far fewer students than was the case just ten years ago. Brock Corydon, the only other school that offers any sort of an exposure to a Jewish curriculum, also has fewer Jewish students than used to be the case. The Simkin Centre has a very high proportion of non-Jewish residents. Our synagogues have lost huge numbers of members. None of these changes would be reflective of a growing Jewish population.

However, as I’ve just noted, there is a very real possibility that our Jewish population is closer to the figure of 15,000 – which is the figure commonly cited by spokespersons for the Federation. In order to find out though whether that is the case, we’ll need someone at StatsCan to do a similar analysis of data that was done at my request following the 2011 National Household Survey. I’ve already sent a request to StatsCan for a more comprehensive analysis of the answers to the questions about ethnic origin and religion, similar to what was done for me by a StatsCan analyst following the 2011 National Household Survey. We’re hoping to have further answers to the question of how many Jews there are in Winnipeg in a future issue – if we hear back from someone at StatsCan.

Local News

Winnipeg Jewish Theatre breaks new ground with co-production with Rainbow Stage

By MYRON LOVE Winnipeg Jewish Theatre is breaking new ground with its first ever co-production with Rainbow Stage. The new partnership’s presentation of “Fiddler on the Roof” is scheduled to hit the stage at our city’s famed summer musical theatre venue in September 2026.

“We have collaborated with other theatre companies in joint productions before,” notes Dan Petrenko, the WJT’s artistic and managing director – citing previous partnerships with the Segal Centre for the Performing Arts in Montreal, the Harold Green Jewish Theatre in Toronto, Persephone Theatre in Saskatoon and Winnipeg’s own Dry Cold Productions. “Because of the times we’re living through, and particularly the growing antisemitism in our communities and across the country, I felt there is a need to tell a story that celebrates Jewish culture on the largest stage in the city – to reach as many people as possible.”

Last year, WJT approached Rainbow Stage with a proposal for the co-presentation of “Fiddler on the Roof.” Rainbow Stage management was really enthusiastic in their response, Petrenko reports.

“We are excited to be working with Winnipeg’s largest musical theatre company,” he notes. “Rainbow Stage has an audience of more than 10,000 people every season. Fiddler is a great, family-oriented story and, through our joint effort with Rainbow Stage, WJT will be able to reach out to new and younger audiences.”

“We are also working to welcome more diverse audiences from other communities, as well as newcomers – families who have moved here from Israel, Argentina and countries of the former Soviet Union.”

Helping Petrenko to achieve those goals are two relatively new and younger additions to WJT’s management team. Both Company Manager Etel Shevelev, and Head of Marketing Julia Kroft are in their 20s – as is Petrenko himself.

Kroft, who is also Gray Academy’s Associate Director of Advancement and Alumni Relations, needs little or no introduction to many readers. In addition to her work for Gray Academy and WJT, the daughter of David and Ellen Kroft has been building a second career as a singer and actor. Over the past few years, she has performed by herself or as part of a musical ensemble at Jewish community events, as well as in various professional theatre productions in the city.

Etel Shevelev is also engaged in a dual career. In addition to working full time at WJT, she is also a Fine Arts student (majoring in graphic design) at the University of Manitoba. Outside of school, she is an interdisciplinary visual artist (exhibiting her work and running workshops), so you can say the art world is no stranger to her.

(She will be partcipating in Limmud next month as a member of the Rimon Art Collective.)

Shevelev grew up in Kfar Saba (northeast of Tel Aviv). She reports that in Israel she was involved in theatre from a young age. “In 2019, I graduated from a youth theatre school, which I attended for 11 years.” In a sense, her work for WJT brings her full circle.

She arrived in Winnipeg just six years ago with her parents. “I was 19 at the time,” she says.

After just a year in Winnipeg, her family decided to relocate to Ottawa, while she chose to stay here. “I was already enrolled in university, had a long-term partner, and a job,” she explains. “I felt that I was putting down roots in Winnipeg.”

Etel expects to graduate by the end of the academic year, allowing her to focus on the arts professionally full-time.

In her role as company manager, Shevelev notes, she is responsible for communications with donors, contractors, and unions, as well as applying for various grants and funding opportunities.

In addition, her linguistic skills were put to use last spring for WJT’s production of “The Band’s Visit,” a story about an Egyptian band that was invited to perform at a cultural centre opening ceremony in the lively centre of Israel, but ended up in the wrong place – a tiny, communal town in southern Israel. Shevelev was called on to help some of the performers with the pronunciation of Hebrew words and with developing a Hebrew accent.

“I love working for WJT,” she enthuses. “Every day is different.”

Shevelev and Petrenko are also enthusiastic about WJT’s next production – coming up in April: “Ride: The Musical” debuted in London’s West End three years ago, and then went on to play at San Diego’s Old Globe theatre to rave reviews. The WJT production will be the Canadian premiere!

The play, Petrenko says, is based on the true story of Annie Londonderry, a young woman – originally from Latvia, who, in 1894, beat all odds and became the first woman to circle the world on a bicycle.

Petrenko is also happy to announce that the director and choreographer for the production will be Lisa Stevens – an Emmy Award nominee and Olivier Award winner. (The Olivier is presented annually by the Society of London Theatre to recognize excellence in professional London theatre).

“Lisa is in great demand across Canada, and the world really,” the WJT artistic director says. “I am so thrilled that we will be welcoming one of the greatest Jewish directors and choreographers of our time to Winnipeg this Spring.”

For more information about upcoming WJT shows, readers can visit wjt.ca, email the WJT office at info@wjt.ca or phone the box office at 204-477-7515.

Local News

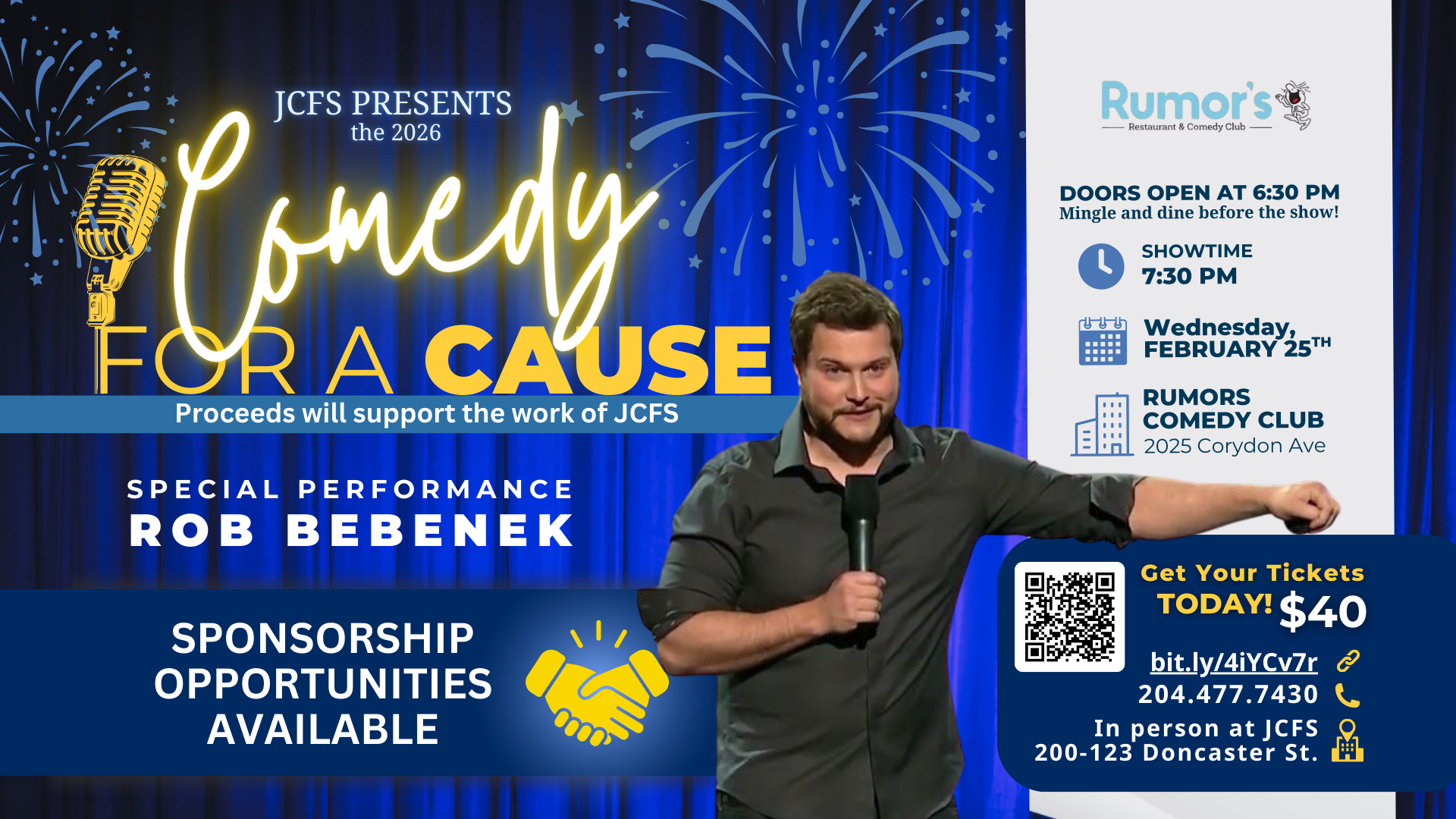

Rising Canadian comedy star Rob Bebenek to headline JCFS’ second annual “Comedy for a Cause”

By MYRON LOVE Last year, faced with a federal government budget cut to its Older Adult Services programs, Jewish Child and Family Service launched a new fundraising initiative. “Comedy with a Cause” was held at Rumor’s Comedy club and featured veteran Canadian stand-up comic Dave Hemstad.

That evening was so successful that – by popular demand – JCFS is doing an encore. “We were blown away by the support from the community,” says Al Benarroch, JCFS’s president and CEO.

“This is really a great way to support JCFS by being together and having fun,” he says.

“Last year, JCFS was able to sell-out the 170 tickets it was allotted by Rumor’s,” adds Alexis Wenzowski, JCFS’s COO. “There were also general public attendees at the event last year. Participants enjoyed a fun evening, complete with a 50/50 draw and raffle. We were incredibly grateful for those who turned out, the donors for the raffle baskets, and of course, Rumor’s Comedy Club.

“Feedback was very positive about it being an initiative that encouraged people to have fun for a good cause: our Older Adult Services Team.”

This year’s “Comedy for a Cause” evening is scheduled for Wednesday, February 25. Wenzowski reports that this year’s featured performer, Rob Bebenek, first made a splash on the Canadian comedy scene at the 2018 Winnipeg Comedy festival. He has toured extensively throughout North America, appearing in theatres, clubs and festivals. He has also made several appearances on MTV as well as opening shows for more established comics, such as Gerry Dee and the late Bob Saget.

For the 2026 show, Wenzowski notes, Rumors’ is allotting JCFS 200 tickets. As with last year, there will also be some raffle baskets and a 50/50 draw.

“Our presenting sponsors for the evening,” she reports, “are the Vickar Automotive Group and Kay Four Properties Incorporated.”

The funds raised from this year’s comedy evening are being designated for the JCFS Settlement and Integration Services Department. “JCFS chose to do this because of our reduction in funding last year by the federal government to this department,” Wenzowski points out.

“Last year alone,” she reports, “our Settlement and Integration Services team settled 118 newcomer families – from places like Israel, Mexico, Brazil, and Argentina. Each year, our program supports even more newcomer families with things like case management, supportive counselling, employment coaching, workshops, programming for newcomer seniors, and more.”

“We hope to raise more than $15,000 through this event for our Settlement and Integration Program,” Al Benarroch adds. “The team does fantastic work, and we know that our newcomer Jewish families need the supports from JCFS. I want to thank our sponsors, Rumor’s Comedy Club, and attendees for supporting us.”

Tickets for the show cost $40 and are available to purchase by calling JCFS (204-477-7430) or by visiting here: https://www.zeffy.com/en-CA/ticketing/jcfs-comedy-for-a-cause. Sponsorships are still available.

Local News

Ninth Shabbat Unplugged highlight of busy year for Winnipeg Hillel

By MYRON LOVE Lindsay Kerr, Winnipeg’s Hillel director, is happy to report that this year’s ninth Shabbat UnPlugged, held on the weekend of January 9-11, attracted approximately 90 students from 11 different universities, including 20 students who were from out of town.

Shabbat UnPlugged was started in 2016 by (now-retired) Dr. Sheppy Coodin, who was a science teacher at Gray Academy, along with fellow Gray Academy teacher Avi Posen (who made aliyah in 2019) – building on the Shabbatons that Gray Academy had been organizing for the school’s high school students for many years.

The inaugural Shabbat UnPlugged was so successful that Coodin and Posen did it again in 2017 and took things one step further by combining their Shabbat UnPlugged with Hillel’s annual Shabbat Shabang Shabbaton that brings together Jewish university students from Winnipeg and other Jewish university students from Western Canada.

As in the past, this year’s Shabbat UnPlugged weekend was held at Lakeview’s Hecla Resort. “What we like about Hecla,” Kerr notes, “is that they let us bring in our own kosher food, it is out of the city and close to nature for those who want to enjoy the outdoors.”

The weekend retreat traditionally begins with a candle lighting, kiddush and a traditional Shabbat supper. Unlike previous Shabbats UnPlugged, Kerr points out, there were no outside featured speakers this year. All religious services and activities were led by students or national program partners.

The weekend was funded in part by grants from CJPAC and StandWithUs Canada, along with the primary gift from The Asper Foundation.

Kerr reports that the activities began with 18 of our local Jewish university students participating in a new student Shabbaton – inspired by Shabbat Unplugged, titled “Roots & Rising.”

In addition to Shabbat Unplugged, Hillel further partnered with Chabad for a Sukkot program in the fall, as well as with Shaarey Zedek Congregation and StandWithUs Canada for a Chanukah program. Hillell also featured a commemoration of October 7, an evening of laser tag and, in January, a Hillel-led afternoon of ice skating.

Coming up this month will be a visit to an Escape Room – and a traditional Shabbat dinner in March.

Kerr estimates that there are about 300 Jewish students at the University of Manitoba and 100 at the University of Winnipeg.

“Our goal is to attract more Jewish students to take part in our programs and connect with our community,” she comments.