Uncategorized

Sarah Hurwitz wants Jews to stop apologizing and start learning

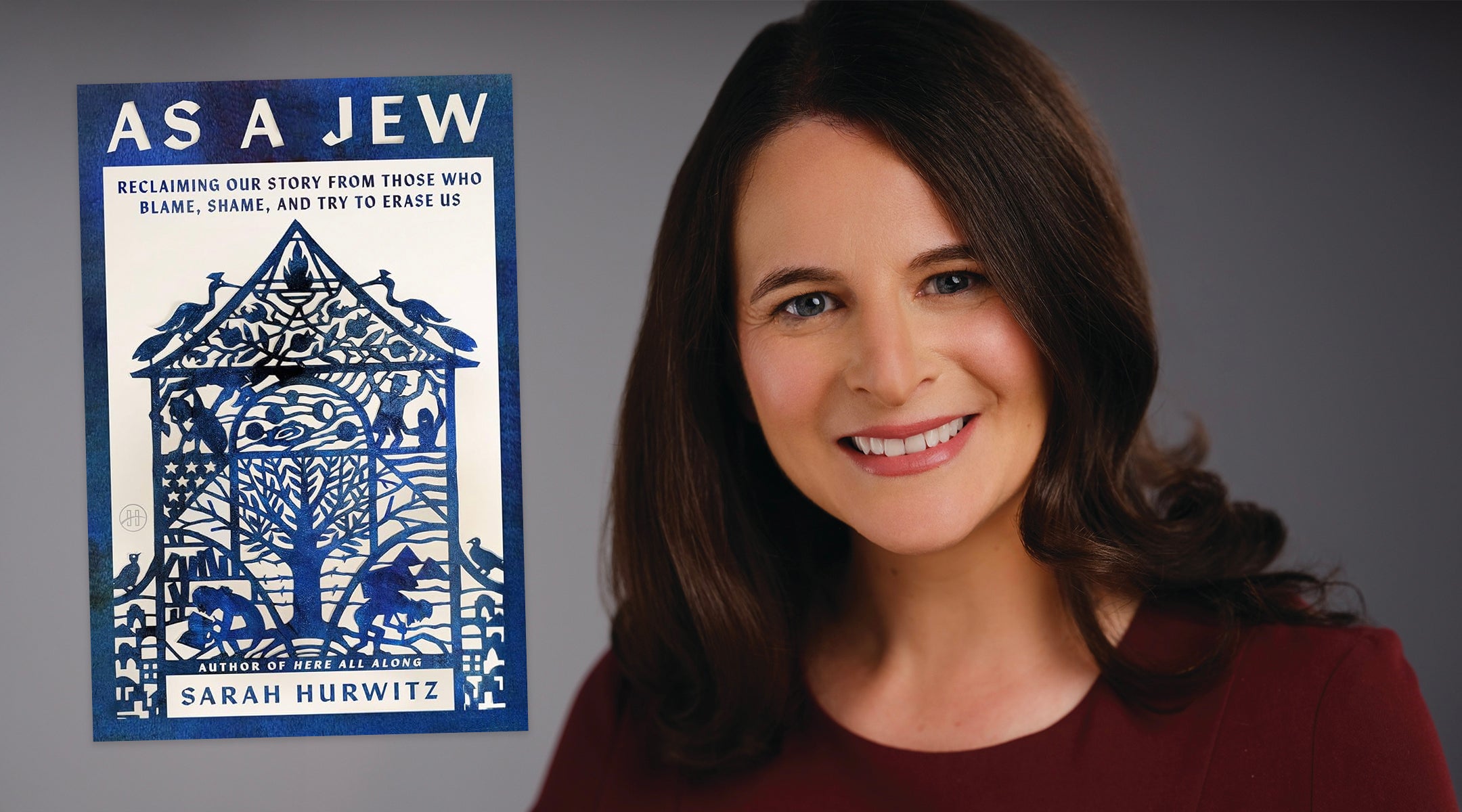

Sarah Hurwitz calls her first book, “Here All Along,” a “love letter” to Jewish tradition. Describing a journey begun when she worked as a speechwriter at the White House— first for President Barack Obama and later for First Lady Michele Obama — the book was a celebration of her rediscovering Judaism as a thirty-something who grew up with what she describes as a “thin” Jewish identity.

But if that book was sunny, her new book explores the shadows and storm clouds of Jewish belonging. “As a Jew: Reclaiming Our Story from Those Who Blame, Shame, and Try to Erase Us,” confronts the challenges of being Jewish at a time of rising antisemitism, a polarizing debate over Israel, and pressures and temptations that keep many Jews from appreciating a tradition that belongs to them.

Shifting the focus from personal discovery to a host of contemporary issues, “As a Jew” is both a primer and a polemic, explaining Jewish history, texts and practices in order to counter misinformation and inspire readers.

“We need to know our story. We need to know our history. We need to know our traditions,” she said in an interview on Thursday. “We need to know what we love about being Jews, so that when people come to us and they say, ‘Judaism is violent and vengeful and sexist and has a cruel God and is unspiritual,’ we can say that’s not true.”

The book also draws on her recent training and experience as a hospital chaplain, volunteering on the oncology floor of a hospital in the Washington, D.C. area, where she lives.

Hurwitz, 44, is a graduate of Harvard University and Harvard Law School. She also served as a speechwriter for Vice President Al Gore and in Hillary Clinton’s 2008 presidential campaign. In January, she plans to start training for the rabbinate at the Shalom Hartman Institute’s Beit Midrash for New North American Rabbis.

We spoke at a livestreamed “Folio” event presented by the New York Jewish Week and UJA-Federation of New York. Hurwitz discussed her time in the Obama White House, what she’s learned from meeting with college students struggling with antisemitism, and the challenges of writing a Jewish book in the post-Oct. 7 moment.

Our conversation was edited for length and clarity. To watch the full conversation, go here.

Your first book, “Here All Along,” was about your return to Jewish learning. What hadn’t you said in that first book that you felt compelled to say now? And how does “As a Jew” extend or challenge the earlier journey?

My first very much a love letter to Jewish tradition, and this book is much more of a polemic. That first book really reflected me at the age of 36 rediscovering Jewish tradition, having grown up with this very thin kind of Jewish identity.

In this new book, I began to really ask the question, why did I see so little of Jewish tradition growing up, why did I have to wait until age 36 to actually discover so much of our tradition? Why was my identity so apologetic, so kind of humiliating and, having grown up in a Christian country, how much of my approach to Judaism was really through a Christian lens? This book really dives into those questions at a time of rising antisemitism, where Jews need to start thinking about these things.

What does it mean to be apologetic? How did the Christian lens distort your understanding of Judaism?

I certainly believed that Christianity is a religion of love, but Judaism is really a religion of law. And I really did buy that, that ours is a kind of weedy, legalistic, nitpicky tradition with this angry, vengeful god. I mean, that is just classic Christian anti-Judaism. I also used to think this world is carnal, degraded, inferior, kind of gross, and the goal of spirituality was to transcend them. That is not a central Jewish idea at all. That is not what Jewish spirituality is. If you read the Torah, our core sacred text, you’re going to find a great deal about our bodies, but how we treat them, about really contemplating how they are quite sacred.

Sarah Hurwitz (left), a former speechwriter for First Lady Michelle Obama, does a “gazing exercise” with rabbinical student Lily Solochek at Romemu Yeshiva in New York, N.Y. on July 16, 2019. (Ben Sales)

You say more than once in your book that you want to “take back the Jewish story.” What does it mean to take back the Jewish story, and from whom or what?

Our story has often been told by others, and you actually see this in this very old story about Jewish power, depravity and conspiracy. You see it in the core story about a group of Jews conspiring to kill Jesus. And you see these themes winding their way through history. That story has been told about Jews for centuries. I want to replace it with our actual story, as told through Jewish texts and traditions.

The alternative you propose, in order for Jews to embrace their own story, is that they embrace the “textline,” which you call “the repository of our Jewish memory, the raw material for the story we tell about who we are.” I am not familiar with “textline” — how does it differ from “text”?

This is actually from [the late Israeli novelist] Amos Oz, and his daughter, historian Fania Oz-Salzberger. They say, “Ours is not a bloodline, it’s a textline.” Jews are racially and ethnically diverse, but our shared DNA, the thing that unites us, is our texts. Sadly, in the early 1800s, as Jews gained citizenship in Europe, there was a decision to assimilate and reshape Judaism to look more like Protestantism — a kind of “Jewish church.” In doing so, we de-emphasized 2,500 years of textual tradition beyond the Torah, which is where much of Jewish wisdom and ritual is found. Reclaiming that textual tradition is critical.

The idea and dilemmas of Jewish power is a theme in your book and incredibly timely, given the debate over Israel’s display of power in Gaza and several other fronts. How does your book approach the moral and spiritual tension of Jews moving from centuries of powerlessness to now having power and a state?

Many Jews today feel distress over the responsibility that comes with power. For 2,000 years, Jews were powerless, blameless victims. The problem with statelessness was that it led to slaughter on a massive scale. Some yearn for that innocence of powerless Jewish life, but I disagree that the cost of millions of deaths was worth it. With power comes moral responsibility. Israel, like all nations, is conceived and maintained in violence. I see the moral complexity, but I do not want to give up the power or the responsibility that comes with it.

After your first book came out, you became a prominent voice in Jewish life. Can you share encounters on the road that shaped your thinking for this book?

First, training as a volunteer hospital chaplain helped me realize the profound, Jewish-centered human experience of accompanying people in moments of illness, grief and death. Second, visiting universities before Oct. 7, 2023, I was stunned by Jewish students asking how I dealt with antisemitism in college. When I said I hadn’t experienced any, the students were shocked. Post-2023, the Gaza war accelerated ugly narratives on social media, which deeply worried me. I also reflected on my first book and realized that the Judaism I grew up with was oddly edited, shaped by our ancestors’ attempts to assimilate for safety — a choice I deeply respect but which left us somewhat “textless.”

How do your chaplaincy experiences relate text to real life?

I volunteer in D.C. hospitals. Being present with people in illness, grief and death is profoundly Jewish. Modern society finds these experiences uncomfortable, but Jewish tradition calls us to accompany mourners, prepare the dead lovingly, and inhabit the thin spaces where life and death blur. This presence, grounded in community, is essential. People often find relief simply in having someone acknowledge reality and speak openly about it.

You started writing this book before Oct. 7. How did the Hamas attacks and the Gaza war influence your writing about peoplehood, empathy and responsibility?

Oct. 7 didn’t change the arguments or themes of my book, but it gave more data points. For decades, Jews in America and Israel lived somewhat disconnected lives. Oct. 7 revealed underlying tensions and reminded us that Jewish identity has always carried conditionality. Some had illusions about a “golden age” of safety in the 1980s and 1990s, but many had faced real threats. The attacks shattered any illusions of security and exposed deeper societal challenges.

You talk about students on campuses being excluded from college clubs and causes because they are Zionist. I found your response intriguing — that Jews again create their own institutions the way they created Jewish hospitals and universities in the early part of the 20th century as a response to exclusion. Do you worry that you are overreacting?

Campuses vary widely. Some departments are excellent; some are hostile. In difficult environments, I advise Jewish students to try dialogue, but if excluded, to create their own spaces — clubs, organizations and initiatives, that are radically inclusive and excellent. Historically, Jews created hospitals, law firms and universities that welcomed anyone committed to excellence and tolerant of Jews. We can do that again. For example, Allison Tombros Korman founded the Red Tent after being ostracized [in the reproductive rights space] for her Zionist beliefs. It funds abortion services for anyone and is inclusive — an inspiring model.

Your book includes a chapter on Israel that aims to counter the accusations that Zionism is colonialist and racist. But you also include criticism of Israel, saying the country is not without its “serious flaws.” How do you navigate the lonely place of being a liberal Zionist today, which I often define as being too Zionist for the liberals and too liberal for many Zionists?

I navigate it like I navigate being an American: I can criticize, feel frustrated and yet remain committed. Israel is the home of 7 million Jewish siblings. Criticism does not mean abandonment. Many confuse ideology with family obligation, but Israel is our family, and we must stand with it while lovingly correcting its errors. This mirrors my commitment to America.

You were active in a Democratic administration and no doubt have seen the evidence of decreasing support for Israel among Democrats. Was that your experience when you worked in the Obama administration? Is that something you had to push back against?

I think people are a little bit confused about when the Obama administration ended, which was 2017. That was well before this 2023 dark turn, you know, it was a pretty normie administration. I don’t remember a single time in the Obama administration where anything negative was said about Israel. It was a great administration to be a Jew. I started first exploring Judaism when I was working in the White House, and my colleagues were so overwhelmingly proud of me, I could not just [believe] the encouragement they gave me. One time I actually ran into the White House chief of staff, a wonderful guy named Denis McDonough, and he asked me what I was doing for the December vacation, and the answer was, I was going to a weeklong silent Jewish meditation retreat. You don’t tell the chief of staff that you’re doing that, but I did, because I didn’t want to lie, and he just could not have been more proud.

Sarah Hurwitz interviewed by Norwegian actor Hans Olav Brenner in 2017, under a photo of her and President Barack Obama during her time as one of his speechwriters. (Thor Brødreskift/Nordiske Mediedager)

I now see, unfortunately, an ideology that’s been on the fringes of the left slowly making its way to the mainstream, and that worries me. I don’t think it is outrageous for Democrats to withhold an occasional shipment of weapons to express displeasure with Israel’s policy, but what worries me is that we are in a bigger environment of a real demonization and delegitimization of Israel.

I’m also really worried about the right. If you look at the data, especially among young men, they’re increasingly antisemitic, increasingly anti-Israel. And what I particularly worry about is that I see President Trump under the guise of fighting antisemitism on campus, engaging in really heavy-handed efforts to defund university campuses. And you can celebrate that. You can say it’s good for Jews, but I disagree, and I also worry about the precedent, that five or 10 years from now, when there is a president with a very different political ideology, who says that “Israel is a terrorist country, Zionism is a terrorist ideology, and I’m going to go and defund every campus that has an active Hillel, because Hillel is a Zionist entity.” We’ve paved that illiberal path, and it’s very easy for someone on the other side to walk down it.

I also really worry about, on the right, the MAGA ideology that says that a small group of powerful, depraved elites is conspiring to harm you and your family, to vaccinate you, to make your kids trans. It’s a very ugly ideology that is the very structure of antisemitism. The leap between elites and Jews is about a centimeter and Tucker Carlson’s made the leap. It’s got millions of followers. A lot of other people are making the leap.

Your books are, as you’ve said, love letters to Jewish tradition. But often observant Jews, here and in Israel, who are deeply steeped in Jewish text and practice, also embrace views that are illiberal and ultra-nationalist. How do you reconcile their embrace of the “textline,” and the illiberal positions they arrive at?

You are talking about the extremists, like [Bezalel Smotrich and Itamar Ben-Gvir, two far-right Israeli cabinet ministers]. I think they are being quite unfaithful to Jewish tradition. Judaism operates in polarities, holding opposing truths: love the stranger yet remember Amalek; humility and self-esteem; compassion with caution. Extremists claim only one pole, but both are essential. Jewish tradition demands wrestling with these tensions.

And yet those tensions are straining communal ties. How do Jews remain responsible for one another when there are such deep disagreements?

Judaism emphasizes the ethic of family. Even if family members espouse objectionable views, we engage them with tochecha — loving, private rebuke — to correct and guide them. Boundaries must exist for safety, but generally, we strive to keep people at the table, engage with them, and educate them.

A lot of Jewish authors are finding that it is difficult since Oct. 7 to promote their books, especially when they lean heavily into Jewish or Israeli content. How are you being received, having written a Jewish book in this time and place?

I only do events in Jewish institutions with a very small number of exceptions, so I haven’t been in any bookstores. I’m not really interested in going to bookstores. I want to go to places that have, frankly, good security and where it will be more than 20 people. I will say I’ve been surprised at how little pushback I’ve gotten to my book, because I thought this was a pretty edgy book. You know, I think my first book was pretty soft — like, “yay Judaism!” The second book is a polemic, and I was worried that I would get real pushback, real criticism, real anger. And yet, from the Jewish world, I’ve had Jewish leaders who are more on the right-wing side of the spectrum politically who like it, and leaders who are on the left-wing part of the spectrum who like it. They’ll tell me, “I see your compassion, and I see that you’re really wrestling with the other side, with those who disagree with you.”

Is there a Jewish text that you kind of live by, or that you really love, or just came across yesterday that really spoke to you this week or in this hour?

There’s so many, but I’ll take one. I’ll just simplify it. In [the Babylonian Talmud, Brachot 5b,] Rabbi A gets sick and then Rabbi B shows up and takes his hands and heals him. But then Rabbi B himself gets sick and Rabbi C shows up and takes Rabbi B’s hand and heals him. And the rabbis studying the story are very confused, because if Rabbi B, who was kind of known as a healer, could heal Rabbi A, then when he got sick himself, why didn’t he just cure himself? Why did he need Rabbi C to come and cure him?

And the answer that they offer is because “the prisoner cannot get himself out of prison.” I just think that’s a really beautiful story about the ways that we become trapped in our own anxiety, fear, anger, loneliness and really do need other people to come and take our hand and kind of pull us out. I thought about this a lot while writing my book. There’s about 80 people in my acknowledgements who read part or all of this book. And that was very important, because as a writer, I cannot get myself out of the prison of my own biases, my own ignorance, my own narrow views, and so many people reached out, took my hand and said, “What you’re writing is wrong,” or “that’s offensive,” or “you don’t know what you’re talking about.” And they said it very nicely. It was so important to me because I could actually step out and learn.

So I love that story. I think it illustrates something profound about what it means to be human.

—

The post Sarah Hurwitz wants Jews to stop apologizing and start learning appeared first on Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

Uncategorized

BBC Apologizes for Not Mentioning Jews During Holocaust Remembrance Day Coverage

The BBC logo is displayed above the entrance to the BBC headquarters in London, Britain, July 10, 2023. Photo: REUTERS/Hollie Adams

The BBC apologized on Tuesday night after at least four of its presenters failed to mention the murder of Jews in the Holocaust during the national broadcaster’s coverage of International Holocaust Remembrance Day.

“BBC Breakfast” presenter Jon Kay said on air Tuesday morning that Holocaust Remembrance Day was “for remembering the six million people murdered by the Nazi regime over 80 years ago.” Several BBC broadcasts by some of its most well-known presenters included similar comments that omitted the mention of Jewish victims when discussing the Holocaust.

In one broadcast, “BBC News” presenter Martine Croxall also said Holocaust Remembrance Day is a day “for remembering the six million people who were murdered by the Nazi regime over 80 years ago.”

BBC World News presenter Matthew Amroliwala introduced a bulletin on his show with the same scripted line.

On the BBC Radio 4 program “Today,” presenter Caroline Nicholls discussed plans to mark Holocaust Remembrance Day and said in part: “Buildings across the UK will be illuminated this evening to mark Holocaust Memorial Day, which commemorates the six million people murdered by the Nazi regime more than 80 years ago.”

“Is the BBC trying to sever all ties with their Jewish listeners? Even on Holocaust Memorial Day, the BBC cannot bring itself to properly address antisemitism,” the Campaign Against Antisemitism posted on X. “This is absolutely disgraceful broadcasting. BBC, we demand an explanation for how this could have happened.”

“The ‘Today’ program featured interviews with relatives of Holocaust survivors, and a report from our religion editor. In both of these items we referenced the six million Jews murdered during the Holocaust,” the statement read in part, as cited by GB News. “‘BBC Breakfast’ featured a project organized by the Holocaust Educational Trust in which a Jewish survivor of the Holocaust recorded her memories. In the news bulletins on ‘Today’ and in the introduction to the story on ‘BBC Breakfast’ there were references to Holocaust Memorial Day which were incorrectly worded, and for which we apologize. Both should have referred to ‘six million Jewish people’ and we will be issuing a correction on our website.”

Karen Pollock, chief executive of the Holocaust Educational Trust, said in a post on X that the BBC’s not mentioning Jews during its coverage of Holocaust Remembrance Day is “hurtful, disrespectful, and wrong.”

“The Holocaust was the murder of six million Jewish men, women, and children. Any attempt to dilute the Holocaust, strip it of its Jewish specificity, or compare it to contemporary events is unacceptable on any day,” she added.

Danny Cohen, the BBC’s former director of television, said the mistake, especially on Holocaust Remembrance Day, “marks a new low point” for the broadcaster. He said the mishap will surely be hurtful to many in the Jewish community “and will reinforce their view that the BBC is insensitive to the concerns of British Jews.”

“It is surely the bare minimum to expect the BBC to correctly identify that it was six million Jews killed during the Holocaust,” said Cohen, as cited by the Daily Mail. “To say anything else is an insult to their memory and plays into the hands of extremists who have desperately sought to rewrite the historical truth of history’s greatest crime.”

This year’s Holocaust Remembrance Day marks the 81st anniversary of the liberation of the Auschwitz-Birkenau Nazi concentration camp in 1945. On Tuesday, King Charles and the Queen Camilla lit candles at Buckingham Palace in honor of the annual commemoration and hosted a reception for Holocaust survivors and their families. Last year, King Charles, who is patron of the Holocaust Memorial Day Trust, became the first British monarch to visit Auschwitz on the 80th anniversary of its liberation.

Tuesday was not the first time that the BBC has come under fire for its coverage of issues concerning the Jewish community or Israel.

In February 2025, the BBC apologized for “unacceptable” and “serious flaws” in its documentary about Palestinian children living in the Gaza Strip, after it was revealed that the documentary’s narrator was the son of a senior Hamas official. An internal review by the British public broadcaster also revealed that the documentary breached the BBC’s editorial guidelines on accuracy.

In July, the BBC apologized for streaming a live performance by the British punk rap duo Bob Vylan at the Glastonbury Festival, during which the band’s lead singer led the audience in chanting “Death to the IDF,” referring to the Israel Defense Forces.

Also last year, the host of “Good Morning Britain” apologized on-air for failing to mention Jewish victims of the Holocaust during her coverage of International Holocaust Remembrance Day.

Uncategorized

New York Is Right to Keep Antisemitic Protests Away From Synagogues

Nov. 19, 2025, New York, New York, USA: Anti-Israel protesters rally outside of Park East Synagogue. Photo: ZUMA Press Wire via Reuters Connect

Hamas’ October 7 massacre, and the subsequent war against Israel, motivated sympathizers of the terrorist group to persecute Jews worldwide, even though the practice of blaming Jews for the actions of Israel is a globally recognized form of antisemitism.

In the US, dozens of these antisemitic campaigns targeted synagogues.

In recent months, the bigoted rallies grew especially menacing at two New York synagogues that hosted events for a non-profit corporation called Nefesh B’Nefesh (NBN). NBN conducts information fairs that promote “aliyah” (immigration) to Israel, and it guides interested parties through the naturalization process.

During the NBN gatherings, congregants could not enter or exit the synagogues without encountering harassment and intimidation by hundreds of angry demonstrators.

The haters obstructed the entrances while screaming antisemitic obscenities and incitements such as “Intifada revolution” and “Resistance you make us proud; take another settler out.” At one of the synagogues, the protestors endorsed antisemitic terrorism by chanting, “Say it loud, say it clear, we support Hamas here.” Meanwhile, a member of the crowd repeatedly shouted, “We need to make them scared.”

On January 13, 2026, New York Governor Kathy Hochul (D) pledged to curb such synagogue-focused hostility by legislating protest-free buffer zones for all houses of worship. Each buffer zone would form a 25-foot perimeter around the property of the religious institution. Outside the boundary, demonstrators could freely exercise their First Amendment right to scream and shout. Inside the line, worshipers could safely enter and exit the facility, engage in their freedoms of speech and religion, and enjoy their right of privacy to avoid the rowdy mob.

Pro-Palestinian organizations oppose the New York buffer zone proposal. The advocates claim that NBN illegally sells “stolen” Palestinian land. In their view, the slated law would not only “censor” their free speech right to denounce the alleged NBN crimes, but make New York State “complicit” in the supposed wrongdoing. They call the information fairs “non-religious political events.”

New York City Mayor Zohran Mamdani (D), who is openly pro-Palestinian, remains noncommittal on the buffer zone scheme. But he opposes NBN, arguing that “sacred spaces” should not be used to breach international law.

The mayor and buffer zone opponents misconstrue the applicable law. The 1994 Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances (FACE) Act prohibits close-range harassment, intimidation, and physical interference at houses of worship, as well as reproductive health clinics.

Within this Federal framework, states and municipalities have enacted buffer zones to separate potentially dangerous protestors from those who frequent the protected sites. The Supreme Court has upheld the use of buffer zones to balance the adversarial rights involved. Based on subsequent case law, a thin, 25-foot buffer zone, such as the one designed for New York, is valid because it is “narrowly tailored” to meet its Constitutional goals.

Demonstration organizers cannot credibly portray NBN presentations as non-religious political events. In Judaism, “making aliyah” means “going up” to settle in the Biblical Promised Land. The ascent is a religious rite that Jews have performed for millennia. That is why NBN extends its outreach to synagogues. Even if NBN’s operations were purely political, they would deserve just as much First Amendment protection as any religious affair.

Another misconception is that NBN sells land. In reality, the outfit merely provides guidance on how to find housing.

The broader accusation that Israel illegally builds settlements on occupied Palestinian land is also untrue. The territories claimed by Palestinians have already been lawfully allocated to the state that became Israel, pursuant to the 1920 San Remo Treaty and 1922 British Mandate for Palestine. Occupation law applies when a state captures foreign land, but not when it settles its own land. A temporary exception to Israel’s sovereign reach was established when Israel and the Palestinians negotiated interim spheres of territorial control — called “Areas A, B and C” — in the Oslo Accords of the 1990s. Those limits are strictly observed by Israelis.

The International Court of Justice ruling referenced by the protest partisans to claim NBN is selling or promoting settlement on stolen land was an “advisory opinion,” which means it had no legally binding effect. It’s just as well. A dissenting judge on the court rightly rebuked the decision for failing to recognize Israel’s territorial rights. The US government recognizes Israel’s territorial rights. Any buffer zone objectors who dispute that US position should lobby the Trump administration, not Governor Hochul, because the Constitution reserves matters of international relations exclusively for the Federal government.

Regardless of whether Israeli settlements comply with international law, nothing in that legal realm can supersede the Constitutional safeguards planned for New York’s synagogues. The US government is legally barred from accepting any international obligation inconsistent with the Constitution.

The current trend of unbridled antisemitism has trampled on Jewish civil rights. Some of the worst offenders are those who harass Jews at the entrances to their synagogues. A buffer zone is the bare minimum needed to keep that threat at bay.

Joel M. Margolis is the legal commentator of the American Association of Jewish Lawyers and Jurists, the US affiliate of the International Association of Jewish Lawyers and Jurists.

Uncategorized

‘Time Is Running Out’: Trump Warns Iran to Make a Deal or Next Attack Will Be ‘Far Worse’

US President Donald Trump delivers a speech on energy and the economy, in Clive, Iowa, US, Jan. 27, 2026. Photo: REUTERS/Kevin Lamarque

US President Donald Trump urged Iran on Wednesday to come to the table and make a deal on nuclear weapons or the next US attack would be far worse, but Tehran said that if that happened it would fight back as never before.

“Hopefully Iran will quickly ‘Come to the Table’ and negotiate a fair and equitable deal – NO NUCLEAR WEAPONS – one that is good for all parties. Time is running out, it is truly of the essence!” Trump wrote in a social media post.

The Republican US president, who pulled out of world powers’ 2015 nuclear deal with Tehran during his first White House term, noted that his last warning to Iran was followed by a military strike in June.

“As I told Iran once before, MAKE A DEAL! They didn’t, and there was ‘Operation Midnight Hammer,’ a major destruction of Iran,” Trump continued. “The next attack will be far worse! Don’t make that happen again.”

He also repeated that a US “armada” was heading toward the Islamic Republic.

Iran‘s mission to the United Nations responded in kind.

“Last time the US blundered into wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, it squandered over $7 trillion and lost more than 7,000 American lives,” it said in an X post quoting Trump‘s statement.

“Iran stands ready for dialogue based on mutual respect and interests—BUT IF PUSHED, IT WILL DEFEND ITSELF AND RESPOND LIKE NEVER BEFORE!”

Iranian Foreign Minister Abbas Araqchi said he had not been in contact with US special envoy Steve Witkoff in recent days or requested negotiations, state media reported on Wednesday.

“There was no contact between me and Witkoff in recent days and no request for negotiations was made from us,” Araqchi told state media, adding that various intermediaries were “holding consultations” and were in contact with Tehran.

“Our stance is clear, negotiations don’t go along with threats and talks can only take place when there are no longer menaces and excessive demands.”

Trump said a US naval force headed by the aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln was approaching Iran. Two US officials told Reuters on Monday that the Lincoln and supporting warships had arrived in the Middle East.

The warships started moving from the Asia-Pacific region last week as US-Iranian tensions soared following a bloody crackdown on anti-government protests across Iran by its clerical authorities in recent weeks.

Trump has repeatedly threatened to intervene if Iran continued to kill protesters, but the countrywide demonstrations over economic privations and political repression have since abated. According to reports, the Iranian regime may have killed more than 30,000 people over two days in one of the deadliest crackdowns in modern history.

He has said the United States would act if Tehran resumed its nuclear program after the June airstrikes by Israeli and US forces on key nuclear installations.

Iran‘s President Masoud Pezeshkian told Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman in a phone call on Tuesday that Tehran welcomes any process, within the framework of international law, that prevents war.

Bin Salman said during the conversation that Riyadh will not allow its airspace or territory to be used for military actions against Tehran, state news agency SPA reported on Tuesday.

The statement by the Saudi de facto ruler follows a similar statement by the United Arab Emirates that it would not allow any military action against Iran using its airspace or territorial waters.