Uncategorized

Prominent Orthodox politician swaps endorsement of Republican for Cuomo as NYC mayoral election nears

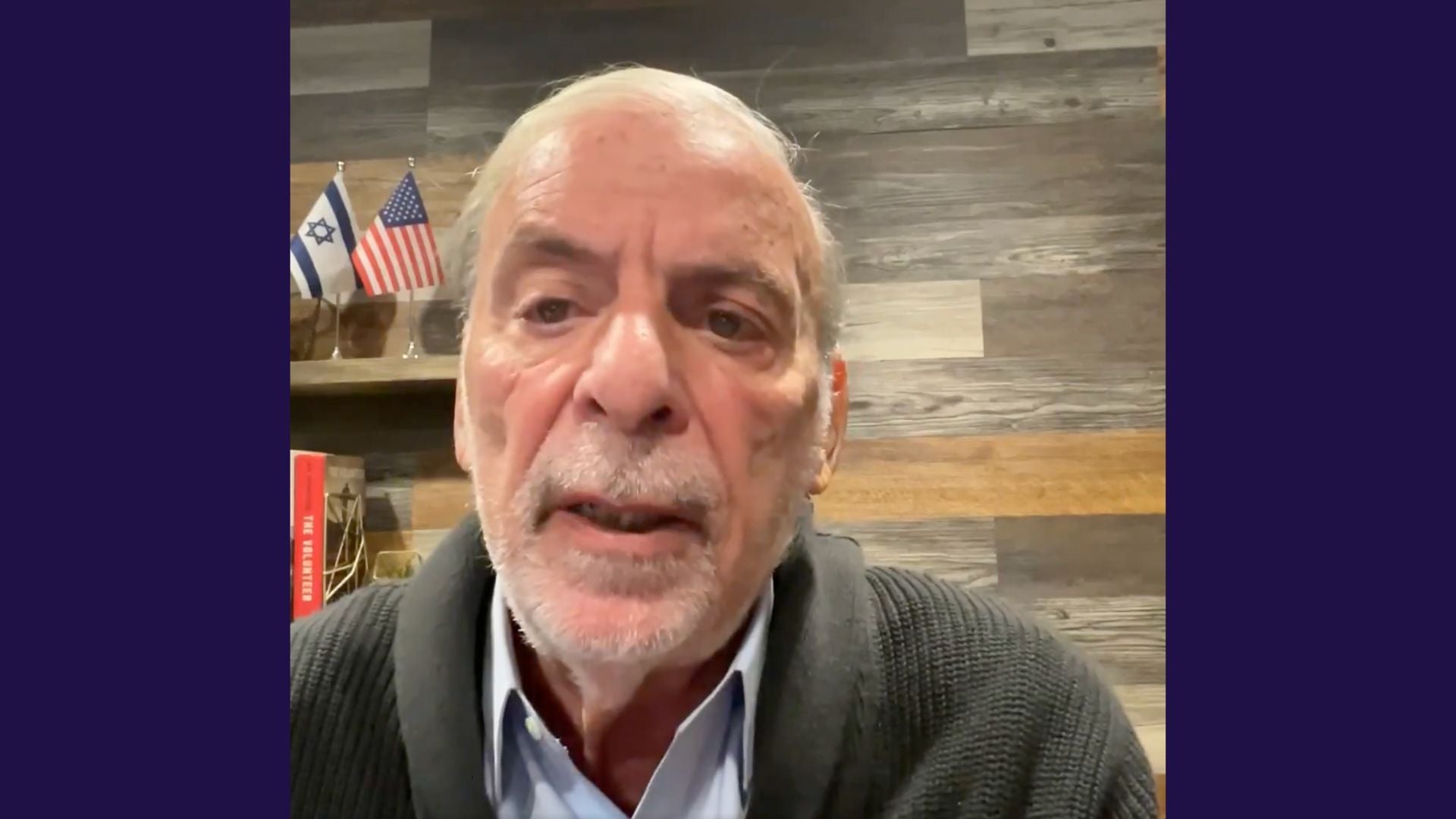

Curtis Sliwa has long pointed to Dov Hikind, a former New York state assemblyman who represented Jewish neighborhoods in Brooklyn for more than three decades, as one of strongest allies within the New York Jewish community.

Last month, in an interview with the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, Sliwa named Hikind, who also founded the nonprofit Americans Against Antisemitism, as a key Jewish figure in his circle. The pair also canvassed together during Rosh Hashanah.

“Without a doubt, the man that I’ve been through so many struggles over the years is Dov Hikind,” said Sliwa. “He knows everyone, and he is completely in support of me because he knows, whenever Jews have been in need, he says, ‘Curtis was always there.’”

But on Sunday, as early voting started in the election, Hikind dropped his support for Sliwa. Instead, he urged New Yorkers to vote for former Gov. Andrew Cuomo in a last-ditch effort to halt frontrunner Zohran Mamdani’s march to City Hall.

“As difficult as it is for me to post this video, I must face the reality as I see it,” Hikind said in a message posted to social media. “I endorsed Curtis Sliwa and while I never thought I’d say this, I am now asking that you vote for Andrew Cuomo. Why? Because if Mamdani wins, the very future of New York City is at stake.”

He added, “You don’t have to love Cuomo. I’ve been clear about how I feel about him. This election though isn’t about who we like. It’s about saving New York City from Mamdani.”

Hikind’s flip-flop comes as Jewish advocates increasingly urge voters to back Cuomo as a way to consolidate opposition to Mamdani, a democratic socialist who is staunchly critical of Israel. With Mamdani posting a double-digit lead over Cuomo in polls, and Sliwa is tailing third in the race, some Jewish voices are intensifying efforts to persuade Sliwa to drop out and back Cuomo. That includes in Hikind’s region of Brooklyn, where the exit last month of Mayor Eric Adams from the race caused some Jewish leaders who had not committed to a candidate to back Cuomo.

Hikind has indeed long criticized Cuomo for his handling of the COVID-19 pandemic and the sexual harassment allegations against him in 2021 that led to his resignation.

“I believe that the person that is best for the people of New York is Curtis Sliwa,” said Hikind during a Fox News interview posted by Sliwa on Instagram earlier this month. “We have Cuomo, who was governor of the state of New York, and quit. He decided to quit because of things that he was involved in, the inappropriate behavior with so many women, and let’s not forget, Cuomo is responsible for 1000s and 1000s of senior citizens being sent to nursing homes during COVID.”

In 2020, Hikind published a book trolling Cuomo’s decisions during the pandemic titled “Lessons in ‘Leadership,’” that included a foreword lambasting “King Covidius Cuomo” followed by 100 pages of blank white paper.

Now, he said in his new post, he had no choice but to vote for Cuomo. “We do not have the luxury of misplacing our votes. I like Curtis. I still think he’d be a great mayor, but right now, there’s only one person who can stop Mamdani, and that’s Andrew Cuomo,” he said. “You don’t have to love him. You don’t have to like him. You just have to save New York City. So I urge you to vote for Cuomo.”

—

The post Prominent Orthodox politician swaps endorsement of Republican for Cuomo as NYC mayoral election nears appeared first on Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

Uncategorized

21 Arab, Islamic, African States and Entities Condemn Israel’s Recognition of Somaliland

The signatories’ flags enclosed in the statement in Arabic. Photo: Screenshot via i24.

i24 News – A group of 21 Arab, Islamic and African countries, organizations and entities issued on Saturday a joint statement condemning Israel’s recognition of Somaliland sovereignty.

The statement’s signatories said that they condemn and reject Israel’s recognition of Somaliland “in light of the serious repercussions to peace and security in the Horn of Africa and the Red Sea region, and its serious impacts on international peace and security, which also reflects Israel’s clear and complete disregard for international law.”

It was signed by: Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Turkey, Iran, Pakistan, Qatar, Jordan, Algeria, Iraq, Kuwait, Oman, Libya, Palestine, Somalia, Sudan, Yemen, Comoros, Djibouti, Gambia, Maldives, Nigeria and the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC).

The joint statement voiced support “for the sovereignty of Somalia and reject any measures that would undermine its unity, territorial integrity, and sovereignty over all its lands.”

The signatories also “categorically reject linking Israel’s recognition of the territory of the land of Somalia with any plans to displace the Palestinian people outside their land.”

Uncategorized

Nvidia, Joining Big Tech Deal Spree, to License Groq Technology, Hire Executives

A NVIDIA logo appears in this illustration taken Aug. 25, 2025. Photo: REUTERS/Dado Ruvic/Illustration

Nvidia has agreed to license chip technology from startup Groq and hire away its CEO, a veteran of Alphabet’s Google, Groq said in a blog post on Wednesday.

The deal follows a familiar pattern in recent years where the world’s biggest technology firms pay large sums in deals with promising startups to take their technology and talent but stop short of formally acquiring the target.

Groq specializes in what is known as inference, where artificial intelligence models that have already been trained respond to requests from users. While Nvidia dominates the market for training AI models, it faces much more competition in inference, where traditional rivals such as Advanced Micro Devices have aimed to challenge it as well as startups such as Groq and Cerebras Systems.

Nvidia has agreed to a “non-exclusive” license to Groq’s technology, Groq said. It said its founder Jonathan Ross, who helped Google start its AI chip program, as well as Groq President Sunny Madra and other members of its engineering team, will join Nvidia.

A person close to Nvidia confirmed the licensing agreement.

Groq did not disclose financial details of the deal. CNBC reported that Nvidia had agreed to acquire Groq for $20 billion in cash, but neither Nvidia nor Groq commented on the report. Groq said in its blog post that it will continue to operate as an independent company with Simon Edwards as CEO and that its cloud business will continue operating.

In similar recent deals, Microsoft’s top AI executive came through a $650 million deal with a startup that was billed as a licensing fee, and Meta spent $15 billion to hire Scale AI’s CEO without acquiring the entire firm. Amazon hired away founders from Adept AI, and Nvidia did a similar deal this year. The deals have faced scrutiny by regulators, though none has yet been unwound.

“Antitrust would seem to be the primary risk here, though structuring the deal as a non-exclusive license may keep the fiction of competition alive (even as Groq’s leadership and, we would presume, technical talent move over to Nvidia),” Bernstein analyst Stacy Rasgon wrote in a note to clients on Wednesday after Groq’s announcement. And Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang’s “relationship with the Trump administration appears among the strongest of the key US tech companies.”

Groq more than doubled its valuation to $6.9 billion from $2.8 billion in August last year, following a $750 million funding round in September.

Groq is one of a number of upstarts that do not use external high-bandwidth memory chips, freeing them from the memory crunch affecting the global chip industry. The approach, which uses a form of on-chip memory called SRAM, helps speed up interactions with chatbots and other AI models but also limits the size of the model that can be served.

Groq’s primary rival in the approach is Cerebras Systems, which Reuters this month reported plans to go public as soon as next year. Groq and Cerebras have signed large deals in the Middle East.

Nvidia’s Huang spent much of his biggest keynote speech of 2025 arguing that Nvidia would be able to maintain its lead as AI markets shift from training to inference.

Uncategorized

Russian Drones, Missiles Pound Ukraine Ahead of Zelensky-Trump Meeting

Rescuers work at the site of the apartment building hit by a Russian drone during a Russian missile and drone strike, amid Russia’s attack on Ukraine, in Kyiv, Ukraine December 27, 2025. REUTERS/Viacheslav Ratynskyi

Russia attacked Kyiv and other parts of Ukraine with hundreds of missiles and drones on Saturday, ahead of what President Volodymyr Zelensky said would be a crucial meeting with US President Donald Trump to work out a plan to end nearly four years of war.

Zelensky cast the vast overnight attack, which he said involved about 500 drones and 40 missiles and which knocked out power and heat in parts of the capital, as Russia’s response to the ongoing peace efforts brokered by Washington.

The Ukrainian leader has said Sunday’s talks in Florida would focus on security guarantees and territorial control once fighting ends in Europe’s deadliest conflict since World War Two, started by Russia’s 2022 invasion of its smaller neighbor.

The attack continued throughout the morning, with a nearly 10-hour air raid alert for the capital. Authorities said two people were killed in Kyiv and the surrounding region, while at least 46 people were wounded, including two children.

“Today, Russia demonstrated how it responds to peaceful negotiations between Ukraine and the United States to end Russia’s war against Ukraine,” Zelensky told reporters.

In Russia, air defense forces shot down eight drones headed for Moscow, the city’s mayor Sergei Sobyanin said on Saturday.

THOUSANDS OF HOMES WITHOUT HEAT

Explosions echoed across Kyiv from the early hours on Saturday as Ukraine’s air defense units went into action. The air force said Russian drones were targeting the capital and regions in the northeast and south.

State grid operator Ukrenergo said energy facilities across Ukraine were struck, and emergency power cuts had been implemented across the capital.

DTEK, Ukraine’s largest private energy company, said the attack had left more than a million households in and around Kyiv without power, 750,000 of which remained disconnected by the afternoon.

Deputy Prime Minister Oleksiy Kuleba said over 40% of residential buildings in Kyiv were left without heat as temperatures hovered around 0 degrees Celsius (32 degrees Fahrenheit) on Saturday.

TERRITORIAL CONTROL: A DIPLOMATIC STUMBLING BLOCK

On the way to meeting Trump in Florida, Zelensky stopped in Canada’s Halifax to meet Prime Minister Mark Carney, after which they planned to hold a call with European leaders.

In a brief statement with Zelenskiy by his side, Carney noted that peace “requires a willing Russia.”

“The barbarism that we saw overnight — the attack on Kyiv — shows just how important it is that we stand with Ukraine in this difficult time,” he said, announcing 2.5 billion Canadian dollars ($1.83 billion) in additional economic aid to Ukraine.

Territory and the future of the Russian-occupied Zaporizhzhia nuclear plant remain the main diplomatic stumbling blocks, though Zelensky told journalists in Kyiv on Friday that a 20-point draft document – the cornerstone of a US push to clinch a peace deal – is 90% complete.

He said the shape of U.S. security guarantees was crucial, and these would depend on Trump, and “what he is ready to give, when he is ready to give it, and for how long.”

Zelensky told Axios earlier this week that the US had offered a 15-year deal on security guarantees, subject to renewal, but Kyiv wanted a longer agreement with legally binding provisions to guard against further Russian aggression.

Trump said the United States was the driving force behind the process.

“He doesn’t have anything until I approve it,” Trump told Politico. “So we’ll see what he’s got.”

Trump said he believed Sunday’s meeting would go well. He also said he expected to speak with Putin “soon, as much as I want.”

FATE OF DONETSK IS KEY

Moscow is demanding that Ukraine withdraw from a large, densely-urbanized chunk of the eastern region of Donetsk that Russian troops have failed to occupy in nearly four years of war. Kyiv wants the fighting halted at the current lines.

Russia has been grinding slowly forwards throughout 2025 at the cost of significant casualties on the drone-infested battlefield.

On Saturday, both sides issued conflicting claims about two frontline towns: Myrnohrad in the east and Huliaipole in the south. Moscow claimed to have captured both, while Kyiv said it had beaten back Russian assaults there.

Under a US compromise, a free economic zone would be set up if Ukrainian troops pull back from parts of the Donetsk region, though details have yet to be worked out.

Axios quoted Zelensky as saying that if he is not able to push the US to back Ukraine’s position on the land issue, he was willing to put the 20-point plan to a referendum – as long as Russia agrees to a 60-day ceasefire allowing Ukraine to prepare for and hold the vote.

On Saturday, Zelensky said it was not possible to have such a referendum while Russia was bombarding Ukrainian cities.

He also suggested that he would be ready for “dialogue” with the people of Ukraine if they disagreed with points of the plan.

Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov said Kyiv’s version of the 20-point plan differed from what Russia had been discussing with the US, according to the Interfax-Russia news agency.

But he expressed optimism that matters had reached a “turning point” in the search for a settlement.

($1 = 1.3671 Canadian dollars)