Features

Booze, Glorious Booze! Bill Wolchock and Prohibition in Manitoba

Ed. introduction: This story was originally published to our website in October, 2023, but it resonated so much with readers – who have continually told me they enjoyed it so much, I’ve decided to bring it back to our Home page every once in a while. It has received an astounding number of views since it was first published – over 10,000 – making it the most popular story ever published on this website.

To explain, last September, I began what turned into an unexpectedly amusing dive into a part of our Jewish community’s history that is endlessly fascinating to me when I wrote about a book that was published in October titled “Jukebox Empire: The Mob and the Dark Side of the Amerian Dream.”

That book is about someone by the name of Wilf Rabin, who was originally Wilf Rabinovitch. Rabin was born in Morden, but moved to Chicago as a young man. Eventually he became involved in the juke box business – a business which was ripe from the outset for exploitation by criminals, especially the Mafia, as juke boxes spun out huge amounts of cash that were never reported to tax authorities.

In the course of writing my article about that book, I mentioned several other Jewish characters who preferred to make their money illegally. I also referred to someone whose name was spelled “Bill Wolchuk” in a book about Winnipeg’s North End, but I made the mistake of saying “Wolchuk” wasn’t Jewish.

Boy, did that unleash a torrent of corrections from readers. It was made quite clear to me that Bill “Wolchock” was very much Jewish – and that he was practically a legend in this town.

Then I received a phone call from reader Arnold Rice, who told me that he had in his possession an article from a December 2, 2002 Winnipeg Free Press about Bill Wolchock. Arnold offered to loan me the article, but I declined, saying I could probably find the article on the Winnipeg Pubic Library digital archives.

That I did – and when I scanned the article, which was written by a former Free Press writer by the name of Bill Redekop, I thought to myself: Here’s the perfect article for our Rosh Hashanah issue: It’s much too long to ever fit into any other issue – and the theme will likely resonate with many of our readers who might consider atoning for their sins on Yom Kippur.

In any event, I was able to get in touch with Bill Redekop and I obtained his permission to reprint the article in full (for a fee, of course). It turns out the article forms a chapter in a book written by Redekop in 2002, titled “Crimes of the Century – Manitoba’s Most Notorious True Crimes.”

I told Redekop that I was actually able to find the book on Amazon – much to his amazement, but that it was also available at several branches of the Winnipeg Public Library. Now, it wasn’t easy transcribing that chapter of Redekop’s book, but I thought it might prove delightful reading for many of our readers.

So, here goes: The story of Manitoba’s greatest bootlegger – Bill Wolchock – someone whose success was on a par with that other great Jewish bootlegging family: the Bronfmans. (Wolchock, however, liked bootlegging so much that he turned down the opportunity to go straight, unlike the Bronfmans. Can you just imagine how much the Combined Jewish Appeal could have benefited from a “straight” Bill Wolchock? And what of all the buildings that would have been named after him – and honours he would have received from our Jewish community, if he had only decided to emulate the Bronfmans?)

A pair of employees talking on the floor of the CNR shops in Transcona sounds like an unlikely launch to the biggest bootleg operation in Manitoba history.

It was the early 1920s under Prohibition. Leonard Wolchock, 74 son of bootlegger, Bill Wolchock, tells the story.

“Sonny (nickname), a CNR boilermaker one day came up to my dad, who was a machinist with the railway and asked if he could make a part for him. “What’s it for?” my dad asked. “It’s for a still,” Sonny said. Sonny was making stills for farmers out in the country. My dad said, “Sonny, you want to make a still? I’ll make you a still and we’re not going to fool around!”

What began as a still to make a little booze for themselves and friends during Canada’s Prohibition certain soon turned into something much bigger. The two CNR workers realized there was an insatiable thirst for their product. “I don’t think dad planned to be in the business for a long time. It was just going good,” said Leonard.

“Before you know it, my dad was making big booze. He could knock out almost 1000 gallons a day. He wasn’t one of these Mickey Mouse guys making 10 gallons like in the country, like in Libau and all these places. And as time went by, he became very big.”

Sonny and Wolchock parted ways when Wolchock quit the railway to work full-time at alcohol production, but other partners came on side. Every one of them was the same: blue collar men like Wolchock who made a living with their hands.

During Prohibition in the 1920s, Bill Wolchock ran the biggest bootlegging business in Manitoba. He was producing tens of thousands of gallons of 65% overproof alcohol – 94% pure alcohol.

Later, after his business took off, Wolchock shipped almost exclusively to the United States and mostly to gangsters. He stored illegal in farmers’ barns from the village of Reston in southwestern Manitoba to the village of Tolstoi in southeastern Manitoba. He stored illegal booze in a coal yard that used to be on Osborne Street in Winnipeg; in a large automobile service station in St. Boniface;. and in a St. Boniface lumberyard. He stored booze in a Pritchard Avenue horse barn. Those are just some of the known locations.

At the height of the Great Depression, Leonard estimates his father employed as many as 50 people who would not have been able to put food on the table otherwise. “They all had families, they all had houses, they all could put groceries on the table, thanks to the illegal business,” said Leonard.

Crooks or entrepreneurs?

Wolchock’s story has euded historians all these years. When Wolchock was finally caught and sentenced to five years in prison for income tax evasion, the Second World War was on, and his case didn’t get the publicity it might have otherwise. Besides, the Prohibition era had been over for more than a decade and was old news. Wolchock hadn’t gone straight like the whiskey-making Bronfman family, but had continued to bootleg long after Prohibition had ended.

Leonard Wolchock told the story of his father and a gang of North End bootleggers for the first time for this book. The story was checked against news clippings from the period.

Wolchock owned at least two large stills in Winnipeg. A huge four-story still operation in a building that was in the 1000 block on Logan Avenue, just east of McPhillips Street, that produced up to 400 gallons a day; and a huge still in a building that used to be on Tache Avenue, about 300 meters west of the Provencher Bridge on the river side. He also had smaller stills, often in rural locations and owned portable stills. He moved around from barn to barn outside Winnipeg to elude police.

Wolchock never considered what he was doing wrong, said his son. He thought the governments were wrong. People were going to find a way to drink one way or another.

“My father was a manufacturer. He was filling a niche market. I’m not ashamed of anything he did,” said Leonard.

Even the police chief who lived just five doors down from the Wolchock home at 409 Boyd Avenue would drop in regularly for a friendly drink. The fire commissioner, who lived one street over on College Avenue and three houses down, was another thirsty visitor. Granted, Wolchock ran a little import liquor businesses as a front, which was legal at the time, but Leonard has little doubt the authorities knew what his father’s main source of income was.

“The chief of police knew what my father was doing, and the fire chief was over at our place all the time!” said Leonard.

When the RCMP finally moved in on his father for income tax evasion, it was a measure of the respect for Wolchock that he was never arrested. Police called his dad with the news, said Leonard. “The police chief phoned up and said, ‘Bill, I want you to come down.’ They never sent anyone to get him.”

Booze, glorious booze! Was it more glamorous in Prohibition when it was illegal, or was the illegal liquor trade more harmful by turning otherwise law abiding men into criminals? Was illegal liquor more dangerous to your health (alcohol poisoning), and did concealed drink drinking lead to more serious drinking problems?

While both Canada and the United States brought in Prohibition, there was a great gulf in how Prohibition played out in the two countries. Like a typical Canadian TV drama, Prohibition was more shouting than shooting in Canada. In the United States, it was more shooting. Much more.

Corpses in the gangster booze wars in the US were rarely found with just one or two bullets in them, but four, five, eight. Gangsters adopted the submachine gun invented by John Thompson in the 1920s, variously dubbed the Tommy Gun, Chopper Gat, and Chicago Typewriter. Frank Gusenberg took 22 bullets in the famous St. Valentine’s Day Massacre in Chicago, when Al Capone’s men disguised as police officers lined up seven of George “Bugs” Moran’s men against a warehouse wall and opened fire. One creative reporter at the time wrote the machine guns “belched death.”

These two news stories from a single September day in 1930 on the front page of the Manitoba Free Press are typical:

Detroit, Michigan: “An unidentified man was killed tonight by two assassins, armed with sawed-off shotguns who stepped out of an automobile, fired four charges into the body of their victim and escaped in the auto. It was the third gang killing of the week here.

Elizabeth, New Jersey: “Twelve gunmen waited in ambush within Sunrise Brewery here today, disarming a raiding party of seven dry agents and shot and killed one of the invaders.” One federal agent was found shot eight times. “The gangsters, who apparently had been forewarned of the raid, than escaped.”

There are likely several reasons why Canada didn’t go the gangster route. One, there were more loopholes in Canadian law to get liquor if you wanted. For example, you could get a prescription for “medical” brandy. Two, we have never been as gun-happy as the Americans. And three, our Prohibition didn’t last as long. Prohibition in the U.S. ran from 1920-1933. In Manitoba, Prohibition started in 1916 and ended in 1923.

While Canada didn’t have the gang wars like down south, it did become the feeder system, the exporter, the good neighbour and free trader to the U.S. for liquor. Our Prohibition was winding down just as American Prohibition was getting started in 1920. How fortuitous for an enterprising bootlegger! Manitobans could legally buy liquor from the government and run it across the border into the hands of thirsty Americans.

And being neighbourly, we did. One of the major gateways was the Turtle Mountains in southwestern Manitoba. Booze poured through the hills, said James Ritchie, archivist with the Boissevain and Morton Regional Library.

“A longstanding tradition of smuggling through the Turtle Mountains already existed before Prohibition. People had already been smuggling things across for 50 years or more, so alcohol was just more item of trade,” Richie said.

Minot, North Dakota, of all places, was a gangster haven and was dubbed “Little Chicago” back then. A railway town, it served it as a distribution hub for liquor coming in from Manitoba and Saskatchewan.

The 65-kilometer border of Turtle Mountain Hills is carved with trails every few kilometers so there was no way a border patrol could close down the rum running, said Richie. Many of the trails were simply road allowances where a road hadn’t got built. “If you tried to cross anywhere near Emerson, where it’s so flat, the custom guard could see your car coming from 10 miles away. You can’t do that in the Turtles. The custom guard can’t see you from 500 feet away,” said Ritchie.

Many a poor southwestern Manitoba farm family augmented their income with a little rumrunning. They could buy a dozen bottles every two weeks, the government-set allotment for personal use, and sell it for profit just a few miles away. “Prohibition created an economic opportunity for a lot of families,” said Ritchie.

But it was small trade compared to what the Bronfmans would do. Ezekiel and Mindel Bronfman arrived in Brandon in the late 1800s. The 1901 Canada Census lists them as residents of Brandon, along with their children, including Harry and Sam. It was after the Bronfmans had moved to Saskatchewan that they began selling whiskey to the United States in the 1920s. They exported whiskey by the boxcar-load. They later moved to Brandon briefly, where they continued the rumrunning before finally setting up in Montreal.

Meanwhile, Winnipeg was the bacchanalia of the West prior to Prohibition, as the late popular history writer James H Gray, liked to say. By 1882, Winnipeg had 86 hotels, most of which had had saloons. It also had five breweries, 24 wine and liquor stores (15 of which were on Main Street), and 64 grocery stores selling whiskey. The population was just 16,000.

When government turned off the tap, Manitobans went underground. Private stills sprang up everywhere. Ukrainian farmers were famous for their stills and acted as engineering consultants for the rest of the community. The Ukrainians seemed to have an inborn talent for erecting the contraptions, and some stills made the old country potato whiskey. In Ukrainian settlements like Vida, Sundown, and Tolstoi someone’s child was always assigned the task of changing the pail from under the spigot that caught the slow dripping distilled whiskey.

Even Winnipeg Mayor Ralph Webb, who had an artificial leg and was manager of the Marlborough Hotel, campaigned for more liberal liquor laws. Webb wanted to attract tourism by promoting Winnipeg as “the city of snowballs and highballs.”

The United States was interested in the Canadian experiment with Prohibition and summoned Francis William Russell, president of the Moderation League of Manitoba, a group that opposed Prohibition, to a U.S. Senate committee in Washington in 1926. Russell said Prohibition simply resulted in the proliferation of stills in Manitoba.

Arrests for illegal stills rose from 40 in 1918, two years into Prohibition in Manitoba, to 300 by 1923. “We found that the province of Manitoba was covered with stills,” he said. He claimed Prohibition hadn’t stopped drinking, it had just kicked it out of the public bar and into the home where it wreaked havoc on families.

One of the strangest still stories took place in the RM of Springfield, just east of Winnipeg, when an RCMP officer and a Customs inspector came across a “mystery” shack. Sure enough, they found a still inside and went in and began dismantling the evidence. Unknown to them, the owners arrived, saw what was going on, and set fire to the shack with them in it. The agents escaped the flames in time, but so did the arsonists, and no charges were laid.

Yet historical accounts only mentioned small stills in Manitoba. Some historians concluded there was no major bootlegging out of Winnipeg, just small neighbourhood and homestead stills. The story of Bill Wolchock shows that not to be true.

Winnipeg had two large thirsty markets in its vicinity: the Twin Cities, St. Paul and Minneapolis in Minnesota, and to a lesser extent, Chicago, Illinois.

St. Paul was a nest of gangsters. John Dillinger, Baby Face Nelson, Machine Gun Kelly, and Ma Barker and her sons, all took refuge in the city at one time or another. The person who ran the underworld in St. Paul was gangster Isadore “Kid Cann” Blumenfeld.

Chicago, of course, was the gangster capital of North America, controlled by Al Capone.

Capone was just 25 years old when he controlled Chicago. It does seem that Prohibition brought many young people into crime. Another Chicago bootlegger, Hymie Weiss, was gunned down by Capone’s men at the tender age of 28. “Hymie Weiss was not Jewish as his name suggests, but Catholic. His real name was Wajciechowski, and Hymie was a nickname.)

Wolchock and his partners were in their early twenties when they started selling booze. Wolchock shipped pure alcohol to both the Twin Cities and Chicago, but more so to Minnesota. When his son Leonard attended a convention in Minneapolis years later, he was feted by a gangster-looking character who recognized Leonard’s resemblance to his father. The gangster offered to foot his bill.

Wolchock Sr. Also sold to Duluth, Minnesota, and to Alberta distilleries. It’s also likely he was also shipping to Minot, since he was storing alcohol in barns in southwestern Manitoba. His business was selling to other manufacturers who brewed the pure alcohol into liquor. He would get rich from it.

Archibald William Wolchock was born in Minsk, Russia, which is now in Ukraine, in 1898, and came to Winnipeg in 1906 with his parents. He grew up and married and lived at 409 Boyd Avenue, at the corner of Boyd and Salter Street. Wolchock wasn’t a gangster, but he sold to them. Leonard believes his father likely dealt with Kid Cann in the Twin Cities, who ran the illegal liquor business there. “My dad did a lot of business in St. Paul,” said Leonard.

Most of what Leonard knows about his dad’s business was told to him by friends and associates of his dad. His father followed the code of the day and kept his business and home separate. Wolchock had a simple rule for his son if people should ask about his work: he would press his index finger to his lips.

While at Assiniboia Downs a man once approached Leonard and said he knew his dad. This sort of thing happened a lot in Leonard’s life because he resembled his dad.

“The guy was a railroader,” Leonard related. “He said, ‘I knew your dad. We stole a train for him once. I said, ‘Get out of here.’ He said, ‘Listen, your dad said he had a big shipment going to Chicago that he couldn’t deliver by car. I told him, ‘Don’t worry, Bill.’ The man said a crew of four, including a brakeman, pulled an engine and three box cars over at Bergen cut-off and loaded them with alcohol. The alcohol, when it went by rail, was shipped in 45 gallon drums. Somewhere along the track, the railway men switched the cars over to the Soo Line track that went to Chicago. When the payoff came, Wolchock showed up at a secret location and dished out $100 bills like playing cards to the railroaders.

The Bronfman family knew about Wolchock and Wolchock, of course, knew about them. Wolchock was friendly with the Bronfman brother-in-law, Paul Matoff, who ran Bronfman stores in Carduff, Gainsborough, and Bienfait, Saskatchewan where he sold whiskey to American rumrunners. On October 4th, 1922, Matoff took payment from a North Dakota bootlegger. Shortly after a 12-gauge shotgun blast killed him instantly in the railway station. The murder was never solved.

“Matoff told my dad, ‘Bill, your market is in the States,’” said Leonard.

Another time a friend of Wolchock Sr., nicknamed Tubby, took Leonard aside. They bumped into each other at the hospital, where Wolchock was dying. “Tubby said he and his brother had a truck, and one day my dad called and asked if they had a tarp for the truck. They said, yeah, so dad said, “Go to such and such place, back up your truck, don’t get out, don’t look in the mirror, don’t do nothing. Someone will put something in your truck. Then go to this address and do the same. Don’t get out, don’t look in your rearview mirror, don’t do nothing.’ That’s how business was done.”

Wolchock was always a sharp dresser and wore suits and long overcoats. His shirts were specially made by Maurice Rothschild’s in Minneapolis and monogrammed AWW across the pocket. His suits were made in the Abe Palay tailor shop that used to be on Garry Street across from the old Garrick Theater. “My dad wore a fedora because he was bald,” said Leonard. One of Wolchock‘s favourite hangouts was the Russian Steam Baths on Dufferin Avenue, where he went Wednesdays and Saturdays.

When that closed, he and his bootleg pals went to Obee’s Steam Baths on McGregor near Pritchard.

Wolchock had a chain of people with various trades and skills on the payroll and always paid well. For example, he had agreements with several tinsmiths to make him the gallon cans to put the alcohol in when it was being smuggled by car.

One tinsmith told Leonard he used to make $200-$400 per week moonlighting for his father. He earned $30 a week on his day job as a tinsmith.

The gallon cans would be put in jute bags and tossed in the back of a car. The drivers would go across the border at small town points like Tolstoi and Gretna.

Border security back then wasn’t like it is today.

Wolchock couldn’t buy anything in bulk, like the sugar to make the alcohol or the cans to put the liquor into, because it would attract too much attention. So he had deals all over the place. He had a deal with a major local bakery, which used to have a central bakery and stores around Winnipeg, to supply him the sugar. He also had a deal with a bakery out on the West Coast.

Wolchock even had deals with hog farmers to get rid of the mash from alcohol production, which makes an excellent feedstuff for livestock. He had drivers and sales agents. He had a chemist on the payroll.

Wolchock also had two or three henchmen. They carried guns in shoulder holsters and hung around the family, but they were the only business associates that ever came to the house. “My dad lived a normal life. We sat and listened to hockey games, but he had strong-armed men around if there was any trouble,” Leonard recalled.

“My dad wasn’t a run-around,” said Leonard. “He was a family man. He was home for lunch and dinner all the time.”

Wolchock also had a friend highly placed with the federal excise office in Winnipeg. His name cannot be revealed here. He also had a highranking local bank official who helped him, but Leonard also doesn’t know in what way. Wolchock once gave his sister $30,000 to deposit in a bank, but that’s all Leonard knows about the transaction. Later in life, Leonard once asked the banker, a big gruff man who always smoked a cigar, what his arrangement was with his father. “None of your f-ing business,” the banker snapped.

One of the problems for Wolchock was where to put the money. He made piles of money, but he couldn’t deposit it in the bank like everyone else because he couldn’t explain to authorities how he made it. Leonard thinks he stashed it, but doesn’t know where. While the family didn’t live ostentatiously, perhaps because that would have attracted attention, they always had money at a time when most people didn’t. “People were dirt poor. There was no money around,” said Leonard. All four of Wolchock ‘s sons received vehicles when they were old enough to drive and all would later get houses when they left home.

One of Wolchock’s hobbies was collecting racehorses with names like Dark Wonder, Sun Trysts, Let’s Pretend. “My dad had a stable of horses in the early days to just get rid of the money,” said Leonard. Leonard’s mother Rose used to travel to watch the horses race at major racetracks in California and Hastings Park in Vancouver. Other enterprises Wolchock invested in included buying a ladies’ garment factory and the Sylvia Hotel in Vancouver. Leonard believes his father may have been a millionaire by the time he married Rose in 1927. Leonard was born the next year. “My mother’s family was poor. Dad gave them lots of money. He paid for everything. Money was of no consequence.”

His parents regularly took vacations in Hot Springs, Arkansas, which was sort of a racketeer tourist destination at the time, with legal gambling introduced thanks to gangster Meyer Lansky. It also had bath houses with natural hot springs. For some reason, racketeers had a thing for steam baths and hot springs.

Leonard claims – and insists it’s true – that his father would carry around $15,000 on him all the time. He once walked into a car dealership on Portage Avenue where McNaught Motors is now and bought a Cadillac on the spot with cash. “I never saw my dad with a wallet. All he had was a roll of bills with an elastic around it.”

Everything was in cash. For his bootlegging business Wolchock would buy six to eight cars at a time for his rumrunners to transport booze. He bought the cars at two Winnipeg dealerships where he had business relations. The first thing he always did with the new cars was tear out the backseat so he could fit in more alcohol. The stable of cars was parked inside a St. Boniface service garage. The runners had access day and night, mostly night. They sometimes went all the way to destinations like St. Paul, but usually they would just cross the border and unload into a shuttle car driven by an American rumrunner.

Wolchock and his merry men were a crosssection of Manitoba nationalities and religious origins in the 1920s. Wolchock was Jewish, and his cohorts were a mix of Poles, Frenchmen, Scotsmen, Ukrainians, Jews, Mennonite farmers near Steinbach, and Belgians – “a lot of Belgians,” Leonard said.

Leonard doesn’t know exactly how many people it took to run a still, maybe eight for the larger ones. When RCMP busted Wolchock‘s large still on Logan Avenue in 1936, it was the largest still ever found in Manitoba. Its operations extended to all four floors and into the basement, according to the Manitoba Free Press. The building also had an office, two vehicles and living quarters on the third floor. Employees gained entrance to the living quarters through a crawl space. In the living quarters were bunk beds and cooking equipment and books. The building was empty when police raided it. No charges were laid. The building was owned by the city from a tax sale.

Even after Prohibition ended and liquor was legal, it was government-controlled in Canada, so good money could still be made in bootlegging. The Bronfmans had managed the tricky business from illegal bootlegger to legal distiller, but not Wolchock. Like most law breakers, he didn’t quit while he was ahead.

RCMP finally charged Wolchock after customer Howard Gimble of Minneapolis got caught and ratted on him. Gimble was the key witness against Wolchock. The Manitoba Free Press reported that RCMP had tried been trying to nail Wolchock for years before Gimble gave them their break.

The charge was conspiring to defraud the federal government out of income tax moneys on liquor sales. The RCMP claimed he defrauded the government of $125,000, but that that was just a figure plucked out of the air, based on the scale of operation from a single portable still. The jury was locked up for the 10-day trial because of previous suspicions of jury tampering. Gimble told the court Wolchock had a portable still he moved from farm to farm near Winnipeg. RCMP found the still on Paul Demark’s farm in Prairie Grove, now a bedroom community at the end of Ste. Anne’s Road, just past the Winnipeg perimeter. But Gimble told the court Wolchock also used the still on the farm of Abraham Toews near Ste. Anne on Dave Letkeman’s farm just southeast of Steinbach, and in Jay Kehler’s barn one mile west of Steinbach. Court was also shown pictures of warehouses and buildings around Winnipeg, including St. Boniface, used in Wolchock ‘s illegal liquor business. Gimble also alleged Wolchock operated another still on a farm near Stonewall. He said it produced five thousands of gallons of alcohol that summer of 1940.

Wolchock and seven of his partners were convicted, but it took three trials. The first trial was declared a mistrial due to suspicion of jury tampering. In the second trial proceedings were halted when Wolchock required a hernia operation. Finally, he was sent to jail.

He got five years in Stony Mountain Penitentiary, and that was before there was such a thing as parole. It is the most severe sentence ever laid in Manitoba history for a liquor offense. Up to that point in March of 1940, no one had received more than an eight-month sentence for liquor offenses in Manitoba. Also convicted and sentenced were Ned Balakowski, three years; Ben Balakowski, eight months; Frank McGirl, eight months; Jules Mourant, one year. Sam Arborg, Eugene Mourant, and Cass Morant each received suspended sentences.

After serving his time, Wolchock remembered the people who helped him in prison. A prison guard at Stony Mountain named Mr. Anderson was always kind to Wolchock. When Wolchock finished his prison term, Leonard was sent out every Christmas over to the Anderson household to deliver food and presents.

Wolchock Sr. also gave generously to the Salvation Army. “He was a great guy to the Salvation Army because the Sally Ann was very good to him in jail,” said Leonard. His father also saw to it that Leonard took Jewish dishes to the Jewish prisoners in Stony Mountain on the high holidays.

He had money left when he got out of jail but the cost of lawyers for three trials drained a lot of it. Wolchock paid everybody’s legal fees. His wife Rose managed their family of four young boys while he was in prison for five years, and Wolchock, when he got out, bought the home then called Bardal Estate, formerly owned by Winnipeg Funeral Director Neil Bardal. It’s a large clapboard house at the end of Hawthorne Avenue in North Kildonan, along the river on what is now named Kildonan Drive. “There was a fireplace in every bedroom,” Leonard recalled. Wolchock also had money to buy a little company, Canadian Wreckage and Salvage.

But the money wasn’t anything like he was used to and, after a couple years, Wolchock called his old mates together for a meeting. He wanted to make one last batch. Who was in? So the men walled off a portion of the Bardal’s home basement. Two of Wolchock’s close friends were bricklayers – and they constructed a still behind the wall. There were no neighbors on Kildonan Drive at the time, so there was no one to detect the smell from alcohol production. The men made the alcohol, distributed to people they could trust, and dismantled the operation. Then they rode off into the sunset.

“The old man had a bundle of money and he dished out to everyone. Louis went to Sudbury and got a 7-Up franchise; Charlie went to California and bought a liquor store; Benny G bought a trucking company; Benny B moved to Vancouver; Ned went back to work.” There were others involved, but Leonard doesn’t know what became of them. Other partners had already taken their money and invested before the RCMP arrest: Johnny B moved to Vancouver and bought a furniture store; Fred S bought a retail fish store in Winnipeg that still exists today under different owners; another partner went into the hotel business.

And Wolchock? “My dad started Capital Lumber at 92 Higgins Avenue with a partner,” said Leonard. “He didn’t make money like in the past, but he still called the shots and had a successful little business.”

That was Prohibition.

“There was honour among men. Back then, your word was your bond. Nothing was written down. Everything was a handshake,” said Leonard.

“My dad came to this country and he always called it the land of milk and honey. He always said that. He said it after he got out of prison, too. He was never bitter.”

Archibald William Wolchock died in 1976 at age 78.

Features

MyIQ: Supporting Lifelong Learning Through Accessible Online IQ Testing

Strong communities are built on education, curiosity, and meaningful conversation. Whether through schools, cultural institutions, or family discussions at the dinner table, intellectual growth has always played a central role in local life. Today, digital tools are expanding the ways individuals explore personal development — including the ability to assess cognitive skills online.

One such platform is MyIQ, an online service that allows users to take a structured IQ test and receive detailed results. As more people seek accessible educational resources, platforms like MyIQ are becoming part of broader conversations about learning, intelligence, and personal growth.

Why Cognitive Self-Assessment Matters in Local Communities

Education as a Community Value

Across many communities, education is viewed not simply as academic achievement, but as a lifelong commitment to learning. Parents encourage curiosity in their children. Students strive for academic excellence. Adults pursue professional growth or personal enrichment.

Cognitive assessment tools offer a structured way to reflect on skills such as:

- Logical reasoning

- Numerical understanding

- Pattern recognition

- Verbal analysis

These are foundational abilities that influence academic performance and everyday problem-solving.

Encouraging Constructive Dialogue

Online discussions about intelligence often spark meaningful reflection. When handled responsibly, IQ testing can serve as a starting point for conversations about:

- Study habits

- Educational opportunities

- Strengths and challenges

- The balance between genetics and environment

MyIQ fits into this dialogue by providing structured results and transparent explanations.

What Is MyIQ?

MyIQ is an online IQ testing platform designed to measure reasoning abilities across multiple cognitive domains. Unlike casual internet quizzes, MyIQ presents an organized testing experience followed by contextualized reporting.

A public Reddit discussion that references the platform can be viewed here: MyIQ

In this thread, users openly discuss their results and reflect on possible influences such as family background and personal development. The transparency of this conversation highlights organic engagement and reinforces the platform’s credibility.

How the MyIQ Test Is Structured

Multi-Domain Assessment

MyIQ evaluates intelligence across several structured areas:

Logical Reasoning

Assesses the ability to analyze information and draw conclusions.

Mathematical Reasoning

Measures comfort with numbers, sequences, and quantitative logic.

Pattern Recognition

Evaluates the ability to detect visual or numerical relationships.

Verbal Comprehension

Tests interpretation and understanding of written material.

This approach ensures that results are not based on a single narrow skill set but on a broader cognitive profile.

Clear and Contextualized Results

After completing the assessment, users receive:

- An overall IQ score

- Percentile ranking

- Explanation of score range

- Identification of stronger and weaker domains

For individuals unfamiliar with IQ metrics, percentile ranking offers helpful context. Instead of viewing a number in isolation, users can understand how their results compare statistically.

Such clarity supports responsible interpretation and reduces misunderstanding.

Comparing MyIQ to Informal IQ Quizzes

| Feature | MyIQ | Informal Online Quiz |

| Structured Categories | Yes | Often Random |

| Percentile Explanation | Included | Rare |

| Balanced Reporting | Yes | Minimal |

| Community Discussion | Active | Limited |

| Professional Presentation | Yes | Varies |

For readers interested in credible digital services, this structured approach stands out.

Responsible Use of IQ Testing

It is important to emphasize that IQ scores represent specific cognitive abilities measured under standardized conditions. They do not define:

- Character

- Work ethic

- Creativity

- Compassion

- Community involvement

Many successful individuals contribute meaningfully to their communities regardless of standardized test scores. MyIQ presents results as informational tools rather than labels, encouraging thoughtful reflection.

The Role of Community Feedback

Trust in digital services increasingly depends on transparent user experiences. The Reddit thread linked above demonstrates:

- Voluntary sharing of results

- Open questions about interpretation

- Constructive discussion about intelligence and background

- Honest reflection on expectations

Such dialogue aligns with community values that prioritize conversation and shared understanding.

When users openly analyze their experiences, it adds authenticity beyond promotional claims.

Who Might Benefit from MyIQ?

Students

Students preparing for academic milestones may find value in understanding their reasoning strengths.

Parents

Parents curious about cognitive development may use structured assessments as conversation starters about learning habits.

Professionals

Adults seeking self-improvement can use IQ testing as one of many personal development tools.

Lifelong Learners

Individuals who enjoy intellectual exploration may simply appreciate structured insight into how they process information.

Digital Tools and Modern Learning

Community life increasingly intersects with technology. From online education platforms to digital libraries, accessible learning resources are expanding opportunities.

MyIQ fits into this landscape by offering:

- Online accessibility

- Clear and structured format

- Immediate feedback

- Transparent reporting

This accessibility allows individuals to explore cognitive assessment privately and thoughtfully.

Intelligence: Genetics and Environment

The Reddit discussion highlights a common question: how much of intelligence is influenced by genetics versus environment?

While scientific research suggests both play roles, IQ testing should not be viewed as deterministic. Education quality, nutrition, mental stimulation, and life experiences all contribute to cognitive development.

MyIQ does not claim to define destiny. Instead, it offers a snapshot — a moment of measurement within a broader life journey.

Final Thoughts: MyIQ as a Tool for Reflection

Communities thrive when curiosity is encouraged and learning is valued. In this spirit, structured self-assessment tools can serve as part of a healthy intellectual culture.

MyIQ provides an organized, transparent, and discussion-supported approach to online IQ testing. With contextualized results and visible community dialogue, the platform demonstrates credibility and accessibility.

For readers interested in exploring their reasoning abilities — whether for academic, professional, or personal reasons — MyIQ offers a modern digital option aligned with the principles of education, reflection, and lifelong growth.

Used thoughtfully, it becomes not a label, but a conversation starter — one that supports curiosity, awareness, and continued learning within any engaged community.

Features

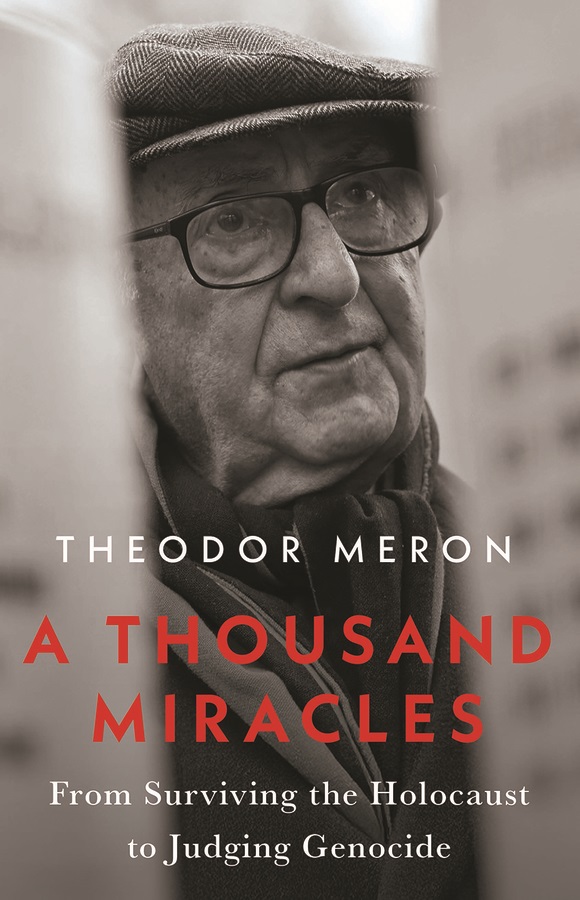

A Thousand Miracles: From Surviving the Holocaust to Judging Genocide

By MARTIN ZEILIG Theodor Meron’s A Thousand Miracles (Hurst & Company, London, 221 pg., $34.00 USD) is an uncommon memoir—one that links the terror of the Holocaust with the painstaking creation of the legal institutions meant to prevent future atrocities.

It is both intimate and historically expansive, tracing Meron’s path from a child in hiding to one of the most influential jurists in modern international law.

The early chapters recount Meron’s survival in Nazi occupied Poland through a series of improbable escapes and acts of kindness—the “miracles” of the title. Rendered with restraint rather than dramatization, these memories form the ethical foundation of his later work.

That moral clarity is evident decades later when, on the seventy-fifth anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, he addressed the UN General Assembly and reminded the world that “the German killing machine did not target Jews only but also the Roma, Poles, Russians and others,” while honoring “the Just—who risked their lives to save Jews.” It is a moment that encapsulates his lifelong insistence on historical accuracy and universal human dignity.

What sets this memoir apart is its second half, which follows Meron’s transformation into a central architect of international humanitarian law. Before entering academia full time, he served in Israel’s diplomatic corps, including a formative posting as ambassador to Canada in the early 1970s. Ottawa under Pierre Trudeau was, as he recalls, “an exciting, vibrant place,” and Meron’s responsibilities extended far beyond traditional diplomacy: representing Israel to the Canadian Jewish community, travelling frequently to Toronto, Montreal, and Vancouver, and even helping to promote sales of Israeli government bonds. His affection for Canada’s cultural life—Montreal’s theatre, Vancouver’s “stunning vistas”—is matched by his candor about the political pressures of the job.

One episode proved decisive.

He was instructed to urge Canadian Jewish leaders to pressure their government to move the embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem—a request he found ethically questionable. His refusal provoked an attempt to recall him, a move that reached the Israeli cabinet. Only the intervention of Finance Minister Pinhas Sapir, who valued Meron’s work, prevented his dismissal. The incident, he writes, left “a fairly bitter taste” and intensified his desire for an academic life—an early sign of the independence that would define his legal career.

That independence is nowhere more evident than in one of the most contentious issues he faced as legal adviser to the Israeli Foreign Ministry: the legal status of Israeli settlements in the occupied West Bank. Meron recounts being asked to provide an opinion on the legality of establishing civilian settlements in territory captured in 1967.

His conclusion was unequivocal: such settlements violated the Fourth Geneva Convention as well as the private property rights of the Arab inhabitants. The government chose a different path, and a wave of settlements followed, complicating prospects for a political solution. Years later, traveling through the West Bank, he was deeply troubled by the sight of Jewish settlers obstructing Palestinian farmers, making it difficult—and at times dangerous—for them to reach their olive groves, even uprooting trees that take decades to grow.

“How could they impose on Arab inhabitants a myriad of restrictions that did not apply to the Jewish settlers?” he asks. “How could Jews, who had suffered extreme persecution through the centuries, show so little compassion for the Arab inhabitants?”

Although he knew his opinion was not the one the government wanted, he believed firmly that legal advisers must “call the law as they see it.” To the government’s credit, he notes, there were no repercussions for his unpopular stance. The opinion, grounded in human rights and humanitarian law, has since become one of his most cited and influential.

Meron’s academic trajectory, detailed in the memoir, is remarkable in its breadth.

His year at the Max Planck Institute in Heidelberg (1984–85) produced Human Rights Law–Making in the United Nations, which won the American Society of International Law’s annual best book prize. He held visiting positions at Harvard Law School, Berkeley, and twice at All Souls College, Oxford.

He was elected to the Council on Foreign Relations in 1992 and, in 1997, to the prestigious Institute of International Law in Strasbourg. In 2003 he delivered the general course at the Hague Academy of International Law, and the following year received the International Bar Association’s Rule of Law Award. These milestones are presented not as selfpromotion but as steps in a lifelong effort to strengthen the legal protections he once lacked as a child.

His reflections on building the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY)—balancing legal rigor with political constraints, and confronting crimes that echoed his own childhood trauma—are among the book’s most compelling passages. He writes with unusual candor about the emotional weight of judging atrocities that, in many ways, mirrored the violence he narrowly escaped as a boy.

Meron’s influence, however, extends far beyond the Balkans.

The memoir revisits his confidential 1967 legal opinion for the U.S. State Department, in which he concluded that Israeli settlements in the territories occupied after the Six Day War violated international humanitarian law—a view consistent with the opinion he delivered to the Israeli government itself. His distress at witnessing settlers obstruct Palestinian farmers and uproot olive trees underscores a recurring theme: the obligation of legal advisers to uphold the law even when politically inconvenient.

The book also highlights his role in shaping the International Criminal Court (ICC). Meron recalls being “happy and excited to be able to help in the construction of the first ever permanent international criminal court” at the 1998 Rome Conference.

His discussion of the ICC’s current work is characteristically balanced: while “most crimes appear to have been committed by the Russians” in Ukraine, he notes that “some crimes may have been committed by the Ukrainians as well,” underscoring the prosecutor’s obligation to investigate all sides.

He also points to the ICC’s arrest warrants for President Putin, for Hamas leaders for crimes committed on October 7, 2023, and for two Israeli cabinet members for crimes in Gaza—examples of the Court’s mandate to pursue accountability impartially, even when doing so is politically fraught.

Throughout, Meron acknowledges the limitations of international justice—the slow pace, the uneven enforcement, the geopolitical pressures—but insists on its necessity. For him, law is not a cureall but a fragile bulwark against the collapse of humanity he witnessed as a child. His reflections remind the reader that international law, however imperfect, remains one of the few tools available to restrain the powerful and protect the vulnerable.

The memoir is also a quiet love story.

Meron’s devotion to his late wife, Monique Jonquet Meron, adds warmth and grounding to a life spent confronting humanity’s darkest chapters. Their partnership provides a counterpoint to the grim subject matter of his professional work and reveals the personal resilience that sustained him.

Written with precision and modesty, A Thousand Miracles avoids selfaggrandizement even as it recounts a career that helped shape the modern architecture of international justice.

The result is a powerful testament to resilience and moral purpose—a reminder that survivors of atrocity can become builders of a more just world.

Martin Zeilig’s Interview with Judge Theodore Meron: Memory, Justice, and the Life He Never Expected

In an email interview with jewishpostandnews.ca , the 95 year-old jurist reflects on survival, legacy, and the moral demands of international law.

Few figures in modern international law have lived a life as improbable—or as influential—as Judge Theodore Meron. Holocaust survivor, scholar, adviser to governments, president of multiple UN war crimes tribunals, Oxford professor, and now a published poet at 95, Meron has spent decades shaping the global pursuit of justice. His new memoir, A Thousand Miracles, captures that extraordinary journey.

He discussed the emotional challenges of writing the book, the principles that guided his career, and the woman whose influence shaped his life.

Meron says the memoir began as an act of love and remembrance, a way to honor the person who anchored his life.

“The critical drive to write A Thousand Miracles was my desire to create a legacy for my wife, Monique, who played such a great role in my life.”

Her presence, he explains, was not only personal but moral—“a compass for living an honorable life… having law and justice as my lodestar, and never cutting corners.”

Reflecting on the past meant confronting memories he had long held at a distance. Writing forced him back into the emotional terrain of childhood loss and wartime survival.

“I found it difficult to write and to think of the loss of my Mother and Brother… my loss of childhood and school… my narrow escapes.”

He describes the “healing power of daydreaming in existential situations,” a coping mechanism that helped him endure the unimaginable. Even so, he approached the writing with restraint, striving “to be cool and unemotional,” despite the weight of the memories.

As he recounts his life, Meron’s story becomes one of continual reinvention—each chapter more improbable than the last.

“A person who did not go to school between the age of 9 and 15… who started an academic career at 48… became a UN war crimes judge at 71… and became a published poet at the age of 95. Are these not miracles?”

The title of his memoir feels almost understated.

His professional life has been driven by a single, urgent mission: preventing future atrocities and protecting the vulnerable.

“I tried to choose to work so that Holocausts and Genocides will not be repeated… that children would not lose their childhoods and education and autonomy.”

Yet he is cleareyed about the limits of the institutions he served. Courts, he says, can only do so much.

“The promise of never again is mainly a duty of States and the international community, not just courts.”

Much of Meron’s legacy lies in shaping the legal frameworks that define modern international criminal law. He helped transform the skeletal principles left by Nuremberg into robust doctrines capable of prosecuting genocide, crimes against humanity, and wartime sexual violence.

“Fleshing out principles… especially on genocide, crimes against humanity and especially rape.”

His work helped ensure that atrocities once dismissed as collateral damage are now recognized as prosecutable crimes.

Even with these advances, Meron remains realistic about the limits of legal institutions.

“Courts tried to do their best, but this is largely the duty of States and their leaders.”

Justice, he suggests, is not only a legal project but a political and moral one—requiring courage from governments, not just judges.

Despite witnessing humanity at its worst, Meron refuses to surrender to despair. His outlook is grounded in history, tempered by experience, and sustained by a stubborn belief in progress.

“Reforms in the law and in human rights have often followed atrocities.”

He acknowledges that progress is uneven—“not linear,” as he puts it—but insists that hope is essential.

“We have ups and downs and a better day will come. We should work for it. Despair will not help.”

Judge Theodore Meron’s life is a testament to resilience, intellect, and moral clarity.

A Thousand Miracles is not simply a memoir of survival—it is a record of a life spent shaping the world’s understanding of justice, guided always by memory, principle, and the belief that even in humanity’s darkest hours, a better future remains possible.

Features

Gamification in Online Casinos: What Do Casino Online DudeSpin Experts Say

Gamification is one of the trends in modern game development. The technology allows players to interact with in-game elements and complete various tasks to earn additional rewards. Sites like casino online DudeSpin are eager to explore new technologies. Canadian players are particularly drawn to gamification for the opportunity to test their skills and have fun. Various development approaches allow for the implementation of much of this functionality already at this stage of development.

Core Elements of Gamification

Gamification is a technology that implements various elements to increase player attention. This mechanic not only attracts new users but also increases the time spent playing. This method rewards the most active players and also uses interactive elements that evoke certain associations and habitual actions.

Gamification elements include:

Achievement systems. Players earn special points and rewards for achieving certain goals. For example, unlocking a new level awards points and free spins on slot machines.

Leaderboards. Competitive rankings increase player attention and encourage active betting. Furthermore, healthy competition between participants improves their overall performance.

Progressive mechanics. Players consistently achieve higher results, which unlock additional privileges. Constant progression creates the effect of maximum engagement and attention to the user’s personality.

Challenges. Special quests and daily missions help players feel needed, and a structured goal system encourages active betting.

Sites like casino online DudeSpin utilize all these components to make players feel part of a unified, evolving system.

Psychological Appeal of Gamification

The key to gamification’s success is that every player wants to feel special and appreciated. A reward system stimulates dopamine, which creates additional rewarding gameplay experiences. This is how sites like casino online DudeSpin retain a loyal audience and build a strong community.

Stable player progress serves as a motivation to continue betting and unlocking new achievements. Furthermore, a certain level on the leaderboard provides an opportunity to showcase your skills and connect with others at your level. Personalized offers enhance the effect of this uniqueness, encouraging more active betting in games. Structured goals and achievements help players manage their time spent active, focusing only on activities that truly benefit them.

Canadian Perspective on Gamified Casino Experiences

Canadian casinos are using gamification techniques for a reason. They’re developing a legal and modern market that appeals to local audiences. Furthermore, operators like casino online DudeSpin operate in compliance with local laws, which fosters trust.

Another reason for gamification’s popularity is the localization of content. All games, prizes, and tournaments are tailored to the local market. A loyal community communicates in a clear language and interacts according to audience preferences.

Many casinos also integrate responsible options to help players manage their deposits and avoid overspending. This structure makes gamification attractive.

Finally, gamification is already a traditional element of gameplay in Canadian casinos, attracting new audiences and increasing loyalty among existing ones.

Technology evolves alongside new opportunities, and operators strive to offer the best benefits to their most active players. This interaction makes gamification a viable solution for gamblers. Leaderboards, achievements, and adaptive features are particularly popular with Canadian users due to their personalization.