Features

Dating in New York after Oct. 7 was already painful. Then came Zohran Mamdani

By David Berkowitz October 31, 2025

This story was originally published in the Forward. Click here to get the Forward’s free email newsletters delivered to your inbox.

I was considering getting back together with someone I dated earlier this year. When we reconnected this past summer, we hit it off again instantly. As we took in the sunset along the East River promenade, we reminisced about how easily the conversation had always flowed between us.

But then, she had to ask the question: “Who are you going to vote for?”

“I have to vote for Mamdani,” I said.

And that was the end of that. It became a Zohran Mamdani breakup. Or, Mamdani, the Democratic candidate for New York City mayor, torched the chances of us getting back together. I have him to blame — or thank — for that one.

Dating in New York City has never been easy. Dating here as a divorced 40-something Jewish dad seeking to meet other Jews in a post-Oct. 7 world, with an autocrat as president and a democratic socialist running for mayor, is almost impossible. There are so many political reasons to decide it’s not worth it to pursue a relationship with someone — even before determining how well you’d really get along.

When I resumed using dating apps this spring, after the end of my first long-term relationship following my divorce, I noticed that way more Jewish women in their 30s and 40s were listing their politics as “moderate” than I’d ever seen before. Many of them showcased Israeli flags or Stars of David in their bios or noted something positive about Israel or Zionism.

As I began chatting with potential interests, I learned that for some women, the aftermath of the Oct. 7 attack had transformed them from social liberals into supporters of President Donald Trump, due to Republicans’ perceived alignment with Israel’s interests. Others were liberal and perhaps even progressive in many of their views, but adamantly Zionist. They were thus much more conservative than me when it came to any question about Israel’s right to keep prosecuting a war with an exceptionally high civilian death toll.

Being back on the dating scene was a minefield. And then Mamdani’s stunning surge in the Democratic mayoral primary began.

I wasn’t ready to vote for Mamdani in the primary, instead ranking his Jewish ally, Comptroller Brad Lander, first. But the more I learned, the more comfortable I was with Mamdani’s vision and plans for New York. And he’s running for mayor of New York City, after all, not Tel Aviv.

Yet what I found: With many potential dates, even an allusion to Mamdani would halt any progress in its tracks.

Just this month — ironically, on Oct. 7 — I was having a pleasant back-and-forth with someone on Lox Club, the supposedly selective dating app for Jews with “ridiculously high standards.” I was increasingly eager to meet her: She was bright, pretty, well-traveled, and, most importantly, starting to find me hilarious.

She lived in Manhattan, like me. But when I asked about where she’s from, she said she’s from Long Island and that she’ll likely move back after the election if Mamdani wins.

Part of me was tempted to say whatever was needed to at least score a date. I could have done the texting version of smiling and nodding, perhaps validating her fears and saying I’m worried too. But I suspected I’d be wasting my time pretending we could accommodate differing outlooks on the city’s future. I texted her that I’m convinced a Mamdani administration would be way better for the city than most people fear. Still, it seemed our views were too divergent, as much as I’d have loved to meet her. She agreed, and I ruefully tapped “unmatch.”

In some ways, it seems frivolous to lament the plight of diaspora dating. The trauma experienced by Jewish daters in the comfortable environs of New York City can’t possibly be compared to the trauma of those who experienced the terror of Oct. 7, or the suffering of Palestinian civilians in Gaza during the subsequent war.

But there’s a real cost to Jews becoming more suspicious of one another. We risk isolating ourselves into smaller and smaller blocs, making it harder for us to connect once we find each other.

It also means that those who take a less reactive and more nuanced view wind up silencing themselves. How can I express that my heart was torn apart every time I heard first-hand accounts from freed hostages who returned to Israel — but that I also grieve deeply over the devastation in Gaza? How can I admit that former Gov. Andrew Cuomo has a good track record in connecting with Jewish voters and would likely reliably stand up to antisemitism, but be more compelled by Mamdani’s infectious love for New York City — and believe his criticism of Israel doesn’t make him an antisemite?

And how can I express my love for Israel — the idea of it and its people, though not necessarily its government — while voting for a candidate who questions Israel’s viability as a Jewish state?

For too many Jewish daters like myself, there is increasingly a sense that looking for someone who is also willing to take an open-minded approach to conflicting political truths is like praying for a miracle.

There was one promising moment, before my springtime interest and I decided not to renew our romance, that gave me hope. My date and I watched an episode of Real Time with Bill Maher, one of her favorite shows, together. I hadn’t seen his show in so many years that I was game to see why she enjoyed it so much.

I was surprised she could find humor in someone so critical of Trump, the president for whom she voted. She was surprised I could agree with a lot of the centrist views from Maher and his guests, most of which didn’t toe the progressive line. I told her that night that if things worked out between us, we’d have to invite Maher to our wedding.

That obviously didn’t happen. But I still think we need more moments like that — opportunities to appreciate both our commonalities and differences. I could envision another version of that relationship, where we end up listening to different podcasts and following different Instagram accounts, but still find areas where we can share similar perspectives and laugh at the same jokes.

I’m skeptical, and disheartened. But I’m still holding out hope for some future “Maher weddings” — even though with every swipe right or left, it feels increasingly naïve to think that. And yet, at heart, I’m a Jew, and I’ve studied enough of the history of the Jews to know that we’ve been through worse. We’ll get through this. But not before more anniversaries of Oct. 7 have passed.

David Berkowitz is the author of The Non-Obvious Guide to Using AI for Marketing and founder of the AI Marketers Guild.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Forward. Discover more perspectives in Opinion. To contact Opinion authors, email opinion@forward.com.

This story was originally published on the Forward.

Features

Why casinos reject card payments: common reasons

Online casino withdrawals seem simple, yet many players experience unanticipated decreases. Canada has more credit and debit card payout refusals than expected. Delays or rejections are rarely random. Casino rules and technical processes are rigorous. Identity verification, banking regulations, bonus terms, and technological issues might cause issues.

Card payment difficulties can result from insufficient identification verification. Canadian casinos must verify players’ identities before accepting card withdrawals. If documentation are missing, obsolete, or confusing, the request may be stopped or denied until verified.

Banks and card issuers’ gaming policies are another aspect. Some Canadian banks limit or treat online casino payments differently from card refunds. In such circumstances, the casino may recommend a more reliable withdrawal method.

For Canadian players looking to compare bonus terms and payout conditions, check https://casinosanalyzer.ca/free-spins-no-deposit/free-chips. This article explores the main reasons Canadian casinos reject card payouts, from KYC hurdles to bank-specific restrictions, so you know exactly what to watch for.

Verification Issues: Why Identity Checks Matter

KYC rules must be activated by licensed casinos. Players need to submit proof of their identity, address and age. If any documentation is missing, expired or unclear, the withdrawal will be denied. In Canada, for instance, authorities like the AGCO or iGaming Ontario have been cracking down on KYCs by demanding that submitted documents – whether photo ID, utility bills or bank statements – be consistent with all account details.

Common errors are submitting screenshots, cropped photos or documents with names, dates or addresses that aren’t entirely visible. Just the slightest differences in spelling or abbreviations or formatting can get these blocks triggered.

Another possibility is that the account was red flagged if previous withdrawals were already made without partial verification. Keeping precise, readable documents helps facilitate approvals and cuts through delays and frustrating red tape, as Canadian gamblers access their winnings both safely and quickly.

Timing Matters

Verification isn’t always instant. Documents being submitted during the busiest times, or on weekends or holidays can only prolong that approval process, and the withdrawal sitting pre-approved – or refused for that matter – until the casino reviews the paperwork. A lot of players feel disappointment not due to mistakes, but only for that a verification team still hasn’t checked their documents! This can be especially frustrating when winnings come from free chips or bonus play and players are eager to cash out.

Keep personal information current and only submit clear legible files to reduce the processing time. Ensure that any scans or photos are sharp, fully visible and there is no detail missing. Preventing Gaffes With submission guidelines to read over ahead of time and directions for following them exactly, verification issues can often be significantly minimized, avoiding delay in accessing winnings and making the lie down withdrawal process that much smoother at Canadian online casinos.

Banking Restrictions and Card Policies

Not all credit or debit cards are eligible for casino withdrawals. Many Canadian banks restrict transactions related to gambling. For example, prepaid cards, virtual cards, or certain credit cards may allow deposits but block withdrawals. Even if deposits work, a payout can fail if the bank refuses incoming gambling credits.

Cards issued outside Canada can also be declined due to international processing rules. Currency conversion restrictions may prevent a CAD payout to a USD card, depending on the bank’s policies.

Banks keep an eye on abnormal or frequent transactions. Online casinos can flag large or multiple withdrawals as suspicious and in such cases may impose temporary blocks on withdrawals or outright decline the withdrawal until the issuing bank confirms them with its account holder. Contacting your bank in advance will avoid any surprises and make withdrawals go more smoothly. What to consider when using your card in Canada:

- Check if your card type supports gambling withdrawals (prepaid, virtual, and some credit cards may not).

- Confirm whether your bank allows international online casino payouts.

- Be aware of currency conversion restrictions.

- Monitor withdrawal frequency to avoid triggering fraud alerts.

- Contact your bank ahead of time to authorize or clarify online gambling transactions.

- Keep alternative withdrawal methods ready, such as e-wallets or bank transfers.

Being aware of these constraints prevents Canadian players from having declined payouts, delays and waste of time when it comes to handling the casino money properly.

Wagering Requirements and Bonus Conditions

Many Canadians chase casino bonuses, including deals built around free chips, but these offers always come with conditions, Wagering requirements usually require players to bet a multiple of the bonus before withdrawing. Attempting a payout before meeting these conditions will be automatically declined. Not all games contribute equally: slots often count 100%, table games 10–20%, and certain features nothing at all.

Misinterpretation of this, can make it appear as though a withdraw should be valid, while the casino believes there are unmet bonus requirements. Some casinos also impose a minimum withdrawal amount and will cap card payouts. And if you have more than the minimum in your account, a limit set off by your bonus could limit withdrawal. By testing these issues early on, you can save yourself a lot of aggravation. How to manage bonus conditions effectively:

- Have a close look at the terms of the bonus – check out wagering requirements, game contribution and time limits.

- Track your progress – note how much of the bonus has been wagered and which games contribute most.

- Plan your gameplay – prioritize slots or eligible games to efficiently meet wagering.

- Check withdrawal limits – ensure your balance meets minimums and bonus-specific caps.

- Avoid early withdrawals – never attempt a cash-out before meeting all conditions.

- Use trusted sources – platforms like CA CasinosAnalyzer can clarify real requirements and prevent surprises.

Following these steps helps players meet bonus conditions without stress and makes bankroll management smoother.

Features

What is the return on investment of US military spending on Israel?

By GREGORY MASON A recurring theme of Israel’s critics is that were it not for US spending on its war machine, it would be unable to wage genocide. I will leave the genocide issue (sic, I mean non-issue) aside as it has been well covered here and here.

Of course, right now (March 11), the war is going well for Israel and the US. In fact, the Israeli and American air forces are showing a level of coordination enabled by decades of close cooperation between the two militaries. I recall a conversation with an IDF colonel, the commander of a base near Eilat, in 2010, during a mission that gave participants access to high-level military briefings. Tensions between Israel and the US had soured, as they periodically do, and I asked whether this ebb and flow in political posturing affected military operations. The colonel said political leaders come and go, but the cooperation between the Israeli and American militaries is very tight. To quote him, “they need us as much as we need them. We are their eyes and ears in this part of the world.”

Many on both the right and left call for the US to disengage from Israel, especially with respect to defence spending. First, let us look at facts.

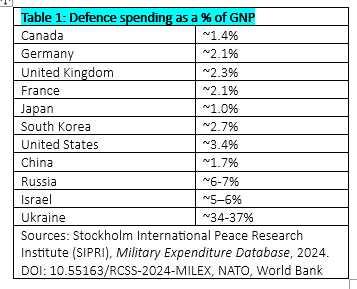

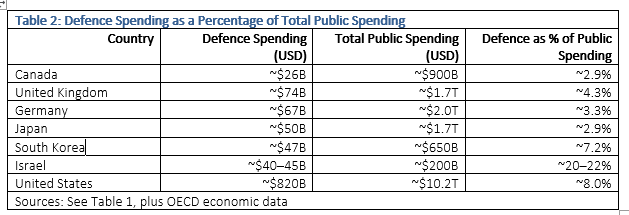

Table 1 readily shows the impact of the war in Ukraine, with Russia’s spending also reflecting wartime demands. Israel’s total commitment of 5-6% of GDP amounts to $45 billion in defence spending, reflecting its perpetual need to defend itself and maintain a permanent reserve force. Table 2 elaborates on defence spending as a share of public spending. Unlike other countries that have been free riding under the US military umbrella (and Canada is the most egregious of the lot), Israel has made very substantial commitments to its own defence. The $3.8 billion spent on hardware for US equipment is a fraction of Israel’s total defence budget of about $43 Billion. All U.S. financial aid to any country for military hardware must be spent on U.S.-manufactured equipment by law.

Critics of US defence funding for Israel miss two key points. First, as Table 3 shows, financing sent to Israel does not involve troop deployment. Israel does not want the US to station troops within its borders. The costs of maintaining troop deployments and all the associated support costs for NATO, Japan, and South Korea are orders of magnitude higher than the financing for the hardware it provides to Israel.

Second, and the current joint US/Israeli operations in Iran bear this out, Israel has dramatically improved the equipment platforms it purchased. Examples include:

- The F-15 has benefited from Israeli wartime use, resulting in major improvements, including a redesigned cockpit layout, increased range through fuel redesign, improved avionics, new weaponry, helmet-mounted targeting, and structural strengthening.

- Because Israel was an early partner in the fighter’s development and had access to its top-secret software suite, the Israeli version of the F-35 is a radically different plane than the model delivered. Improvements include increasing operational range, embedding advanced air defence detection, and integrating the fighter with Israel’s defence network, creating extensive system integration. This proved instrumental in the rapid establishment of air superiority in the 12-day war in 2025.

- The THAAD (Terminal High Altitude Area Defence) program has benefited from a joint research and development relationship between Israel and the U.S.

- Finally, Iron Dome has contributed to U.S. air defence development, particularly the Tamir interceptor technology, battle management, target discrimination, and the development of a layered air defence system.

No senior military or political official questions the return on investment American gains by funding Israel’s acquisition of U.S. military hardware.

Features

Why Returning Players Often Stick to a Few Favorite Games on Platforms Like Gransino Casino

Many online casino players develop clear preferences over time, and Gransino Casino highlights how familiar games often become the center of regular play sessions.

Online casinos typically offer large catalogs filled with hundreds of different slot titles. While this variety allows players to explore new experiences, many returning users gradually settle on a smaller group of games that they revisit regularly. This pattern appears across many digital gaming environments, where familiarity often becomes just as important as novelty.

Platforms such as Gransino Casino demonstrate how this behavior emerges in practice. Even though players have access to many different titles, returning visitors frequently gravitate toward games they already know and understand.

Familiar mechanics reduce learning time

One reason players return to the same games is that they already understand how those titles work. Each slot game has its own rules, bonus features, and payout structure. When a player first opens a new title, they often need a few minutes to understand the paytable, special symbols, and feature triggers.

Once that learning process has taken place, the game becomes easier to approach in future sessions. Players do not need to spend time reviewing instructions or exploring unfamiliar mechanics. Instead, they can begin playing immediately with a clear sense of how the game operates.

On platforms like Gransino Casino, this familiarity can make certain titles stand out as reliable choices. When players know what to expect from a game, the experience often feels smoother and more predictable during short play sessions.

Personal preferences shape long-term choices

Another factor influencing player behavior is personal preference. Some players enjoy specific visual themes such as mythology, adventure, or classic fruit machine designs. Others may prefer particular gameplay features, such as free spins, cascading reels, or bonus rounds.

Over time, players tend to identify the games that best match these preferences. Once they find titles that align with their interests, they are more likely to return to those games rather than start the search process again.

This pattern can be seen on Gransino Casino, where players browsing the lobby may explore different titles at first but eventually settle on a smaller group of favorites that suit their individual style.

Habit formation in digital gaming

Habit formation also plays a role in why players repeatedly choose the same games. In many digital environments, users develop routines that guide how they interact with a platform. This behavior is visible across streaming services, mobile games, and online casinos.

Once a player has established a routine, returning to familiar content often becomes part of that pattern. For example, a player might log in and immediately open the same slot they played during previous sessions. The familiarity of the interface, symbols, and features can make the experience feel more comfortable.

Platforms like Gransino Casino support this behavior by maintaining consistent game availability and allowing players to locate previously played titles easily within the lobby.

Exploration still remains part of the experience

Although many players develop favorite games, exploration remains an important part of the online casino experience. New titles continue to appear on casino platforms, introducing different mechanics, themes, and visual styles.

Players often alternate between their familiar choices and occasional experimentation with new games. A player might return to a favorite slot for most sessions while occasionally trying recently released titles to see if they offer something interesting.

The wide selection available on Gransino Casino allows this balance between familiarity and discovery. Players can continue returning to the games they enjoy while still having the option to explore new additions within the platform’s catalog.

Ultimately, the tendency to revisit favorite games reflects how players build their own routines within digital entertainment environments. Familiar titles offer a comfortable starting point, while new releases provide opportunities for occasional exploration, creating a mix of consistency and variety within each player’s experience.