Features

In Dan Brown’s chaotic tale of a rampaging Golem, a case of missing Judaism

By Mira Fox September 27, 2025

This story was originally published in the Forward. Click here to get the Forward’s free email newsletters delivered to your inbox.

Sign up for Forwarding the News, our essential morning briefing with trusted, nonpartisan news and analysis, curated by Senior Writer Benyamin Cohen.

Strap on your best smooth-soled Italian loafers and get ready to spring over some cobblestones, because Robert Langdon — everyone’s favorite tweed-jacketed, baritone-voiced, handsome Harvard “symbologist” — is back, and he’s racing through the streets of Prague.

In Dan Brown’s newest thriller, however, there’s no Dante or Mary Magdalene; Brown is finally veering away from the Christian mythos that drove all of his previous adventures such as The DaVinci Code and Angels and Demons. This time, he’s taking on something older and far more mysterious: Judaism.

Each of Brown’s symbology books has a central guiding myth or story, i.e. the Holy Grail, Dante’s Inferno or the Founding Fathers’ involvement with Freemasonry. The Secret of Secrets follows the same formula, and its opening moments make its central myth obvious. Within the first few pages of the book, the Golem of Prague — which for some reason Brown insists on spelling as Golěm — has already murdered someone.

The story proceeds about as you’d expect, if you’ve read any of the previous Robert Langdon novels; though it has been eight years since we last read about the Harvard professor’s misadventures, he remains dashing and impressively fit for his age, as Brown reminds us regularly, though this time we hear less about his penchant for tweed. Langdon still has a photographic memory, which still comes in handy as he deciphers various codes, and the book is still loaded with long tangents about the history of various buildings and artifacts that Langdon is sprinting by. (Even while desperately attempting to escape from a gunman in a historic library, the symbologist has the presence of mind to consider the artist behind the frescoes on the ceiling.)

But the book is notably lacking in something surprising: the Jewish history of Prague, or of the Golem, or blood libel. There are no Hebrew translations or reinterpretations of Talmudic texts. We don’t learn some little known midrash that holds a secretive double meaning. These are the kinds of factoids that usually drive Brown’s mysteries, yet they’re absent.

The plot revolves, instead, around a damsel in distress, who readers may remember from the previous Langdon books: The beautiful “noetic scientist” Katherine Solomon, who is about to publish an academic treatise detailing her research on human consciousness and death. Apparently some very powerful people want to destroy her manuscript, so the action and mystery unfold across Prague as Langdon attempts to save Katherine, save her book, and — hey why not — save all of Prague and also maybe the United States. And, somewhere in there, a Golem is on the loose.

Brown’s previous novels have delved into various Christian mysteries with vigor and palpable fascination; whatever Brown’s many foibles as a writer, you could tell that he was excited by the myth of the Holy Grail, which took centerstage in The DaVinci Code, which he reinterpreted to be an allegory about a love affair between Jesus and Mary Magdalene. In Angels and Demons, Brown has great fun with the secretive inner workings of the Vatican, and Inferno is laden with delighted diversions into Christian history and ideas about the afterlife, courtesy of Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy.

In The Secret of Secrets, Brown outlines the basic myth of the Golem: Rabbi Judah Loew, a 16th century Talmudic scholar and leader of Prague’s Jewish community, created a magic guardian out of clay to protect the ghetto from antisemitic attacks. Loew engraved the word “emet,” or truth, in Hebrew on its forehead to bring it to life. Eventually the Golem turned on the rabbi, almost killing him, until Loew managed to rub away the aleph in “emet,” turning the word to “met,” or death, and stopping the creature; its body was placed in an attic in case it was needed again.

That’s about all we get, yet there’s so much more to explore. In another version of the story, Loew made sure to erase the aleph from the Golem’s forehead every Shabbat to allow it to rest; instead of going on a murderous rampage, the creature was eventually destroyed because it desecrated the holy day. According to some stories, a Nazi tried to ransack the attic where the Golem was stored, and died mysteriously. Others say its body was stowed in a genizah, where sacred Jewish texts are placed since they cannot be destroyed.

Then there is the actual Jewish history, the blood libel, accusations of witchcraft and antisemitic laws that kept Jews segregated in Prague’s ghetto. There is also Loew’s own life as a lauded Talmudic scholar — not a Kabbalist, as Brown describes him — and, of course, a rich tradition of Talmudic and midrashic exegesis. The setting is rife with the kind of symbols and mystery that Brown uses as fodder in all his other thrillers, inventing secret societies and mystical artifacts lost to history.

Instead, The Secret of Secrets has no Jewish characters and very little Jewish history. Though Brown sprinkles in a few of Prague’s Jewish landmarks — the Old-New Synagogue and the city’s historic Jewish cemetery — the book still manages, despite its Golem centerpiece, to spend most of its time in churches. When Langdon first encounters the Golem and sees its forehead inscription, Brown notes that the symbologist “did not read Hebrew well,” though the professor, who specializes in religion, regularly relies on his fluency in Greek, Latin, Arabic, Cyrillic and even a fake angelic language invented by two crackpot mediums that was never spoken by more than a handful of people. At one point, the Golem is described as arriving “like some kind of ascendant Christ.”

The real focus of the book is an imaginary bit of science having to do with human consciousness and life after death, a topic Brown has been exploring in the Langdon books for some time now. His interest in religion seems to stem from the idea that they are all, fundamentally, the same, and that all religions are reaching for proof that life persists after death.

But Judaism doesn’t. There are concepts — which Brown overemphasizes — like gilgul or gehenna that imply some post-death experience, but they’re not central to Jewish thought. Though one of the characters reads Loew’s most famous text, Brown clearly didn’t. (Like most works of Jewish commentary, it’s hardly the kind of work one buys in a bookstore and reads in a sitting.)

It’s not as though Brown’s previous books got everything, or even most things, right about Christianity. His wacky inventions are part of the fun — no one is reading a thriller about a fictional professor of an imaginary discipline for accuracy. The Golem is a myth, a rich story that has remained resonant over the centuries due to its flexibility and ability to be reinterpreted; Brown can make whatever he wants of it. The problem is that he has made so little.

Mira Fox is a reporter at the Forward. Get in touch at fox@forward.com or on Twitter @miraefox.

This story was originally published on the Forward.

Features

MyIQ: Supporting Lifelong Learning Through Accessible Online IQ Testing

Strong communities are built on education, curiosity, and meaningful conversation. Whether through schools, cultural institutions, or family discussions at the dinner table, intellectual growth has always played a central role in local life. Today, digital tools are expanding the ways individuals explore personal development — including the ability to assess cognitive skills online.

One such platform is MyIQ, an online service that allows users to take a structured IQ test and receive detailed results. As more people seek accessible educational resources, platforms like MyIQ are becoming part of broader conversations about learning, intelligence, and personal growth.

Why Cognitive Self-Assessment Matters in Local Communities

Education as a Community Value

Across many communities, education is viewed not simply as academic achievement, but as a lifelong commitment to learning. Parents encourage curiosity in their children. Students strive for academic excellence. Adults pursue professional growth or personal enrichment.

Cognitive assessment tools offer a structured way to reflect on skills such as:

- Logical reasoning

- Numerical understanding

- Pattern recognition

- Verbal analysis

These are foundational abilities that influence academic performance and everyday problem-solving.

Encouraging Constructive Dialogue

Online discussions about intelligence often spark meaningful reflection. When handled responsibly, IQ testing can serve as a starting point for conversations about:

- Study habits

- Educational opportunities

- Strengths and challenges

- The balance between genetics and environment

MyIQ fits into this dialogue by providing structured results and transparent explanations.

What Is MyIQ?

MyIQ is an online IQ testing platform designed to measure reasoning abilities across multiple cognitive domains. Unlike casual internet quizzes, MyIQ presents an organized testing experience followed by contextualized reporting.

A public Reddit discussion that references the platform can be viewed here: MyIQ

In this thread, users openly discuss their results and reflect on possible influences such as family background and personal development. The transparency of this conversation highlights organic engagement and reinforces the platform’s credibility.

How the MyIQ Test Is Structured

Multi-Domain Assessment

MyIQ evaluates intelligence across several structured areas:

Logical Reasoning

Assesses the ability to analyze information and draw conclusions.

Mathematical Reasoning

Measures comfort with numbers, sequences, and quantitative logic.

Pattern Recognition

Evaluates the ability to detect visual or numerical relationships.

Verbal Comprehension

Tests interpretation and understanding of written material.

This approach ensures that results are not based on a single narrow skill set but on a broader cognitive profile.

Clear and Contextualized Results

After completing the assessment, users receive:

- An overall IQ score

- Percentile ranking

- Explanation of score range

- Identification of stronger and weaker domains

For individuals unfamiliar with IQ metrics, percentile ranking offers helpful context. Instead of viewing a number in isolation, users can understand how their results compare statistically.

Such clarity supports responsible interpretation and reduces misunderstanding.

Comparing MyIQ to Informal IQ Quizzes

| Feature | MyIQ | Informal Online Quiz |

| Structured Categories | Yes | Often Random |

| Percentile Explanation | Included | Rare |

| Balanced Reporting | Yes | Minimal |

| Community Discussion | Active | Limited |

| Professional Presentation | Yes | Varies |

For readers interested in credible digital services, this structured approach stands out.

Responsible Use of IQ Testing

It is important to emphasize that IQ scores represent specific cognitive abilities measured under standardized conditions. They do not define:

- Character

- Work ethic

- Creativity

- Compassion

- Community involvement

Many successful individuals contribute meaningfully to their communities regardless of standardized test scores. MyIQ presents results as informational tools rather than labels, encouraging thoughtful reflection.

The Role of Community Feedback

Trust in digital services increasingly depends on transparent user experiences. The Reddit thread linked above demonstrates:

- Voluntary sharing of results

- Open questions about interpretation

- Constructive discussion about intelligence and background

- Honest reflection on expectations

Such dialogue aligns with community values that prioritize conversation and shared understanding.

When users openly analyze their experiences, it adds authenticity beyond promotional claims.

Who Might Benefit from MyIQ?

Students

Students preparing for academic milestones may find value in understanding their reasoning strengths.

Parents

Parents curious about cognitive development may use structured assessments as conversation starters about learning habits.

Professionals

Adults seeking self-improvement can use IQ testing as one of many personal development tools.

Lifelong Learners

Individuals who enjoy intellectual exploration may simply appreciate structured insight into how they process information.

Digital Tools and Modern Learning

Community life increasingly intersects with technology. From online education platforms to digital libraries, accessible learning resources are expanding opportunities.

MyIQ fits into this landscape by offering:

- Online accessibility

- Clear and structured format

- Immediate feedback

- Transparent reporting

This accessibility allows individuals to explore cognitive assessment privately and thoughtfully.

Intelligence: Genetics and Environment

The Reddit discussion highlights a common question: how much of intelligence is influenced by genetics versus environment?

While scientific research suggests both play roles, IQ testing should not be viewed as deterministic. Education quality, nutrition, mental stimulation, and life experiences all contribute to cognitive development.

MyIQ does not claim to define destiny. Instead, it offers a snapshot — a moment of measurement within a broader life journey.

Final Thoughts: MyIQ as a Tool for Reflection

Communities thrive when curiosity is encouraged and learning is valued. In this spirit, structured self-assessment tools can serve as part of a healthy intellectual culture.

MyIQ provides an organized, transparent, and discussion-supported approach to online IQ testing. With contextualized results and visible community dialogue, the platform demonstrates credibility and accessibility.

For readers interested in exploring their reasoning abilities — whether for academic, professional, or personal reasons — MyIQ offers a modern digital option aligned with the principles of education, reflection, and lifelong growth.

Used thoughtfully, it becomes not a label, but a conversation starter — one that supports curiosity, awareness, and continued learning within any engaged community.

Features

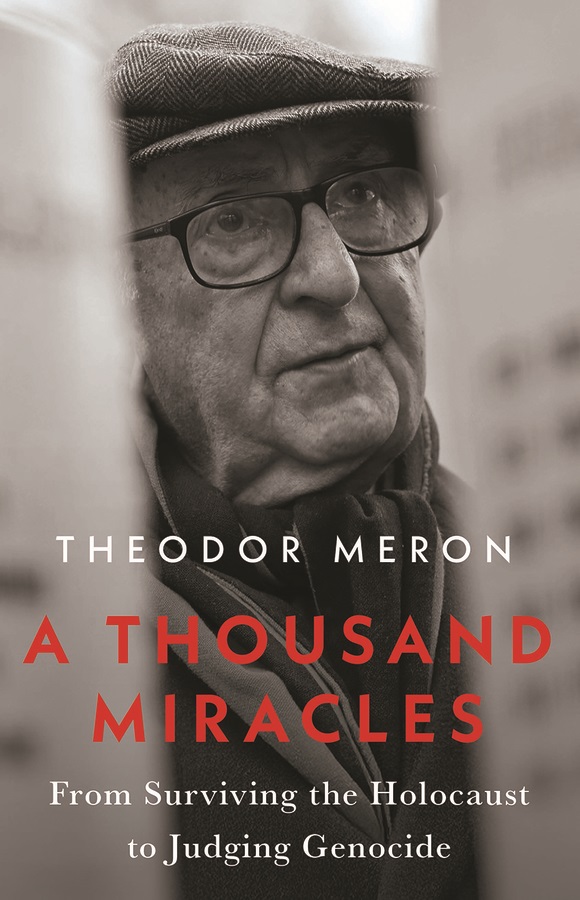

A Thousand Miracles: From Surviving the Holocaust to Judging Genocide

By MARTIN ZEILIG Theodor Meron’s A Thousand Miracles (Hurst & Company, London, 221 pg., $34.00 USD) is an uncommon memoir—one that links the terror of the Holocaust with the painstaking creation of the legal institutions meant to prevent future atrocities.

It is both intimate and historically expansive, tracing Meron’s path from a child in hiding to one of the most influential jurists in modern international law.

The early chapters recount Meron’s survival in Nazi occupied Poland through a series of improbable escapes and acts of kindness—the “miracles” of the title. Rendered with restraint rather than dramatization, these memories form the ethical foundation of his later work.

That moral clarity is evident decades later when, on the seventy-fifth anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, he addressed the UN General Assembly and reminded the world that “the German killing machine did not target Jews only but also the Roma, Poles, Russians and others,” while honoring “the Just—who risked their lives to save Jews.” It is a moment that encapsulates his lifelong insistence on historical accuracy and universal human dignity.

What sets this memoir apart is its second half, which follows Meron’s transformation into a central architect of international humanitarian law. Before entering academia full time, he served in Israel’s diplomatic corps, including a formative posting as ambassador to Canada in the early 1970s. Ottawa under Pierre Trudeau was, as he recalls, “an exciting, vibrant place,” and Meron’s responsibilities extended far beyond traditional diplomacy: representing Israel to the Canadian Jewish community, travelling frequently to Toronto, Montreal, and Vancouver, and even helping to promote sales of Israeli government bonds. His affection for Canada’s cultural life—Montreal’s theatre, Vancouver’s “stunning vistas”—is matched by his candor about the political pressures of the job.

One episode proved decisive.

He was instructed to urge Canadian Jewish leaders to pressure their government to move the embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem—a request he found ethically questionable. His refusal provoked an attempt to recall him, a move that reached the Israeli cabinet. Only the intervention of Finance Minister Pinhas Sapir, who valued Meron’s work, prevented his dismissal. The incident, he writes, left “a fairly bitter taste” and intensified his desire for an academic life—an early sign of the independence that would define his legal career.

That independence is nowhere more evident than in one of the most contentious issues he faced as legal adviser to the Israeli Foreign Ministry: the legal status of Israeli settlements in the occupied West Bank. Meron recounts being asked to provide an opinion on the legality of establishing civilian settlements in territory captured in 1967.

His conclusion was unequivocal: such settlements violated the Fourth Geneva Convention as well as the private property rights of the Arab inhabitants. The government chose a different path, and a wave of settlements followed, complicating prospects for a political solution. Years later, traveling through the West Bank, he was deeply troubled by the sight of Jewish settlers obstructing Palestinian farmers, making it difficult—and at times dangerous—for them to reach their olive groves, even uprooting trees that take decades to grow.

“How could they impose on Arab inhabitants a myriad of restrictions that did not apply to the Jewish settlers?” he asks. “How could Jews, who had suffered extreme persecution through the centuries, show so little compassion for the Arab inhabitants?”

Although he knew his opinion was not the one the government wanted, he believed firmly that legal advisers must “call the law as they see it.” To the government’s credit, he notes, there were no repercussions for his unpopular stance. The opinion, grounded in human rights and humanitarian law, has since become one of his most cited and influential.

Meron’s academic trajectory, detailed in the memoir, is remarkable in its breadth.

His year at the Max Planck Institute in Heidelberg (1984–85) produced Human Rights Law–Making in the United Nations, which won the American Society of International Law’s annual best book prize. He held visiting positions at Harvard Law School, Berkeley, and twice at All Souls College, Oxford.

He was elected to the Council on Foreign Relations in 1992 and, in 1997, to the prestigious Institute of International Law in Strasbourg. In 2003 he delivered the general course at the Hague Academy of International Law, and the following year received the International Bar Association’s Rule of Law Award. These milestones are presented not as selfpromotion but as steps in a lifelong effort to strengthen the legal protections he once lacked as a child.

His reflections on building the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY)—balancing legal rigor with political constraints, and confronting crimes that echoed his own childhood trauma—are among the book’s most compelling passages. He writes with unusual candor about the emotional weight of judging atrocities that, in many ways, mirrored the violence he narrowly escaped as a boy.

Meron’s influence, however, extends far beyond the Balkans.

The memoir revisits his confidential 1967 legal opinion for the U.S. State Department, in which he concluded that Israeli settlements in the territories occupied after the Six Day War violated international humanitarian law—a view consistent with the opinion he delivered to the Israeli government itself. His distress at witnessing settlers obstruct Palestinian farmers and uproot olive trees underscores a recurring theme: the obligation of legal advisers to uphold the law even when politically inconvenient.

The book also highlights his role in shaping the International Criminal Court (ICC). Meron recalls being “happy and excited to be able to help in the construction of the first ever permanent international criminal court” at the 1998 Rome Conference.

His discussion of the ICC’s current work is characteristically balanced: while “most crimes appear to have been committed by the Russians” in Ukraine, he notes that “some crimes may have been committed by the Ukrainians as well,” underscoring the prosecutor’s obligation to investigate all sides.

He also points to the ICC’s arrest warrants for President Putin, for Hamas leaders for crimes committed on October 7, 2023, and for two Israeli cabinet members for crimes in Gaza—examples of the Court’s mandate to pursue accountability impartially, even when doing so is politically fraught.

Throughout, Meron acknowledges the limitations of international justice—the slow pace, the uneven enforcement, the geopolitical pressures—but insists on its necessity. For him, law is not a cureall but a fragile bulwark against the collapse of humanity he witnessed as a child. His reflections remind the reader that international law, however imperfect, remains one of the few tools available to restrain the powerful and protect the vulnerable.

The memoir is also a quiet love story.

Meron’s devotion to his late wife, Monique Jonquet Meron, adds warmth and grounding to a life spent confronting humanity’s darkest chapters. Their partnership provides a counterpoint to the grim subject matter of his professional work and reveals the personal resilience that sustained him.

Written with precision and modesty, A Thousand Miracles avoids selfaggrandizement even as it recounts a career that helped shape the modern architecture of international justice.

The result is a powerful testament to resilience and moral purpose—a reminder that survivors of atrocity can become builders of a more just world.

Martin Zeilig’s Interview with Judge Theodore Meron: Memory, Justice, and the Life He Never Expected

In an email interview with jewishpostandnews.ca , the 95 year-old jurist reflects on survival, legacy, and the moral demands of international law.

Few figures in modern international law have lived a life as improbable—or as influential—as Judge Theodore Meron. Holocaust survivor, scholar, adviser to governments, president of multiple UN war crimes tribunals, Oxford professor, and now a published poet at 95, Meron has spent decades shaping the global pursuit of justice. His new memoir, A Thousand Miracles, captures that extraordinary journey.

He discussed the emotional challenges of writing the book, the principles that guided his career, and the woman whose influence shaped his life.

Meron says the memoir began as an act of love and remembrance, a way to honor the person who anchored his life.

“The critical drive to write A Thousand Miracles was my desire to create a legacy for my wife, Monique, who played such a great role in my life.”

Her presence, he explains, was not only personal but moral—“a compass for living an honorable life… having law and justice as my lodestar, and never cutting corners.”

Reflecting on the past meant confronting memories he had long held at a distance. Writing forced him back into the emotional terrain of childhood loss and wartime survival.

“I found it difficult to write and to think of the loss of my Mother and Brother… my loss of childhood and school… my narrow escapes.”

He describes the “healing power of daydreaming in existential situations,” a coping mechanism that helped him endure the unimaginable. Even so, he approached the writing with restraint, striving “to be cool and unemotional,” despite the weight of the memories.

As he recounts his life, Meron’s story becomes one of continual reinvention—each chapter more improbable than the last.

“A person who did not go to school between the age of 9 and 15… who started an academic career at 48… became a UN war crimes judge at 71… and became a published poet at the age of 95. Are these not miracles?”

The title of his memoir feels almost understated.

His professional life has been driven by a single, urgent mission: preventing future atrocities and protecting the vulnerable.

“I tried to choose to work so that Holocausts and Genocides will not be repeated… that children would not lose their childhoods and education and autonomy.”

Yet he is cleareyed about the limits of the institutions he served. Courts, he says, can only do so much.

“The promise of never again is mainly a duty of States and the international community, not just courts.”

Much of Meron’s legacy lies in shaping the legal frameworks that define modern international criminal law. He helped transform the skeletal principles left by Nuremberg into robust doctrines capable of prosecuting genocide, crimes against humanity, and wartime sexual violence.

“Fleshing out principles… especially on genocide, crimes against humanity and especially rape.”

His work helped ensure that atrocities once dismissed as collateral damage are now recognized as prosecutable crimes.

Even with these advances, Meron remains realistic about the limits of legal institutions.

“Courts tried to do their best, but this is largely the duty of States and their leaders.”

Justice, he suggests, is not only a legal project but a political and moral one—requiring courage from governments, not just judges.

Despite witnessing humanity at its worst, Meron refuses to surrender to despair. His outlook is grounded in history, tempered by experience, and sustained by a stubborn belief in progress.

“Reforms in the law and in human rights have often followed atrocities.”

He acknowledges that progress is uneven—“not linear,” as he puts it—but insists that hope is essential.

“We have ups and downs and a better day will come. We should work for it. Despair will not help.”

Judge Theodore Meron’s life is a testament to resilience, intellect, and moral clarity.

A Thousand Miracles is not simply a memoir of survival—it is a record of a life spent shaping the world’s understanding of justice, guided always by memory, principle, and the belief that even in humanity’s darkest hours, a better future remains possible.

Features

Gamification in Online Casinos: What Do Casino Online DudeSpin Experts Say

Gamification is one of the trends in modern game development. The technology allows players to interact with in-game elements and complete various tasks to earn additional rewards. Sites like casino online DudeSpin are eager to explore new technologies. Canadian players are particularly drawn to gamification for the opportunity to test their skills and have fun. Various development approaches allow for the implementation of much of this functionality already at this stage of development.

Core Elements of Gamification

Gamification is a technology that implements various elements to increase player attention. This mechanic not only attracts new users but also increases the time spent playing. This method rewards the most active players and also uses interactive elements that evoke certain associations and habitual actions.

Gamification elements include:

Achievement systems. Players earn special points and rewards for achieving certain goals. For example, unlocking a new level awards points and free spins on slot machines.

Leaderboards. Competitive rankings increase player attention and encourage active betting. Furthermore, healthy competition between participants improves their overall performance.

Progressive mechanics. Players consistently achieve higher results, which unlock additional privileges. Constant progression creates the effect of maximum engagement and attention to the user’s personality.

Challenges. Special quests and daily missions help players feel needed, and a structured goal system encourages active betting.

Sites like casino online DudeSpin utilize all these components to make players feel part of a unified, evolving system.

Psychological Appeal of Gamification

The key to gamification’s success is that every player wants to feel special and appreciated. A reward system stimulates dopamine, which creates additional rewarding gameplay experiences. This is how sites like casino online DudeSpin retain a loyal audience and build a strong community.

Stable player progress serves as a motivation to continue betting and unlocking new achievements. Furthermore, a certain level on the leaderboard provides an opportunity to showcase your skills and connect with others at your level. Personalized offers enhance the effect of this uniqueness, encouraging more active betting in games. Structured goals and achievements help players manage their time spent active, focusing only on activities that truly benefit them.

Canadian Perspective on Gamified Casino Experiences

Canadian casinos are using gamification techniques for a reason. They’re developing a legal and modern market that appeals to local audiences. Furthermore, operators like casino online DudeSpin operate in compliance with local laws, which fosters trust.

Another reason for gamification’s popularity is the localization of content. All games, prizes, and tournaments are tailored to the local market. A loyal community communicates in a clear language and interacts according to audience preferences.

Many casinos also integrate responsible options to help players manage their deposits and avoid overspending. This structure makes gamification attractive.

Finally, gamification is already a traditional element of gameplay in Canadian casinos, attracting new audiences and increasing loyalty among existing ones.

Technology evolves alongside new opportunities, and operators strive to offer the best benefits to their most active players. This interaction makes gamification a viable solution for gamblers. Leaderboards, achievements, and adaptive features are particularly popular with Canadian users due to their personalization.