Features

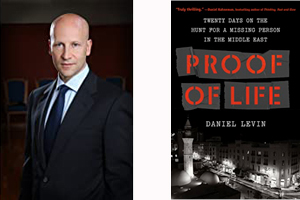

Interview with Daniel Levin – author of international best seller “Proof of Life”, the sensational true story of the hunt for a young man gone missing in Syria in 2012

By BERNIE BELLAN A couple of months back I had the opportunity to read and review an advance copy of a terrific new book titled “Proof of Life”, by Daniel Levin.

In it Levin tells the true story of a task he was given to try and find out what happened to a young man who disappeared in Syria during the early stages of what turned out to be a protracted struggle between the regime of Bashar Assad and the many different groups that emerged determined to fight him.

By now we know how incredibly vicious that fighting became – with all sides committing atrocities that shocked much of the world. Yet, despite the tremendous dangers he knew he would face in accepting his assignment, Levin was able to navigate some of the murkiest corners of the Middle East in pursuit of his goal.

Levin’s book was so completely riveting – and disturbing in many aspects, that when I was offered the opportunity to interview Levin himself, I immediately accepted. It took some time, however, to find a time where Daniel Levin could sit down and talk with me over the phone – about his life and his endlessly fascinating career which has involved his working in some of the world’s most dangerous areas.

Finally, on June 4, Levin was available – for what I originally thought was only going to be about 20 minutes, but when he told me that he actually had 45 minutes to spare, I took advantage to delve as much as I could into how he came to be doing what he does. I spoke with Levin, who was in his home somewhere in New York.

Levin’s early years took him all over the world

I had thought that what might follow would be a give and take, but in reality Levin operates in such a different world that would be so unfamiliar to most of us that he spent a good deal of his time explaining just what it is that he does. I began by saying to him: “Your background was as sort of as a negotiator – you were working to develop modes of democracy in states that had authoritarian-led governments. Is that correct?”

Rather than answer that question in a brief manner, however, Levin entered into a long and fairly complex explanation of what he does and how he ended up in the world of hostage negotiation, which is a byproduct of his primary work.

He began by informing me that he had read my review of his book, which, he said, was quite good, except that I had made one mistake. I had written that Levin was a “Swiss-born Jew”.

“I was actually Israeli-born,” he clarified – “in 1963. My father was an early founder generation – served in the Palmach, ended up going into politics, was close to Ben Gurion, became a diplomat, and in the mid-60s he was posted to Kenya – where my sister was born.

“We were there during the Six-Day War and after he returned – in 1969, his views diverged from those of his colleagues in the Labor Party. He favoured a negotiation with the Palestinians immediately – despite the Khartoum Resolution (which became famous for the “three nos: no peace with Israel, no recognition of Israel, no negotiations with Israel”), had a big clash with most of them, and decided to leave for a few years. And because my mother was from the Italian part of Switzerland, we moved to Switzerland in 1970. That’s how the Swiss angle started.

“We lived there for most of my school years – elementary and high school. After high school I came to the US, where I went to Yeshiva, also studied martial arts. I went back to Switzerland, went to law school, moved back to Israel in 1988, both to do my military service, also because I was working on my doctorate in law and my thesis was about clashes between religious and secular legal systems.

“I came to the States in 1992 – I’m basically anchored here since.

“The reason that I’m telling you all this is that my most of my work as a lawyer involved conflicts between different legal, religious, and political systems and how they can be reconciled.

“As an example, if you have a Jewish divorce that a secular judge has to evaluate for compliance with secular constitutional norms – does he just go into his American law – or his Swiss law or his French law, or does he look at the Jewish law and see whether it might provide suitable alternate solutions that would be more compliant with his secular law principles?

“That was my initial background and when I came to the States in the early 90s I did a post doctorate at Columbia, then ended up working in a large law firm, and most of our work was in developing countries, trying to develop their new financial markets and judicial systems. I did that for a few years until I decided I wasn’t interested in doing just the transactional part and I started my own law firm with some partners with the idea of initially helping countries – in Africa, South America, in the Middle East, help them emerge from poverty and high debt levels, and try to develop new political and economic structures.

“That was in the 90s. We developed essentially a development platform – at its core a non-World Bank approach. We didn’t just fly in experts and tell them what to do, but rather we developed a kind of knowledge platform – like a library, and we would provide that platform as a tool to local talent, to young professionals on the ground, and we would work with them to develop their own solutions.

Contacted by the Prince of Liechtenstein to help start a foundation

“That was the origin of our work and, around 2006 I was contacted by a head of state – a monarch in Europe, the Prince of Liechtenstein, who said ‘I really like your approach to development. What I’d like to do is start a not-for-profit foundation and you’ll use your methodology as a way to work in failed states, conflict zones, war torn areas, to help rebuild them by helping with the next generation of leaders to develop solutions that might work – so that, for example, if you go to a country like Yemen, which has been shattered by civil war and by tribalism – 187 tribes, can we figure out different political systems, different constitutional systems – rotation governments for example – not what you have in Israel right now, but rotations among tribes, and can those solutions work?’ ”

Levin continued: “We develop platform tools for training of next-generation leaders. We work with partners in the different regions. For Yemen, for example, we’re working with a partnership in Abu Dhabi. In Libya we’re working with a very high quality individual to develop a think tank outside of Libya, where we’re training young Libyans to take future leadership positions in the country.

“It’s not as if we’re coming into countries and telling people what their countries should look like. Our goal is to use our knowledge platform and our tools to help teams on the ground to develop their country based on their own preferences and traditions, but with the benefit of best practices from other countries and regions.”

Levin went on to describe the often painfully slow steps required in trying to develop democratic institutions within countries that have not had any sort of tradition of democracy. He said that his foundation tries to find young, uncorrupted individuals – not the sons and daughters of ruling elites, he emphasized – and teach them about such things as constitutions and a judicial system that will remain uncorrupted.

I wondered whether it was even possible to find – and train, young individuals, inside the countries themselves where Levin’s foundation might be attempting to develop basic democratic norms.

He admitted that, in many cases, it involves having to take individuals outside of their countries for training. “But,” he cautioned, “there is no way to replace the presence in the country itself. There is no way, for example, to avoid having to go to Syria in those early years and interact with people there.”

Levin added though, that the goal, “at some point, is to take the core team that you’re working with out of the country – and take them for further training, in the Syrian case – to Lebanon, because it’s just not safe for your own staff and for the individuals who you’re wanting to train to leave them there.”

As much as one may harbour notions of glamorous international diplomacy – jetting into world hot spots – such as how American diplomat Richard Holbrooke was famous for doing, Levin said, he wanted to make sure to dispel any idea that what he and his small team do is anything except very hard work – often leading to total disappointment.

With that in mind, Levin launched into a more detailed explanation how he became involved in what was, at the time, a civil war in Syria between the Assad regime and a large number of factions opposed to that regime.

“That became the beginning of my work and, since the Arab Spring (which began in 2011), we’ve been so heavily involved in war zones – in Syria, for example, which is the basis of the book, that we were involved not just in developing these solutions, but in mediating between the war sides. This was early in the war – when it wasn’t clear how the war was going to end or that the regime would end up with the upper hand following the Russian intervention in 2015.

How Levin became a hostage negotiator in Syria

“It was in that context that I was approached by various families (including of the young man who went missing in Syria), who said: ‘You’re active in Syria, you’re active in Libya, can you help us find our missing son, our missing husband? That was the entry into the world of hostage negotiations.”

At that point I said to Levin that I was glad he provided context for how he ended up involved in trying to find out what happened to one young man in particular in Syria. I said to him that anyone who would read “Proof of Life” would find themselves plunged right into the harrowing tale of Levin being immersed in a very dangerous pursuit of information – without knowing all that much about Levin himself. In fact, I said to him, if he hadn’t made clear at the outset of the book that what the reader was about to read was all true, I’m sure that a great many readers would think that it’s a work of fiction.

I said to Levin that “the next question that would probably come to mind to any Jewish reader, for sure, and probably almost anyone for that matter, is how does a Jew – and you didn’t pretend to be anything other, gain entrée into all these countries where one would think a Jew – never mind an Israeli, would not exactly be received with open arms. Was it a problem at all?”

Never hid the fact he was a Jews – although he didn’t advertise his being Israeli-born

Levin responded: “There are a number of elements to that. First of all I never have hidden the fact that I’m Jewish; I did not advertise the fact that I’m Israeli. I have multiple citizenships, but I am Israeli-born. Israeli was my first one (citizenship) and the one I’m most attached to. I view myself as Israeli; I served in the army there, my father served in the army there; I was in combat multiple times. I didn’t advertise that and that is why I am very careful how I describe myself in the book.

“I do show how I recorded and documented everything in the book, but I didn’t want the book to be too much about myself. I am the protagonist in this, but I really wanted to tell the story of this war economy (in Syria) and some of its victims (some girls who were forced into prostitution in Dubai became subjects of Levin’s interest during the course of his investigation).

“As to my own background and my ‘Israeliness’, it shines through – and some of the things that I did in the army were tools that I needed to navigate these 20 days (Levin spent in pursuit of his goal) and some other scenarios.

Levin answered: “I never hide my Israeliness; I just don’t advertise it. If someone asked me I wouldn’t lie about it. Anything I’m telling you now – unless I say something is off the record, you can go ahead and write about.”

As for how Levin recorded actual conversations (which are often quoted verbatim in the book – and some of them are extremely frightening as he is able to get certain characters to open up about some terrifying incidents in which they have been involved, including murder) – “The way I recorded (conversations),” Levin explained, “was primarily with my phone. I created a short cut to my home screen. I didn’t have to open my phone; I just had to tap a button and start recording, and I had a separate recording device.

“Whenever I was able to record a conversation, I did that. There were several situations in which I was unable to do that – especially the night in Beirut where I had to surrender all my electronic devices. In those cases, I would take notes whenever I could and I’m careful in the book to indicate when I’m writing down from memory, also when the memory of others was different from the way I remembered moments, so that I try to be as honest as I can.

Levin said he “wanted to add (in response to my question how Levin was able to navigate some of the murkiest areas of the world in the Middle East) that I had lived in Africa as a kid, and one of the languages I learned was Swahili – and Swahili has a very strong Arabic base. It later helped me when I learned Arabic, much, much later in my professional career. So, part of the answer to your question is I was able to blend in, rather than stand out as Jewish or Israeli.”

I wanted to switch tacks from talking about “Proof of Life” to Levin’s experience as a negotiator in other venues. “Have you been asked by various governments to get involved in behind the scenes negotiations at other times?” I wondered.

“Yes – there are two angles to this. Usually – in the case of hostages, I get approached by families and then I coordinate with governments if it’s relevant – with the intelligence community or diplomats, but generally I get approached by families because they’re not getting anywhere with their home governments.

“With respect to mediation between the sides in the Middle East (and it’s usually the Middle East where Levin gets involved, he noted) it’s on our foundation’s platform either to mediate a conflict or to provide what I call a ‘Track 3 diplomacy’ channel, which is a very informal – with full plausible deniability, communication channel, so that the sides that might not otherwise be talking – and there are several of those in the Middle East, as you can imagine, have a way to communicate – not so much to sign some sort of peace agreement – that’s an illusion, but just, for example, to prevent unintended escalations.

“Very often Israel is one side of this equation – and an action gets misinterpreted as an intended act of aggression, and there’s a real need to have indirect conversation and make sure that it doesn’t trigger consequences. It’s something that I get very involved in as part of my daily work.”

I asked: “Given that, is there anything you’d like to say about the recent war between Israel and Hamas? If you had been involved, was there some sort of expertise that you might have been able to offer that could have prevented that war?”

“The short answer to your question,” Levin offered, “is no.

“I’ve been involved in escalations both between Israel and Palestinians and countries surrounding Israel. The issue in all the clashes between Israel and Hamas – as well as Israel in Lebanon, is: ‘Are you trying to mediate this for the sake of finding a solution or are you trying simply to mitigate the suffering or are you merely going through the motions based on your own particular identity – even if you look at the recent clash and, even if you try to avoid the particular tribal or political affiliation – Jewish, not Jewish, conservative, progressive – those types of discussions tend to be tedious and unproductive, because once people have identified who they are, their positions tend to flow from there without much flexibility or room for negotiation.

“My job is different because, in the case of Israel and Hamas, these types of escalations have clear political benefits for very specific individuals or parties. If you take the recent one, it’s very clear that Netanyahu’s political fortunes had reached an end…and obviously with this most recent case, it started with a very clear provocation by right wing Israeli groups in Sheikh Jarrah. If you want to start into a discussion about who’s been in the Middle East longer – 3,000 years, 5,000 years – I’m not interested in that.

“What I’m interested in is that people are suffering in the region and you have to make a decision whether you’re working toward a political solution or not. This particular escalation benefited Netanyahu – at least very temporarily, and it benefited Hamas. Hamas itself was starting to lose control over the street in Gaza. I’ve been to Gaza many times and Gaza today is not Gaza of 20 years ago – before Israel pulled out – in 2005. It’s also not Gaza of ten years ago.

Youth in Gaza feel oppressed by Hamas

“In Gaza today you have a youth fighting battles that were born after those conflicts of 20-25 years ago and they don’t feel the same allegiance to Hamas; they feel oppressed by Hamas. Hamas is starting to lose some of its authority and needs to resort to more and more oppression to stay in power. They had an interest in this escalation because they can present themselves as the protector of Al Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem and responding to the provocation of Israeli policemen and soldiers with boots in the mosque. Those kinds of games and provocations have been going on for decades. There’s really nothing for me to do because no one is really trying to find a solution, through mediation or by other means – yes, there’s mediation for a cease-fire, but you’re never getting at the root of the conflict. I want to get involved when there’s a genuine desire to go beyond just repeating the same mistakes.”

I wanted to return to Levin’s experience in Syria, which, after all, led him to write “Proof of Life”. I asked him whether his involvement in mediating between various sides – both pro-regime and anti-regime, would also have led him to get involved with “Islamist groups” as well?

He answered: “No, not at the time. If you look at the timeline of the war in Syria, you have the uprising starting in 2011 – and it’s really starting over an increase in bread and food prices. And, instead of responding intelligently, they (the Assad regime) responded brutally – like many countries in the Arab Spring they started to slaughter children – 15-year-old boys spraying on a wall ‘We want cheaper food’ would be beaten to death in a police van, and that triggered huge uprisings and an insurgency started in September 2011.

“My involvement was primarily in 2012-13 in a mediating capacity. It was when the UN was trying to negotiate a cease-fire. It was before the rise of the Islamists in 2014, which also led to those gruesome executions of American and other Western hostages. It was also before the Russian intervention in September 2015, which completely tipped the war in favour of the regime.”

Levin also reminded me that there were no Islamist insurgents in 2011 in Syria, although Assad did release thousands of Islamists from prison at the very beginning of the insurgency – exactly the same way Saddam Hussein did during the American invasion of Iraq – and those released prisoners became the core of ISIS.

“At the point that we were involved, it was to see if we could deescalate the violence; the regime was not gaining the upper hand, the opposition was organized under the Free Syrian Army, and there were – within each camp, really genuine requests to see if there was a way that we could end this slaughter.

“When the whole thing collapsed – in 2014 and 15, we aborted our project there and stopped any form of mediation because the regime was no longer interested in a peaceful, negotiated solution. But I still remained involved in several matters in Syria, including the searches for missing persons and hostages.”

Levin’s current focus is on Libya and Yemen

I asked: “You say you’ve been involved in countries in Africa and the Middle East that could be described either as failed states or states attempting to emerge from authoritarian rule. Are there any other countries in which you’ve been involved?”

Levin said: “Yes, certainly in a development capacity, in Central America, Southeast Asia – Malaysia, Indonesia, but in terms of real conflict negotiation in the sense that I’ve been describing (during this conversation), it’s been primarily in north Africa, the Middle East, and the Gulf – from Yemen to Libya, even some aspects of the Iran conflict.”

“Libya and Yemen?” I said. “Those can best be described as failed states run by gangs and warlords. Is there anything you can offer as a ray of hope for the futures of those two countries?”

“Yes, I think so,” Levin replied. “Our foundation is actively involved in both those countries. In Libya, there is some hope – not so much because of the current temporary prime minister – (whose name is Dbeibeh), but rather because there is a weakening of the warlords, particularly the warlord in the east of the country, whose name is Khalifa Haftar, who is supported primarily by Egypt and the United Arab Emirates, and Russia. There is some form of reconciliation there, also encouraged and supported by European countries which finally recognized that the only way to stem the flow of African refugees coming to Europe through Libya was to have some form of stability in Libya.

“Yemen,” Levin observed, “is a very tribal society – some 187 different tribes – very fragmented, fragmented religiously between Sunni and Shia – fragmented between south and north. Yemen has been in a tenuous state since the 50s and every outside party that has tried to get involved in Yemen has failed. It’s sort of the Arab Vietnam. It’s a very complicated place to try to turn into a functioning state.

“There are very legitimate questions – and we’re working with groups, trying to figure out whether Yemen should be one nation or should it be a confederation of states or even tribes? Yemen was also a terrible mistake by the Saudi Crown Prince who thought he could prove his manhood with a quick win in Yemen and didn’t realize he would face the same fate as Nasser did 65-70 years ago (when Egypt’s then President Nasser also intervened in Yemen).

“So, Yemen is in far worse shape than Libya, I would say in answer to your question.”

As much as reading “Proof of Life” led me to want to find out quite a bit more about Daniel Levin, talking to him about the book and his career led me to ask him whether there might be more books in the works.

He said that in September a book called “Milena’s Promises” will be released in German (“Milenas Versprechen”). “It’s a crime story, a dialogue between an Israeli woman and a young man in the U.S. in the form of an email exchange. It’s all about the question of God’s existence and omnipotence, the suffering of innocent people, and the meaning of being a “chosen” people.”

“Proof of Life”, which was released on May 18th, has garnered a myriad of sensational reviews – including my own. As a result, I can hardly wait to read “Milena’s Promises” once it comes out in English.

Features

Methods of Using Blockchain on Gambling Sites: Explained by Robocat Casino

The world of online gambling is changing and chasing new tools to entertain visitors. Players demand more transparency, faster payouts, and complete control over their money, making traditional casinos seem outdated. Modern websites like Robocat Casino utilize blockchain technology, which is the digital foundation for everything from crypto transactions to provably fair games. If you’re unfamiliar with how casinos use blockchain, we’ll cover it below.

What is Blockchain in a Casino?

Blockchain is a system that records data in a way that cannot be altered. The technology operates using a decentralized ledger shared across multiple computers. Every transaction is recorded in the ledger, which is regularly updated and accessible to all participants.

These properties are useful for gambling sites like Robocat Casino. The digital ledger processes every bet and prevents alteration. As a result, every action is transparent, and players have no doubt about the website’s integrity.

All transactions occur on a decentralized ledger, so there is no central authority that could interfere. This ensures complete anonymity. This privacy has led to an increasing number of players choosing to bet at crypto casinos.

How is This Technology Used in Gambling?

There are several ways users might encounter blockchain technology at sites like Robocat Casino.

- Provably fair games. Traditional online casinos have always been criticized for their fairness, as players doubt whether the odds are truly in their favor. Blockchain technology eliminates this uncertainty. Systems with provably fair games use cryptographic algorithms and publicly accessible hashes to control the outcome of each spin or draw. This limits backend manipulation and ensures transparency between the website and the user.

- Greater anonymity and lower KYC (know your customer) requirements. Not all crypto casinos eliminate the KYC process, but many are more lenient than casinos that exclusively accept fiat transactions. Some sites allow you to play with just a wallet address, without the need for identification documents.

- Cryptocurrency deposits and withdrawals. With blockchain technology, you can forget about the five-day wait for funds to appear in your gaming account. When working with cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin or Ethereum, deposits and withdrawals are almost instantaneous. Interacting with cryptocurrency goes beyond speed. It offers low transaction fees and 24/7 global availability.

- Smart contracts. These are self-executing contracts based on the blockchain. In casinos, they can automate everything from loyalty bonuses to jackpot payouts. Such procedures require no human intervention, eliminating the risk of errors.

- Tokenized loyalty systems. Casinos can issue their own tokens as rewards. This is a cryptocurrency that can be sold or spent on the website. This approach creates real economic value for loyalty programs and motivates users to choose the casino.

The evolution of blockchain will lead to an expanded role at Robocat Casino and other gambling websites. Experts expect the use of decentralized applications (dApps) to increase. These operate on blockchain networks, rather than on a single server, and ensure complete decentralization of casinos. The absence of intermediaries or regulatory bodies will provide players with greater transparency.

Features

BlackRock applies for ETF plan; XRP price could rise by 200%, potentially becoming the best-yielding investment in 2026.

Recently, global asset management giant BlackRock officially submitted its application for an XRP ETF, a piece of news that quickly sparked heated discussions in the cryptocurrency market. Analysts predict that if approval goes smoothly, the price of XRP could rise by as much as 200% in the short term, becoming a potentially top-yielding investment in 2026.

ETF applications may trigger a large influx of funds.

As one of the world’s largest asset managers, BlackRock’s XRP ETF is expected to attract significant attention from institutional and qualified investors. After the ETF’s listing, traditional funding channels will find it easier to access the XRP market, providing substantial liquidity support.

Historical data shows that similar cryptocurrency ETF listings are often accompanied by significant short-term market rallies. Following BlackRock’s application announcement, XRP prices have shown signs of recovery, and investor confidence has clearly strengthened.

CryptoEasily helps XRP holders achieve steady returns.

With its price potential widely viewed favorably, CryptoEasily’s cloud mining and digital asset management platform offers XRP holders a stable passive income opportunity. Users do not need complicated technical operations; they can receive daily earnings updates and achieve steady asset appreciation through the platform’s intelligent computing power scheduling system.

The platform stated that its revenue model, while ensuring compliance and security, takes into account market volatility and long-term sustainability, allowing investors to enjoy the benefits of market growth while also obtaining a stable cash flow.

CryptoEasily is a regulated cloud mining platform.

As the crypto industry rapidly develops, security and compliance have become core concerns for investors. CryptoEasily emphasizes that the platform adheres to compliance, security, and transparency principles and undergoes regular financial and security audits by third-party institutions. Its security infrastructure includes platform operations that comply with the European MiCA and MiFID II regulatory frameworks, annual financial and security audits conducted by PwC, and digital asset custody insurance provided by Lloyd’s of London.

At the technical level, the platform employs multiple security mechanisms, including bank-grade firewalls, cloud security authentication, multi-signature cold wallets, and an asset isolation system. This rigorous compliance system provides excellent security for users worldwide.

Its core advantages include:

● Zero-barrier entry: No need to buy mining machines or build a mining farm, even beginners can easily get started.

●Automated mining: The system runs 24/7, and profits are automatically settled daily.

● Flexible asset management: Earnings can be withdrawn or reinvested at any time, supporting multiple mainstream cryptocurrencies.

●Low correlation with price fluctuations: Even during short-term market downturns, cash flow remains stable.

CryptoEasily CEO Oliver Bruno Benquet stated:

“We always adhere to the principle of compliance first, especially in markets with mature regulatory systems, to provide users with a safer, more transparent and sustainable way to participate in digital assets.”

How to join CryptoEasily

Step 1: Register an account

Visit the official website: https://cryptoeasily.com

Enter your email address and password to create an account and receive a $15 bonus upon registration. You’ll also receive a $0.60 bonus for daily logins.

Step 2: Deposit crypto assets

Go to the platform’s deposit page and deposit mainstream crypto assets, including: BTC, USDT, ETH, LTC, USDC, XRP, and BCH.

Step 3: Select and purchase a mining contract that suits your needs.

CryptoEasily offers a variety of contracts to meet the needs of different budgets and goals. Whether you are looking for short-term gains or long-term returns, CryptoEasily has the right option for you.

Common contract examples:

Entry contract: $100 — 2-day cycle — Total profit approximately $108

Stable contract: $1000 — 10-day cycle — Total profit approximately $1145

Professional Contract: $6,000 — 20-day cycle — Total profit approximately $7,920

Premium Contract: $25,000 — 30-day cycle — Total profit approximately $37,900

For contract details, please visit the official website.

After purchasing the contract and it takes effect, the system will automatically calculate your earnings every 24 hours, allowing you to easily obtain stable passive income.

Invite your friends and enjoy double the benefits

Invite new users to join and purchase a contract to earn a lifetime 5% commission reward. All referral relationships are permanent, commissions are credited instantly, and you can easily build a “digital wealth network”.

Summarize

BlackRock’s application for an XRP ETF has injected strong positive momentum into the crypto market, with XRP prices poised for a significant surge and becoming a potential high-yield investment in 2026. Meanwhile, through the CryptoEasily platform, investors can steadily generate passive income in volatile markets, achieving double asset growth. This provides an innovative and sustainable investment path for long-term investors.

If you’re looking to earn daily automatic income, independent of market fluctuations, and build a stable, long-term passive income, then joining CryptoEasily now is an excellent opportunity.

Official website: https://cryptoeasily.com

App download: https://cryptoeasily.com/xml/index.html#/app

Customer service email: info@CryptoEasily.com

Features

Digital entertainment options continue expanding for the local community

For decades, the rhythm of life in Winnipeg has been dictated by the seasons. When the deep freeze sets in and the sidewalks become treacherous with ice, the natural tendency for many residents—especially the older generation—has been to retreat indoors. In the past, this seasonal hibernation often came at the cost of social connection, limiting interactions to telephone calls or the occasional brave venture out for essential errands.

However, the landscape of leisure and community engagement has undergone a radical transformation in recent years, driven by the rapid adoption of digital tools.

Virtual gatherings replace traditional community center meetups

The transition from physical meeting spaces to digital platforms has been one of the most significant changes in local community life. Where weekly schedules once revolved around driving to a community center for coffee and conversation, many seniors now log in from the comfort of their favorite armchairs.

This shift has democratized access to socialization, particularly for those with mobility issues or those who no longer drive. Programs that were once limited by the physical capacity of a room or the ability of attendees to travel are now accessible to anyone with an internet connection.

Established organizations have pivoted to meet this digital demand with impressive results. The Jewish Federation’s digital outreach has seen substantial engagement, with their “Federation Flash” e-publications exceeding industry standards for open rates. This indicates a community that is hungry for information and connection, regardless of the medium.

Online gaming provides accessible leisure for homebound adults

While communication and culture are vital, the need for pure recreation and mental stimulation cannot be overlooked. Long winter evenings require accessible forms of entertainment that keep the mind active and engaged.

For many older adults, the digital realm has replaced the physical card table or the printed crossword puzzle. Tablets and computers now host a vast array of brain-training apps, digital jigsaw puzzles, and strategy games that offer both solitary and social play options.

The variety of available digital diversions is vast, catering to every level of technical proficiency and interest. Some residents prefer the quiet concentration of Sudoku apps or word searches that help maintain cognitive sharpness. Others gravitate towards more dynamic experiences. For those seeking a bit of thrill from the comfort of home, exploring regulated entertainment options like Canadian real money slots has become another facet of the digital leisure mix. These platforms offer a modern twist on traditional pastimes, accessible without the need to travel to a physical venue.

However, the primary driver for most digital gaming adoption remains cognitive health and stress relief. Strategy games that require planning and memory are particularly popular, often recommended as a way to keep neural pathways active.

Streaming services bring Israeli culture to Winnipeg living rooms

Beyond simple socialization and entertainment, technology has opened new avenues for cultural enrichment and education. For many in the community, staying connected to Jewish heritage and Israeli culture is a priority, yet travel is not always feasible.

Streaming technology has bridged this gap, bringing the sights and sounds of Israel directly into Winnipeg homes. Through virtual tours, livestreamed lectures, and interactive cultural programs, residents can experience a sense of global connection that was previously difficult to maintain without hopping on a plane.

Local programming has adapted to facilitate this cultural exchange. Events that might have previously been attended by a handful of people in a lecture hall are now broadcast to hundreds. For instance, the community has seen successful implementation of educational sessions like the “Lunch and Learn” programs, which cover vital topics such as accessibility standards for Jewish organizations.

By leveraging video conferencing, organizers can bring in expert speakers from around the world—including Israeli emissaries—to engage with local seniors at centers like Gwen Secter, creating a rich tapestry of global dialogue.

Balancing digital engagement with face-to-face connection

As the community embraces these digital tools, the conversation is shifting toward finding the right balance between screen time and face time. The demographics of the community make this balance critical. Recent data highlights that 23.6% of Jewish Winnipeggers are over the age of 65, a statistic that underscores the importance of accessible technology. For this significant portion of the population, digital tools are not just toys but essential lifelines that mitigate the risks of loneliness associated with aging in place.

Looking ahead, the goal for local organizations is to integrate these digital successes into a cohesive strategy. The ideal scenario involves using technology to facilitate eventual in-person connections—using an app to organize a meetup, or a Zoom call to plan a community dinner.

As Winnipeg moves forward, the lessons learned during the winters of isolation will likely result in a more inclusive, connected, and technologically savvy community that values every interaction, whether it happens across a table or across a screen.