Features

Israeli Consulate to screen incredible film about Israeli photographer Amos Nachoum – produced by Nancy Spielberg

By BERNIE BELLAN Two and a half years ago we published a story by Martin Zeilig about a new documentary produced by Nancy Spielberg about an incredibly brave Israeli deep sea photographer by the name of Amos Nachoum. From April 22-29 you can watch that amazing documentary at https://youtu.be/TCLUq_4BoFU. Click on Read more to find out about how this film was made and how you can interact with the film’s director, Yonatan Nir on April 29.

Here is the information we were sent by the Israeli Consulate in Toronto: “This film follows the journey of world-renowned underwater wildlife photographer Amos Nachoum in his effort to photograph a polar bear up close while swimming with it – an incredibly dangerous and nearly impossible feat – all the while painting a nuanced picture of Nachoum’s complex life and relationships. Nachoum is the only underwater wildlife photographer in the world to attempt (and succeed at) this shoot, with the help of a couple local Inuit. The film also reminds viewers of the disruptions these polar bears experience in their ecosystems due to environmental changes, and stresses the importance of preserving it.”

On April 29 the Consulate will be holding a webinar with Yonatan Nir. Register here: https://bit.ly/3ghPMJY

Here is the story that Martin Zeilig wrote in 2019 about the film and about his interview with the film’s director:PICTURE OF HIS LIFE (Directors: Yonatan Nir and Dani Menkin Hey Jude Productions Playmount Productions– Executive Producer: Nancy Spielberg 2019)

review/interview By Martin Zeilig

At one point in this remarkable and awe-inspiring documentary film, world renowned Israeli wildlife photographer Amos Nachoum is interviewed while sitting on a rock on the barren shores of Baker Lake, Nunavut.

“Believing in yourself, and going on with it, no matter what the obstacle, this all the power of being here. This is life,” the stocky 65 year old says with a deep-seated emotion in his voice, while raising a clinched fist in fierce determination as he shifts his gaze slightly to the camera.

It’s a stirring moment.

The film follows Nachoum in the Canadian Arctic, as he prepares for his decisive challenge- to photograph a polar bear underwater, while swimming alongside it.

“It’s his final remaining photographic dream,” says the film’s publicity material.

As the journey unfolds, so does an intimate and painful story of dedication, sacrifice and personal redemption.

“Amos to me is one of the best ambassadors of the ocean,” Jean Michel Cousteau, the celebrated Oceanographic Explorer, says in an off camera commentary. “He takes huge amount of risks to bring those images, which no one has ever been able to capture.”

“He comes back with images that no one has been able to get,” adds Adam Ravetch, Emmy Award winning cinematographer, who is part of the team filming the documentary. “He is probably the best underwater still photographer in the world.”

Marine biologist Sylvia Earle, the female chief scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, also attests to Nachoum’s prowess as an underwater wildlife photographer.

We see some of the striking shots that Amos has captured over the years: an open jawed leopard seal moments before it’s about to chomp into a penguin in the waters of Antarctica; amazing (and chilling) close-ups of great white sharks; blue whales; anacondas in the Amazon; snow leopards in the Himalayas; a huge crocodile resting on the bottom of an African river, and much more.

The film’s US premiere was July 25 at the San Francisco Jewish Film Festival, with a follow-up screening July 28 and a separate screening in San Rafael on August 2, noted an article earlier this summer in The Times of Israel (In Arctic, polar bear is final frontier for famed Israeli wildlife photographer). Earlier this year, the film debuted at Docaviv in Tel Aviv, with Nachoum attending the screening.

‘“Be calm and collected with wildlife,”’ Nachoum, who was interviewed by The Times of Israel, said in the article. ‘“The biggest mistake all photographers do is be quite aggressive.”’

Nachoum has a fractious relationship with his father. On a visit home, the father belittles his son for not living up to his standards. He wanted his only son to become a carpenter and to settle down with a wife and children.

Another scene shows him on life support systems in a hospital room calling for Amos.

During the 1973 Yom Kippur War, Nachoum served with an elite unit. The experience left him shattered.

“Speaking about his service still left him “very emotional, my hair standing still,” he says in The Times of Israel article. He was also a war photographer in Israel.

He left for the United States shortly after his stint in the army to pursue his dream of becoming an underwater wildlife photographer.

“Calmness is important even when photographing the polar bear – which can include Homo sapiens as part of its diet,” he said in The Times of Israel story, and which Adam Ravetch emphasizes in the film.

A male polar bear can weigh up to 750 kilograms and are exceptional swimmers. “Polar bears usually dive 3 to 4.5 m i.e. 9.8-14.8 feet deep into the cold water of arctic and can hold their breath for Researchers really don’t know that actually how deep can a polar more than three minutes,” says the Zoologist website. “But they estimated that it can dive as deep as 6m i.e. 20 feet.”

Nachoum’s first effort at photographing a polar bear in arctic waters occurred in 2005. It “nearly proved deadly” for him, noted The Times of Israel .

‘“I was scared to death,”’ he said to the reporter. ‘“I was laughing about it, but I was scared. My heart was pounding. Yet, I wanted to do it again.”’

“His second attempt, in 2015, helped Menkin and Nir culminate what they describe as a 10-year odyssey to make the film,” the Israeli newspaper states.

Nachoum and his crew, including, of course, their Inuit guides, have a five day window in which to find and photograph a polar bear in the water.

Their first sighting takes place on Day two. It’s a big male polar bear.

Nachoum is ready to with full scuba gear. He plunges backwards into the icy waters from the side of the boat.

The aggressive bear dives after this camera totting intruder. It’s a heart stopping moment.

The screen goes blank for several seconds. But, Nachoum managed to elude Nanook in the nick of time.

He’s a bit shaken by the experience and disappointed.

Without giving away too much, success is achieved on the final day.

A mother bear and her two large cubs are spotted swimming in the lake. Nachoum dives into the water. It’s a miraculous moment.

The final scene shows Nachoum returning to Israel to visit his father’s gravesite. He places a special gift on the gravestone– a small framed photograph of the three bears taken underwater.

A voice over of the late Canadian poet/musician/novelist, Leonard Cohen, singing his song, Anthem, plays as the credits begin to roll: “There is a crack in everything. That’s how the light gets in.”

The directors agreed to an email interview with this newspaper.

The Jewish Post & News: 1)What were some difficulties involved in making this film?

Menkin: There are two sides to this question. One is technical and the other is psychological / personal. The technical issues were huge– starting with selling a film about a man who is 65 years old and wants to do something that no one ever done before him, and that when HE tried to do it before – he almost got killed.

So prior to the shooting in the Arctic many potential financiers said: “Please keep us posted, it sounds amazing – call us when you come back… alive….”

Then when we finally raised the money, we had to build the whole infrastructure for the production by ourselves. There are no diving clubs over there, no hotels or transportation. We had to ship compressors, ice diving equipment, generators, food, fuel, and so on. I had to fly on nine flights from Israel to the location of the shooting.

Then to live there in the middle of nowhere and to find the right bears and create the opportunity for Amos to get into the water and have a peaceful encounter with these magnificent animals… it is all very complicated.

We could not have done it without ADAM RAVETCH – who is not only the best Arctic Cinematographer in the world (and not only in my opinion), but also has 25 years of experience working with the Inuit people in the high Arctic.

Of course we could not have done it without the Kaludjack family. Two members of the family, Billy and Patrick Kaludjak, who were with us on the shoot, died a year and a half later when their snowmobile broke through the ice.

Our film is dedicated to the memory of these two wonderful human beings, who we had the privilege to know even if it was for a short period of time.

The other difficulty was to get our protagonist open up and talk about things that he kept inside for 40 years. It is always a complicated issue to get someone’s trust; it’s more complicated when it’s on film and it’s even more complicated when your protagonist is one of the best and most famous in his field.

JP&N: How long did it take to film?

Nir: It took us 10 years to get this movie off the ground. It was also how Yonatan and I have met, and started to work on this and DOLPHIN BOY (another of their films). The main reason it took us so long was that we had to raise a feature film budget for a documentary; and we were deferring to go with Amos all the way to the arctic and try to take his picture.

JP&N: Please share some anecdotes/incidents in the making of the Picture of His Life.

Menkin: One day, we left Adam and Billy Kauldjack RIP on a small island, maybe 50 meters by 10 meters with a camera and a drone.

We wanted to get a shot of Amos alone in the water in the empty Arctic sea… we never used that shot in the film BTW (by the way).

We sailed away from them (to allow) Adam to fly the drone back and forth above Amos with no boats in the frame. The time passed, strong winds, maybe 20 minutes (later).

When Adam reported to us that he got the shot, we sailed back to Amos to take him out of the water. He was very cold, so we warmed him up with some hot water and tea when suddenly I hear screaming from the little island.

I looked back terrified. I thought a bear got on the island or something like that, and to my amazement there was no island, literally.

The tide came in very fast and almost drowned Adam and Billy with our expensive gear. We sailed as fast as we could to get them out of there in the very last second.

JP&N: How long have you two been working together?

Nir: After (his first film) 39 POUNDS OF LOVE, I met Yonatan when I was approached by a producer to direct the film about Amos. We joined forces on DOLPHIN BOY and now PICTURE OF HIS LIFE while we both have our own films. Yonatan focuses on documentaries, like MY HERO BROTHER, and I’m writing and directing fiction and docs. We are good friends and both like road trip movies and wanted to give this story all the elements we have in our previous work.

JP&N: What has been the response in Israel to the film?

Menkin: The response is unbelievable. We are in cinemas all over the country, and sold out almost every screening. The story of Amos with the Yom Kippur war is the story of a whole generation.

People love adventures and inspiring human beings who chase their dreams and are fighting their own fears, doubts and inner demons. To my happiness, people in Israel are starting to care about the future of our planet more and more, and our film is also about that. There is something to relate to in our film for everyone.

The most touching feedback to the film was from my eight year old daughter who said, “Abba I liked the film very much. I just didn’t like it when Amos father was yelling at him and I didn’t understand why did you have to include wars in your film?”

I didn’t know how to answer that.

JP&N: Anything else you’d like to add?

Nir: We just premiered PICTURE OF HIS LIFE in North America, and got incredible reviews and standing ovations. We are excited to tour with it around the world (in Canada as well) and spread the message.

Features

Why casinos reject card payments: common reasons

Online casino withdrawals seem simple, yet many players experience unanticipated decreases. Canada has more credit and debit card payout refusals than expected. Delays or rejections are rarely random. Casino rules and technical processes are rigorous. Identity verification, banking regulations, bonus terms, and technological issues might cause issues.

Card payment difficulties can result from insufficient identification verification. Canadian casinos must verify players’ identities before accepting card withdrawals. If documentation are missing, obsolete, or confusing, the request may be stopped or denied until verified.

Banks and card issuers’ gaming policies are another aspect. Some Canadian banks limit or treat online casino payments differently from card refunds. In such circumstances, the casino may recommend a more reliable withdrawal method.

For Canadian players looking to compare bonus terms and payout conditions, check https://casinosanalyzer.ca/free-spins-no-deposit/free-chips. This article explores the main reasons Canadian casinos reject card payouts, from KYC hurdles to bank-specific restrictions, so you know exactly what to watch for.

Verification Issues: Why Identity Checks Matter

KYC rules must be activated by licensed casinos. Players need to submit proof of their identity, address and age. If any documentation is missing, expired or unclear, the withdrawal will be denied. In Canada, for instance, authorities like the AGCO or iGaming Ontario have been cracking down on KYCs by demanding that submitted documents – whether photo ID, utility bills or bank statements – be consistent with all account details.

Common errors are submitting screenshots, cropped photos or documents with names, dates or addresses that aren’t entirely visible. Just the slightest differences in spelling or abbreviations or formatting can get these blocks triggered.

Another possibility is that the account was red flagged if previous withdrawals were already made without partial verification. Keeping precise, readable documents helps facilitate approvals and cuts through delays and frustrating red tape, as Canadian gamblers access their winnings both safely and quickly.

Timing Matters

Verification isn’t always instant. Documents being submitted during the busiest times, or on weekends or holidays can only prolong that approval process, and the withdrawal sitting pre-approved – or refused for that matter – until the casino reviews the paperwork. A lot of players feel disappointment not due to mistakes, but only for that a verification team still hasn’t checked their documents! This can be especially frustrating when winnings come from free chips or bonus play and players are eager to cash out.

Keep personal information current and only submit clear legible files to reduce the processing time. Ensure that any scans or photos are sharp, fully visible and there is no detail missing. Preventing Gaffes With submission guidelines to read over ahead of time and directions for following them exactly, verification issues can often be significantly minimized, avoiding delay in accessing winnings and making the lie down withdrawal process that much smoother at Canadian online casinos.

Banking Restrictions and Card Policies

Not all credit or debit cards are eligible for casino withdrawals. Many Canadian banks restrict transactions related to gambling. For example, prepaid cards, virtual cards, or certain credit cards may allow deposits but block withdrawals. Even if deposits work, a payout can fail if the bank refuses incoming gambling credits.

Cards issued outside Canada can also be declined due to international processing rules. Currency conversion restrictions may prevent a CAD payout to a USD card, depending on the bank’s policies.

Banks keep an eye on abnormal or frequent transactions. Online casinos can flag large or multiple withdrawals as suspicious and in such cases may impose temporary blocks on withdrawals or outright decline the withdrawal until the issuing bank confirms them with its account holder. Contacting your bank in advance will avoid any surprises and make withdrawals go more smoothly. What to consider when using your card in Canada:

- Check if your card type supports gambling withdrawals (prepaid, virtual, and some credit cards may not).

- Confirm whether your bank allows international online casino payouts.

- Be aware of currency conversion restrictions.

- Monitor withdrawal frequency to avoid triggering fraud alerts.

- Contact your bank ahead of time to authorize or clarify online gambling transactions.

- Keep alternative withdrawal methods ready, such as e-wallets or bank transfers.

Being aware of these constraints prevents Canadian players from having declined payouts, delays and waste of time when it comes to handling the casino money properly.

Wagering Requirements and Bonus Conditions

Many Canadians chase casino bonuses, including deals built around free chips, but these offers always come with conditions, Wagering requirements usually require players to bet a multiple of the bonus before withdrawing. Attempting a payout before meeting these conditions will be automatically declined. Not all games contribute equally: slots often count 100%, table games 10–20%, and certain features nothing at all.

Misinterpretation of this, can make it appear as though a withdraw should be valid, while the casino believes there are unmet bonus requirements. Some casinos also impose a minimum withdrawal amount and will cap card payouts. And if you have more than the minimum in your account, a limit set off by your bonus could limit withdrawal. By testing these issues early on, you can save yourself a lot of aggravation. How to manage bonus conditions effectively:

- Have a close look at the terms of the bonus – check out wagering requirements, game contribution and time limits.

- Track your progress – note how much of the bonus has been wagered and which games contribute most.

- Plan your gameplay – prioritize slots or eligible games to efficiently meet wagering.

- Check withdrawal limits – ensure your balance meets minimums and bonus-specific caps.

- Avoid early withdrawals – never attempt a cash-out before meeting all conditions.

- Use trusted sources – platforms like CA CasinosAnalyzer can clarify real requirements and prevent surprises.

Following these steps helps players meet bonus conditions without stress and makes bankroll management smoother.

Features

What is the return on investment of US military spending on Israel?

By GREGORY MASON A recurring theme of Israel’s critics is that were it not for US spending on its war machine, it would be unable to wage genocide. I will leave the genocide issue (sic, I mean non-issue) aside as it has been well covered here and here.

Of course, right now (March 11), the war is going well for Israel and the US. In fact, the Israeli and American air forces are showing a level of coordination enabled by decades of close cooperation between the two militaries. I recall a conversation with an IDF colonel, the commander of a base near Eilat, in 2010, during a mission that gave participants access to high-level military briefings. Tensions between Israel and the US had soured, as they periodically do, and I asked whether this ebb and flow in political posturing affected military operations. The colonel said political leaders come and go, but the cooperation between the Israeli and American militaries is very tight. To quote him, “they need us as much as we need them. We are their eyes and ears in this part of the world.”

Many on both the right and left call for the US to disengage from Israel, especially with respect to defence spending. First, let us look at facts.

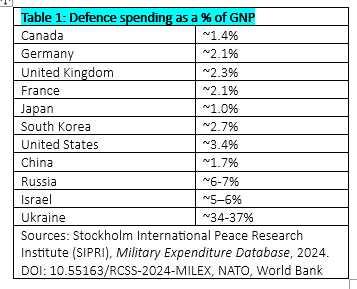

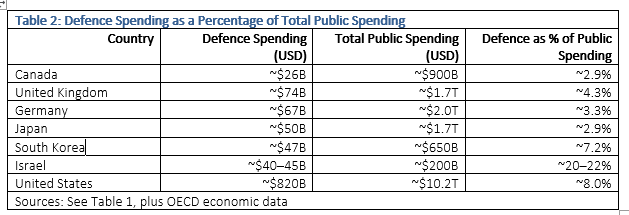

Table 1 readily shows the impact of the war in Ukraine, with Russia’s spending also reflecting wartime demands. Israel’s total commitment of 5-6% of GDP amounts to $45 billion in defence spending, reflecting its perpetual need to defend itself and maintain a permanent reserve force. Table 2 elaborates on defence spending as a share of public spending. Unlike other countries that have been free riding under the US military umbrella (and Canada is the most egregious of the lot), Israel has made very substantial commitments to its own defence. The $3.8 billion spent on hardware for US equipment is a fraction of Israel’s total defence budget of about $43 Billion. All U.S. financial aid to any country for military hardware must be spent on U.S.-manufactured equipment by law.

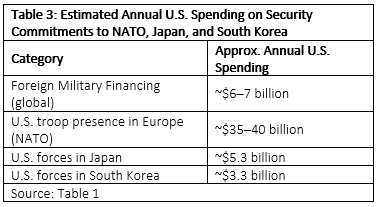

Critics of US defence funding for Israel miss two key points. First, as Table 3 shows, financing sent to Israel does not involve troop deployment. Israel does not want the US to station troops within its borders. The costs of maintaining troop deployments and all the associated support costs for NATO, Japan, and South Korea are orders of magnitude higher than the financing for the hardware it provides to Israel.

Second, and the current joint US/Israeli operations in Iran bear this out, Israel has dramatically improved the equipment platforms it purchased. Examples include:

- The F-15 has benefited from Israeli wartime use, resulting in major improvements, including a redesigned cockpit layout, increased range through fuel redesign, improved avionics, new weaponry, helmet-mounted targeting, and structural strengthening.

- Because Israel was an early partner in the fighter’s development and had access to its top-secret software suite, the Israeli version of the F-35 is a radically different plane than the model delivered. Improvements include increasing operational range, embedding advanced air defence detection, and integrating the fighter with Israel’s defence network, creating extensive system integration. This proved instrumental in the rapid establishment of air superiority in the 12-day war in 2025.

- The THAAD (Terminal High Altitude Area Defence) program has benefited from a joint research and development relationship between Israel and the U.S.

- Finally, Iron Dome has contributed to U.S. air defence development, particularly the Tamir interceptor technology, battle management, target discrimination, and the development of a layered air defence system.

No senior military or political official questions the return on investment American gains by funding Israel’s acquisition of U.S. military hardware.

Features

Why Returning Players Often Stick to a Few Favorite Games on Platforms Like Gransino Casino

Many online casino players develop clear preferences over time, and Gransino Casino highlights how familiar games often become the center of regular play sessions.

Online casinos typically offer large catalogs filled with hundreds of different slot titles. While this variety allows players to explore new experiences, many returning users gradually settle on a smaller group of games that they revisit regularly. This pattern appears across many digital gaming environments, where familiarity often becomes just as important as novelty.

Platforms such as Gransino Casino demonstrate how this behavior emerges in practice. Even though players have access to many different titles, returning visitors frequently gravitate toward games they already know and understand.

Familiar mechanics reduce learning time

One reason players return to the same games is that they already understand how those titles work. Each slot game has its own rules, bonus features, and payout structure. When a player first opens a new title, they often need a few minutes to understand the paytable, special symbols, and feature triggers.

Once that learning process has taken place, the game becomes easier to approach in future sessions. Players do not need to spend time reviewing instructions or exploring unfamiliar mechanics. Instead, they can begin playing immediately with a clear sense of how the game operates.

On platforms like Gransino Casino, this familiarity can make certain titles stand out as reliable choices. When players know what to expect from a game, the experience often feels smoother and more predictable during short play sessions.

Personal preferences shape long-term choices

Another factor influencing player behavior is personal preference. Some players enjoy specific visual themes such as mythology, adventure, or classic fruit machine designs. Others may prefer particular gameplay features, such as free spins, cascading reels, or bonus rounds.

Over time, players tend to identify the games that best match these preferences. Once they find titles that align with their interests, they are more likely to return to those games rather than start the search process again.

This pattern can be seen on Gransino Casino, where players browsing the lobby may explore different titles at first but eventually settle on a smaller group of favorites that suit their individual style.

Habit formation in digital gaming

Habit formation also plays a role in why players repeatedly choose the same games. In many digital environments, users develop routines that guide how they interact with a platform. This behavior is visible across streaming services, mobile games, and online casinos.

Once a player has established a routine, returning to familiar content often becomes part of that pattern. For example, a player might log in and immediately open the same slot they played during previous sessions. The familiarity of the interface, symbols, and features can make the experience feel more comfortable.

Platforms like Gransino Casino support this behavior by maintaining consistent game availability and allowing players to locate previously played titles easily within the lobby.

Exploration still remains part of the experience

Although many players develop favorite games, exploration remains an important part of the online casino experience. New titles continue to appear on casino platforms, introducing different mechanics, themes, and visual styles.

Players often alternate between their familiar choices and occasional experimentation with new games. A player might return to a favorite slot for most sessions while occasionally trying recently released titles to see if they offer something interesting.

The wide selection available on Gransino Casino allows this balance between familiarity and discovery. Players can continue returning to the games they enjoy while still having the option to explore new additions within the platform’s catalog.

Ultimately, the tendency to revisit favorite games reflects how players build their own routines within digital entertainment environments. Familiar titles offer a comfortable starting point, while new releases provide opportunities for occasional exploration, creating a mix of consistency and variety within each player’s experience.