RSS

A murder victim was anonymous for 13 years. Jewish genealogists found her name.

(JTA) — On March 29, 2011, the body of a decapitated woman was discovered in a vineyard in Arvin, a town just over the Los Angeles county line.

Earlier this month, nearly 13 years later, the victim was identified as Ada Beth Kaplan, a Jewish woman who was 64 at the time of her death.

The tortuous journey to cracking the mystery of Kaplan’s name involved a “long and hard” multiyear effort by a DNA-focused nonprofit, eight generations of family records and the work of two Jewish genealogists who understood just how thorny it can be, sometimes, to ascertain the identity of an unknown Ashkenazi Jew.

“It’s kind of a miracle that this was figured out, in a lot of ways,” said Adina Newman, the co-founder of the DNA Reunion Project at the Center for Jewish History in New York City. “Giving Ada Kaplan her name back when people didn’t even realize she was missing is just such a big deal to me.”

Kaplan’s decomposing body was found naked, decapitated and mutilated in 2011, with few clues to who she was or how she met her end. Her case remained unsolved and, in 2020, the Kern County Coroner enlisted the help of the DNA Doe Project, an organization that uses genetic genealogy analysis to build out the family tree of unidentified victims in an effort to find their identities.

Kaplan’s DNA indicated that she was an Ashkenazi Jew, an ethnic heritage that was as much a challenge as a step forward. The team of researchers initially found only Kaplan’s distant cousins, who had common Eastern European Jewish last names and spanned eight generations.

That made it difficult to pinpoint her specific ancestors, among all people with those surnames, and place them in a family tree. Researchers were barred from using certain large DNA databases such as Ancestry.com and 23andMe, whose terms of service bar working with police.

“Honestly it scared me, because I didn’t know that I could solve her case,” Missy Koski, the researchers’ team leader, told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency regarding Kaplan’s Ashkenazi heritage.

Koski recalled the recent case of a John Doe who was one quarter Ashkenazi Jewish, which went unsolved for a long time because of difficulties the team encountered in identifying his Jewish great-grandparents. That case was ultimately solved through the non-Jewish side of his family tree.

“We worked very hard on that for a long time, so I already knew how difficult it could be in terms of trying to piece those family members together,” Koski explained.

To further complicate matters, researchers eventually discovered that three of Kaplan’s four grandparents were immigrants — meaning they had to search Eastern European records to connect them to each other.

Many Ashkenazi families have changed their surnames or spelled the same names differently. And Ashkenazi Jews are a historically endogamous group. They are descended from a limited population and procreate from within that small tribe for generations. That means an Ashkenazi Jew may have a strong DNA match to someone they’re not actually closely related to.

For help, the team turned to an expert in Jewish genealogy: Susan King, the founder of JewishGen, an online database for Jewish genealogy research. King’s extensive knowledge of Jewish genealogy led the DNA Doe team to Kaplan’s great-grandparents, including an ancestor born in Lithuania in the 1780s. But King died in Dec. 2022 before Kaplan was identified on the family tree.

The DNA Doe Project then approached Newman, whose DNA Reunion Project helps connect Holocaust survivors with their long-lost relatives. Newman had previously volunteered on another John Doe case involving a person of Ashkenazi heritage whose body was found in Maine in 2000. That John Doe was was ultimately identified by the local medical examiner and the FBI as Philip Kahn, a cab driver from Las Vegas, who had appeared as an extra in the 1988 film “Rain Man” with his wife Jean.

“My other work is in… helping survivors find families and reconnecting,” she said. “So it’s kind of the same ballpark, in a way, and I have the skill set. I would like to use it for the biggest mitzvahs possible, is the way I see it.”

DNA testing has recently come under scrutiny in the Jewish world due to privacy concerns that arose when hackers stole the data of Ashkenazi users of 23AndMe in a targeted attack, and put the information up for sale. The genetic testing company is now facing a class action lawsuit in federal court for negligence, invasion of privacy, unjust enrichment, and breach of implied contract.

But for genealogists like Koski and Newman, the benefits of these databases outweigh the risks. Newman said privacy problems extend far beyond the potential problems associated with DNA databases — and that to identify someone conclusively, researchers more than genetic records.

“People think that DNA does all these things, but people don’t realize the digital footprints they leave. We shed DNA every day of our lives,” Newman said. “So I think people catastrophize a lot of the DNA stuff when really… you may get matched to me, but I’m not finding you because the DNA told me something. I’m finding you because of your digital footprint. I’m finding you through public records, finding you through your Facebook profile.”

She added, “DNA is kind of the starting point.”

In July 2023, the team of researchers working on Kaplan’s case found two potential family members who agreed to provide DNA samples for comparison. One of her relatives lived in the heavily Jewish neighborhood of Forest Hills in Queens, New York City. That, in turn, finally led to Kaplan’s identity.

A cause or location of death has not been determined in Kaplan’s case, and the Kern County Sheriff detectives learned in interviews with family members that a missing person’s report was never filed on her. She is not known to have had any children. Likewise, no suspect has been identified in connection with her death.

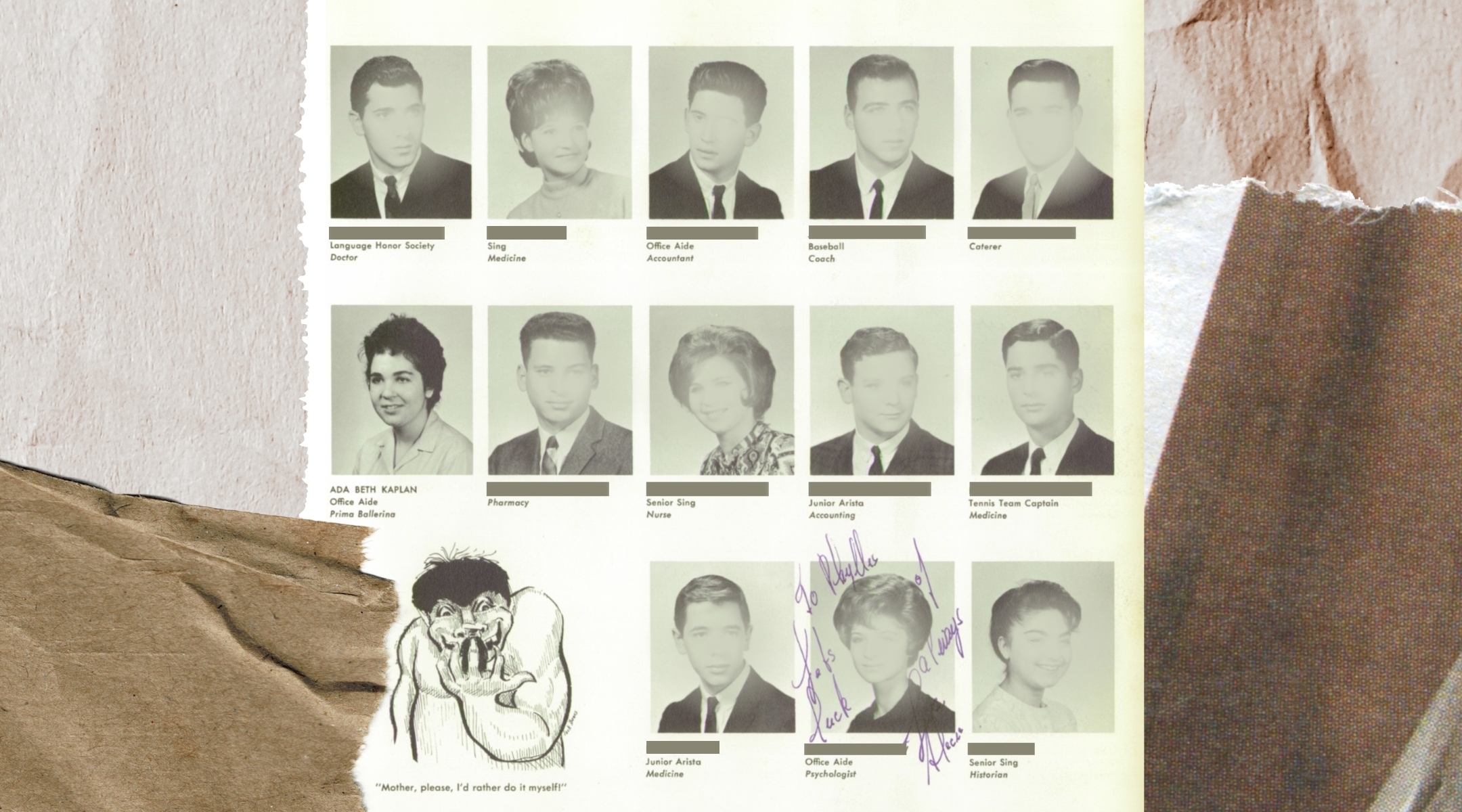

But researchers did learn of some details of her life: Online yearbook records show Kaplan attended Forest Hills High School, where, as a senior, she was an office aide and one of the recipients of the 1963 New York State Scholarship Award. She wrote that she had aspirations to be a prima ballerina.

—

The post A murder victim was anonymous for 13 years. Jewish genealogists found her name. appeared first on Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

RSS

After False Dawns, Gazans Hope Trump Will Force End to Two-Year-Old War

Palestinians walk past a residential building destroyed in previous Israeli strikes, after Hamas agreed to release hostages and accept some other terms in a US plan to end the war, in Nuseirat, central Gaza Strip October 4, 2025. Photo: REUTERS/Mahmoud Issa

Exhausted Palestinians in Gaza clung to hopes on Saturday that US President Donald Trump would keep up pressure on Israel to end a two-year-old war that has killed tens of thousands and displaced the entire population of more than two million.

Hamas’ declaration that it was ready to hand over hostages and accept some terms of Trump’s plan to end the conflict while calling for more talks on several key issues was greeted with relief in the enclave, where most homes are now in ruins.

“It’s happy news, it saves those who are still alive,” said 32-year-old Saoud Qarneyta, reacting to Hamas’ response and Trump’s intervention. “This is enough. Houses have been damaged, everything has been damaged, what is left? Nothing.”

GAZAN RESIDENT HOPES ‘WE WILL BE DONE WITH WARS’

Ismail Zayda, 40, a father of three, displaced from a suburb in northern Gaza City where Israel launched a full-scale ground operation last month, said: “We want President Trump to keep pushing for an end to the war, if this chance is lost, it means that Gaza City will be destroyed by Israel and we might not survive.

“Enough, two years of bombardment, death and starvation. Enough,” he told Reuters on a social media chat.

“God willing this will be the last war. We will hopefully be done with the wars,” said 59-year-old Ali Ahmad, speaking in one of the tented camps where most Palestinians now live.

“We urge all sides not to backtrack. Every day of delay costs lives in Gaza, it is not just time wasted, lives get wasted too,” said Tamer Al-Burai, a Gaza City businessman displaced with members of his family in central Gaza Strip.

After two previous ceasefires — one near the start of the war and another earlier this year — lasted only a few weeks, he said; “I am very optimistic this time, maybe Trump’s seeking to be remembered as a man of peace, will bring us real peace this time.”

RESIDENT WORRIES THAT NETANYAHU WILL ‘SABOTAGE’ DEAL

Some voiced hopes of returning to their homes, but the Israeli military issued a fresh warning to Gazans on Saturday to stay out of Gaza City, describing it as a “dangerous combat zone.”

Gazans have faced previous false dawns during the past two years, when Trump and others declared at several points during on-off negotiations between Hamas, Israel and Arab and US mediators that a deal was close, only for war to rage on.

“Will it happen? Can we trust Trump? Maybe we trust Trump, but will Netanyahu abide this time? He has always sabotaged everything and continued the war. I hope he ends it now,” said Aya, 31, who was displaced with her family to Deir Al-Balah in the central Gaza Strip.

She added: “Maybe there is a chance the war ends at October 7, two years after it began.”

RSS

Mass Rally in Rome on Fourth Day of Italy’s Pro-Palestinian Protests

A Pro-Palestinian demonstrator waves a Palestinian flag during a national protest for Gaza in Rome, Italy, October 4, 2025. Photo: REUTERS/Claudia Greco

Large crowds assembled in central Rome on Saturday for the fourth straight day of protests in Italy since Israel intercepted an international flotilla trying to deliver aid to Gaza, and detained its activists.

People holding banners and Palestinian flags, chanting “Free Palestine” and other slogans, filed past the Colosseum, taking part in a march that organizers hoped would attract at least 1 million people.

“I’m here with a lot of other friends because I think it is important for us all to mobilize individually,” Francesco Galtieri, a 65-year-old musician from Rome, said. “If we don’t all mobilize, then nothing will change.”

Since Israel started blocking the flotilla late on Wednesday, protests have sprung up across Europe and in other parts of the world, but in Italy they have been a daily occurrence, in multiple cities.

On Friday, unions called a general strike in support of the flotilla, with demonstrations across the country that attracted more than 2 million, according to organizers. The interior ministry estimated attendance at around 400,000.

Italy’s right-wing government has been critical of the protests, with Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni suggesting that people would skip work for Gaza just as an excuse for a longer weekend break.

On Saturday, Meloni blamed protesters for insulting graffiti that appeared on a statue of the late Pope John Paul II outside Rome’s main train station, where Pro-Palestinian groups have been holding a protest picket.

“They say they are taking to the streets for peace, but then they insult the memory of a man who was a true defender and builder of peace. A shameful act committed by people blinded by ideology,” she said in a statement.

Israel launched its Gaza offensive after Hamas terrorists staged a cross border attack on October 7, 2023, killing some 1,200 people and taking 251 people hostage.

RSS

Hamas Says It Agrees to Release All Israeli Hostages Under Trump Gaza Plan

Smoke rises during an Israeli military operation in Gaza City, as seen from the central Gaza Strip, October 2, 2025. Photo: REUTERS/Dawoud Abu Alkas

Hamas said on Friday it had agreed to release all Israeli hostages, alive or dead, under the terms of US President Donald Trump’s Gaza proposal, and signaled readiness to immediately enter mediated negotiations to discuss the details.