RSS

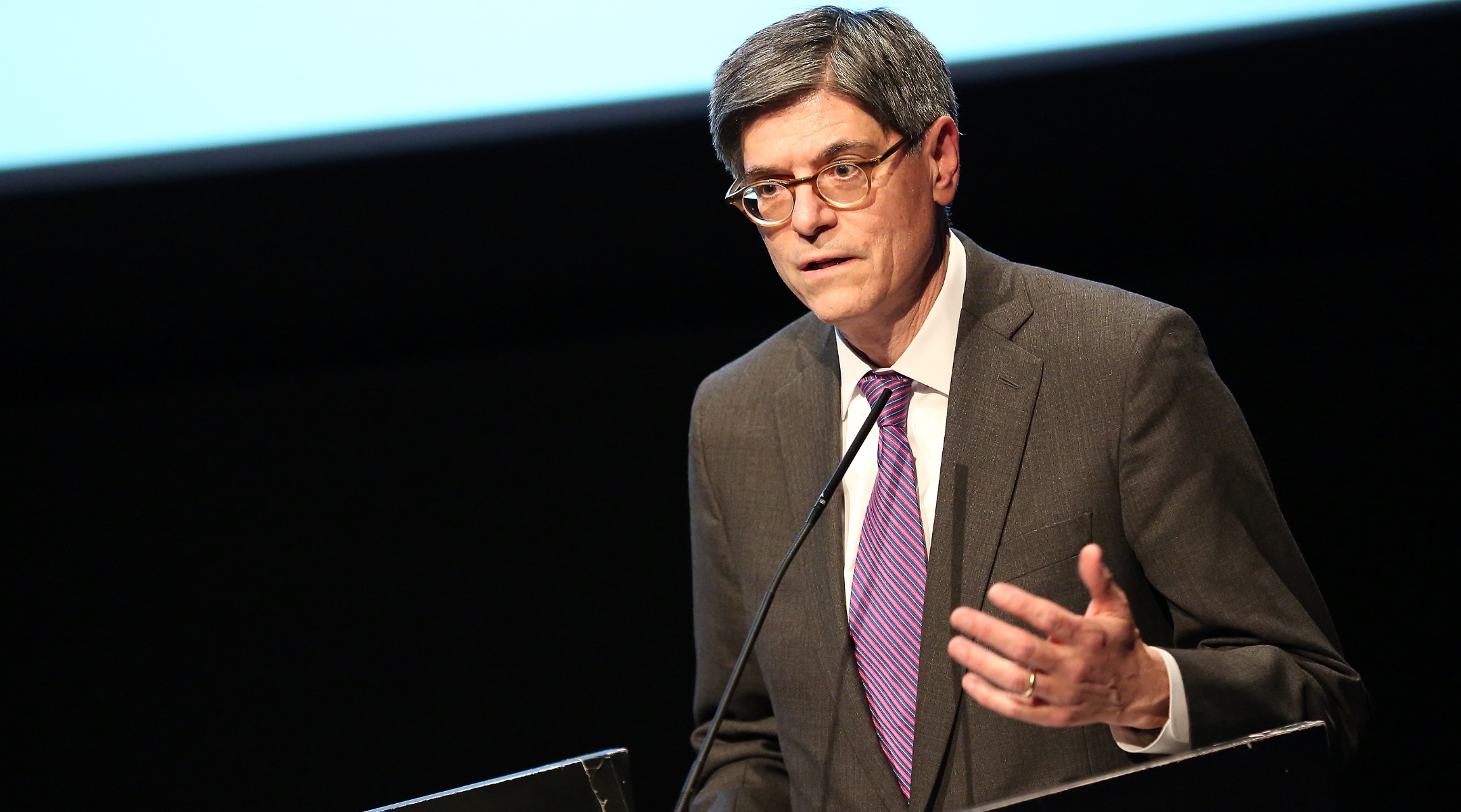

Jack Lew, Orthodox Jew who led US Treasury, is Biden’s pick for Israel ambassador

WASHINGTON (JTA) — Under President Barack Obama, Jack Lew gained praise for fulfilling both his duties as secretary of the treasury and his obligations as an Orthodox Jew.

Now, President Joe Biden is asking Lew to complete a challenge that could be even harder: helping establish diplomatic ties between Israel and Saudi Arabia as the next U.S. ambassador to Israel.

Lew, 68, will succeed Tom Nides, who left the post in July, the White House announced Monday morning.

Lew declined a Jewish Telegraphic Agency request for comment last week, as his name solidified among a pack of people in contention.

Lew’s appointment must be confirmed by the Senate, which is led by a Democratic majority. He would be the fourth Jewish man in a row to serve in the role, following Nides, David Friedman and Dan Shapiro.

Lew, who also served as Obama’s chief of staff before leading the Treasury Department, has drawn words of support from Jewish leaders in Washington who pointed to his experience in public office, his skills as a negotiator, his involvement in Jewish life and his close relationship with Jewish organizations.

“He’s a very thoughtful person, and has always been open and accessible,” said Nathan Diament, the Washington director of the Orthodox Union. “He has an encyclopedic knowledge of policy issues, starting with budgetary policy issues.”

As Lew’s anticipated nomination neared, he also drew criticism from right-wing activists. Morton Klein, president of the Zionist Organization of America, wrote in a Jerusalem Post op-ed that Lew’s appointment would be “deeply concerning” because of his involvement in what Klein calls “the Obama administration’s hostility to the Jewish state and the Jewish people.”

If he is confirmed, Lew will take up the post at a time of instability in Israel, which is contending with mass protests of the right-wing government’s actions to weaken the Supreme Court, in addition to a surge in Israeli-Palestinian violence.

Alongside those issues, the Biden administration is pursuing an agreement between Israel and Saudi Arabia that, if reached, would mark a major foreign policy breakthrough in the region. U.S.-brokered negotiations over a potential accord are reportedly underway.

Here’s what you need to know about Lew, his career so far and the challenges he could face in the ambassador role.

He’s a negotiator who could bring his skills to diplomacy.

Lew earned a reputation for resolving complex negotiations during his two stints as director of the Office of Management and Budget, under Obama as well as President Bill Clinton. The OMB director oversees funding for the vast federal bureaucracy and negotiates budgets with Congress.

As OMB director in the last two years of Clinton’s presidency, Lew negotiated a balanced budget with the same Republican leadership that was seeking Clinton’s ouster for the Monica Lewinsky scandal. The talks succeeded: Clinton left office with a budget surplus.

As ambassador to Israel, Lew could use that experience in making a Saudi-Israel deal happen. The treaty would follow the agreements Israel signed in 2020 with several Arab countries, known as the Abraham Accords — but it would also be more complex.

As described by Biden in July to New York Times columnist Tom Friedman, the deal would involve stemming Saudi Arabia’s growing trade ties with China; a pledge that the United States will guarantee Saudi Arabia’s security; and the establishment of a Saudi civilian nuclear program along with the sale of advanced weapons systems. The status of Palestinians is also shaping up to take increased prominence in the negotiations.

That’s a lot of moving parts, and the ambassador to Israel would be key to reassuring the United States’ closest ally in the region that a deal would not endanger Israel.

“He really knows the issues inside and out,” Diament said. “You’re not going to pull the wool over his eyes, which is generally a good thing. But it also means you can come in and make the right kinds of arguments based on the facts and based on the situation, hopefully, you have a chance at having him on your side.”

Lew is also devoted to his bosses and knows when to stand firm. As OMB director under Obama, before he became the president’s chief of staff, he stood firm on protecting entitlement programs — Obama’s top priority — during talks with Republicans in 2011. Lew was furious with Republicans for what he believed was their lack of respect for the president, and in turn, earned the scorn of Republicans who called him the man who “can’t get to yes.”

Biden, who grew close to Lew during Obama’s second term — when Biden was vice president and Lew was Treasury secretary — could expect the same loyalty.

He’s used to defending controversial stances to the Jewish community.

As Treasury secretary, Lew was tapped as Obama’s point man to explain — and defend — the Iran nuclear deal in the Jewish community. The deal, which curbed Iran’s nuclear program in exchange for sanctions relief, was bitterly opposed by Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. A range of large Jewish organizations, along with Republicans in Congress, advocated against it.

Lew had been involved in the issue for years. He oversaw the enforcement of sanctions that helped bring Iran to the negotiating table and used his knowledge of the deal’s particulars — as well as his intimate knowledge of the Jewish community — to pitch the deal to the American Israel Public Affairs Committee, or AIPAC, and others who were deeply skeptical.

He was booed that year at the annual Jerusalem Post conference in New York when he defended the deal. A year after leaving office, and a year before President Donald Trump scuppered the deal, Lew was still defending it to a Jewish audience.

“The idea that somehow the Iran deal was not in Israel’s interest is something I disagree with,” Lew said in 2017 at a conference at Columbia University’s Institute for Israel and Jewish Studies. “I think Israel is safer today than it was before the deal when Iran was genuinely approaching having a nuclear weapon.”

His continued defense of the agreement especially irks Klein’s ZOA, which accuses him of “shilling” for the deal. Lew “stuck to and trotted out every Obama administration line (and lie) to try to sell the Iran deal to the American-Jewish public,” Klein wrote in his op-ed.

William Daroff, the CEO of the Conference of Presidents of Major American Jewish Organizations, said Lew’s helpfulness to the Jewish community straddled multiple disciplines and that he “was always very attentive to the Jewish communal agenda.” He praised Lew for stanching funding to terrorists as treasury secretary, as well as for his efforts to aid Holocaust survivors or combat efforts to amend tax laws on charitable contributions.

Lew did not always see eye to eye with his Obama administration colleagues on Israel-related matters. In the administration’s final days in late 2016, Lew and Biden recommended vetoing a U.N. Security Council resolution condemning settlement building. In the end, the United States abstained, and the resolution went through.

At the 2017 Columbia University conference, Lew said he understood the rationale behind the decision not to veto. Obama administration officials, he said, used the abstention to leverage a less toxic resolution — but he still regretted it.

“Personally, I wish the resolution hadn’t been there at all. I’m not happy that there was a resolution,” he said. “I’m also happy it wasn’t in its original form where we would have had to veto it, but then the rest of the world would have been voting for this even harsher condemnation.”

He’s an Orthodox Jew who doesn’t place his observance at the center of his public identity.

Unlike Joe Lieberman, the Jewish former senator from Connecticut who was the Democrats’ vice presidential nominee in 2000, Lew has not placed his Orthodoxy front and center in his political identity.

But he has not been shy about it either, and in 2012, he stumped for Obama among Orthodox Jews and routinely briefed Orthodox Jewish groups about administration policies.

Obama, nominating Lew in 2013 to be Treasury secretary, said he was drawn to Lew in part because of his faith. “Maybe most importantly, as the son of a Polish immigrant, a man of deep and devout faith, Jack knows that every number on a page, every dollar we budget, every decision we make has to be an expression of who we wish to be as a nation, our values,” Obama said.

Stumping for Obama’s reelection in 2012, Lew told JTA that the president earned his loyalty in part by respecting his faith.

“As a father who is at home and has dinner with his girls, he values that Shabbat is my time being with my family,” Lew said then. “I could not ask for someone to be more respectful and supportive, and that’s the reason it works.”

Lew has deep connections to Israel, including as a board member of NLI USA, the American support group for the National Library of Israel.

He likes to advise young Orthodox Jews to consider public service, but he counsels humility. “You can practice your faith openly, but don’t ever take it for granted,” he said in 2019 at a New York forum with Lieberman. “And keep in mind that accommodations are being made for you.”

Lew was not the only candidate for the ambassador post with deep involvement in his Jewish community. Other names floated include Ted Deutch, the American Jewish Committee CEO who retired last year as a Florida Democrat in the U.S. House of Representatives, and Robert Wexler, the former Florida Democratic congressman who now leads the Center for Middle East Peace and who was a close contender with Nides for the post in 2021.

Also touted was Kathy Manning, the Democratic congresswoman from North Carolina who is a past president of the Jewish Federations of North America. She would have been the first woman ever to hold the post.

A favorite story about Lew’s Judaism involves his walk home from synagogue on Shabbat when he was Clinton’s OMB director, hearing the phone ring and letting it click through to the answering machine — only to hear a staffer for Clinton, who was in another time zone, relay the president’s apology. After an earlier call, Clinton realized he was disturbing Lew’s Sabbath and wanted to say sorry.

Lew has a mild-mannered sense of humor. When he was attending Beth Sholom, an Orthodox synagogue in Potomac, Maryland, a rabbi jokingly asked him to run for treasurer. Lew rejoined that running the OMB was challenging enough.

And in discussions of Israel, he has displayed diplomatic skills of a sort. In a debate with Tevi Troy, a former senior Bush administration official who is also Orthodox, at a Beachwood, Ohio, Orthodox synagogue during the 2012 campaign, someone asked both men which their candidate would prefer — shawarma or falafel. Troy said Mitt Romney would opt for shawarma. Lew said Obama would happily eat either.

—

The post Jack Lew, Orthodox Jew who led US Treasury, is Biden’s pick for Israel ambassador appeared first on Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

RSS

After False Dawns, Gazans Hope Trump Will Force End to Two-Year-Old War

Palestinians walk past a residential building destroyed in previous Israeli strikes, after Hamas agreed to release hostages and accept some other terms in a US plan to end the war, in Nuseirat, central Gaza Strip October 4, 2025. Photo: REUTERS/Mahmoud Issa

Exhausted Palestinians in Gaza clung to hopes on Saturday that US President Donald Trump would keep up pressure on Israel to end a two-year-old war that has killed tens of thousands and displaced the entire population of more than two million.

Hamas’ declaration that it was ready to hand over hostages and accept some terms of Trump’s plan to end the conflict while calling for more talks on several key issues was greeted with relief in the enclave, where most homes are now in ruins.

“It’s happy news, it saves those who are still alive,” said 32-year-old Saoud Qarneyta, reacting to Hamas’ response and Trump’s intervention. “This is enough. Houses have been damaged, everything has been damaged, what is left? Nothing.”

GAZAN RESIDENT HOPES ‘WE WILL BE DONE WITH WARS’

Ismail Zayda, 40, a father of three, displaced from a suburb in northern Gaza City where Israel launched a full-scale ground operation last month, said: “We want President Trump to keep pushing for an end to the war, if this chance is lost, it means that Gaza City will be destroyed by Israel and we might not survive.

“Enough, two years of bombardment, death and starvation. Enough,” he told Reuters on a social media chat.

“God willing this will be the last war. We will hopefully be done with the wars,” said 59-year-old Ali Ahmad, speaking in one of the tented camps where most Palestinians now live.

“We urge all sides not to backtrack. Every day of delay costs lives in Gaza, it is not just time wasted, lives get wasted too,” said Tamer Al-Burai, a Gaza City businessman displaced with members of his family in central Gaza Strip.

After two previous ceasefires — one near the start of the war and another earlier this year — lasted only a few weeks, he said; “I am very optimistic this time, maybe Trump’s seeking to be remembered as a man of peace, will bring us real peace this time.”

RESIDENT WORRIES THAT NETANYAHU WILL ‘SABOTAGE’ DEAL

Some voiced hopes of returning to their homes, but the Israeli military issued a fresh warning to Gazans on Saturday to stay out of Gaza City, describing it as a “dangerous combat zone.”

Gazans have faced previous false dawns during the past two years, when Trump and others declared at several points during on-off negotiations between Hamas, Israel and Arab and US mediators that a deal was close, only for war to rage on.

“Will it happen? Can we trust Trump? Maybe we trust Trump, but will Netanyahu abide this time? He has always sabotaged everything and continued the war. I hope he ends it now,” said Aya, 31, who was displaced with her family to Deir Al-Balah in the central Gaza Strip.

She added: “Maybe there is a chance the war ends at October 7, two years after it began.”

RSS

Mass Rally in Rome on Fourth Day of Italy’s Pro-Palestinian Protests

A Pro-Palestinian demonstrator waves a Palestinian flag during a national protest for Gaza in Rome, Italy, October 4, 2025. Photo: REUTERS/Claudia Greco

Large crowds assembled in central Rome on Saturday for the fourth straight day of protests in Italy since Israel intercepted an international flotilla trying to deliver aid to Gaza, and detained its activists.

People holding banners and Palestinian flags, chanting “Free Palestine” and other slogans, filed past the Colosseum, taking part in a march that organizers hoped would attract at least 1 million people.

“I’m here with a lot of other friends because I think it is important for us all to mobilize individually,” Francesco Galtieri, a 65-year-old musician from Rome, said. “If we don’t all mobilize, then nothing will change.”

Since Israel started blocking the flotilla late on Wednesday, protests have sprung up across Europe and in other parts of the world, but in Italy they have been a daily occurrence, in multiple cities.

On Friday, unions called a general strike in support of the flotilla, with demonstrations across the country that attracted more than 2 million, according to organizers. The interior ministry estimated attendance at around 400,000.

Italy’s right-wing government has been critical of the protests, with Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni suggesting that people would skip work for Gaza just as an excuse for a longer weekend break.

On Saturday, Meloni blamed protesters for insulting graffiti that appeared on a statue of the late Pope John Paul II outside Rome’s main train station, where Pro-Palestinian groups have been holding a protest picket.

“They say they are taking to the streets for peace, but then they insult the memory of a man who was a true defender and builder of peace. A shameful act committed by people blinded by ideology,” she said in a statement.

Israel launched its Gaza offensive after Hamas terrorists staged a cross border attack on October 7, 2023, killing some 1,200 people and taking 251 people hostage.

RSS

Hamas Says It Agrees to Release All Israeli Hostages Under Trump Gaza Plan

Smoke rises during an Israeli military operation in Gaza City, as seen from the central Gaza Strip, October 2, 2025. Photo: REUTERS/Dawoud Abu Alkas

Hamas said on Friday it had agreed to release all Israeli hostages, alive or dead, under the terms of US President Donald Trump’s Gaza proposal, and signaled readiness to immediately enter mediated negotiations to discuss the details.