Uncategorized

A Jewish-American exile behind the Iron Curtain, he never lost his love for East Germany

Three thousand miles from his New York City home, as the August dawn broke over the Austrian landscape, 24-year-old Army draftee Stephen Wechsler took off his shoes, waded into the Danube River, and began to swim. He struggled at first, then realized the current was carrying him toward his destination: the Soviet zone of occupied Austria.

Wechsler’s act of betrayal took place in 1952. The U.S. Army had discovered that the young Jewish private first class had lied on his induction papers, denying that he had ever belonged to the Communist Party or any affiliated organizations. In truth, he had belonged to several Communist groups, starting at age 14.

When a letter arrived ordering him to appear before a military judge in Nuremberg, it didn’t specify the charge. It didn’t need to. Wechsler understood immediately. And in his mind, there was only one path left: flee the American zone and seek refuge behind the Iron Curtain.

What followed is one of the more improbable personal odysseys of the Cold War. Starting a new life in Communist East Germany, Wechsler remade himself as Victor Grossman — establishing himself as a columnist, interpreter for visiting American leftists like Jane Fonda, defender of his adopted homeland, crusader against fascism, and sharp critic of American capitalism.

In his final years, Victor/Stephen wrote an online newsletter called Berlin Bulletin, warning about the threat to German democracy posed by the far-right Alternative for Germany, and to American democracy posed by Donald Trump.

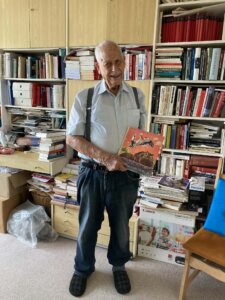

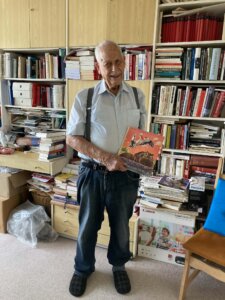

Victor/Stephen died last week in Berlin at age 97, bringing to a close a 73-year exile.

I came to know him through a cousin of his in Portland, Oregon, where I live. I interviewed him by phone last year, reaching him at his apartment on Karl Marx Allee, in the formerly Communist half of Berlin. He had just turned 96. I call him Victor/Stephen because he was known as the former in Germany and the latter among his friends and relatives in the U.S.

Victor/Stephen’s story is as much about love as it is about betrayal — perhaps more so. It was love for Renate, the East German woman he married soon after his desertion, that anchored him.

“I was homesick. But I was very much in love, and that made up for it,” he told me about Renate, who died some years ago.

He sometimes wondered whether he was like Don Quixote, jousting with windmills. But his ideals were so deeply rooted that he fought for them until his final years, writing his Berlin Bulletin with the same passion he had carried since adolescence.

From his teen years through Harvard and in factory jobs after graduation, Stephen Wechsler had been deeply involved in Communist causes. In the infamous 1949 riot that disrupted a Paul Robeson concert in Peekskill, N.Y., young Wechsler was among the leftists on buses attacked by stone-throwing white mobs while police stood by and did nothing.

His activism was interrupted by the Korean War, when he was drafted into the Army. He was relieved to be sent to West Germany rather than to the front lines. But his radical past caught up with him. Facing a possible five-year sentence in a military prison for lying on his induction papers, he decided to desert.

After his swim across the Danube, Wechsler didn’t know what to expect from Austria’s Soviet occupiers. Would they suspect he was a spy? He soon found himself in Bautzen, East Germany, where the Soviets had established a kind of halfway house for Western deserters. He found work in a factory, joined the German-Soviet Friendship Society, and so impressed his hosts that they appointed him culture director of a clubhouse for foreign deserters — organizing dances, ping-pong tournaments, chess matches, billiards, and other diversions from the temptations of Bautzen’s bars.

He fell in love with Renate, enrolled in the journalism program at Karl Marx University in Leipzig, married her, and after graduation went to work for an East Berlin publishing company, as he later wrote in his autobiography Crossing the River: A Memoir of the American Left, the Cold War, and Life in East Germany. He and Renate started a family, raising two sons.

Victor/Stephen caught the attention of John Peet, a British expatriate who published the German Democratic Report, an English-language newsletter sent abroad from East Berlin to counter negative portrayals of the German Democratic Republic. He worked for Peet for four years, helping publish reports that embarrassed West Germany by using Nazi-era documents to reveal how deeply the Federal Republic’s judiciary and bureaucracy were staffed by former officials of the Third Reich

He next worked for East Germany’s state radio network. A unique opportunity arose when East Germany’s Academy of Arts asked him to create an archive dedicated to Paul Robeson. Freelance work followed: articles on U.S. affairs for fellow Karl Marx University graduates now in senior media positions, dubbing dialogue for East German films, writing English subtitles.

He began writing his own books, including a history of the United States that emphasized the roles of women, Black Americans, peace movements and unions — themes that aligned with the ideals of Communist East Germany, at least partly because of their propaganda value against the West.

The opening of the Berlin Wall tossed him into a predicament. While he welcomed the end of travel restrictions on East Germans, he feared it would lead to the demise of East Germany as an autonomous state. Of course, he was right.

When West Germany formally merged with East Germany on Oct. 3, 1990, it was a stab in the heart for him. His wish was not to see “little GDR,” as he called it, swallowed by the capitalist West, but to take a middle path — allowing political freedom to bloom while preserving socialism and what he saw as the virtues of the East German state.

“I had always made clear that I was against the boils and carbuncles,” he wrote of the GDR’s abuses, “but wanted to cure, not kill the patient.”

When I interviewed him last year, he spoke wistfully about the GDR: child care, university education, dental care, eyeglasses, and hospital stays were free; rents were cheap; there was virtually no joblessness, he said; crime was practically nonexistent. While East Germans couldn’t travel to the West, they enjoyed inexpensive vacations in Prague, Budapest, and other Eastern Bloc cities.

“Life was not what people in the West imagined,” he told me.

In his recent writings and interviews, Victor/Stephen argued that the East German state took better care of its citizens than the U.S. does of its own. In a 2019 interview with the socialist magazine Jacobin, he said, “I shine a light on issues that Americans face: evictions, homelessness, mass incarceration, food banks, and the lack of access to food, healthcare, education, maternity leave, and childcare. I draw on some truly ghastly yet upsettingly commonplace examples.”

Although Victor/Stephen could sound like an ideologue, from my phone and email communications with him I got the distinct impression that love was a factor in his decision not to move back to the States. It was love not just for Renate, but also for East Germany, for its people, and for a dream he pursued until his final days: of trying to improve the lot of all humankind.

In our times, with authoritarianism on the rise around the world, with human rights and social justice slipping away, who is to fault Victor/Stephen for never abandoning such a dream?

The post A Jewish-American exile behind the Iron Curtain, he never lost his love for East Germany appeared first on The Forward.

Uncategorized

Netanyahu: ‘Our Forces Are Striking the Heart of Tehran With Increasing Strength’

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu participates in the state memorial ceremony for the fallen of the Iron Swords War on Mount Herzl, in Jerusalem, Oct. 16, 2025. Photo: Alex Kolomoisky/Pool via REUTERS

i24 News – Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu stated that Israeli forces had “eliminated the dictator Ali Khamenei” along with dozens of senior officials of Iran’s regime during a statement delivered from the roof of the Kirya, Israel’s defense headquarters.

“Yesterday, we eliminated the dictator Khamenei. Along with him, dozens of senior officials from the oppressive regime were eliminated,” Netanyahu said after a meeting with the Minister of Defense, the Chief of Staff, and the Director of Mossad. He added that he had issued instructions to continue the offensive.

According to Netanyahu, Israeli forces are “now striking at the heart of Tehran with increasing intensity,” a campaign he said will “increase further in the days to come.”

The Prime Minister also acknowledged the toll of the conflict on Israel, calling recent days “painful” and offering condolences to the families of victims in Tel Aviv and Beit Shemesh, while wishing a speedy recovery to those injured.

Netanyahu emphasized that the operation mobilizes “the full power of the Israel Defense Forces, like never before,” in order to “guarantee our existence and our future.” He also highlighted US support, noting “the assistance of my friend, the President of the United States, Donald Trump, and of the American military.”

“This combination of forces allows us to do what I have hoped to accomplish for 40 years: strike the terrorist regime right in the face,” Netanyahu concluded. “I promised it — and we will keep our word.”

Uncategorized

Trump Says Iran Military Operations Are ‘Ahead of Schedule,’ CNBC Reports

U.S. President Donald Trump speaks with White House Chief of Staff Susie Wiles and Secretary of State Marco Rubio during military operations in Iran, at Trump’s Mar-a-Lago resort in Palm Beach, Florida, U.S. February 28, 2026. The White House/Social Media/Handout via REUTERS

US President Donald Trump told CNBC on Sunday that US military operations against Iran are “ahead of schedule.”

Uncategorized

Iranian Missile Strike on Beit Shemesh in Israel Kills 9

Emergency personnel work at the site of an Iranian strike, after Iran launched missile barrages following attacks by the US and Israel on Saturday, in Beit Shemesh, Israel, March 1, 2026. Photo: REUTERS/Ammar Awad

An Iranian missile strike hit the Israeli city of Beit Shemesh on Sunday, killing nine people and wounding dozens, in what authorities described as a direct impact on a public bomb shelter.

A ballistic missile leveled the bomb shelter, leaving a large crater in its wake. Most, if not all, of those killed had been taking cover inside the shelter when it hit, Jerusalem Police Deputy Commissioner Avshalom Peled said at the impact scene.

Those in critical condition were airlifted to Shaare Zedek Medical Center, a spokesperson for the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) said.

At least 20 people were still missing late on Sunday afternoon local time.

As you read this, an Iranian missile has just struck a residential neighborhood in Beit Shemesh, Israel, only 30 kilometers/about 18 miles from Jerusalem.

Nine people are dead.

More than 20 are wounded, including children. A

public shelter collapsed from the direct hit. An… pic.twitter.com/mEVDlPEqgf

— Ella Kenan (@EllaTravelsLove) March 1, 2026

Several buildings surrounding the shelter in Beit Shemesh, which is west of Jerusalem, were also damaged in the attack, with two collapsing entirely. A synagogue was also destroyed.

Emergency crews from Magen David Adom, ZAKA, and United Hatzalah joined fire and rescue units at the site, combing damaged buildings and debris for possible survivors. Many people were trapped under rubble or inside apartments, first responders said.

The Iranian Regime directly fired missiles toward the civilian neighborhood of Beit Shemesh, killing innocent civilians.

The Iranian regime purposely targets civilian targets while we precisely target terror targets. This is who we’re operating against—a regime who uses… pic.twitter.com/9W8Fp4T2tH

— Israel Defense Forces (@IDF) March 1, 2026

Chaim Wingarten, deputy director of operations at rescue organization ZAKA, described the scenes as “very difficult.”

“When I arrived, it was a huge chaos, with wounded people everywhere,” he said.

The strike was part of a larger volley that triggered air-raid sirens across the country. A man in his fifties was wounded by shrapnel elsewhere in central Israel.

IDF foreign media spokesman Lt. Col. Nadav Shoshani charged Iran with deliberately firing at civilians. “We know this is their strategy,” he said, adding that Israel would do “everything in our power to remove these capabilities from this bloodthirsty terrorist regime.”

The Beit Shemesh hit marked the highest single-incident death toll inside Israel since the confrontation with Iran began a day earlier. The previous peak came during the 12-day war in June 2025, when a missile slammed into an apartment block in Bat Yam and killed nine people.

The Beit Shemesh strike came a day after US and Israeli forces struck a compound in Tehran killing senior Iranian officials, including Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, whose death was later announced on Iranian state television.

In an interview with Fox News on Sunday, Trump said 48 Iranian leaders were killed in the strikes. “Nobody can believe the success we’re having; 48 leaders are gone in one shot. And it’s moving along rapidly,” he said.

Separately, the American president told CNBC that the US operation was “ahead of schedule.”

Thousands of Iranians braved the strikes and took to the streets to celebrate Khamenei’s death on Saturday evening. Many people stood on balconies and at windows chanting “freedom, freedom,” The New York Times reported. People in the Iranian city of Shiraz were “abandoning their cars for an impromptu dance party, whistling, cheering, clapping, and screaming with joy. In many videos, celebrants joined together in a cheer that is typically reserved for weddings, symbolizing pure joy,” the report said.

GeoConfirmed Iran.

People chanting – Celebrations through the Foolad Shahr area in Isfahan with joy and jubilation over the killing of Khamenei.

Rough location – 32.48169, 51.39167

F9JR+MMF Fuladshahr, Isfahan Province, IranGeoLocated by @Mitch_Ulrich

Geolocation:… https://t.co/iv9TlSPPfS

— GeoConfirmed (@GeoConfirmed) February 28, 2026

Can you hear the joy in his voice?

“I am dreaming, hello world!” pic.twitter.com/ICq77zBerv— William Mehrvarz (@WilliamMehrvarz) March 1, 2026

Iran retaliated by firing repeated waves of missiles and drones, with launches aimed not only at Israel but also at US bases in the Middle East, including Qatar, Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates, and Bahrain. Iran on Sunday morning also launched two missiles at Cyprus, where thousands of British military personnel are stationed, which fell short.

Later in the afternoon, the US acknowledged its first losses with US Central Command, saying three American service members were killed and five were seriously wounded during the operations in Iran.