Uncategorized

After three years in Israel, Reform convert told she can’t make aliyah

(JTA) — When Isabella Vinci stepped out of the mikvah on Nov. 11, 2021, she thought she had done everything that would be required to become Jewish. A beit din, or rabbinic court, had approved her conversion after nearly a year of study with Rabbi Andrue Kahn at Temple Emanu-El, a Reform congregation in New York, including a congregational course and one-on-one meetings.

Within a year, she visited Israel on Birthright and returned on an immersion program to teach English in an Orthodox public school in Netanya. Friends, rabbis and colleagues, she said, embraced her as Jewish.

Israel’s Population and Immigration Authority did not.

In a pair of decisions issued in January and again last month, immigration officials rejected Vinci’s application for aliyah under the Law of Return and then denied her administrative appeal.

The letters point to two main problems: She studied for conversion online during the COVID period, and she did not prove sufficient post-conversion participation in a synagogue community — particularly while living in Israel.

Vinci, 31, had to leave behind the life she had built in Tel Aviv and move back to the United States. She is now preparing a court petition with the Israel Religious Action Center, the legal‐advocacy arm of Reform Judaism in Israel.

For decades, IRAC and other non-Orthodox advocacy groups have complained about attempts by religious parties in Israel to block the recognition of conversions outside of Orthodoxy. But Vinci’s advocates say she was blocked from citizenship despite a Supreme Court ruling from 2005 allowing overseas conversions, regardless of denomination.

Her rejection also reflects a gap between the Diaspora and Israel, they say, in everything from religious practice to the adaptations made necessary by the pandemic.

“The whole world — from rabbis to strangers who hear my story — tells me I am Jewish. They see that I am putting everything on the line to be a part of our people. The only ones telling me that I’m not Jewish are within this government agency,” Vinci said in an interview, describing months of silence and what she felt was the government’s unwillingness to consider new supporting documents. “Why aren’t they putting in the work and the effort to actually understand where I’m coming from?”

Vinci grew up Catholic in a sprawling, multicultural family, spending early years in Florida and most of her childhood in Omaha, Neb. She never felt rooted in the church and developed her own spirituality as a teen. Jewish relatives and friends were part of her orbit, and she felt increasingly drawn to the religion.

When she moved to New York as an adult, she decided to become a Jew, going through Temple Emanu-El in Manhattan, one of the most prominent congregations of Reform Judaism.

Neither the immigration authority nor the Interior Ministry, which oversees it, responded to a request for comment.

But official responses Vinci received show that decisions in her case zero in on whether her path fits internal regulations drawn up in 2014 to vet conversions performed abroad. The Israeli Supreme Court ruled in 2005 that such conversions, regardless of denomination, must be recognized, leaving it to the ministry to set criteria.

Those rules anticipate in-person study anchored in a congregation; if the course is “outside” the congregation, they require a longer, 18-month track. In Vinci’s case, officials treated her 2020-2021 Zoom coursework as external and concluded she hadn’t met the time or community-involvement thresholds.

IRAC’s legal director for new immigrants, attorney Nicole Maor, appealed the initial rejection, sending in a detailed memo. Maor wrote that congregational classes conducted on Zoom during a pandemic should be considered congregational, rather than external. She argued that the criteria’s purpose is to prevent fictitious conversions — not to penalize sincere candidates who followed their synagogue’s rules during COVID.

“The entire purpose of the criteria is to protect against the abuse of the conversion process. A person who converted in 2021, came to Israel on a Masa program to contribute to Israel in 2022-2023, and stayed in Israel to work and support the country in its most difficult hour after Oct. 7 deserves better and more sympathetic treatment,” she wrote.

She also wrote that the ministry had ignored evidence of Vinci’s Jewish communal life in Israel, from school prayer with students to weekly Orthodox Shabbat meals with a host family.

As part of Vinci’s appeal packet, Kahn submitted a letter describing the cadence of Vinci’s studies: roughly five months in Temple Emanu-El’s Intro to Judaism course alongside his own one-on-one meetings beginning Dec. 21, 2020, and continuing “1-3 times a month for 2-3 hours” until her November 2021 conversion — about 11 months in total. He listed key books and practices he assigned and attested to her active participation in synagogue young-adult programming.

A host family in Netanya provided a letter saying Vinci spent “Shabbat with our family every weekend as well as most holidays,” describing a year of Orthodox observance in their home and an ongoing relationship since she moved to Tel Aviv after Masa. The school where she taught also wrote in support.

The ministry was unmoved.

In an interview, Maor, who handles a large caseload of prospective immigrants, said Vinci’s case is emblematic of a larger phenomenon.

“It’s not just bureaucracy,” Maor said. “There’s a recurring theme — a suspicious attitude at the ministry that has become worse in recent years and makes life much more difficult for converts.”

Vinci’s case sits at the fault line between Diaspora practice after COVID and Israeli bureaucracy. Around the world, Reform and Conservative congregations shifted classes, and in some communities, services, to Zoom. Many have retained hybrid models because they work for busy or far-flung learners.

“This reality has led to a widening gap between how Diaspora congregations operate and the demands of the Interior Ministry,” Maor said.

There is also a philosophical mismatch: For the ministry, involvement in the Jewish community post-conversion appears to mean synagogue membership and attendance logs. For non-Orthodox streams, Maor said, Jewish life can be expressed in multiple ways — home ritual, learning circles, social-justice work — especially in Israel, where Jewish rhythms permeate public life.

In Vinci’s Netanya year, that life included like daily school prayer, holidays with an observant host family, and teaching in a religious environment. Maor argues that should count.

Kahn, who says two of his other converts have made aliyah without incident, said he was saddened by Vinci’s rejection given her devotion and the hoops she jumped through to satisfy paperwork and timelines.

“It wasn’t like she was mucking around in Israel, she was really doing the work and legitimately devoted to being Jewish,” he said.

After losing her legal status and appeal, Vinci returned to the United States. She took a legal-assistant job in Kansas City and is scraping together fees to file a court petition.

Maor won’t predict the outcome, but she said often cases settle before a precedent is set. The state agrees to a compromise such as additional months of study, rather than risk a ruling that forces a policy shift.

Vinci hopes the case determines not only where she celebrates the next set of holidays, but also improves how Israel treats a growing cohort of would-be immigrants whose Jewish journeys began on a laptop during a once-in-a-century shutdown and amid rising antisemitism.

“I hope my story sheds light on inter-community love and acceptance,” she said. “In our current political and social climate, the best thing we can do is be united as one.”

The post After three years in Israel, Reform convert told she can’t make aliyah appeared first on The Forward.

Uncategorized

You could be imprisoned for praying at the Western Wall — and Bibi isn’t stopping it

Sometimes a single episode reveals much about the big picture. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s decision on Sunday to cancel a ministerial committee vote on legislation that would effectively criminalize egalitarian prayer at the Western Wall is one such moment. He was seeking to avoid friction with U.S. Jews on the day of a virtual appearance at an AIPAC event, but they should not be fooled: his coalition is in conflict with most of them.

The bill was backed by Justice Minister Yariv Levin of Netanyahu’s Likud, and its author, far-right coalition member Avi Maoz, is planning to table it for a Knesset vote Wednesday, even without official government backing. Whether or not it passes, it is an accurate window into the essence of the Netanyahu religious-right coalition.

The proposed bill would grant the ultra-Orthodox–controlled Chief Rabbinate exclusive authority to determine what constitutes “desecration” at Jewish holy sites, including the Western Wall, with violations punishable by five to seven years in prison. In practice, this would almost certainly place non-Orthodox streams of Judaism — Reform, Conservative, Reconstructionist — alongside Women of the Wall and other egalitarian prayer groups at legal risk for engaging in forms of worship embraced by millions of Jews worldwide.

Yes: Jews would face imprisonment for praying according to their tradition at Judaism’s most resonant site.

Netanyahu’s intervention, while politically astute, should not reassure anyone. He did not repudiate the legislation nor mobilize his party to bury it but rather postponed a committee vote that would have bound coalition members to support it. The bill remains alive, capable of advancing through Knesset procedures.

Only days earlier, Israel’s Supreme Court issued a ruling calling on the state and the Jerusalem municipality to act “with the requisite speed and diligence” to advance long-delayed renovations at the egalitarian prayer area known as Robinson’s Arch. The bill is the backlash, and it is the latest flareup in a legal dispute stretching back nearly a decade, to the Western Wall compromise approved in 2016.

That arrangement was designed to provide non-Orthodox streams with a larger, visible, and accessible prayer space under their own jurisdiction — a framework meant to respect Jewish pluralism and the diversity of Jewish practice around the world. But in 2017, under pressure from ultra-Orthodox coalition partners who do not recognize the legitimacy of Conservative and Reform Judaism, the compromise was scrapped by Netanyahu’s government, triggering a deep rupture with many Diaspora Jews.

After the compromise collapsed, petitions from the Reform and Conservative movements and Women of the Wall led the court to repeatedly prod the government to implement the egalitarian plaza upgrades. The state assured the court that renovations would proceed; the work was slated to take ten months. Nearly ten years later, the project sits unfinished.

Against this backdrop, the proposed legislation is a massive escalation that aims to deal a coup-de-grace to the project of bringing Jewish pluralism at the site. Yizhar Hess, vice chairman of the World Zionist Organization and former head of the Conservative-Masorti movement in Israel, called the bill “a declaration of war on world Jewry,” saying that it is “hard to think of a less Zionist, less Jewish and more damaging proposal.”

The Western Wall controversy is not just about prayer arrangements, containing an even larger lesson about what is in store in case of an election victory this year by the Netanyahu regime. At this point the word “regime” is appropriate, because the coalition is bound to change the character of the country, perhaps decisively.

First, the consolidation of ultra-Orthodox power will accelerate, pushing Israel closer to a functional theocracy. Religious parties have mastered the leverage that coalition arithmetic grants them, when there is a Likud-based rightist government, extracting concessions vastly disproportionate to their electoral weight. Each bargain yields further privileges: increased budgets for religious institutions, sweeping exemptions, expanded authority for religious courts, and now the potential criminalization of non-Orthodox worship at key sites. A law targeting egalitarian prayer would be a milestone.

Following that, non-Orthodox streams of Judaism — central to Jewish identity in the United States, Latin America, Europe, and beyond — will face growing marginalization. Diaspora Jews, most of whom identify with non-Orthodox traditions, understandably view such moves as assaults on their place within the Jewish collective. The damage this will cause Israel–Diaspora relations should be obvious – but many are not awake to the coming storm.

Moreover, this will soon expand into the lives of Israelis, where Orthodoxy (but not ultra-Orthodoxy) indeed holds away among those people, perhaps half the Jews, who are at all observant. The authority of rabbinical courts will expand further into civilian life. Israel already grants religious institutions significant power over personal status issues such as marriage, divorce, and burial. Coalition dynamics encourage relentless pressure for broader jurisdiction, deeper enforcement powers, and reduced secular oversight. Control over ritual space rarely ends there. It extends into family law, gender norms, educational frameworks, and public behavior. Efforts to enact some public transport and commerce on the Sabbath would be killed.

Another Netanyahu government can be expected to double down on territorial maximalism — especially settlement expansion — with the goal of making Israel’s entanglement with the West Bank irreversible. The likely result is not clean annexation but a de facto indivisible space containing two populations governed by unequal systems. This non-democratic binational reality is not the Jewish democracy envisioned by Israel’s founders and will be condemned by almost the entire world — including many in the United States — as a variant of apartheid. Israel can expect economic sanctions.

Finally, the coalition will see itself vindicated as regards its effort to eviscerate the independence of the court system – a project capped by the proposal to allow the Knesset to overturn court rulings, via a simple majority. That effort has been partly put on hold by the mass protests of 2023 and the years of war sparked by the Oct. 7 massacre. Expect it to return with a vengeance, aiming to turn Israel into an elected autocracy in the mold of Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s Turkey or Viktor Orban’s Hungary.

The Western Wall controversy should thus be read not as an isolated skirmish, but as a diagnostic event — a glimpse of a possible future that many Israelis and Jews worldwide would find profoundly troubling, and indeed potentially fatal to any possibility for wide Jewish support for Israel.

World Jewry should call Netanyahu to account on all these outrages.

The post You could be imprisoned for praying at the Western Wall — and Bibi isn’t stopping it appeared first on The Forward.

Uncategorized

Pro-Palestinian vandalism of London bakery with Jewish roots sparks outcry

(JTA) — A newly opened chain of a popular London bakery was vandalized on Wednesday following a pro-Palestinian protest that accused the company of “funding Israel.”

Gail’s Bakery, which operates roughly 170 locations throughout the United Kingdom, opened its new location in north London where it was met by a small group of protesters holding a large sign reading “Boycott Israel For Genocide And War Crimes in Gaza.” Another sign claimed the bakery was “funded by investors in apartheid,” according to a video of the protest posted online.

In the video posted on X, a Jewish bystander confronted the protest presence, asking, “Why are you protesting a U.K.-based business saying ‘Boycott Israel’? Is it because they’ve got Jewish directors?”

In response, a protester responded that the bakery’s profits were “going to private equity owners and investors” who had invested in Israeli “war tech.”

I’m not a fan of Gail’s because it’s not kind towards people who are gluten free but protesting a British company for ‘genocide’ because it was started by a Jew absolutely stinks.

This was Archway today. pic.twitter.com/TQuxzj0P84— Nicole Lampert (@nicolelampert) February 19, 2026

Following the protest, red paint was splattered on the bakery’s signage and facade along with the words “Boycott Gails, funds Israeli tech.”

London’s Metropolitan Police said that no arrests had been made in connection to the vandalism, and that police were “continuing to review other footage to identify any lines of enquiry that might help to identify the suspects.”

Gail’s was founded as a wholesale bakery by a team of Israeli bakers, including Gail Mejia and Ran Avidan, in the 1990s, and opened its first storefront bakery in 2005.

In 2021, the company was acquired by the American investment firm Bain Capital, which has invested in Israeli tech companies.

“We are a British business with no specific connections to any country or government outside the U.K.,” a spokesperson for Gail’s told the Jewish News. “Our focus right now is on working with the authorities and making sure our people feel safe and supported.”

Gail’s is not the first bakery with Israeli founders to be targeted by pro-Palestinian protesters in recent years. In the United States, the Israeli-inspired chain Tatte has drawn protests both in person and online, while the New York City Israeli bakery chain Breads recently faced unionization efforts that centered on the establishment’s “support of the genocide happening in Palestine.”

The vandalism of the new Gail’s quickly drew condemnation from Jewish leaders and groups in the U.K., who said it reflected a broader trend of hostility towards Jewish businesses.

“Targeting a business on the basis of alleged or perceived Israeli and or Jewish connections reflects a very worrying trend. Across the UK, companies and individuals are increasingly singled out by reference to their association real or otherwise to Israel, with an inevitable disproportionate impact on the Jewish community,” said a spokesperson for the Board of Deputies of British Jews. “That is not legitimate protest; it is creating an atmosphere of intimidation for Jewish businesses, staff and customers. And is part of a wider trend to try and drive Jews out of wider civil society.”

The European Jewish Congress called the vandalism “deeply concerning” in a post on X.

“Targeting a local business because of perceived Jewish or Israeli associations reflects a troubling normalization of hostility that must be firmly rejected,” the post read. “Such acts have no place in our societies and must be unequivocally condemned.”

British Labour party lawmaker David Taylor also decried the protest, writing in a post on X, “This is pure anti-semitism, no ifs, no buts.”

The post Pro-Palestinian vandalism of London bakery with Jewish roots sparks outcry appeared first on The Forward.

Uncategorized

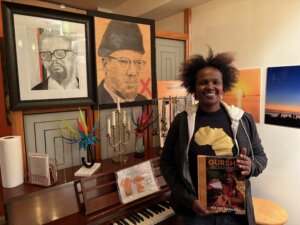

Ethiopian-American Jews lament loss of Harlem restaurant hub

For over a decade, Tsion Cafe, which owner Beejhy Barhany believes is the only Ethiopian Jewish restaurant in America, introduced patrons to injera, shakshuka spiced with berbere, and the flavors of Ethiopian-Jewish cuisine. But more than that, it introduced many patrons to Ethiopian Jews for the first time.

“I’ve been the ambassador, willingly or unwillingly,” Barhany said. “On the forefront, bringing and pushing for Jewish diversity.”

She recalled a moment that, for her, encapsulates the spirit of Tsion Cafe: feeding gursha — the Ethiopian tradition of placing food directly into someone’s mouth as a gesture of love — to an elderly Ashkenazi Jewish woman.

“She was open to receiving it! Someone who would never eat with their fingers,” Barhany said, laughing. “And she couldn’t stop.”

For Ethiopian Jews in America, a community numbering only a few hundred, Tsion Cafe was one of the only public-facing outposts of their heritage. But earlier this month, Barhany, who has been serving up Ethiopian Jewish delicacies to the Harlem community since 2014, announced on Instagram that she would close the restaurant’s dining room for “security reasons,” a move first reported by the New York Jewish Week.

Barhany told the Forward she has received “a lot of hate, phone calls, harassment,” including someone scrawling a swastika on the front of the restaurant. “You kind of push it aside, you disregard it. But at the end of the day, there is an impact emotionally, and it becomes a burden. I said to myself, ‘You know what? It’s just not worth it. It’s too much to deal with.’”

Despite the closure, Barhany remains determined to continue to share Ethiopian Jewish culture with patrons through catering and private events. “We are pivoting for security reasons because we have been threatened,” she said. “It’s not gone. We are reinventing ourselves. We are not giving up.”

The ‘October 8th Impact’

Barhany was born in Ethiopia and spent three years in a Sudanese refugee camp before moving to Israel in 1983, where she later served in the Israeli Defense Forces — a path shared by many Ethiopian Jews of her generation.

Ethiopian Jews lived for centuries in Ethiopia, maintaining ancient Jewish traditions and largely isolated from the broader Jewish world. In the 1980s and early 1990s, amid widespread instability in Ethiopia, Israel carried out dramatic covert airlift operations which brought tens of thousands of Ethiopian Jews to Israel. For many, their connection to Israel is rooted not only in longstanding religious tradition, but also in the lived experience of those rescue missions.

“Ethiopian Jews are very loyal to Jerusalem and to the people of Israel,” said Dr. Ephraim Isaac, an Ethiopian Jewish scholar based in New Jersey. “All the Ethiopian Jews I know living in America have relatives in Israel, and they go back and forth.”

When she arrived in New York in the early 2000s, Barhany was struck by how little awareness Americans had of the African Jewish diaspora. Wanting to educate her new neighbors about her background, and searching for a sense of “community and belonging,” she opened Tsion Cafe in 2014.

After the violent attacks on Israelis on October 7, 2023, Barhany said she felt the desire to be more public about her Judaism and her connection to Israel. “It was that October 8th impact. You just wanted to be a proud Jew,” she said. That impulse pushed her to make Tsion Cafe fully kosher and vegan. “I thought, ‘How can I have my people come here and feel comfortable?’ And also introduce Ethiopian food to people who never had it before.”

She also became more outspoken about her Jewish heritage and her connection to Israel, appearing in cooking videos with popular pro-Israel influencer Noa Tishby, and posting photos of herself at a pro-Israel rally shortly after the October 7 attacks. As pro-Palestinian protests unfolded across New York City, particularly on nearby college campuses like Columbia University, she said she understood that her outspokenness could make her a target.

But for Barhany, there was no other option. “I celebrated proudly and amplify my identity. I never shy away from that,” she said. “Otherwise I wouldn’t be true to myself.” She says her advocacy “happened organically, sincerely, genuinely, because who I am.” “I didn’t sign up for this,” she said, laughing. “But I am happy to engage with those people and maybe broaden their understanding of Jewish Diaspora.”

A small community, a singular space

For many in the United States’ small Ethiopian Jewish community, Tsion Cafe’s closure represents more than a business shift; it marks the disappearance of one of the only visible spaces representing their culture in America.

Isaac estimates the Ethiopian Jewish population in America numbers only a few hundred.“They came here just like other members of Israeli society,” he said, for education, work, or opportunity. Some say they came to the U.S. to get away from discrimination they experienced in Israel. The largest cluster, he noted, is in Jersey City, with smaller communities in Brooklyn and Queens. “We respect each other, we love each other, but never lost contact,” he said.

Barhany said that for many in the American Ethiopian Jewish community, Tsion Cafe was seen as “a home far away from home” with community members traveling from across the country to come to her restaurant. “We have people coming from D.C., L.A., you name it,” she said.

“I think a majority of Ethiopian Jews in America know Beejhy,” Isaac remarked. “The community is very upset by the closure. She is respected for all the efforts that she has undertaken.”

Tali Aynalem, a 34-year-old Ethiopian Jew who lives in Oregon, said Tsion Cafe challenged longstanding assumptions about what Jewish identity looks like in the U.S.. “In America, there is an idea of one way that a Jewish person looks like. I always sort of have to explain who I am. It’s not just understood.”

For Aynalem, Tsion Cafe was bringing to light the diversity of Jews and Israelis to an American audience. “She really was showing what Israel is all about, which is that we are so mixed because we’ve all been in exile in so many different places for so long. She showed that in her restaurant.”

But Aynalem sees the restaurant’s closure as part of a broader trend.“People are quick to say, ‘It’s a Black-owned business, it’s a small business, support it.’ But as long as there’s an intersection with Judaism, there’s no support,” she said. “It raises the question: do you care about Black people, or do you just not care about Jews, regardless of color?”

She added that, as an Ethiopian Jewish woman, she once believed her racial identity shielded her from certain forms of antisemitism.

“For a long time, I felt like that extra layer of being Black almost protected me, because people are scared of being called racist,” she said. “They’re not scared of being called antisemitic.”

In the wake of rising threats and Tsion Cafe’s closure, she said, that sense of insulation has faded.

“It shows you that antisemitism, regardless of what you look like, doesn’t really discriminate,” she said. “I don’t think I have that extra armor anymore. No one is really safe in this climate.”

Aynalem also worries that Ethiopian Jews in America are still understood primarily through the lens of rescue. She said that for many American Jews, the only thing they know about Ethiopian Jews is stories of the dramatic operations that brought them to Israel.

“We’re past that,” she said. “Let’s talk about my generation. We’re part of the culture. People are eating injera, that’s a normal occurrence within Israeli culture now.” For Tali, Tsion Cafe was doing exactly that.

Barhany agrees.

“I always see articles about Ethiopian Jews being rescued,” she said. “I’m kind of fed up with that.” For her, Tsion Cafe was a way to “bring something more positive and more unifying” to the American conversation about Ethiopian Jewish life.

Not just for Ethiopian Jews

Rabbi Mira Rivera of JCC Harlem said Tsion Cafe was woven into the fabric of Jewish life in the neighborhood. “The Ethiopian Jews in Harlem aren’t going anywhere,” she said. “But it was always a joy to have a bastion, a place where you’d say, ‘Let’s meet at Tsion Cafe. Let’s celebrate your birthday there.’ It was part of living in Harlem.”

She compared Tsion Cafe to the Ethiopian Jewish neighborhoods she had visited in Israel, places where a community had a visible center. “This was that place,” she said. “It was where people gathered. Over the years, they changed to vegan and kosher so that the larger Jewish community would start to understand and partake in their culture.” She continued, “to not have that place where all the families can go, it’s really hard.”

But for Barhany, Tsion Cafe was never meant to be “just a cafe.” “I didn’t want it to be a regular cafe where you go in, sit, pay, and go,” she said. “It’s a place where people can nourish and engage in grown-up conversation.”

Amid antisemitic threats, she remains more committed to that mission than ever. Barhany plans to host interfaith gatherings and travel the country to share the flavors and stories of Ethiopian Jewish culture.

“If I can facilitate dialogue, I would be honored,” she said.

“We are not giving up. We are still here. We’re just coming in a different shape or form.”

The post Ethiopian-American Jews lament loss of Harlem restaurant hub appeared first on The Forward.