Uncategorized

“I feel my father all the time”

פֿון פּאָלינאַ בעלענקי

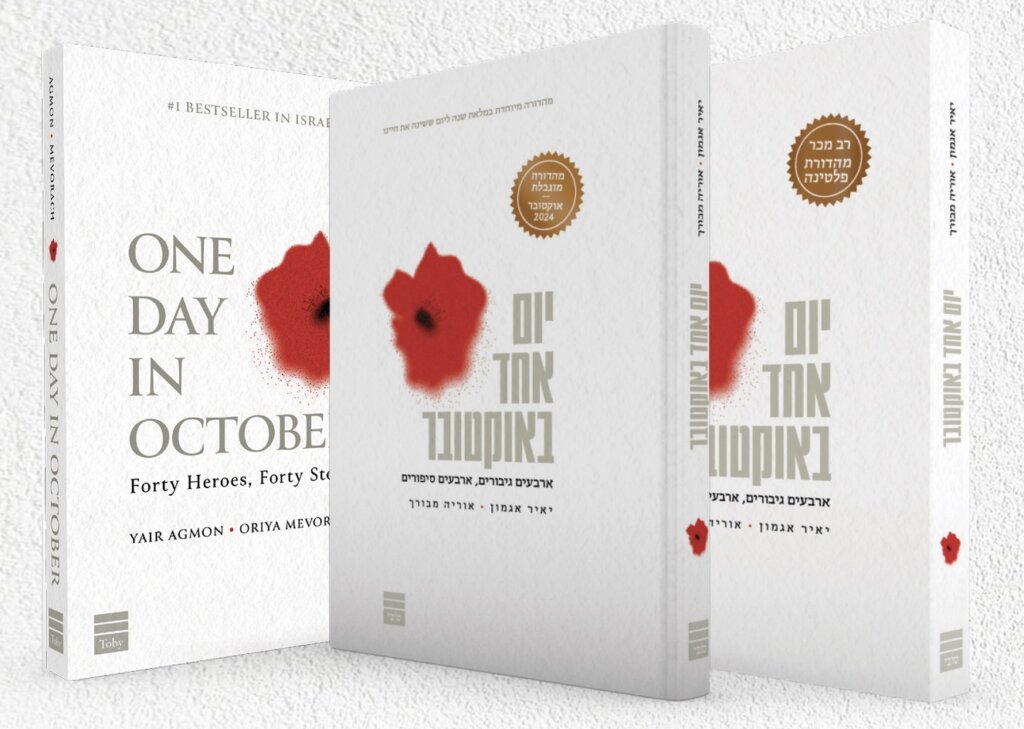

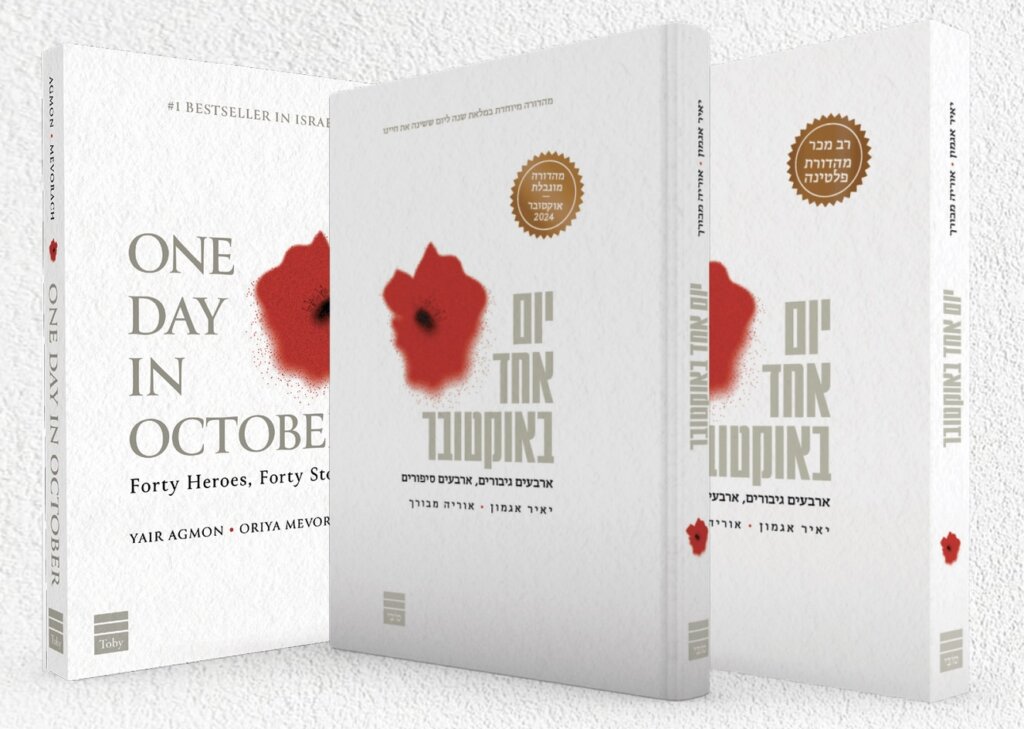

אין מאַרץ 2024 איז אַרויס אין ישׂראל אַ בוך מיטן טיטל „איין טאָג אין אָקטאָבער“. די מחברים יאיר אַגמון און אוריה מבורך האָבן אין אים אַרויסגעגעבן 40 עדותשאַפֿטן פֿון דעם 7טן אָקטאָבער 2023. דאָס זענען 40 טעקסטן וואָס דערציילן פּערזענלעכע זכרונות פֿון מענטשן וואָס דער דאָזיקער שרעקלעכער טאָג האָט זיי דירעקט טראַגיש געטראָפֿן, אָדער ווײַל זיי האָבן אַליין איבערגעלעבט דעם כאַמאַס־טעראָר אין דרום־ישׂראל אָדער ווײַל זיי זײַנען בײַ אים אומגעקומען און איבערגעלאָזט קרובֿים, באַקאַנטע אָדער פֿרײַנד, וואָס זײַנען גרייט געווען צו פֿאַרשרײַבן זייערע זכרונות וועגן דעם אומגעקומענעם.

די מעשׂיות זײַנען פֿאַרשריבן אין דער ערשטער פּערזאָן וואָס מאַכט זיי קלינגען ווי אַ פֿאַרציילטע מעשׂה. אין דער אמתן זײַנען די טעקסטן באַאַרבעטונגען פֿון אינטערוויוען. די צוויי מחברים זײַנען די רעדאַקטאָרן און האָבן געאַרבעט לויט צוויי הויפּטפּרינציפּן: אָפּצוהיטן ווי צום געטרײַסטן דאָס אויטענטישע קול פֿון דעם יחיד וואָס דערציילט און גלײַכצײַטיק צו געשטאַלטיקן דעם טעקסט — אויך אַ ביסל ליטעראַריש — פֿאַרן לייענער.

דאָס בוך שפּיגלט אָפּ אַ ברייטע גאַמע קרבנות פֿונעם 7טן אָקטאָבער — קינדער און זקנים, פֿרויען און מענער, ייִדן און אַראַבער, ישׂראלים און אויסלענדער. געציילטע חדשים נאָכן פּובליקירן דעם העברעיִשן מקור זײַנען אַרויס איבערזעצונגען אין נישט ווינציק שפּראַכן. די מחברים אָבער איז גאָר וויכטיק דווקא איין באַזונדערע איבערזעצונג: אויף ייִדיש. אַזאַ האַלט מען איצט אין צוגרייטן.

כּדי אָפּצומערקן דעם אָנדענק פֿון אַלע ברוטאַל און אומשולדיק אומגעברענגטע קרבנות פֿון יענעם טעראָריסטישן אַטאַק — פּובליקירט דער פֿאָרווערטס דאָ צום ערשטן מאָל אַן אָפּקלײַב פֿון דער דאָזיקער ייִדישער איבערזעצונג. דער הײַנטיקער טעקסט — פֿון פּאָלינאַ, אַ 14־יאָריק מיידל אין אופֿקים, וואָס איר טאַטע, אַ פּאָליציאַנט מיטן נאָמען דעניס בעלענקי, וואָס איז אומגעקומען קעמפֿדיק קעגן די טעראָריסטן — איז דער ערשטער אין אַ סעריע וואָס מען וועט קענען לייענען אין די ווײַטערדיקע טעג און וואָכן.

לאָמיר האָפֿן אַז בשעת מיר געדענקען די קרבנות דורך די אָ עדותשאַפֿטן וועלן צוריקקומען אַלע לעצטע לעבעדיקע פֿאַרכאַפּטע וואָס די כאַמאַס־טעראָריסטן האַלטן שוין צוויי יאָר אין אוממענטשלעכע און פֿאַרברעכערישע באַדינגונגען אין עזה. לאָמיר נישט פֿאַרגעסן!

– מרים טרין

1.

מײַן טאַטע האָט זייער ליב געהאַט מוזיק, און אין זײַן פֿרײַער צײַט, ווען ער האָט נישט געאַרבעט בײַ דער פּאָליציי, פֿלעגט ער זיצן און שפּילן אויף דער גיטאַרע. און איין טאָג ווען איך בין געווען אַכט יאָר אַלט, האָט ער מיך באַקענט מיט אַ זינגערין וואָס ער האָט ליב געהאַט, אַ רוסישע זינגערין וואָס הייסט מאָנעטאָטשקאַ און איך בין געווען אין גאַנצן באַגײַסטערט און ממש ליב געקראָגן אירע לידער, און יעדעס מאָל וואָס מיר זײַנען געפֿאָרן אין אויטאָ פֿלעגן דער טאַטע און איך אָנשטעלן אירע לידער און זינגען, קאַראַאָקע און אַזוינס. און דוכט זיך מיר מיט אַ יאָר צוריק איז די אָ זינגערין געקומען קיין ישׂראל צום ערשטן מאָל! און פֿאַרשטייט זיך האָבן מיר געקויפֿט בילעטן און געגאַנגען אַהין, און דאָס איז געווען ממש wow, ס׳איז געווען אַ גוואַלדיקער קאָנצערט, איך האָב אַזוי ווילד אַרומגעטאַנצט פֿון פֿאָרנט בײַ דער בינע און ער האָט מיר אונטערגעטראָגן אַ קאָלאַ אָדער אַן אַנדער געטראַנק און מיך געהיט פֿון הינטן. אָבער ווען איך האָב זיך אומגעקוקט אויף אים האָב איך געזען אַז אויך ער זינגט מיט אַלע לידער, כאַ כאַ כאַ.

איך בין הײַנט 14 יאָר אַלט. ווען דער טאַטע איז געווען אַן ערך אין מײַן עלטער איז ער געקומען קיין ישׂראל. ער און די מאַמע האָבן זיך געטראָפֿן דורך אַ קאָמפּיוטער־שפּיל! און זי האָט עולה געווען צוליב אים. איך האָב צוויי שוועסטער־ברידער, אַן עלטערע שוועסטער וואָס וווינט אין תּל־אָבֿיבֿ און אַ קליינעם ברודער מיט אונדז אין שטוב, בין איך אַ ביסל ווי אַ גרויסע שוועסטער. מײַן טאַטע איז שוין לאַנגע יאָרן אַ פּאָליציאַנט און די אַרבעט פֿון פּאָליציאַנטן איז ממש־ממש שווער. איז ער באמת נאָר אויף אַ העלפֿט אין דער היים.

ער איז געווען אַ טאַטע איינער אין דער וועלט! אַזאַ פֿריילעכער מענטש, אומעטום האָט ער פֿאַרשפּרייט שׂימחה, געוווּסט ווי אַזוי צו מאַכן אַ ליכטיקערע שטימונג, ווי צוצוגיין און צו רעדן צו מענטשן. און מיר האָבן געהאַט אַ קליינעם גאָרטן. האָט ער ממש ליב געהאַט דאָרט צו זאָרגן פֿאַר די בלומען, פֿלאַנצן, האָט דאָרט פֿאַרפֿלאַנצט פֿרוכטביימער און מיט אונדז אַפֿילו געהאָדעוועט טרוסקאַפֿקעס.

ער האָט אויכעט ליב געהאַט הינט. ווען איך בין געווען עלף יאָר אַלט האָב איך באַקומען פֿון טאַטע־מאַמע צום געבורטסטאָג פּעפּסי, אַ קליינע, זיסינקע הינטיכע, אַ געלע און ברוין־מאַראַנץ־קאָליריקע. און דער טאַטע איז געווען משוגע נאָך איר. ער האָט זיך תּמיד געשפּילט מיט איר, זיך יאָגן מיט איר, זי נעמען צום וועטערינאַר צוליב יעדער קלייניקייט און פֿלעג ווילדעווען מיט איר און אַרומשטיפֿן.

ער איז באמת געווען אַ ביסעלע משוגע און זייער קאָמיש. אום יום־טובֿ, ווי נאָווי גאָד למשל, פֿלעג ער זײַן דער וואָס דערציילט וויצן בײַם טיש, דערציילט מעשׂיות.

ער האָט מיך אונטערגעשטיצט אין אַלצדינג, די גאַנצע צײַט. און ער איז תּמיד געווען שטאָלץ מיט מיר, מיט דעם וואָס איך טו, נישטאָ קיין ווערטער דאָס צו דערקלערן. אמת, נישטאָ קיין ווערטער צו באַשרײַבן ווי וווּנדערלעך ער איז געווען, מײַן טאַטע.

שבת אין דער פֿרי האָבן זיך אָנגעהויבן די סירענעס. זײַנען איך, די מאַמע און מײַן ברודער גלײַך אַרײַן אינעם שוצצימער און דער טאַטע איז פּונקט געווען אויף נאַכטשיכט אין שׂדרות. ער האָט געדאַרפֿט צוריקקומען אַהיים אַרום זיבן אין דער פֿרי. און אַז מיר זײַנען שוין געווען אינעם שוצצימער האָב איך געעפֿנט דעם טעלעפֿאָן און איך זע אויף וואַצאַפּ פֿילמעלעך פֿון טעראָריסטן, דאָ בײַ אונדז אין אופֿקים! און איך האָב געזען אַ ווידעאָס פֿון טעראָריסטן וואָס שיסן אויף אַ פּאָליציי־אויטאָ, און כ’האָב זיך ממש דערשראָקן, אַז דאָס איז מײַן טאַטע, האָבן מיר אים אָנגעקלונגען און ער האָט געזאָגט אַז ער וועט זיך אַ ביסל זאַמען און איך האָב זיך געפֿרייט אַז ער לעבט.

אין צווישן איז אין דער אָ צײַט פֿון זײַן זײַט געפֿאַלן אַ ראַקעט אויף אַ הויז אין שׂדרות און ער איז געפֿאָרן מיט זײַן מאַנשאַפֿט קאָנטראָלירן וואָס עס טוט זיך דאָרט און דאַן, נאָך געציילטע מינוטן האָט ער אונדז אָנגעקלונגען און געזאָגט אַז מע שיסט דאָ, און געבעטן, מיר זאָלן אים מער נישט אָנקלינגען. דאָס איז געווען פֿאַרטאָג.

און שוין, דאָס איז געווען אונדזער לעצטער שמועס מיט אים.

וואָס עס איז געשען איז, אַז אין דער צײַט ווען זיי זײַנען געפֿאָרן אַ קוק געבן מכּוחן ראַקעט, האָבן זיי באַקומען אָנזאָגן, אַז עס זײַנען דאָ טעראָריסטן אויף דער פּאָליצײ־סטאַנציע פֿון שׂדרות. האָט ער דעמאָלט באַשלאָסן מיט זײַן מאַנשאַפֿט זיך אומצוקערן און איז צוריק אַהין. און ער האָט אויך באַשלאָסן, אַז עס איז ריכטיקער צו גיין צו פֿוס ווי צו פֿאָרן מיטן אויטאָ, ווײַל אַן אויטאָ, דאָס איז אַ מין גרויס לאָקערל פֿאַר די טעראָריסטן, אַן אויטאָ איז גרויס, מע קען אים זען. האָבן זיי זיך גענומען דערנעענטערן צו דער סטאַנציע. און דאָרט, אויף דער סטאַנציע אין שׂדרות איז געווען אַ גרויסע שלאַכט, מע קען זען אויף די בילדער, וואָס עס איז געבליבן פֿון דער סטאַנציע בײַם סוף פֿון די קאַמפֿן וואָס זײַנען דאָרט געווען.

און איידער זיי זײַנען אָנגעקומען אויף דער סטאַנציע, האָבן זיי געזען אַז עס זײַנען דאָרט דאָ טעראָריסטן אינעווייניק. און עס איז דאָרט געווען אַן אַנדער פּאָליציאַנט, אָן אַ וואָפֿן, וואָס האָט געהאַלטן בײַם אַרײַנגיין אין דער סטאַנציע כּדי זיך צו רעגיסטרירן און אָפּנעמען אַ וואָפֿן צי עפּעס אַזוינס, און מײַן טאַטע האָט אים אָפּגעשטעלט און אים געזאָגט נישט אַרײַנצוגיין, ווײַל עס זײַנען דאָ טעראָריסטן אינעווייניק. און אויפֿן טאַטנס לוויה איז דער אָ פּאָליציאַנט געקומען צו מיר און מיר געזאָגט, אַז ווען נישט מײַן טאַטע וואָלט ער הײַנט געווען טויט.

און דערנאָך זײַנען זיי אַרײַן אין דער סטאַנציע. זיי זײַנען געווען פֿיר פּאָליציאַנטן. און די טעראָריסטן וואָס זײַנען געווען אין דער סטאַנציע האָבן געשאָסן אויף זיי, פֿון סאַמע אויבן אויף די טרעפּ און פּשוט געפּרוּווט זיי אומברענגען ווי צום גיכסטן. נאָר מײַן טאַטע האָט נישט מוותּר געווען און נישט אַנטלאָפֿן פֿון דאָרט, ער האָט דאָרט צוריקגעשאָסן צוזאַמען מיט זײַנע פֿרײַנד, זיי האָבן כּסדר געשאָסן, זאַלבע פֿערט נישט אויפֿגעהערט צו שיסן. און אין עפּעס אַ מאָמענט האָט ער זיך אָפּגעזונדערט פֿון די אַנדערע פּאָליציאַנטן, אויף אַ זײַט, און דאַן האָט מען אים געטראָפֿן.

די גאַנצע מעשׂה האָבן מיר געהערט פֿון די פּאָליציאַנטן וואָס זײַנען דאָ געווען מיט אַ חודש צוריק, זיי זײַנען געקומען צו אונדז און אונדז אַלץ דערציילט. איין פּאָליציאַנטקע האָט אונדז דערציילט אַז אין דעם טאַטנס זכות איז זי געבליבן לעבן, ווײַל ער האָט זי געשיצט, אַ האַנטגראַנאַט זאָל זי נישט טרעפֿן. זיי האָבן אויך געוואָרפֿן אויף זיי [די טעראָריסטן) גראַנאַטן. און אַן אַנדער פּאָליציאַנט האָט אונדז דערציילט, אַז אַפֿילו נאָך דעם ווי מע האָט געטראָפֿן מײַן טאַטן, אַפֿילו ווען ער איז שוין געלעגן דאָרט אויף דער פּאָדלאָגע, האָט ער ווײַטער געקעמפֿט און געשאָסן אויף די טעראָריסטן. און דער אָ פּאָליציאַנט האָט אויך געזאָגט מײַן מאַמען אויף דער שיבֿעה, ער איז צוגעקומען צו איר און איר געזאָגט: „איך בין דער לעצטער וואָס האָט געזען דעניסן. ער האָט מיך פּשוט געראַטעוועט דאָרט.“ און די מאַמע און איך זײַנען געווען דערשיטערט.

איך האָב נאָך אַלץ נישט דאָס געפֿיל, אַז איך ווייס אַלצדינג, מיט אַלע פּיטשעווקעס, און איך בין נישט זיכער, אַז איך וויל וויסן, כ׳ווייס… אפֿשר וועט מיר דאָס נאָר נאָך מער וויי טאָן, איך ווייס נישט. איך ווייס, אַז מײַן טאַטע האָט געראַטעוועט מענטשן. און איך ווייס, אַז ער איז געווען מוטיק, אַז ער האָט באמת באמת געקעמפֿט, ביז דער לעצטער רגע. און איך בין שטאָלץ מיט אים, וואָס ער האָט דאָס געטאָן. אָבער עס איז טרויעריק, עס איז טרויעריק, ווײַל איך וואָלט געוואָלט ער זאָל אויך האָבן געראַטעוועט זיך אַליין.

4.

לעצטנס זאָגן מיר אַ סך מענטשן אַז איך בין ענלעך אויפֿן טאַטן. תּמיד פֿלעג מען אונדז זאָגן, אַז מיר זײַנען ענלעך, ביידע האָבן מיר אַ נאָז אַזאַ, כאַ כאַ כאַ, אָבער מיר זײַנען ענלעך אויך אין אַנדערע פּונקטן, למשל, איך פֿיל אַז אויך איך, אַזוי ווי ער, אויך איך קען צוגיין צו יעדן מענטשן און גרינג שאַפֿן מיט אים אַ פֿאַרבינדונג, געפֿינען דעם ריכטיקן צוגאַנג צו יעדן איינעם. און איך פֿאַרמאָג אויך יענע שׂימחה וואָס ער האָט געהאַט אין זיך. ער איז געווען אַ פֿריילעכער מענטש. און אַפֿילו איצט, ווען ער איז נישט מיט אונדז, אַפֿילו איצט פֿיל איך אַז איך טראָג זײַן שׂימחה אין זיך, ווי די שׂימחה וואָס איך האָב פֿון אים באַקומען וואָלט מיך געשיצט.

איך דערמאָן זיך אין אַ סך זאַכן וואָס מײַן טאַטע און איך האָבן געטאָן צוזאַמען, אין כּלערליי הנאהדיקע רגעס וואָס מיר האָבן געהאַט און ווען איך דערמאָן זיך דערין ווער איך פֿריילעך, אָבער דאַן דערמאָן איך זיך אַז ער איז מער נישטאָ און אַז איך וועל מער נישט האָבן אַזעלכע זכרונות. איך געדענק למשל, אַז איין מאָל האָב איך אויספּראָבירט אַ נײַע שמינקע און דאַן האָב איך זי אים געוויזן און געזאָגט: „גיב אַ קוק ווי אויסערגעוויינטלעך!“ און ער האָט זיך גענומען מיר עצהן: „זע, דאָ דאַרפֿסטו ניצן מער רויט און דאָ צוגעבן נאָך מער.“ און ער האָט מיר באמת געהאָלפֿן זיך שמינקען בעסער און דאָס איז געווען אַ סורפּריז, ווײַל ס׳איז דאָך — ביסט דאָך אַ טאַטע! טאָ וואָס עפּעס, ווי פֿאַרשטייסטו זיך אויף שמינקע?! כאַ כאַ כאַ.

און דאָס טוט באמת וויי. ס׳איז מיר שווער. ס׳איז מיר זייער שווער און איך פּרוּוו זיך אַן עצה געבן. מע קען זיך נישט באמת קיין עצה געבן מיט דעם. אָבער איך וועל זיך צו ביסלעך, צו ביסלעך אַן עצה געבן. איך ווייס אַז מיר קענען קריגן פּסיכאָלאָגן פֿרײַ פֿון אָפּצאָל, איך גיי נישט, ווײַל איך פֿיל זיך נישט באמת באַקוועם דערמיט. אפֿשר וועל איך גיין אין דער צוקונפֿט. איך האָב פֿרײַנד וואָס גייען יאָ. און איך האָב עטלעכע פֿרײַנד וואָס אויך זייערע קרובֿים זײַנען דערהרגעט געוואָרן יענעם טאָג, שעפּן מיר כּוח איינער פֿון צווייטן. מיר שטאַרקן זיך. און אויך דער מאַמע, אויך איר איז שרעקלעך שווער, איך און מײַן ברודער פּרוּוון איר ממש אונטערגעבן כּוח. ווען מיר זײַנען אין דער היים פּרוּוון מיר זײַן מיט איר ווי צום מערסטן און אַזוינס.

איך פֿיל דעם טאַטן די גאַנצע צײַט. אַ מאָל קומט ער פּלוצעם צו מיר אין חלום בײַ נאַכט, עס חלומט זיך מיר אַז ער פּרוּווט קאָמוניקירן מיט מיר, ער זאָגט מיר אַז ער איז שטאָלץ מיט מיר, מיט דעם וואָס איך טו איצט, דערמיט וואָס איך בין צוריק צו די לימודים, וואָס איך בין צוריק צום ראָבאָטיק־קורס, אַז איך בין ווידער אין „קרעמבאָ־פֿליגל“*, און אַז איך באַטייליק זיך אין נאָך אַנדערע קרײַזן.

אין דער וואָך ווען דאָס האָט פּאַסירט, האָט זיך מיר געחלומט אַז ער קומט צו אונדז, אַזוי זיך, נעמט אונדז אַרום, און זאָגט אונדז אַז דאָס אַלץ איז בלויז געווען אַן אַקציע אַזאַ און אַז ער האָט זיך געדאַרפֿט מאַכן טויט און אַז ער איז למעשׂה נישט באמת טויט. און ער האָט אונדז געהאַלדזט אין דעם חלום און דאָס איז געווען ממש־ממש רירנדיק. איך האַלט די דאָזיקע האַלדזונג כּסדר מיט זיך.

איך פֿריי זיך ממש זייער אַז מען האָט מיר פֿאָרגעלייגט צו שרײַבן וועגן מײַן טאַטן אין דעם בוך. דאָס איז מיר ממש וויכטיק. דאָס איז מיר באמת וויכטיק. איך האָב זיך ממש געפֿילט גערירט, ווען איך האָב באַקומען די ידיעה. און איך ווייס אַז איין טאָג וועלן מײַנע קינדער — זיי וועלן נישט קענען זען דעם זיידן אין דער צוקונפֿט, מילא, וועלן זיי אים נישט קענען, אָבער זיי וועלן כאָטש הערן וועגן אים. און זיי וועלן וויסן אַז ער איז געווען אַ גוטער מענטש, פֿריילעך און קאָמיש. איז אַ דאַנק אײַך, דאָס איז מיר באמת וויכטיק, מע זאָל אים געדענקען אויף ווײַטערדיקע דורות.

–––––––––––

* אַן אַלטערנאַטיווע ישׂראלדיקע יוגנט־באַוועגונג וואָס באַזירט זיך אויף גלײַכע רעכט פֿאַר קינדער מיט און אָן ספּעציעלע באַדערפֿענישן, געגרינדט אין 2002. מער אינפֿאָרמאַציע קען מען געפֿינען דאָ: krembo.org.

— איבערגעזעצט פֿון מרים טרין

The post “I feel my father all the time” appeared first on The Forward.

Uncategorized

Tucker’s Ideas About Jews Come from Darkest Corners of the Internet, Says Huckabee After Combative Interview

US Ambassador to Israel Mike Huckabee looks on during the day he visits the Western Wall, Judaism’s holiest prayer site, in Jerusalem’s Old City, April 18, 2025. Photo: REUTERS/Ronen Zvulun

i24 News – In a combative interview with US Ambassador to Israel Mike Huckabee, right-wing firebrand Tucker Carlson made a host of contentious and often demonstrably false claims that quickly went viral online. Huckabee, who repeatedly challenged the former Fox News star during the interview, subsequently made a long post on X, identifying a pattern of bad-faith arguments, distortions and conspiracies in Carlson’s rhetorical style.

Huckabee pointed out his words were not accorded by Carlson the same degree of attention and curiosity the anchor evinced toward such unsavory characters as “the little Nazi sympathizer Nick Fuentes or the guy who thought Hitler was the good guy and Churchill the bad guy.”

“What I wasn’t anticipating was a lengthy series of questions where he seemed to be insinuating that the Jews of today aren’t really same people as the Jews of the Bible,” Huckabee wrote, adding that Tucker’s obsession with conspiracies regarding the provenance of Ashkenazi Jews obscured the fact that most Israeli Jews were refugees from the Arab and Muslim world.

The idea that Ashkenazi Jews are an Asiatic tribe who invented a false ancestry “gained traction in the 80’s and 90’s with David Duke and other Klansmen and neo-Nazis,” Huckabee wrote. “It has really caught fire in recent years on the Internet and social media, mostly from some of the most overt antisemites and Jew haters you can find.”

Carlson branded Israel “probably the most violent country on earth” and cited the false claim that Israel President Isaac Herzog had visited the infamous island of the late, disgraced sex offender Jeffrey Epstein.

“The current president of Israel, whom I know you know, apparently was at ‘pedo island.’ That’s what it says,” Carlson said, citing a debunked claim made by The Times reporter Gabrielle Weiniger. “Still-living, high-level Israeli officials are directly implicated in Epstein’s life, if not his crimes, so I think you’d be following this.”

Another misleading claim made by Carlson was that there were more Christians in Qatar than in Israel.

Uncategorized

Pezeshkian Says Iran Will Not Bow to Pressure Amid US Nuclear Talks

Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian attends the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) Summit 2025, in Tianjin, China, September 1, 2025. Iran’s Presidential website/WANA (West Asia News Agency)/Handout via REUTERS

Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian said on Saturday that his country would not bow its head to pressure from world powers amid nuclear talks with the United States.

“World powers are lining up to force us to bow our heads… but we will not bow our heads despite all the problems that they are creating for us,” Pezeshkian said in a speech carried live by state TV.

Uncategorized

Italy’s RAI Apologizes after Latest Gaffe Targets Israeli Bobsleigh Team

Milano Cortina 2026 Olympics – Bobsleigh – 4-man Heat 1 – Cortina Sliding Centre, Cortina d’Ampezzo, Italy – February 21, 2026. Adam Edelman of Israel, Menachem Chen of Israel, Uri Zisman of Israel, Omer Katz of Israel in action during Heat 1. Photo: REUTERS/Athit Perawongmetha

Italy’s state broadcaster RAI was forced to apologize to the Jewish community on Saturday after an off‑air remark advising its producers to “avoid” the Israeli crew was broadcast before coverage of the Four-Man bobsleigh event at the Winter Olympics.

The head of RAI’s sports division had already resigned earlier in the week after his error-ridden commentary at the Milano Cortina 2026 opening ceremony two weeks ago triggered a revolt among its journalists.

On Saturday, viewers heard “Let’s avoid crew number 21, which is the Israeli one” and then “no, because …” before the sound was cut off.

RAI CEO Giampaolo Rossi said the incident represented a “serious” breach of the principles of impartiality, respect and inclusion that should guide the public broadcaster.

He added that RAI had opened an internal inquiry to swiftly determine any responsibility and any potential disciplinary procedures.

In a separate statement RAI’s board of directors condemned the remark as “unacceptable.”

The board apologized to the Jewish community, the athletes involved and all viewers who felt offended.

RAI is the country’s largest media organization and operates national television, radio and digital news services.

The union representing RAI journalists, Usigrai, had said Paolo Petrecca’s opening ceremony commentary had dealt “a serious blow” to the company’s credibility.

His missteps included misidentifying venues and public figures, and making comments about national teams that were widely criticized.