Uncategorized

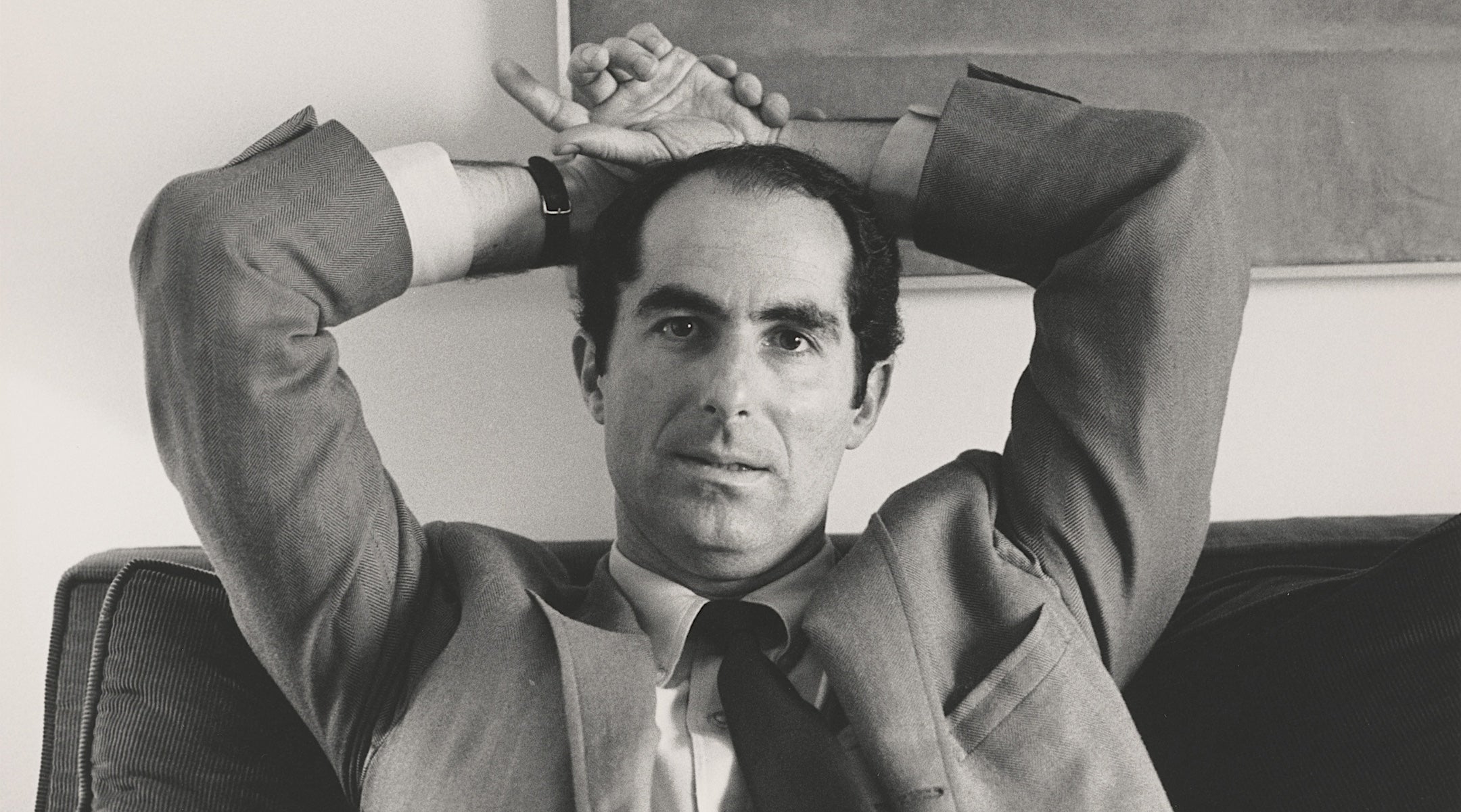

Philip Roth’s latest biographer wants Jews to read him again — without the guilt

It was a scandal right out of a Philip Roth novel: Days after the publication in 2021 of his long-awaited biography of Roth, author Blake Bailey was credibly accused of sexual misconduct. The publisher pulled the book, pulping all the copies.

Even before the uproar, many younger readers lumped Roth among the “great white males” of mid-20th-century literature, and throughout his career Roth was dogged by accusations that he was a misogynist, both in his fiction and his private life. The scandal seemed to confirm these accusations by proxy, conflating the author and his biographer.

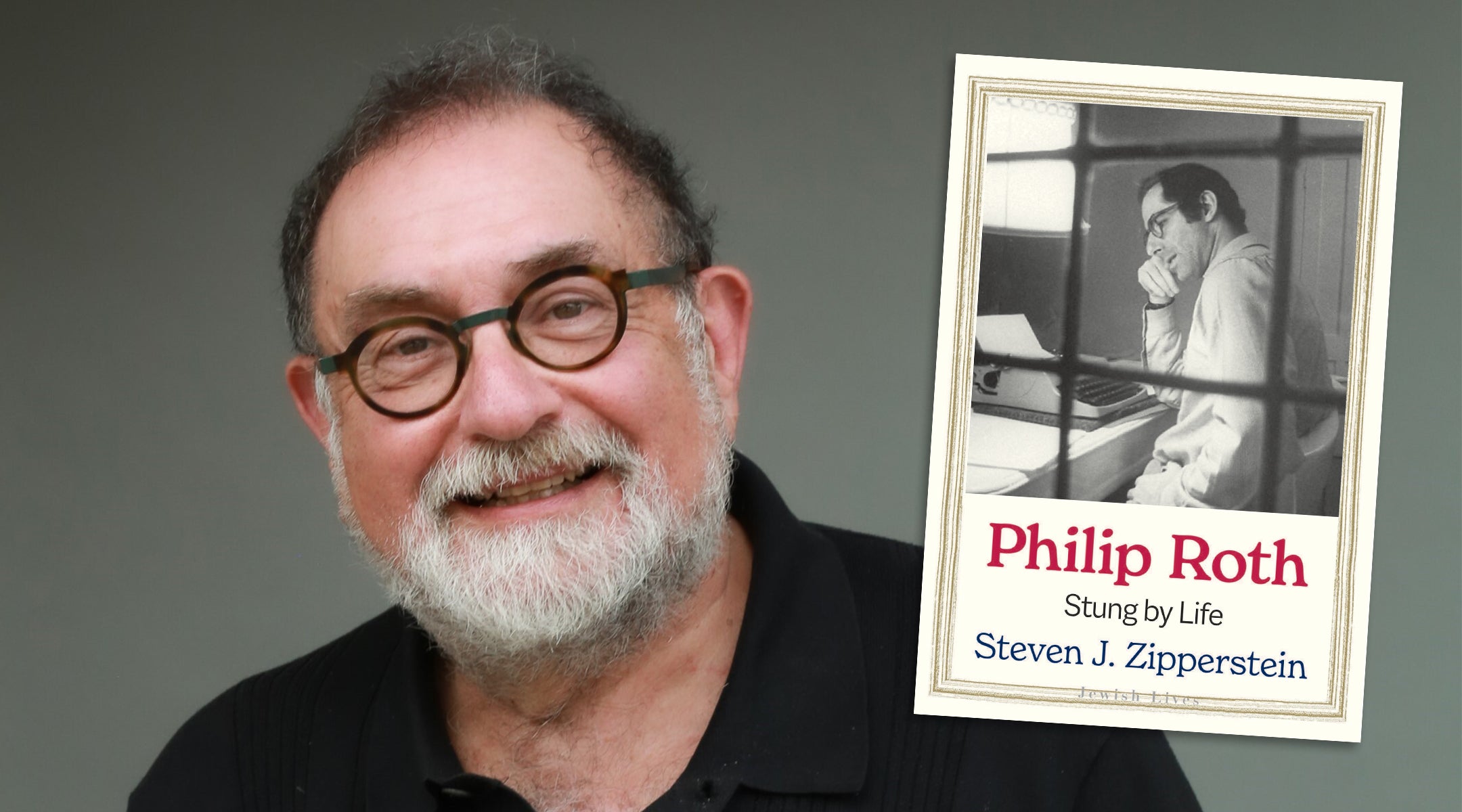

Stanford historian Steven J. Zipperstein had already begun his own biography of Roth before the author died in 2018 and while Bailey’s book was under contract. “Philip Roth: Stung by Life,” part of Yale University Press’s “Jewish Lives” series, isn’t meant as a corrective to Bailey’s book or the fallout. But it does argue why Roth remains relevant and vital, especially to current Jewish discourse.

Writes Zipperstein: “He would probe nearly every aspect of contemporary Jewish life: the passions of Jewish childhood, the pleasures and anguish of postwar Jewish suburbia, Israel, diaspora, the Holocaust, circumcision, the interplay between the nice Jewish boy and the turbulent one deep inside.”

Zipperstein is the Daniel E. Koshland Professor in Jewish Culture and History at Stanford University, whose previous books include “Pogrom: Kishinev and the Tilt of History.” He first met Roth when he invited the author to speak to his colleagues and graduate students at Stanford. Roth showed up with a blonde woman in a silky blouse — not his wife at the time, actress Claire Bloom — and proceeded to spend the session flirting with her. His students were not amused.

They met again over the years under less antic circumstances and Roth gave his blessing to Zipperstein’s project. “We carried on a series of conversations, and he introduced me to his loyal entourage, and made it clear to them that they could share things with me that they otherwise might not have shared,” Zipperstein told me.

In our conversation, held over Zoom this week, Zipperstein and I spoke about how Roth scandalized the Jewish world with early works like “Goodbye, Columbus” and “Portnoy’s Complaint,” how he both resented and cherished his Jewish readers, and why so much of his prodigious output still holds up.

The interview was edited for length and clarity.

How did you come to write a biography of Philip Roth? He already had an authorized biographer, so what did you hope to bring to your book?

I’d met Roth years ago at Stanford — there’s a brief mention of it in the book. After I finished “Pogrom” there was this long pause before it came out [in 2018], and I started wondering what I might do next. I’d helped found the “Jewish Lives” series, and Roth seemed a pretty good fit.

But honestly, he’d been in my head long before that. I first read him in Partisan Review — a chapter from “Portnoy’s Complaint” called “Whacking Off” — just before I went off to the Chicago yeshiva. I was raised in an Orthodox family, wrestling with whether I could stay in that world. And Roth’s voice — it stuck with me. Not because of the masturbation, but because Portnoy has all this freedom and he’s miserable. That hit home. It told me that leaving the world I was raised in wasn’t going to be simple, and that freedom wouldn’t necessarily make me happy. That realization — about freedom and its discontents — has stayed with me my whole life as a historian.

Then, years later, I came across the recording of the Yeshiva University event in 1962 — the one Roth described as a kind of Spinoza-like excommunication. The tape told a completely different story. That was the moment I thought: there’s a book here, about the distance between Roth’s memory and reality.

Steven J. Zipperstein said his training as a historian helped him separate truth from fiction in writing his biography of Roth. (Yale University Press)

Let’s talk about that Yeshiva University event. Roth at the time was the young author of “Goodbye, Columbus,” which includes stories that some rabbis and others in the Jewish community said portrayed Jews in a negative light. Roth was invited to sit on a panel with Ralph Ellison and an Italian-American author to talk about “minority writers,” and Roth would later insist that the audience “hated” him. What did you find when you listened to the recording?

Well, Roth remembered it as this traumatic scene — the audience attacking him, shouting him down. But on the tape, the audience loves him! They’re laughing, applauding. The only confrontation comes from a few guys who come up to the stage afterward to argue.

What interested me wasn’t just that Roth misremembered it — it’s how he misremembered it. It tells you something about how he experienced the world. The people who criticize him are the ones who loom largest. That was revealing to me, both as a biographer and as someone who’s taught for decades. The people who dislike you — they’re the ones you remember.

But there is an almost literary bookend to that event: In 2014, the Jewish Theological Seminary awarded Roth an honorary doctorate. How did he react to that?

He was stunned! It was a casual decision by the institution, but a momentous decision as Philip saw it. He said in his speech, “This is the first time I’ve been applauded by Jews since my bar mitzvah.” He meant it sincerely.

Roth wasn’t a historian; he was a novelist. He remembered as he felt, not as it happened. My job was to separate those two things, not to punish him for it, but to understand the gap.

Roth once said, “The epithet ‘American Jewish writer’ has no meaning for me. If I’m not an American, I’m nothing.” As someone who insisted that he was first and foremost an American writer, as opposed to a Jewish writer, would he have liked being part of the *Jewish Lives” series?

Oh, I think so. He thought it was fair. We never talked about it directly, but I suspect he would’ve liked the company — King David, Solomon, Freud, Einstein.

There’s this anxiety about calling writers like Roth or [Saul] Bellow or [Bernard] Malamud “Jewish writers,” as though that makes them smaller. No one says Chekhov isn’t Russian enough. But say “Jewish writer” and people start to hedge.

I once said an American Jewish writer is someone who insists he’s not an American Jewish writer. Roth fit that perfectly.

There was a time when the Jewish experience was seen as a lens through which to understand modern life. Jews were central, not peripheral. Roth captured that paradox: Jews as both insiders and outsiders, too white and not white enough, privileged yet insecure. That ambivalence is his great theme.

“Portnoy’s Complaint” came out in 1969 and both delighted and scandalized readers with its descriptions of the narrator’s sexual adventures and fraught relationship with his Jewish parents. The reaction was extraordinary. I think it may be hard in our current era to imagine a literary novel selling so many copies and becoming such a part of the pop culture landscape.

[Critic] Adam Kirsch said it best — it was one of the last times a novel could set off the kind of cultural frenzy that today only Taylor Swift can provoke. The timing was perfect: Censorship had loosened, the sexual revolution was on, and “Portnoy” hit a nerve.

Roth claimed afterward that he didn’t want that kind of fame again. But of course he missed it. He hoped “Sabbath’s Theater” [his 1995 novel] would do it again. He knew it wouldn’t. He was mourning the loss of a serious readership, even as he kept writing as if it still existed.

Roth’s reputation seems tied up in how he portrayed women in his fiction and how he treated women in his personal life. You describe his serial relationships with many, many women, which often ended as soon as the sexual excitement wore off. At the same time, many of these same women remained loyal, and many gathered at his bedside as he lay dying, and some have written admiring memoirs. How did you approach that paradox?

I tried to be honest without being prurient. Roth decided very early that he was going to be a great writer — perhaps as great as Herman Melville or Kafka — and he came to conclude that there’s not a whole lot of discretionary time for relationships.

He’d fall in love hard, live with someone for two or three years, then move on. I didn’t moralize about it. Many of those women remained close to him. Others didn’t. He was loyal in his own way.

And his relationships with men, except for one significant detail, are not vastly dissimilar from those that he has with women. They’re utilitarian. Incredibly loyal friends hang on, because they’re so enamored by Roth and they feel deeply protective of Roth.

He also listened more intently than anyone I’ve ever met — though you were never sure whether it was you he was listening to, or the story he was going to write next.

Philip Roth receives an honorary doctorate at the Jewish Theological Seminary’s commencement in New York on May 22, 2014. (Ellen Dubin Photography)

Tell me about your book’s subtitle, “Stung By Life.”

It’s a phrase I found in a eulogy Roth wrote for his friend Richard Stern. He said Stern was “stung by life,” and I thought, that’s Roth.

He was perpetually shocked by existence — by what people do, by what happens to them, by what happens to him. Zuckerman, his alter ego, is defined by ambivalence — about women, about Jewishness, about America. Roth described everything well, but ambivalence best of all.

You’ve written books of history, and biographies of other Jewish literary figures, including the Zionist thinker Ahad Ha’am and Isaac Rosenfield, the American-Jewish writer who died in 1956 when he was only 38. What challenges did you find writing about a figure like Roth, who was still alive when you began work on the book, and what do you think you brought to it that maybe others couldn’t?

I’ve written and taught biography for years. Roth spent his entire life writing about himself, but not telling the truth about himself. That puzzle fascinated me.

Some Jewish figures — Isaiah Berlin, for example — chose biographers who didn’t quite understand the Jewish stuff. I wanted to do the opposite. I wanted to understand him from the inside out.

I loved his work before I started. I love it even more now. Words were my way out of a world where answers were predetermined by Maimonides. Roth fought that battle too —against dogma, against certainty, through language.

Sometimes I think Roth’s gifts as a comedian have overshadowed other qualities of his work — for example, everyone who read “Portnoy” remembers the slapstick about masturbation, but I love his lyrical descriptions of his old Weequahic neighborhood in Newark and heading down to the park to watch “the men” play softball. Was he worried that he’d be shelved in the “humor” section of the bookstore?

He liked to say he was a comic writer in the tradition of Kafka and [Heinrich] Heine — not Shecky Greene, [the Catskills comedian].

But yes, he could be incredibly funny. In many ways, “The Ghost Writer” [1979], as beautiful and lyrical as it is, is all written in order for Philip to have that punchline about Anne Frank.

The book’s narrator, Nathan Zuckerman, a writer like the young Roth, imagines that Anne has survived and that he can heal a rift with his family by bringing her home as his fianceé.

“Nathan, is she Jewish?” “Yes, she is!” “But who is she?” “Anne Frank.” In many ways, those were the lines that begat that brilliant book.

I also feel people overlook how much he wrestles with the Jewish condition — and not just Jewish mother jokes or nostalgia for the old Weequahic neighborhood. In books like “The Counterlife” and “Operation Shylock” Roth was writing about Zionism, assimilation, extremism and the tension between Israel and the diaspora when few other serious novelists were. Does he deserve to be more widely read as part of the very current Jewish debate over these topics?

Yes. I think in sort of more conservative, traditional Jewish quarters, he ended up being seen as an enemy of the Jews. But thinking about your question, it’s hard to think of any piece of extraordinary fiction that’s really made its way into the Jewish communal debate.

But Roth actually entered emphatically into the Jewish conversation. At one point in the late 1980s, Roth gives an interview to his friend Asher Milbauer. And he admits that the Jewish readership is his primary readership. He says writing as an American Jew is akin to writing for a small country where culture is paramount. As for other readers, he said, ”I have virtually no sense of my impact on the general audience.”

How would you describe that impact, and why should he still be read and admired?

Because he closes his eyes to nothing. He looks straight at the things we’d rather look away from — sex, aging, death, hypocrisy, joy. He writes about the child of good parents, the lover, the son, the dying man — all the selves we carry.

He shows how truth and illusion coexist, how clarity is always fragile. And he does it with language that’s alive. That’s what endures.

Does he still feel relevant to you?

Completely. Even among his contemporaries — [John] Updike, Bellow — Roth feels less dated. Maybe that’s because he was never comfortable. He kept interrogating everything, including himself.

That’s why he’s still with us. The rest of us are still trying to catch up.

Learn about Philip Roth’s “Portnoy’s Complaint” and other classics in a new course from My Jewish Learning: “Funny Story! The Best Jewish Humor Books of the Past 75 Years.” Taught by Andrew Silow-Carroll, the four-session course starts on Monday, Oct. 27 at 6 p.m. ET. Register here.

—

The post Philip Roth’s latest biographer wants Jews to read him again — without the guilt appeared first on Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

Uncategorized

Iran, Israel and Hitler’s gun are all on the ballot in key primaries in Texas and NC on Tuesday

(JTA) — With war in Iran breaking out just as two crucial states hold their primaries, a new PAC opposing pro-Israel spending will have its first big opportunity to flex its muscles among Democrats.

Meanwhile, a gun influencer with a penchant for Hitler jokes and Nazi symbols stands a chance to ride a scandal-ridden GOP primary all the way to Congress.

What unfolds Tuesday at the polls in North Carolina and Texas could reverberate throughout the midterms calendar as American Jews are facing unprecedented levels of political alienation from both sides of the aisle. Here’s what to watch for.

In North Carolina, Israel morphs from asset to liability

Pro-Israel election spending was already poised to be a hot topic this year even before the joint American and Israeli-led strikes in Iran reignited the issue of the Middle East. Nowhere is that more true than in North Carolina’s 4th Congressional District.

In the state’s densely populated Research Triangle region, incumbent Rep. Valerie Foushee has sworn off support from pro-Israel lobbying giant AIPAC — which spent more than $2 million for her in 2022. She has taken additional steps to distance herself from Israel, including refusing to attend Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s congressional address in 2024.

But her main opponent, Durham County Commissioner Nida Allam, is the one who is associated with criticism of Israel.

American Priorities PAC, which formed last month specifically to counter pro-Israel money, is spending more than $1 million in support of Allam, one of the major factors making the race one of the most expensive in state history. Allam also has the endorsement of Sen. Bernie Sanders and several leading progressive groups, while Foushee has the endorsement of the state’s centrist Jewish governor, Josh Stein.

In the homestretch, Allam’s campaign spending has focused almost entirely on tying Foushee to AIPAC, as well as to other groups like Article One PAC, which has a pro-Israel leading donor and has spent $600,000 supporting Foushee.

Both have criticized the Iran strikes in the campaign’s waning days, in different flavors. “I do not support Trump’s illegal war with Iran,” Foushee tweeted, without mentioning Israel. Allam, meanwhile, is homing in on Israel: She told Politico that district voters “are ready to hold every leader who co-signed a blank check to the Israeli war hawks accountable — including my opponent,” and said in a video message opposing the strikes, “I will never take a dime from defense contractors or the pro-Israel lobby.”

At the same time, Allam has taken on some outreach to local Jews; among other gestures, she recently read a resolution celebrating the safe return of Israeli hostage Keith Siegal, a native of her district.

Democratic Majority for Israel, a pro-Israel group focused on Democrats, has not issued an endorsement in the race. North Carolina’s Democratic party has recently been engulfed in an antisemitism scandal after the head of its Muslim caucus called Zionists “modern day Nazis” and a “threat to humaity.” Gov. Stein has denounced antisemitism in the party.

Another North Carolina Democratic candidate, Rep. Deborah Ross, has also sworn off accepting AIPAC money in her own re-election bid in the state’s 2nd district. Ross is not facing any primary challengers.

Jasmine Crockett’s anti-Israel pastor may have a big day

One of the most closely-watched races nationally will be the Texas Senate primaries, where Rep. Jasmine Crockett is in a dead heat against another rising Democratic star, state Rep. James Talarico. (Both candidates have signaled support for Israel as a Jewish and democratic state but have denounced the strikes in Iran.)

But whichever way their race goes, the figure coming up behind Crockett is a cause for concern among some supporters of Israel.

Frederick Haynes III, a prominent Baptist minister and Crockett’s own pastor, is running for her seat in the state’s heavily Democratic 30th district and is a clear favorite. Like Allam in North Carolina, Haynes is also a beneficiary of American Priorities PAC, with the anti-Israel group spending at least $72,000 to support him.

Long before announcing his candidacy, Haynes has bucked Democrats on Israel. The day after the Oct. 7, 2023, Hamas attacks in Israel, the pastor delivered a sermon drawing on former President Jimmy Carter to accuse Israel of “apartheid.”

“I recognize that we gotta be pro-Israel, yeah we got to do that, or we get in trouble,” he told his congregation in a snippet of a sermon posted to his Facebook page on Oct. 8. “Well, I’m coming to get in trouble.” He continued, “This country’s going to stand on the side of apartheid because that’s its track record.”

Throughout the war, Haynes would often seek to provide “context” for Oct. 7 or otherwise apply pressure to Israel, according to Jewish Insider. By January 2024 he was pushing then-President Joe Biden to cut off U.S. support for Israel if its war in Gaza continued. He has also disparaged Christian Zionism, in a similar manner to Tucker Carlson and other anti-Israel figures on the right. Prior to the attacks, he had been photographed with Nation of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan, calling the Black nationalist with a long history of antisemitism “a wonderful and great man.”

Haynes also opposed war with Iran in a tweet sent the day of the strikes, without mentioning Israel.

Haynes has dwarfed his Democratic opponents in fundraising in the Dallas-area district, recently redrawn by Republicans as part of a contentious mid-decade redistricting fight.

‘The AK Guy,’ who restaged Hitler’s suicide, could win in Texas

“The man who killed Hitler has got to be a personal hero of mine,” Brandon Herrera declared in a YouTube video posted last year — before an assistant of his told him, in a stagey whisper, that Hitler died by suicide. Herrera then gave his best “The Office” stare to the camera.

That joke is a distillation of the irony-laced, very online humor favored by Herrera, a far-right 30-year-old gun manufacturer and firearms influencer who goes by “The AK Guy” and who on Tuesday is challenging — for the second time — GOP Rep. Tony Gonzales for his Texas seat in Congress.

In Herrera’s 2025 video, titled “Testing The Gun That Killed Hitler,” he wields the firearm Hitler used to shoot himself while cracking jokes about Nazi salutes and conspiracy theories imagining Hitler’s survival in Argentina. It’s not the only time he has waded into such territory.

In 2022, reviewing a Nazi-manufactured submachine gun, Herrera joked that it was “the original ghetto blaster” and filmed himself goose-stepping with the weapon over the Nazi song “Erika.” (In the video, Herrera describes the song as “a bunch of soldiers singing about a pretty girl they miss at home” and says, “There’s absolutely nothing wrong with the song we just used.”)

Beyond Nazis, the Herrera-Gonzalez rematch is notable for several reasons. For one, the district includes Uvalde, site of the 2022 elementary school mass shooting, and Herrera has attacked Gonzales for a gun-control vote he made in the shooting’s aftermath.

For another, Gonzales’s career has become consumed by a lurid scandal in the days leading up to the primary, after a staffer he allegedly pressured into sex later died by suicide — vaulting the political neophyte Herrera into a strong position to unseat the incumbent, who has refused to step down.

AIPAC’s United Democracy PAC heavily boosted Gonzales while avoiding Israel as an issue during the duo’s first showdown in 2024, which ended in a runoff and a razor-thin Gonzales victory of around 400 votes in advance of his general election win.

Herrera, while saying that he “despise[s] AIPAC” over its spending against him, has also stated that Israel “is far from a top issue for me” and condemned Hamas the day after Oct. 7. “I’m not anti Israel, I’m anti Israel buying US elections,” he tweeted in 2024.

For his part, Herrera has also offered qualified support of military action in Iran, tweeting, “If there must be military action, let it be QUICK, effective, and please God keep our service members safe.” Gonzales, too, is supporting the strikes on Iran, tweeting, “Under President Trump’s close watch, the Iranian people have a historic opportunity to reclaim their country and embrace freedom.”

Another mass shooting in the state, this one with apparent links to Iran, may end up boosting Herrera’s bid as well. After a gunman in Austin outfitted with Iranian-flag clothing and wearing a “Property of Allah” sweatshirt killed three people including himself and injured 14 at a bar over the weekend, Herrera was one of many state Republicans who seized on the issue.

“‘Diversity is our greatest strength,’” the candidate tweeted mockingly, over a photo of the assailant, who was a naturalized American citizen from Senegal.

So where is AIPAC, really?

With an increasingly toxic brand, and facing backlash after a New Jersey primary campaign expenditure that backfired to likely help a pro-Palestinian candidate get elected, it might not be surprising if AIPAC kept a low profile this election cycle.

Then again, the group and its United Democracy Project have reported around $95 million, a massive war chest, and say they intend to spend intensively for the midterms.

AIPAC has made one, possibly consequential endorsement in a Tuesday race: GOP Rep. Wesley Hunt, who is running for senate in Texas. Hunt, however, is considered by most pollsters a third-place candidate in what has shaped up as a tight race between incumbent Sen. John Cornyn and Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton, each competing for the MAGA mantle.

Opposing PACs, meanwhile, are making a big show of pushing against pro-Israel money. In addition to American Priorities PAC, the Anti-Zionist America PAC, an upstart group whose founder tried to court white nationalist Nick Fuentes, is also backing a few candidates much more on the fringes of both parties.

Those include Texas Democratic hopeful Zeeshan Hafeez, who is running against incumbent Rep. Colin Allred in the state’s 33rd district and who has cross-endorsed with Haynes; and Republican Mark Newgent, who is challenging incumbent Rep. Keith Self in the state’s 3rd district.

The post Iran, Israel and Hitler’s gun are all on the ballot in key primaries in Texas and NC on Tuesday appeared first on The Forward.

Uncategorized

Death of Iranian leader just before Purim revives Book of Esther parallels

(JTA) — In Jewish time, history often has a way of rhyming with the calendar. So when Iran’s supreme leader Ali Khamenei was killed in an Israeli air strike on the Shabbat before Purim — the holiday that commemorates the downfall of Haman, a Persian tyrant who sought to annihilate the Jews — it was perhaps inevitable that rabbis, politicians and social media commentators would reach for the Book of Esther.

Some did so reverently, others triumphantly, and a few with a wink. But as Jews prepared to don costumes and drown out Haman’s name with noisemakers, the ancient story of survival in Persia collided with a very modern war in what is now known as Iran.

The Orthodox Union, the Modern Orthodox umbrella group, put out a statement titled “Purim in Our Time: Standing Up to Iranian Tyranny.” “We will read the Bible story of Esther and Mordecai overcoming the genocidal plans of Haman, who sought to destroy the Jewish people. Today, in coordination with Prime Minister Netanyahu and the IDF, President Trump and the U.S. armed forces took defensive action to silence a modern threat from the same ancestral land of Haman,” the statement read.

Such comparisons have proliferated since the killing of Khamenei.

In his first statement after the beginning of the war, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu made the connection to Purim explicit.

“Twenty-five hundred years ago, in ancient Persia, a tyrant rose against us with the very same goal, to utterly destroy our people,” Netanyahu said. “Today as well, on Purim, the lot has fallen, and in the end this evil regime will fall too.”

Known as Persia until 1935, Iran has been belligerent toward Israel at least since the Islamic Revolution of 1978-79, which brought clerics like Khamenei, with their frequent chant of “Death to Israel,” to power.

The holiday takes its cue from the Book of Esther, which describes how the Jewish queen to the Persian king Ahasuerus engineers the downfall of Haman, an advisor to the king who was plotting the murder of the kingdom’s Jews. Although Jewish tradition treats the book as historical — and Ahasuerus is often associated with the historical ruler Xerxes I — biblical scholars and historians tend to regard the story as what scholar Adele Berlin, author of “The JPS Bible Commentary: Esther,” called a “historical novella.”

Jews across the religious spectrum noted the comparison, often to different ends. Agudath Israel of America, the haredi Orthodox umbrella group, talked about prayer and salvation in its statement about the war.

“The upcoming Jewish holiday of Purim celebrates the downfall of those who rose up against the Jewish People in ancient Persia nearly 2,400 years ago,” it read (the events described in Esther are thought to have taken place in the fifth or fourth century BCE). “We are reminded how the key to the miraculous salvation was the heartfelt prayers of men, women, and children. While prayer is always powerful, our sages have taught that it carries special power during the Purim holiday season. We call upon the Jewish community to unite in prayer and beseech the Almighty to protect all those on the front lines and in harm’s way in Israel and across the Middle East.”

Rabbi Nicole Guzik, senior rabbi at Sinai Temple, a Conservative congregation in Los Angeles, spoke about human agency in her hastily rewritten Saturday sermon.

“Right now we stand at a critical stage where the story shifts, where the final paragraph in the Megillah that we are reading right now, in real time, has yet to be written,” she said, using the Hebrew name for a scroll like the Book of Esther. “The U.S., Israel, our beloved nations are holding the pen, and they are declaring, with courage and conviction, that we will be the authors of our future in the same manner as Esther.”

Some of the comparisons have been offhanded, even flippant. The novelist Dara Horn, speaking Sunday night at a forum on combating antisemitism at the 92nd Street Y in Manhattan, said, “Tomorrow night is Purim, and I think it’s clear to all of us now that the best way to fight antisemitism is to take out Haman with an F-15.”

Comedian Yohay Sponder, an Israeli who often performs in North America, posted a video of a routine commenting on the death of Khamenei. Like the Purim hamantaschen cookies named after Haman, he predicted a time when Jews will eat a food named after the slain Iranian leader. He suggested khamin, the Shabbat stew also known as cholent.

Others have already adapted hamantaschen for the moment. Some have joked about baking “Khamentaschen,” combining the new nemesis’ name with the treat named for an ancient one. At least one bakery in Israel produced “Ayatollah-taschens” with a chocolate center resembling Khamenei’s trademark turban.

Evangelical Christians and Messianic Jews, for whom the Esther story has had increasing significance in recent years, also seized on the parallels. “It all made an amazing story back then, and we are praying for an equally miraculous outcome in our days that will lead to the salvation of many in Israel, Iran, and throughout the whole Middle East,” the One For Israel Ministry, a U.S.-based Messianic group, posted on Facebook..

Meanwhile, some suggested that the timing of the attacks appeared to be more than a coincidence. Digital creator Evan Pickus noted in a Facebook post that, according to the Book of Esther, Haman was hanged on the gallows just days before the calendar date that became Purim. “The evil Persian Prime Minister [sic], who issued a promise to kill all the Jews, destroyed on the same day as his ancestor,” wrote Pickus. “I honestly believe our leaders planned it this way, and I love that.”

Although no Israeli or U.S. official has said they planned the attack with Purim in mind, the idea became a talking point over the weekend, especially after CNN posted a report by Israel correspondent Tal Shalev saying the comparisons had been widely shared in Israel.

Shalev also wrote of the significance of the attacks on the Iranian leaders’ compound falling on Shabbat Zachor, the “Sabbath of Remembrance” that precedes Purim on the Hebrew calendar. The day takes its name from a special Torah reading (Deuteronomy 25:17-19) commanding Jews never to forget how Amalek — said to be the ancestral nation of Haman — attacked the vulnerable Israelites after they left Egypt. The Israelites are given a somewhat contradictory command: “Blot out the memory of Amalek from under heaven. Do not forget!”

A widely circulated image from Beit Shemesh, where an Iranian missile killed nine people in a bomb shelter that also functioned as a synagogue, showed a fragment of shrapnel puncturing a Torah right on the passage that had been read a day earlier.

The injunctions about “Amalek” are often applied, sometimes controversially, as an ongoing commandment for Jews to show no mercy toward those who might eradicate them. That, in turn, has led some Israeli politicians and Jewish observers to cite Amalek in justifying Israel’s war on Hamas and Iran, and others to criticize those same politicians as ruthless and even genocidal.

Shalev’s report inspired at least some commentators to criticize Israel, suggesting the attacks were inspired by religious or nationalist fanaticism.

Purim is itself a strange mixture of the deadly serious and the wildly playful: a story of a thwarted genocide celebrated with carnival antics, including costumes, a raucous reading of the Book of Esther interrupted by noisemakers, and even a tradition of getting drunk. For millennia, it was often a release for a beleaguered minority in strange and often hostile lands. But as Israel emerged as a military power, scrutiny from within and without the Jewish community has often focused on the real-life implications of the story’s purported lessons.

Yet despite the Israeli politicians who take the Bible as a guidebook for revenge or Jewish supremacy, there is a long tradition of commentary that sees books like Esther as intentionally nuanced, even ambiguous guides to ethical behavior, including the prosecution of just wars.

Chapter 9 in the Book of Esther details the reversal of fortune for the Jews on the 13th of the Hebrew month of Adar, when they were said to have killed 75,000 foes in the wake of Haman’s downfall. Many Jewish commentators have expressed discomfort about what can be read as a heartless response to Haman’s thwarted decree.

On Sunday, Rabbi Michelle Dardashti expanded on that theme in a letter sent to members of her Kane Street Synagogue in Brooklyn. She warned that the Purim story is not just a celebration of the Jews’ victory over a Persian despot, but a warning that “battles that begin in moral clarity do not necessarily remain that way.”

“Purim pushes us to contend with the gray — to recognize how quickly roles can flip; how, on a dime, individuals and nations can shift from victim to aggressor, from righteous to morally compromised, or into categories that resist easy labels altogether,” wrote Dardashti, whose father left Iran as a young man. “Anyone who tells you with certainty that this war with Iran will unquestionably be good for the Jews and good for the world, that it will surely end well or end quickly — I would be wary of heeding that voice.

“And anyone who speaks with absolute certainty about it being entirely disastrous, unquestionably wrong — I would be wary of heeding that voice as well.”

Rabbi Simon Jacobson, a popular lecturer from the Chabad-Lubavitch Hasidic movement, discussed the parallels between the war and Purim in an installment of his video series, “MyLife: Chassidus Applied.” “The goal, of course, is to eradicate the enemy in every possible way, exactly as it happened in Persia, 2400 years ago in the story of Purim,” he said of the war.

But Jacobson also drew on two common themes not only of the Purim holiday but of much of Jewish tradition: salvation from an enemy, and the ultimate redemption of the Jews and humankind. He characterized the war in metaphysical terms, regretting “any type of bloodshed” but aspiring to “what happens afterwards: a stage, an era, a permanent era of Messianic, … total, solemn, permanent and sustainable peace for all people of this earth.”

For some congregations, the confluence of the war and the Purim holiday posed a challenge in tone — with rabbis asking how their communities might celebrate with bombs falling across the Middle East and Israelis taking cover in bomb shelters.

At B’nai Jeshurun, an independent synagogue on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, the clergy offered a schedule of observance and celebration to match the ambivalent mood. On Monday, a traditional fast day in honor of Esther marking “moments of danger and uncertainty,” they urged congregants to turn “their hearts toward prayer and summoning strength before stepping into the unknown.”

At sundown, they wrote in a letter to congregants, when the fast “gives way to celebration, in a world shaken by violence and instability, we anchor ourselves in Purim’s four mitzvot”: hearing the Book of Esther, sharing gifts with friends, giving charity and sharing a meal with friends or family.

“We cannot resolve the uncertainty of this moment,” wrote the B’nai Jeshurun clergy. “But we can choose how we meet it — with prayer, with generosity, and with one another.”

Yoni Rosensweig, a rabbi in Beit Shemesh, wrote in a Facebook post that many of the comparisons between the Purim story and the war on Iran miss crucial distinctions.

“Yes, Haman wanted to destroy us, and so did Khamenei — but Khamenei was the ruler of Iran. Haman was not the ruler — he was nothing more than a schemer. This is not just a technical difference, it’s fundamental,” Rosensweig wrote in an email to JTA. “Esther and Mordechai are trying to survive, that is all, They are trying to maintain the status quo in someone else’s kingdom.”

While the events in Persia inspired a holiday, he argued, “there is nothing long-lasting about the Jewish future in Persia which comes from the story.” By contrast, the current war has the potential to profoundly shape the Jewish future, no less than the Exodus from Egypt celebrated at Passover.

“It is about creating something new (we hope) in the Middle East. It is part of a regional war against powers that want to obliterate us. We aren’t looking to maintain the status quo,” wrote Rosensweig. “We are standing up for our right to live free, as a sovereign nation. Much like the Jews who left Egypt weren’t looking to maintain the status quo but rather to embark on a new path and start a new journey, so too we are doing with this war.”

The post Death of Iranian leader just before Purim revives Book of Esther parallels appeared first on The Forward.

Uncategorized

US urges Americans to ‘DEPART NOW’ from Israel and a dozen other Middle Eastern countries

(JTA) — The U.S. State Department urged American citizens on Monday afternoon to urgently depart from over a dozen Middle Eastern countries amid the escalating conflict in Iran.

The list includes Israel, which halted all commercial air travel when U.S. and Israeli forces jointly attacked Iran on Saturday.

“The @SecRubio @StateDept urges Americans to DEPART NOW from the countries below using available commercial transportation, due to serious safety risks,” wrote Mora Namdar, the State Department’s assistant secretary for consular affairs, in a post on X.

In addition to Israel, the countries listed in the advisory were Bahrain, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, the West Bank and Gaza, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria, United Arab Emirates and Yemen. Several of the countries have been targets of Iranian fire as the regime there has sought to widen the conflict in the Middle East.

While Namdar’s advisory urged Americans to “depart via commercial means,” there is currently no commercial air travel in or out of Israel. Israeli airlines El Al, Air Haifa and Israir announced plans to launch rescue flights to bring stranded Israelis abroad back home once authorities reopen Ben Gurion Airport, but it is not clear when that could happen. Some Israelis are making their way to Taba, Egypt, for passage into and out of Israel, but flights there are limited. Taba is about a 20-minute drive from Eilat, in southern Israel.

President Donald Trump warned on Monday that the largest U.S. strikes on Iran are yet to come.

The post US urges Americans to ‘DEPART NOW’ from Israel and a dozen other Middle Eastern countries appeared first on The Forward.