Uncategorized

Sarah Hurwitz wants Jews to stop apologizing and start learning

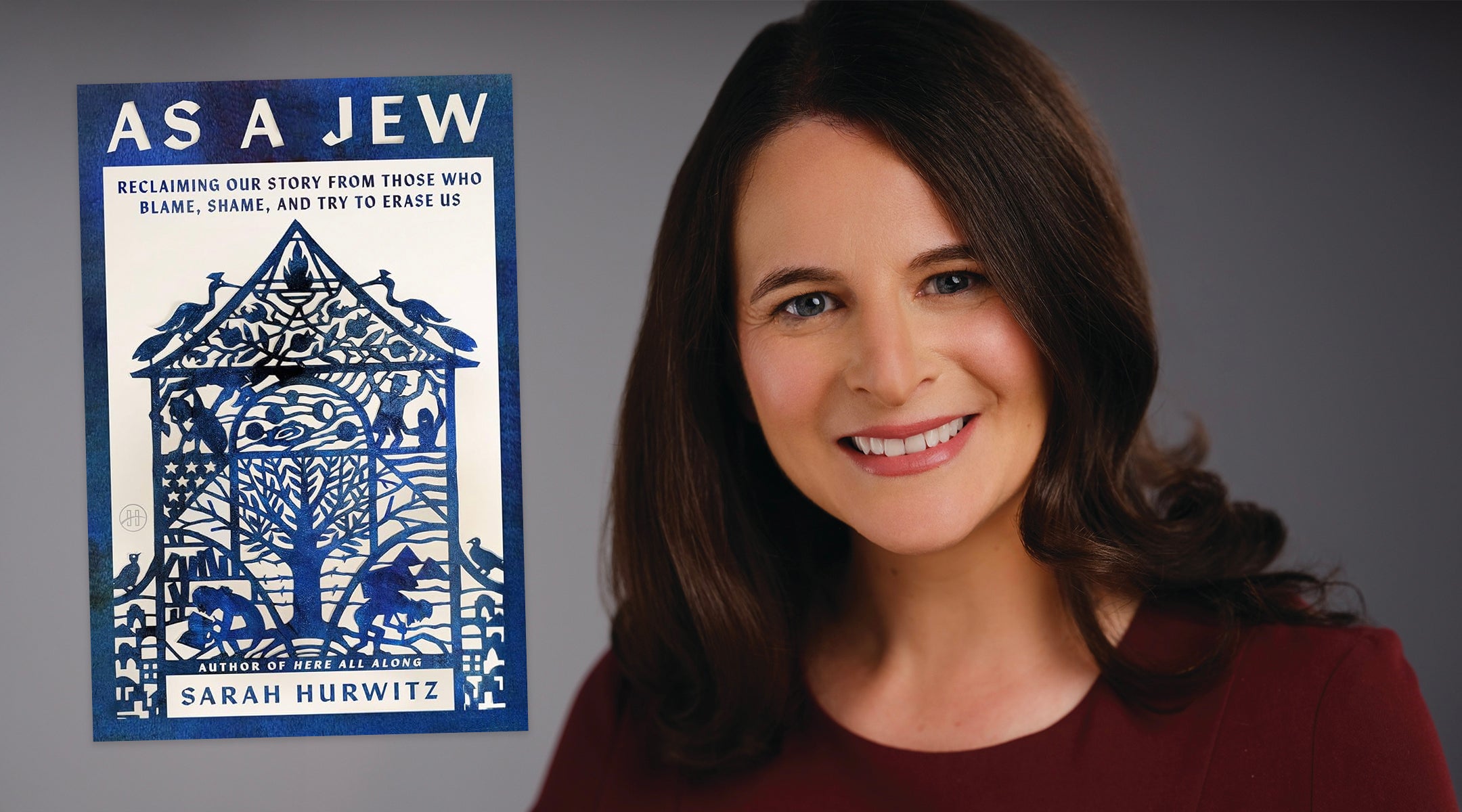

Sarah Hurwitz calls her first book, “Here All Along,” a “love letter” to Jewish tradition. Describing a journey begun when she worked as a speechwriter at the White House— first for President Barack Obama and later for First Lady Michele Obama — the book was a celebration of her rediscovering Judaism as a thirty-something who grew up with what she describes as a “thin” Jewish identity.

But if that book was sunny, her new book explores the shadows and storm clouds of Jewish belonging. “As a Jew: Reclaiming Our Story from Those Who Blame, Shame, and Try to Erase Us,” confronts the challenges of being Jewish at a time of rising antisemitism, a polarizing debate over Israel, and pressures and temptations that keep many Jews from appreciating a tradition that belongs to them.

Shifting the focus from personal discovery to a host of contemporary issues, “As a Jew” is both a primer and a polemic, explaining Jewish history, texts and practices in order to counter misinformation and inspire readers.

“We need to know our story. We need to know our history. We need to know our traditions,” she said in an interview on Thursday. “We need to know what we love about being Jews, so that when people come to us and they say, ‘Judaism is violent and vengeful and sexist and has a cruel God and is unspiritual,’ we can say that’s not true.”

The book also draws on her recent training and experience as a hospital chaplain, volunteering on the oncology floor of a hospital in the Washington, D.C. area, where she lives.

Hurwitz, 44, is a graduate of Harvard University and Harvard Law School. She also served as a speechwriter for Vice President Al Gore and in Hillary Clinton’s 2008 presidential campaign. In January, she plans to start training for the rabbinate at the Shalom Hartman Institute’s Beit Midrash for New North American Rabbis.

We spoke at a livestreamed “Folio” event presented by the New York Jewish Week and UJA-Federation of New York. Hurwitz discussed her time in the Obama White House, what she’s learned from meeting with college students struggling with antisemitism, and the challenges of writing a Jewish book in the post-Oct. 7 moment.

Our conversation was edited for length and clarity. To watch the full conversation, go here.

Your first book, “Here All Along,” was about your return to Jewish learning. What hadn’t you said in that first book that you felt compelled to say now? And how does “As a Jew” extend or challenge the earlier journey?

My first very much a love letter to Jewish tradition, and this book is much more of a polemic. That first book really reflected me at the age of 36 rediscovering Jewish tradition, having grown up with this very thin kind of Jewish identity.

In this new book, I began to really ask the question, why did I see so little of Jewish tradition growing up, why did I have to wait until age 36 to actually discover so much of our tradition? Why was my identity so apologetic, so kind of humiliating and, having grown up in a Christian country, how much of my approach to Judaism was really through a Christian lens? This book really dives into those questions at a time of rising antisemitism, where Jews need to start thinking about these things.

What does it mean to be apologetic? How did the Christian lens distort your understanding of Judaism?

I certainly believed that Christianity is a religion of love, but Judaism is really a religion of law. And I really did buy that, that ours is a kind of weedy, legalistic, nitpicky tradition with this angry, vengeful god. I mean, that is just classic Christian anti-Judaism. I also used to think this world is carnal, degraded, inferior, kind of gross, and the goal of spirituality was to transcend them. That is not a central Jewish idea at all. That is not what Jewish spirituality is. If you read the Torah, our core sacred text, you’re going to find a great deal about our bodies, but how we treat them, about really contemplating how they are quite sacred.

Sarah Hurwitz (left), a former speechwriter for First Lady Michelle Obama, does a “gazing exercise” with rabbinical student Lily Solochek at Romemu Yeshiva in New York, N.Y. on July 16, 2019. (Ben Sales)

You say more than once in your book that you want to “take back the Jewish story.” What does it mean to take back the Jewish story, and from whom or what?

Our story has often been told by others, and you actually see this in this very old story about Jewish power, depravity and conspiracy. You see it in the core story about a group of Jews conspiring to kill Jesus. And you see these themes winding their way through history. That story has been told about Jews for centuries. I want to replace it with our actual story, as told through Jewish texts and traditions.

The alternative you propose, in order for Jews to embrace their own story, is that they embrace the “textline,” which you call “the repository of our Jewish memory, the raw material for the story we tell about who we are.” I am not familiar with “textline” — how does it differ from “text”?

This is actually from [the late Israeli novelist] Amos Oz, and his daughter, historian Fania Oz-Salzberger. They say, “Ours is not a bloodline, it’s a textline.” Jews are racially and ethnically diverse, but our shared DNA, the thing that unites us, is our texts. Sadly, in the early 1800s, as Jews gained citizenship in Europe, there was a decision to assimilate and reshape Judaism to look more like Protestantism — a kind of “Jewish church.” In doing so, we de-emphasized 2,500 years of textual tradition beyond the Torah, which is where much of Jewish wisdom and ritual is found. Reclaiming that textual tradition is critical.

The idea and dilemmas of Jewish power is a theme in your book and incredibly timely, given the debate over Israel’s display of power in Gaza and several other fronts. How does your book approach the moral and spiritual tension of Jews moving from centuries of powerlessness to now having power and a state?

Many Jews today feel distress over the responsibility that comes with power. For 2,000 years, Jews were powerless, blameless victims. The problem with statelessness was that it led to slaughter on a massive scale. Some yearn for that innocence of powerless Jewish life, but I disagree that the cost of millions of deaths was worth it. With power comes moral responsibility. Israel, like all nations, is conceived and maintained in violence. I see the moral complexity, but I do not want to give up the power or the responsibility that comes with it.

After your first book came out, you became a prominent voice in Jewish life. Can you share encounters on the road that shaped your thinking for this book?

First, training as a volunteer hospital chaplain helped me realize the profound, Jewish-centered human experience of accompanying people in moments of illness, grief and death. Second, visiting universities before Oct. 7, 2023, I was stunned by Jewish students asking how I dealt with antisemitism in college. When I said I hadn’t experienced any, the students were shocked. Post-2023, the Gaza war accelerated ugly narratives on social media, which deeply worried me. I also reflected on my first book and realized that the Judaism I grew up with was oddly edited, shaped by our ancestors’ attempts to assimilate for safety — a choice I deeply respect but which left us somewhat “textless.”

How do your chaplaincy experiences relate text to real life?

I volunteer in D.C. hospitals. Being present with people in illness, grief and death is profoundly Jewish. Modern society finds these experiences uncomfortable, but Jewish tradition calls us to accompany mourners, prepare the dead lovingly, and inhabit the thin spaces where life and death blur. This presence, grounded in community, is essential. People often find relief simply in having someone acknowledge reality and speak openly about it.

You started writing this book before Oct. 7. How did the Hamas attacks and the Gaza war influence your writing about peoplehood, empathy and responsibility?

Oct. 7 didn’t change the arguments or themes of my book, but it gave more data points. For decades, Jews in America and Israel lived somewhat disconnected lives. Oct. 7 revealed underlying tensions and reminded us that Jewish identity has always carried conditionality. Some had illusions about a “golden age” of safety in the 1980s and 1990s, but many had faced real threats. The attacks shattered any illusions of security and exposed deeper societal challenges.

You talk about students on campuses being excluded from college clubs and causes because they are Zionist. I found your response intriguing — that Jews again create their own institutions the way they created Jewish hospitals and universities in the early part of the 20th century as a response to exclusion. Do you worry that you are overreacting?

Campuses vary widely. Some departments are excellent; some are hostile. In difficult environments, I advise Jewish students to try dialogue, but if excluded, to create their own spaces — clubs, organizations and initiatives, that are radically inclusive and excellent. Historically, Jews created hospitals, law firms and universities that welcomed anyone committed to excellence and tolerant of Jews. We can do that again. For example, Allison Tombros Korman founded the Red Tent after being ostracized [in the reproductive rights space] for her Zionist beliefs. It funds abortion services for anyone and is inclusive — an inspiring model.

Your book includes a chapter on Israel that aims to counter the accusations that Zionism is colonialist and racist. But you also include criticism of Israel, saying the country is not without its “serious flaws.” How do you navigate the lonely place of being a liberal Zionist today, which I often define as being too Zionist for the liberals and too liberal for many Zionists?

I navigate it like I navigate being an American: I can criticize, feel frustrated and yet remain committed. Israel is the home of 7 million Jewish siblings. Criticism does not mean abandonment. Many confuse ideology with family obligation, but Israel is our family, and we must stand with it while lovingly correcting its errors. This mirrors my commitment to America.

You were active in a Democratic administration and no doubt have seen the evidence of decreasing support for Israel among Democrats. Was that your experience when you worked in the Obama administration? Is that something you had to push back against?

I think people are a little bit confused about when the Obama administration ended, which was 2017. That was well before this 2023 dark turn, you know, it was a pretty normie administration. I don’t remember a single time in the Obama administration where anything negative was said about Israel. It was a great administration to be a Jew. I started first exploring Judaism when I was working in the White House, and my colleagues were so overwhelmingly proud of me, I could not just [believe] the encouragement they gave me. One time I actually ran into the White House chief of staff, a wonderful guy named Denis McDonough, and he asked me what I was doing for the December vacation, and the answer was, I was going to a weeklong silent Jewish meditation retreat. You don’t tell the chief of staff that you’re doing that, but I did, because I didn’t want to lie, and he just could not have been more proud.

Sarah Hurwitz interviewed by Norwegian actor Hans Olav Brenner in 2017, under a photo of her and President Barack Obama during her time as one of his speechwriters. (Thor Brødreskift/Nordiske Mediedager)

I now see, unfortunately, an ideology that’s been on the fringes of the left slowly making its way to the mainstream, and that worries me. I don’t think it is outrageous for Democrats to withhold an occasional shipment of weapons to express displeasure with Israel’s policy, but what worries me is that we are in a bigger environment of a real demonization and delegitimization of Israel.

I’m also really worried about the right. If you look at the data, especially among young men, they’re increasingly antisemitic, increasingly anti-Israel. And what I particularly worry about is that I see President Trump under the guise of fighting antisemitism on campus, engaging in really heavy-handed efforts to defund university campuses. And you can celebrate that. You can say it’s good for Jews, but I disagree, and I also worry about the precedent, that five or 10 years from now, when there is a president with a very different political ideology, who says that “Israel is a terrorist country, Zionism is a terrorist ideology, and I’m going to go and defund every campus that has an active Hillel, because Hillel is a Zionist entity.” We’ve paved that illiberal path, and it’s very easy for someone on the other side to walk down it.

I also really worry about, on the right, the MAGA ideology that says that a small group of powerful, depraved elites is conspiring to harm you and your family, to vaccinate you, to make your kids trans. It’s a very ugly ideology that is the very structure of antisemitism. The leap between elites and Jews is about a centimeter and Tucker Carlson’s made the leap. It’s got millions of followers. A lot of other people are making the leap.

Your books are, as you’ve said, love letters to Jewish tradition. But often observant Jews, here and in Israel, who are deeply steeped in Jewish text and practice, also embrace views that are illiberal and ultra-nationalist. How do you reconcile their embrace of the “textline,” and the illiberal positions they arrive at?

You are talking about the extremists, like [Bezalel Smotrich and Itamar Ben-Gvir, two far-right Israeli cabinet ministers]. I think they are being quite unfaithful to Jewish tradition. Judaism operates in polarities, holding opposing truths: love the stranger yet remember Amalek; humility and self-esteem; compassion with caution. Extremists claim only one pole, but both are essential. Jewish tradition demands wrestling with these tensions.

And yet those tensions are straining communal ties. How do Jews remain responsible for one another when there are such deep disagreements?

Judaism emphasizes the ethic of family. Even if family members espouse objectionable views, we engage them with tochecha — loving, private rebuke — to correct and guide them. Boundaries must exist for safety, but generally, we strive to keep people at the table, engage with them, and educate them.

A lot of Jewish authors are finding that it is difficult since Oct. 7 to promote their books, especially when they lean heavily into Jewish or Israeli content. How are you being received, having written a Jewish book in this time and place?

I only do events in Jewish institutions with a very small number of exceptions, so I haven’t been in any bookstores. I’m not really interested in going to bookstores. I want to go to places that have, frankly, good security and where it will be more than 20 people. I will say I’ve been surprised at how little pushback I’ve gotten to my book, because I thought this was a pretty edgy book. You know, I think my first book was pretty soft — like, “yay Judaism!” The second book is a polemic, and I was worried that I would get real pushback, real criticism, real anger. And yet, from the Jewish world, I’ve had Jewish leaders who are more on the right-wing side of the spectrum politically who like it, and leaders who are on the left-wing part of the spectrum who like it. They’ll tell me, “I see your compassion, and I see that you’re really wrestling with the other side, with those who disagree with you.”

Is there a Jewish text that you kind of live by, or that you really love, or just came across yesterday that really spoke to you this week or in this hour?

There’s so many, but I’ll take one. I’ll just simplify it. In [the Babylonian Talmud, Brachot 5b,] Rabbi A gets sick and then Rabbi B shows up and takes his hands and heals him. But then Rabbi B himself gets sick and Rabbi C shows up and takes Rabbi B’s hand and heals him. And the rabbis studying the story are very confused, because if Rabbi B, who was kind of known as a healer, could heal Rabbi A, then when he got sick himself, why didn’t he just cure himself? Why did he need Rabbi C to come and cure him?

And the answer that they offer is because “the prisoner cannot get himself out of prison.” I just think that’s a really beautiful story about the ways that we become trapped in our own anxiety, fear, anger, loneliness and really do need other people to come and take our hand and kind of pull us out. I thought about this a lot while writing my book. There’s about 80 people in my acknowledgements who read part or all of this book. And that was very important, because as a writer, I cannot get myself out of the prison of my own biases, my own ignorance, my own narrow views, and so many people reached out, took my hand and said, “What you’re writing is wrong,” or “that’s offensive,” or “you don’t know what you’re talking about.” And they said it very nicely. It was so important to me because I could actually step out and learn.

So I love that story. I think it illustrates something profound about what it means to be human.

—

The post Sarah Hurwitz wants Jews to stop apologizing and start learning appeared first on Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

Uncategorized

Important North Carolina Democrats Said Zionists Are Nazis — Many People Are Okay With It

Anderson Clayton, chair of the North Carolina Democratic Party, speaks after Democrat Josh Stein won the North Carolina governor’s race, in Raleigh, North Carolina, US, Nov. 5, 2024. Photo: REUTERS/Jonathan Drake

The North Carolina Democratic Party is at war with itself over Israel and antisemitism.

Earlier this month, I reported that leaders from the North Carolina Democratic Party’s (NCDP) Muslim Caucus had recently made hateful posts on social media. Elyas Mohammed, president of the caucus, described Zionists as “Nazis” and “a threat to humanity.”

Jibril Hough, first vice president of the same caucus, said “Zionism is a branch of racism/white supremacy and must be fought with the same intensity.” He described Zionists as the “worst of humanity.”

This month, Hough posted that Jeffrey Epstein could be alive and in hiding in Israel as part of a US/Israel conspiracy.

Now, two prominent North Carolina Democratic leaders have strongly condemned the statements by Muslim Caucus leaders.

Gov. Josh Stein told Jewish Insider (JI), “Antisemitic comments and conspiracy theories have no place anywhere, including in the North Carolina Democratic Party.”

Former Gov. and current Senatorial candidate Roy Cooper (D) told JI, “These reprehensible posts were an unacceptable expression of antisemitism and I condemn them in the strongest of terms.”

Stein and Cooper’s comments came promptly after many letters were sent by community members, including a powerful letter co-signed by the four local Jewish Federations directed to Gov. Stein and party officials. The Federations explained:

As Jews in North Carolina who support the existence of the State of Israel, and who represent broad cross-sections of our state’s Jewish population, we find this language hate-filled, insensitive, inflammatory, and threatening. It is incompatible with the standards of responsible civic leadership and it should disqualify any individual from holding a leadership role within a political party structure. Immediate corrective action is required.

The American Jewish Congress thanked Stein and Cooper for “making clear that antisemitism and conspiracy theories are unacceptable in the North Carolina Democratic Party.” The NCDP Jewish Caucus also thanked Stein and Cooper.

Mohammed and Hough responded by quickly doubling down on their statements, likely knowing that many in the party would support them.

Mohammed pinned (placed) his post calling Zionists “Nazis” to the top of his Facebook account.

Hough shared The Algemeiner column reporting his comments to social media, proudly quoting himself saying Zionists are the “worst of humanity.”

Rather than apologize, the Muslim Caucus issued a statement defending Mohammed, proclaiming, “We will not be silenced.” The NCDP Arab Caucus also re-posted a statement defending Mohammed.

Last week, the Jewish Democrats were asked on Facebook, “Do you accept Zionists?” Without answering directly, the Jewish Democrats of NCDP responded, “we accept everyone who treats human beings with dignity.” These comments were then promptly removed or hidden from public view.

Rev. Dr. Paul McAllister is chair of the NCDP’s Interfaith Caucus. The day after Stein and Cooper forcefully rejected Mohammed and Hough’s comments, McAllister posted a photo of himself on social media standing with Hough.

This comes as no surprise. McAllister is well known as a man who promotes hatred towards Israel. For example, McAllister endorsed and spoke on a panel, “The Genocide in Palestine,” which prominently featured Leila Khaled on the flyer. Khaled is a convicted hijacker and member of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, designated as a terrorist organization by the US government.

A small Jewish, anti-Israel subgroup of McAllister’s Interfaith Caucus posted on social media, “WE STAND IN SOLIDARITY WITH ELYAS MOHAMMED.”

This subgroup, or sub-caucus, calls itself Jewish Democrats of NCDP and is openly referred to by supporters as the “non-Zionist caucus.”

Many Democrats believe this non-Zionist group was created to confuse the public into believing that Jews in North Carolina do not support Israel. The confusion is real and likely widespread.

For example, in a recent social media post, a commenter expressed confusion trying to distinguish between the much larger NCDP Jewish Caucus — which represents broad Jewish interests and statewide constituencies — and the very small Jewish Democrats of NCDP, which is the anti-Zionist sub-caucus.

Jewish Democratic leaders across the state have told me they believe the NCDP is violating its own rules by essentially allowing two Jewish caucuses. The NCDP’s Plan of Organization clearly states, “The party will recognize a single auxiliary or caucus for any specific purpose.”

Democrats point out that, for example, there are not two African-American caucuses or two LGBTQ caucuses that are trying to push different viewpoints. Democrats emphasize this is another example of how state party leaders implicitly allow, or even encourage, targeting and demonization of Israel and Zionists.

Jeffrey Bierer is a current member of the Democratic Party’s State Executive Committee. Speaking for himself and not any organization, he told me, “At least four of us [Jewish Caucus members] paid dues to the Interfaith Caucus and we never received any confirmation or information back.”

Bierer also told me he paid separate dues to the Interfaith Caucus’ Jewish Democrats group with the same result.

Bierer said, “We were 100% friendly and respectful and said we would like to get involved. We didn’t get any response. Zero response.”

I reached out to the Jewish Caucus regarding this issue. They provided me a statement that began:

In an effort to bridge religious and political divides, a few of our members attempted to join the NCDP Interfaith Caucus. Initially their membership fees were accepted, then when those members inquired about the lack of regular communication and meeting times, their money was later returned.

It is evident that the North Carolina Democratic Party should investigate this potential discrimination against Jewish members and members who identify with Israel.

The Muslim Caucus is newly formed and currently in the review process seeking “final approval” by the NCDP. The Muslim Caucus is prominently displayed on the NCDP’s website featuring Elyas Mohammed under the heading, “OUR PEOPLE.”

According to the NCDP’s Plan of Organization, caucuses are not just advocacy groups — they are included in, and contribute to, significant decision making and planning within the party.

The document explains, “Caucuses shall be represented on the NCDP Executive Council, the NCDP State Legislative Policy Committee and the Platform and Resolutions Committee by the State President or designated representative and participate in strategic planning for the NCDP.”

I have contacted State Chair Anderson Clayton and First Vice Chair Jonah Garson twice over the past few weeks, sending them quotes, links, and screenshots regarding the comments from Muslim Caucus leaders. They have not responded. Unlike Stein and Cooper, Clayton and Garson have not publicly denounced the comments made by caucus leaders.

Antisemitism within the NCDP is a systemic problem that goes well beyond a few caucus leaders. The NCDP has been targeting Israel for years. For example, on Saturday, June 28, 2025 — during Shabbat — the party passed six anti-Israel resolutions. One of these resolutions even accused Israel of taking “Palestinian hostages.”

Clayton has appeared in smiling photographs with Mohammed and Jibril over the past few years. It is expected and normal that a chair of a state party stands with caucus leaders. But now that Mohammed and Jibril have clearly distinguished themselves as hateful and have targeted a large share of the Jewish Democrats in North Carolina who believe Israel has a right to exist, it is also expected that Clayton and Garson publicly denounce these hateful statements. They have not.

Their silence sends a message that Jewish members of the North Carolina Democratic Party, and all members who support Israel’s right to exist, are not valued or respected.

Rabbi Emeritus Fred Guttman of Temple Emanuel in Greensboro, who formerly served on the executive committee of the state’s Democratic Party, explained:

What has occurred demonizes Jewish supporters of Israel and increases the risk of violent acts against Jews in North Carolina. This is extremely serious…Those in leadership positions should continue to speak out clearly and condemn it…Leadership carries responsibility, and failure to address antisemitism undermines the safety and integrity of the community. We certainly do not need a repeat in North Carolina of tragedies such as Bondi Beach, Manchester, England, or the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh.

The North Carolina Democratic Party should take prompt action to unequivocally demonstrate that antisemitism, and discrimination against Jews and those who identify with Israel, will not be tolerated. Jewish safety — and equal treatment for all — depends on it.

Peter Reitzes writes about antisemitism in North Carolina and beyond.

Uncategorized

Berlin film festival fends off criticism after jury president Wim Wenders rebuffs calls to criticize Israel

(JTA) — BERLIN — The renowned Indian author Arundhati Roy has announced she will not attend Berlin’s annual international film festival over its jury’s refusal to comment on the war in Gaza.

Dozens of past and present participants in the Berlinale, meanwhile, are criticizing the festival for its “silence” on Gaza in an open letter published on Tuesday. They include Javier Bardem, Tilda Swinton, and Nan Goldin.

Both actions follow comments by the president of the festival’s jury, the renowned director Wim Wenders, appearing to argue that art should be apolitical.

“We have to stay out of politics because if we made movies that are dedicatedly political, we enter the field of politics, but we are the counterweight to politics,” Wenders said during the first press conference of the Berlinale on Thursday. “We have to do the work of people, not the work of politicians.”

Wenders was responding to a question from a journalist who accused the festival of showing solidarity with people in Iran and Ukraine, but not with Palestinians. The journalist asked the jury whether it supported a “selective treatment of human rights,” knowing that “the German government supports the genocide in Gaza and is the Berlinale’s main financial backer.”

Another jury member, the Polish film producer Ewa Puszczynska, said that it was “not fair” to ask the judges about government positions on the war in Gaza.

Following the comments, Roy, who has long criticized Israel’s conduct in Gaza, announced her withdrawal from the festival, calling the statement “unconscionable.”

“To hear them say that art should not be political is jaw-dropping,” Roy said. “It is a way of shutting down a conversation about a crime against humanity even as it unfolds before us in real time – when artists, writers and film-makers should be doing everything in their power to stop it.”

The controversy comes as the Berlinale opens in a tense climate vis-a-vis the war in Gaza. While the festival has long cultivated a reputation as one of the more overtly political major film festivals, Germany has maintained firm prohibitions on some forms of Israel criticism even as challenges to its conduct in Gaza have surged among many Germans and artists worldwide.

In 2024, the same year the festival invited and later disinvited members of the far-right party Alternative for Germany, the Berlinale filed criminal charges against an employee who posted an unapproved message about Gaza on its Instagram page.

Now, in defense of its jury, the festival issued a statement on Saturday saying that “artists are free to exercise their right of free speech in whatever way they choose.”

“Artists should not be expected to comment on all broader debates about a festival’s previous or current practices over which they have no control,” wrote festival director Tricia Tuttle. “Nor should they be expected to speak on every political issue raised to them unless they want to.”

Defending the artists and jury, Tuttle lamented that filmmakers increasingly “are expected to answer any question put to them. They are criticised if they do not answer. They are criticised if they answer and we do not like what they say. They are criticised if they cannot compress complex thoughts into a brief sound bite when a microphone is placed in front of them when they thought they were speaking about something else.”

Several films at the festival focus on the Israel-Palestinian conflict, some more directly than others. They include a recut version of “A Letter to David,” a documentary that premiered last year about an Israeli hostage in Gaza who has since been released.

Following a screening of her short film about a boy in Lebanon who lives against the backdrop of Israeli warplanes overhead, meanwhile, director Marie-Rose Osta told the audience that, in case they did not know where Lebanon is, it is “north of Palestine, which some of you may call Israel.”

Roy, in a statement issued by her publisher, said that art should in fact be political, and accused the jury of stifling discussion “about a crime against humanity.” She called the statements by the jury “outrageous.”

A film festival spokesperson told the Juedische Allgemeine, the German Jewish newspaper, that it regretted Roy’s decision, “as her presence would have enriched the festival discourse.” A 1989 film based on her screenplay, “In Which Annie Gives It Those Ones,” is showing in the festival’s classics section.

The post Berlin film festival fends off criticism after jury president Wim Wenders rebuffs calls to criticize Israel appeared first on The Forward.

Uncategorized

How to Respond When Your Friends Cite Hamas’ Casualty Numbers

The head of an anti-Hamas faction, Hussam Alastal, fires a weapon in the air as he is surrounded by masked gunmen, in an Israeli-held area in Khan Younis, in the southern Gaza Strip, in this screenshot taken from a video released Nov. 21, 2025. Photo: Hussam Alastal/via REUTERS

Not long ago, a very intelligent friend asked me a sincere question.

He wanted to know whether, as a Zionist, I was disturbed by what he took to be a settled fact: that Israel had “killed 300 people in a tent while trying to get one terrorist.”

He wasn’t hostile. He wasn’t chanting slogans. He was genuinely troubled and trying to reconcile that number with my support for Israel.

What shocked me was not the question itself, but the assumption behind it. He works with numbers for a living, yet it had not occurred to him to ask the most basic question: “Is that figure actually true, and who produced it?” He had simply absorbed it as unquestionable reality.

When I explained that such numbers almost always trace back to Hamas-run institutions in Gaza, laundered through media outlets and NGOs that treat them as neutral sources, it was clearly a new way of looking at the war for him.

The conversation revealed something I see on a much larger scale: people who would never trust Hamas with their bank account are trusting it with their moral judgment.

When I describe Hamas’ listed death toll in Gaza, I describe it as the “casualty-number war.” It’s not just about how many people have died. It’s about who is doing the counting, what they are counting, and how those numbers are deployed to turn a complicated war into a morality play with ready-made villains and victims.

Hamas understands this perfectly. Its “Ministry of Health” in Gaza is not some independent public health office. It is part of a totalitarian structure that answers to the same regime that launched the October 7 massacre, embeds fighters and rocket launchers among civilians, and openly celebrates “martyrdom.”

Yet Western media outlets, NGOs, and politicians routinely preface their coverage with the same passive formulation: “According to the Gaza Health Ministry, more than X thousand people have been killed…”

Once that sentence is accepted as neutral, the argument is already half lost.

These headline numbers blur together every possible category of death: combatants and non-combatants, people killed by Hamas’ own rockets or internal violence, people who died of illness or old age, and people whose deaths are simply unverifiable.

There is rarely a breakdown by cause, location, or affiliation. The message is not “here is our best attempt at a complex casualty record.” The message is, “Israel killed this many people; now explain yourself.”

Western institutions, meanwhile, have powerful incentives to accept this framing. Journalists on deadline want a single, authoritative-sounding figure. NGOs need dramatic numbers to drive fundraising and campaigns. Politicians want an easy way to signal moral outrage without learning the underlying details. “According to Gaza’s Health Ministry…” gives them all exactly what they want.

The result is that Hamas’ tally becomes something close to sacred. To question it is treated as denial of suffering, rather than as basic due diligence.

To be clear, this does not mean that the real toll of the war is small, or that civilian deaths are imaginary. They are not. Wars in dense urban environments, against enemies who hide behind civilians, are always tragic. But tragedy does not excuse deception, and compassion does not require us to outsource moral judgment to a terrorist organization.

There is another trap we must avoid, however, and it lies on “our” side of the argument.

Recently, a claim circulated online that Hamas had “admitted” to losing 50,000 fighters and was preparing to pay stipends to their widows. It was an appealing narrative: if true, it would imply that the majority of Gaza’s war dead were Hamas’ own armed operatives, not civilians. Many people repeated it enthusiastically.

The problem is that the underlying evidence does not support such certainty. The 50,000 figure appears to come from extrapolations about an aid program for widows and vague statements in local media, not from a clear, formal admission of combatant deaths by Hamas itself. Israel’s own estimates of Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad fighters killed are much lower — on the order of tens of thousands, but not double that.

In other words, some of Hamas’ critics were tempted to do what they rightly accuse Hamas of doing: leaping from suggestive data to definitive, emotionally satisfying numbers.

That may feel good in the moment, but it ultimately weakens our case. If we want the world to take casualty manipulation seriously, we have to hold ourselves to a higher standard than Hamas does.

So how should we think and talk about Gaza casualty numbers?

First, always ask who is counting. A figure produced by a Hamas-run bureaucracy and laundered through sympathetic NGOs is not equivalent to an independent forensic assessment. That does not mean every number is automatically false; it means we must treat it as a political artifact, not a neutral statistic.

Second, ask what is being counted. Are natural deaths and pre-existing illnesses being folded into “war fatalities”? Are internal killings, executions of “collaborators,” gang violence, and misfired rockets landing in Gaza all being quietly attributed to Israel?

Are combatants and non-combatants being distinguished, or are they all being described as “civilians,” “women,” and “children”? If those questions are not being asked, the headline number is not serious.

Third, examine the incentives. Hamas gains strategically every time the West believes that almost every death in Gaza is an innocent civilian killed by the Israel Defense Forces. That perception fuels accusations of “genocide,” drives diplomatic pressure, and legitimizes further violence under the banner of “resistance.”

Conversely, Hamas has every incentive to hide its own fighters among civilians, both physically and statistically.

Fourth, be honest about uncertainty. We will probably never know the exact distribution of deaths in Gaza by category. That is the nature of war, especially in closed, authoritarian environments. But we can say, with confidence, that the picture is far more complex than the nightly news suggests.

We know that a significant share of the dead are combatants. We know that some deaths are caused by Hamas’ own actions, whether through misfires or internal violence. We know that some reported “war casualties” would have occurred from natural causes even in peacetime. A morally serious discourse must reflect that complexity.

For ordinary readers and viewers, the question becomes: what can I actually do when confronted with someone like my friend, who has been told that Israel “killed 300 people in a tent to get one terrorist” and accepted it as unquestionable fact?

A few simple moves can help:

- Slow the conversation down. Instead of arguing about whether 300 is “too many,” start with “Who gave you that number?” That alone often changes the entire frame.

- Separate grief from propaganda. It is possible to say, “Every innocent life lost is a tragedy,” while also saying, “That does not mean Hamas’ numbers are accurate, or that Israel is committing the crimes you’ve been told about.”

- Insist on categories, not just totals. Ask whether the figure distinguishes between terrorists and non-terrorists, between people killed by Hamas and those killed by Israel, between battlefield fatalities and natural deaths. Most numbers in circulation do not.

- Refuse to play by Hamas’ rules. Do not feel compelled to accept a Hamas-run institution’s tally as the starting point for every moral conversation. We are not obligated to let Israel’s enemies define the terms of debate, whether in language or in arithmetic.

My friend and I ended our conversation on good terms. He did not walk away with a perfect spreadsheet of Gaza casualties — neither of us has one. But he did walk away with a new question lodged in his mind: “Why am I letting Hamas tell me what to think?”

That, ultimately, is the goal. If we care about truth, about Israel’s legitimacy, and about the real human beings — Jews and Arabs alike — whose lives are at stake, we cannot allow a terrorist organization to be the world’s official statistician. We do not have to accept a calculator held in the same hands that fired the rockets and sent the “martyrs.”

We can insist on something better: honest categories, transparent methods, and a refusal to surrender our moral judgment to those who openly seek our destruction.

David E. Firester, Ph.D., is the Founder and CEO of TRAC Intelligence, LLC, and the author of Failure to Adapt: How Strategic Blindness Undermines Intelligence, Warfare, and Perception (2025).