Uncategorized

Two years after Oct. 7 shattered them, Israel’s border kibbutzim are drawing new dreamers

(JTA) — Two years after the Oct. 7 massacre, Israelis are moving into kibbutzim in numbers not seen for years, part of a deliberate effort to repopulate and rehabilitate communities devastated in the Hamas-led attack. The push is most visible along the Gaza border, but it extends to the north as well, where Hezbollah fire kept communities thinly populated for more than a year and a half.

Leaders of the movement speak of kibbutzim as the country’s living perimeter. Neri Shotan, who runs the Kibbutz Movement’s rehabilitation fund, invoked an old adage: If the country went dark and only kibbutzim stayed lit, their lights would trace the map of Israel. Roughly 100 of about 260 Israeli kibbutzim sit on the borders, a design Shotan said was meant to anchor the edges through civilian life rather than fortifications.

The scale of the damage remains stark. The movement counts 56 kibbutzim evacuated after Oct. 7 and says kibbutz communities lost 318 people in the attacks, close to a quarter of the roughly 1,200 killed that day. Some 40,000 kibbutz members were displaced.

A new wall listing more than 450 kibbutz members who died on Oct. 7 and in the subsequent Gaza war has been added to a longstanding memorial for kibbutzniks killed in acts of terror since Israel’s earliest days.

The state’s five-year plan for the Gaza periphery totals 19 billion shekels (US $5.75 billion) and a report released in September by the government’s Tekuma directorate, the agency tasked with rehabilitating the Gaza envelope, said 7.9 billion shekels had been allocated so far, including 525 million shekels this year for programs to encourage evacuated residents to return.

Around 90 percent of evacuated Gaza-border residents are back, according to the report, and more than 2,500 newcomers have moved into the region. Minister Zeev Elkin, who is overseeing the recovery, said the plan was to double the population to 120,000 in the coming years.

Yet some of the hardest-hit places are lagging. Only about a third of Nahal Oz’s residents have returned. Nir Oz and Be’eri are only now entering the rebuilding phase.

The reopening of the bakery and print shop at Be’eri, where more than 100 residents were killed and dozens were taken hostage, were hailed as major steps toward rebuilding. But many of the workers commute from a kibbutz 40 kilometers to the east, near Beersheba, where Be’eri’s displaced residents relocated.

And a ceremony to mark rebuilding at Nir Oz that featured Gadi Mozes, the octogenarian released from Hamas captivity in January who for many embodies the classic kibbutznik spirit, took place only in August, with workers placing the foundation then for new structures.

The Kibbutz Movement Rehabilitation Fund — set up within hours of the attack — positioned itself to fill gaps Shotan says the state has failed to address. It has raised roughly 160 million shekels to date, mostly from overseas donors.

Starting at 6 p.m. on Oct. 7, 2023, volunteers were handing out shoes to children who had fled barefoot, pressing the Interior Ministry to reissue identity cards lost in the wreckage and coordinating permissions and logistics for burials. In the months that followed, the fund placed evacuated children in schools, arranged ad hoc farm labour when reservist call-ups emptied crews and secured temporary housing. During June’s war with Iran, it set up an emergency volunteer hub that, among other tasks, delivered truckloads of mattresses to kibbutz shelters in the north.

The fund’s newest push is aimed at recruiting newcomers, in a project known as Chalutzi — a derivative of the Hebrew word for pioneer. Chalutzi serves as a clearinghouse and matchmaker between kibbutzim seeking members and newcomers looking for a place to live and volunteer. The project’s target is to relocate 1,000 families, with thousands of inquiries logged, alongside placements for young singles who want to live and work in border communities.

Among them is 29-year-old Ilan Gritsevsky, who in August left Tel Aviv for Kibbutz Nir Oz, where roughly a quarter of residents were murdered or taken hostage on Oct. 7 and where only six houses emerged unscathed. He is part of a cohort of about 50 young adults connected to the Hashomer Hatzair youth movement who are moving in as construction starts. For now they live in temporary housing financed by partners that include the rehabilitation fund, with new homes being built.

City life, Gritsevsky said, while fun, felt anonymous: “The only thing you share with your neighbours is a postal code.” The kibbutz offered shared purpose and a sense that neighbours were partners in rebuilding. But the deeper impulse, he said, was defense by presence. Called up on Oct. 7 to reserve duty in Nahal Oz, he described his relocation to Nir Oz as the natural next stage of service.

“At the beginning of the war I had to protect our borders with weapons, and today I feel that settling on our borders is a meaningful form of protection, for the country’s physical border and for the kind of country we want to be,” he said.

The new crop of young adults will establish an educational community, taking on informal education roles alongside the school day. The need is acute. Since Oct. 7, problems that were once uncommon among kibbutz teenagers, including substance and alcohol use, have become more visible, alongside broader trauma. Tekuma has earmarked 115 million shekels for personal, family and social services programs and 61 million shekels for trauma and bereavement, funding family-support services, parent-child centers, targeted assistance for at-risk families, prevention of domestic violence, treatment units for sexual assault, and programs for children, older adults and people with disabilities.

In April, Nir Oz reached a state agreement for 350 million shekels to rehabilitate the community – becoming the last of the Oct. 7–affected sites to do so – but according to Shotan, it falls short of the 500 million shekels residents say is needed. KKL-JNF, which is financing rehabilitation projects nationwide, approved 75 million shekels for Nir Oz as part of a 750 million shekel national package, helping to narrow the gap.

Shotan said selling the idea of kibbutz life to families and young people is not difficult, because education, community and social support are big draws, and the cost of living in the periphery is far less than in Israel’s population centers.

But ideology, he said, was doing most of the work in driving people to move. “You have to be a real Zionist to do it. People who don’t have Zionism as a basic value won’t come.”

He traced the idea back to the first kibbutzniks of the 1910s and to families like his, whose grandparents in the 1920s helped found Shefayim — the central Israeli kibbutz that housed evacuees from Kfar Aza after Oct. 7.

The same logic, he said, held on Oct. 7. In his telling, front-line communities have again become a part of Israel’s defense.

“The kibbutzes were relevant then and they’ll become even more relevant in the future. Our defense rests with them, not through the army. If it wasn’t for Nirim, or Nir Oz, Hamas terrorists would have reached Tel Aviv.”

But not all newcomers framed their move as classic Zionism. Maya, a founder of Torenu (“Our Turn”), a grassroots movement under the Dror-Israel youth movement, helped dozens of young people move to Gaza-border kibbutzim to staff classrooms, youth clubs and fields.

“We didn’t come to save anyone, and I don’t like the word ‘rehabilitate.’ We work alongside the people who were here long before us and who will probably be here after us,” the Kfar Saba native told the Hebrew-language Israel Hayom daily. “Some may call it Zionism, but that is not what guided me. I just felt more people were needed here to help get the wheels turning again.”

Maya gave up a job at a Tel Aviv startup to relocate to Kibbutz Re’im, along with eight other young adults. The community is back to over 180 families (out of 200 pre-war), and a further 10 new families have since joined.

The kibbutz’s secretary, Zohar Livneh-Mizrahi, said the new arrivals had changed the mood.

“It isn’t something to take for granted, but I see how strongly people want to be involved and lend a hand,” she said. “It moved me from the get-go, and still does. We are writing a new chapter in the history of the kibbutz and of Zionism.”

Repopulation of the northern kibbutzim is the Chalutzi project’s next frontier, Shotan said. Damage there is extensive, and the return has been patchier, with 30 percent of the kibbutz members still living elsewhere.

Israeli authorities put northern property losses at about 9 billion shekels, but only about 2.2 billion shekels had been disbursed by mid-year, leaving a large gap that locals say is slowing work on housing, public buildings and farms. Tenufa, the northern framework intended as a counterpart to Tekumah, lacked sufficient funds and authority to push projects, and kibbutz leaders say they have to work across more than a dozen ministries to secure approvals.

Agriculture could take four to five years to regrow, yet without permits in place, little has started. Some of the kibbutzes have grown tired of waiting. At Yiftach, where rockets destroyed about 90 percent of fields, kibbutz members chose to bypass the state and funded clearing and replanting on their own.

External shocks have compounded the strain, Shotan said. Houthi attacks in the Red Sea have disrupted shipping and forced longer routes, raising costs and in some cases, spoiling the exports. Economic boycotts levied at Israel have cut demand in certain European markets and new tariffs by the Trump administration have further scrambled trade flows and pricing.

Back south in Nir Oz, Gritsevsky joined 200 others for a communal Rosh Hashanah meal. He described the mood among the new arrivals and veterans as a mix of resolve and strain.

“We’re all still living with this tension that on the one hand, it isn’t over – the grief is still with us and will keep being with us, but at the same time, we want to stand up and take responsibility to rebuild,” he said.

The post Two years after Oct. 7 shattered them, Israel’s border kibbutzim are drawing new dreamers appeared first on The Canadian Jewish News.

Uncategorized

Bari Weiss, Free Press founder who started as antisemitism crusader, named editor-in-chief of CBS

Bari Weiss, the journalist who first rose to prominence for her campus campaign alleging antisemitism two decades ago, has been named editor-in-chief of CBS News, a stunning ascent that marks one of the most consequential appointments in American media in recent years.

The appointment came as Paramount Skydance, led by David Ellison, announced its $150 million purchase of The Free Press, the publication Weiss founded in 2022. Weiss will oversee both outlets as editor-in-chief, reporting directly to Ellison. The move marks a major shakeup for a legacy news division long associated with mainstream liberalism and a bet on Weiss’s brand of provocative centrism.

Ellison’s involvement adds another layer of intrigue. The son of Larry Ellison, the Oracle founder known for his pro-Israel philanthropy, David has in recent months gained attention as his father helped spearhead a bid to acquire TikTok’s U.S. operations. The forced sale, mandated by a new U.S. law aimed at separating the platform from its Chinese ownership, has drawn political scrutiny and elevated the Ellisons’ influence at the intersection of media, tech, and geopolitics.

For Jewish observers, Weiss’s trajectory carries special resonance. Her public identity has long intertwined with Jewish causes, Israel advocacy and debates over antisemitism and free speech. Under her leadership, The Free Press has become a prominent voice on the American Jewish experience, particularly its coverage and commentary supporting Israel and condemning rising anti-Israel activism after Hamas’ Oct. 7, 2023, attack on southern Israel.

Born in Pittsburgh and educated at Columbia University, Weiss first emerged as a student activist in the early 2000s when she campaigned against professors she accused of anti-Israel bias, a battle that foreshadowed later campus wars over Zionism and academic freedom. A film she co-produced called “Columbia Unbecoming” documents her account.

Raised in a Reform Jewish household in the Squirrel Hill neighborhood, her connection to the community became national news with the 2018 shooting at the Tree of Life synagogue, the congregation where she had her bat mitzvah. The massacre, she wrote, was an “alarm bell” that shook her out of a “holiday from history.” She channeled the tragedy into a book, “How to Fight Anti-Semitism,” in 2019.

Now 41, Weiss has positioned herself as a defender of open inquiry within liberal institutions and a critic of what she saw as left-wing intolerance. She rose through the editorial ranks at The Wall Street Journal and The New York Times, where she became known for her critiques of “cancel culture.” Her 2020 resignation letter from the Times, alleging bullying and ideological conformity, went viral and turned her into a hero for many self-described centrists.

When she launched The Free Press, Weiss promised to create a home for “free thought and fearless reporting.” The site quickly grew into a digital media powerhouse, attracting major investors and millions of readers, but also attracting criticism from those who say Weiss’s project is a polished rebranding of right-wing media.

Now she will have the chance to bring her brand of journalism to a much broader audience, as the top editor overseeing coverage at a legacy news organization whose properties include “60 Minutes” and “Sunday Morning.”

“As proud as we are of the 1.5 million subscribers who have joined under the banner of The Free Press — and we are astonished at that number — this is a country with 340 million people. We want our work to reach more of them, as quickly as possible,” Weiss wrote in a letter to readers on Monday. “This once-in-a-lifetime opportunity allows us to do that.”

—

The post Bari Weiss, Free Press founder who started as antisemitism crusader, named editor-in-chief of CBS appeared first on Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

Uncategorized

In my small town, ‘that Jewish hut’ has turned Sukkot into a cross-cultural shelter of peace

On the weekend between Yom Kippur and Sukkot, Waterville city workers put up the frame for our community sukkah. They were careful to make sure that tree branches did not obscure the view of the stars and the night sky, and that sufficient room was left for a Wabanaki storytelling festival in the town square scheduled during the same week.

This was the second year our municipal workers erected “that Jewish hut.” I never thought Waterville would support the Jewish community in building, hosting, and supporting our sukkah; it came about through an unexpected and somewhat painful discussion. For years, Waterville has hosted “Kringleville,” a community celebration of Santa Claus and Christmas. A non-Jewish member of the Waterville community challenged the practice, and demanded a menorah be placed next to the Christmas tree. Some community members supported this move; others wanted all public observances of religious festivals to end.

Our synagogue leadership was ambivalent about either option. I’ve never liked the idea of Hanukkah competing with Christmas, elevating a minor festival not because of its importance, but rather because of its proximity to a major holiday outside of our tradition. I also believe we should retain community events — religious or otherwise — that reinforce faith, community, and good will. I don’t believe that diminishing Christian festivals strengthens the Jewish community. In light of these values, we suggested a different path forward for the City of Waterville.

In a meeting with the city manager, our synagogue’s executive director, Melanie Weiss, suggested that rather than erect a menorah in the winter, we erect a sukkah in the fall. Why? Sukkot is a major Jewish festival in its own right, the city could provide support for our small synagogue that we actually needed and wanted (putting up a sukkah is hard work!), and we could leverage central Maine’s agricultural and multi-ethnic traditions to bring joy not only to the Jewish community, but to everyone in our region.

Sukkot is a festival about hospitality, joy and creative construction. In the wake of Oct. 7, our synagogue staff and board believed that inviting the greater community into our spaces was a better approach than pulling away behind walls. We wanted our public face to be welcoming, inclusive, beautiful, and proud. As such, in partnership with the Center for Small Town Jewish Life at Colby College, Waterville Creates (our local arts organization), Beth Israel Congregation, and the Waterville Public Schools, we spearheaded a citywide arts project so that everyone in town could contribute some kind of personal decoration to adorn our community sukkah.

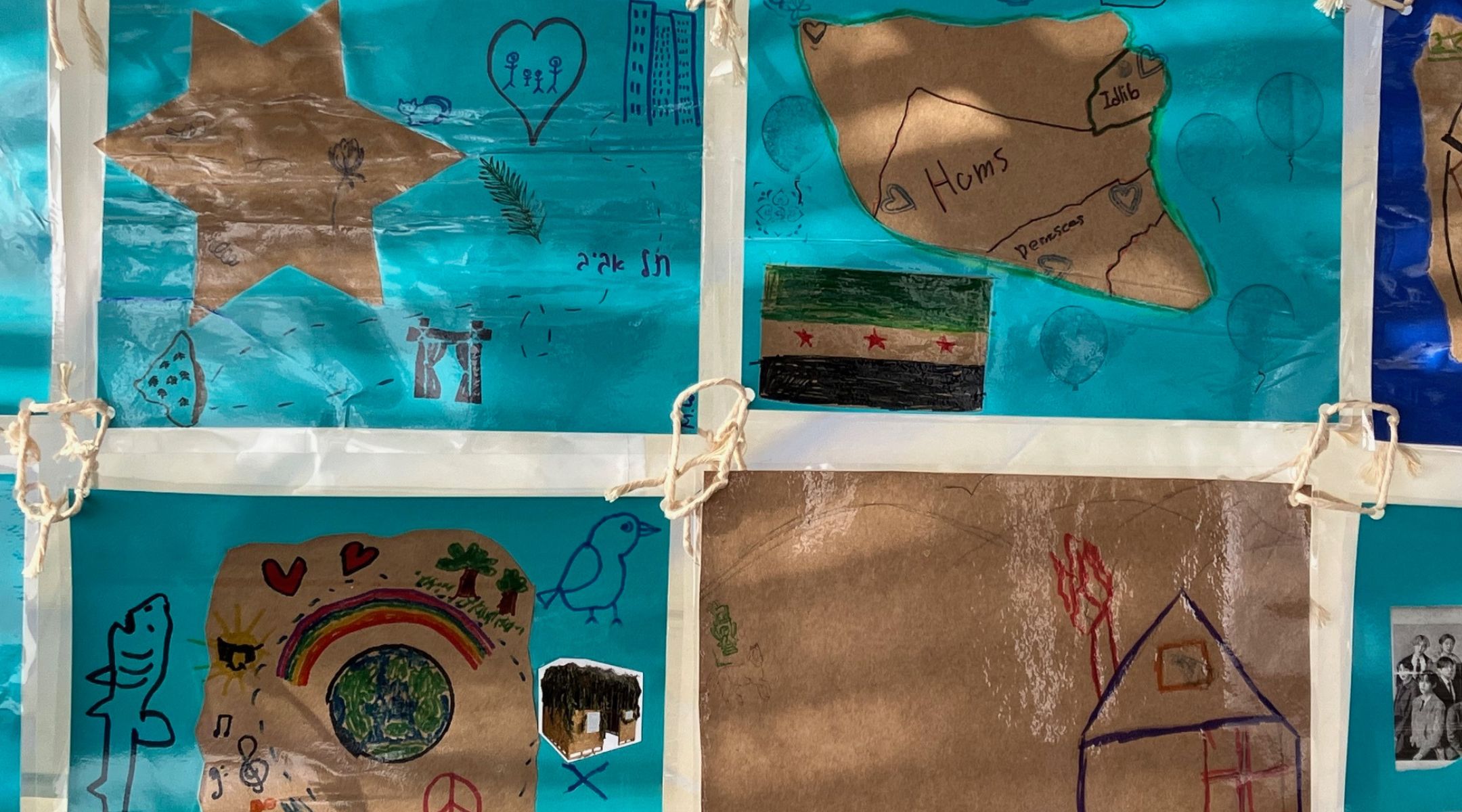

In our first year, we organized an art project around “Welcoming our Ancestors,” teaching the greater community about ushpizin and providing a canvas for our neighbors to highlight their journeys from Lebanon, Quebec, Congo, Syria, Iraq, Lithuania and yes, Israel. This year (our second), our community art project charges participants to craft a “Map of Joy” depicting their personal journeys from origin points around the world to places of joyousness. Panels depicting heartfelt and arduous journeys from Homs, Syria, sit next to panels that highlight the vibrancy of Tel Aviv.

This year’s art project asked participates to create panels depicting personal journeys from places around the world. (Courtesy Center for Small Town Jewish Life)

On Erev Sukkot, we host a vegetarian potluck dinner with dishes from around the world, and we share the blessings of Sukkot with our neighbors. Before candle lighting, we show participants the lulav and etrog, and later we explain the story of Sukkot and its core values. In coordination with Waterville Adult Education and the Capital Area New Mainers Project, we invite translators to make our teaching accessible, and have printed materials in several languages that are spoken in local immigrant communities.

This project isn’t without its detractors. Some resent or oppose Jewish content and representation in public spaces, even if it is in equal measure to Christian, Muslim and Indigenous traditions. Some have asserted that our multifaith work is a way to evade discussions of Israel and Gaza Others fear that the sukkah will be desecrated or attacked. In essence, most of the opposition comes from antisemitic sentiment or the fear of it. And yet we have chosen to put up our sukkah with the support of city partners and with the vigilant protection of the Waterville Police Department. We refuse to acquiesce to the suspicion and hatred of others, or to the fear that it will be expressed.

The Waterville Jewish community and the Center for Small Town Jewish Life have chosen a unique response to this moment of increased Jewish vulnerability and alienation. We have reinforced local partnerships, introduced citizens from all walks of life to the beauty of the Jewish tradition, and invited them to participate, not just as observers, but as co-creators.

Even though there are potential risks, and deficiencies to this approach, it builds on the strengths and spirit of small town Jewish life. We affirm our place in our community through sharing our traditions, and placing them in a greater American and social context, one that emphasizes faith, family, and community. Building friendships and understanding may not protect us from all animus, but it does reduce suspicion and dehumanization. Our festival is made all the more joyous when we see our neighbors celebrating with us, and when we learn about their journeys, families and creative gifts.

Through constructing Sukkot in this way, our local Jewish community gains or develops or cultivates a greater sense of pride, happiness, fulfillment and “at homeness” in Waterville. And through erecting this temporary Jewish structure in shared civic space on Main Street, Waterville is stronger. Our prophets teach that when the world is ultimately redeemed on Sukkot, the Temple will become a house of prayer for all peoples. Although we are miles away from a rebuilt Jerusalem, we are beginning that redemptive process in Waterville, Maine, beam by beam, branch by branch, citizen by citizen.

—

The post In my small town, ‘that Jewish hut’ has turned Sukkot into a cross-cultural shelter of peace appeared first on Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

Uncategorized

Stories of loss and heroism featured in Toronto’s commemoration of Oct. 7

Personal stories of lost loved ones, including the mother of one of the eight Canadians who was killed, and a harrowing, heroic tale of a man who rescued more than 100 people from the attack on the Nova music festival, marked the two-year commemoration of the Oct. 7, 2023 Hamas-led attacks on Israel.

The UJA Federation of Greater Toronto event on Oct. 5 at Beth Tzedec Congregation featured the stories of Raquel Look, mother of Alexandre Look, who died saving others during the Nova Festival attacks, and Oz Davidian, who rescued 120 teenagers in more than 15 trips in his truck, as detailed in the 2024 documentary Oz’s List.

Hundreds of attendees, including numerous elected officials, took in the program, including Toronto Mayor Olivia Chow, whose absence at the previous year’s commemorations drew criticism and compounded frustrations with Chow’s office from many Jewish community members.

Sporting a yellow ribbon pin for the hostages, Chow was among several public officials in attendance, including Ontario Premier Doug Ford, former Toronto mayor John Tory, Vaughan Mayor Steven Del Duca, MPs Melissa Lantsman and Leslie Church, and a host of Toronto and Vaughan city councillors and provincial MPPs.

Attendees were greeted by a number of visual exhibitions, including a series of photos and text along a corridor telling the stories of Oct. 7 in Israel and the community’s experience in Toronto since that day, with a record 56,000 participants at the Walk With Israel last May.

Outside the synagogue’s sanctuary, where the program was held, in a quieter Yahrzeit memorial space, a series of small lightbulbs, and their reflection on the wall, represented the 1,200 lives lost in the attacks. Participants activated the lights by turning the bulbs, which slowly illuminated the otherwise dark space during the event.

A third installation comprising 48 giant yellow ribbons on stands, and signs named each of the remaining hostages, of whom around 20 are estimated to be alive, and focused on the return of those captives, who by the Oct. 5 event had been held for 730 days in Gaza.

The program included songs, prayers of mourning, and a featured conversation with Look, followed by Davidian’s self-narrated tale of rescuing festivalgoers, shared onstage through a translator.

Idit Shamir, Consul General of Israel for Toronto and Western Canada, recalled the death of her cousin, who stayed during the evacuation call at Kibbutz Kissufim, to feed the animals, she said, before describing how terrorists came through the door and shot the 70-year-old man, then dragged and manipulated his bloody body and posed for a selfie— “making sure the world saw,” she said.

“Two years ago, I saw pure evil. So did you,” Shamir said. “And since that day, I stopped being who I was before. I think we all did.”

She spoke about the responsibility, as Israel’s representative, to the families of the eight Jewish Canadians who were killed in the attacks, weaving their life, and death, stories into her tribute.

“I carry the weight of my nation’s pain and my responsibility to honour these heroes,” Shamir said.

“Alexandre Look, who ran towards danger to save others, until courage cost him everything. Tiferet Lapidot, who painted her dreams in Canadian colours, and Israeli light, until darkness came. Judih Weinstein Haggai, whose poetry touched souls on two continents, until silence fell. Vivian Silver, who dedicated her life to peace, driving Palestinians to Israeli hospitals, until hatred claimed her.

“Netta Epstein, who jumped on a grenade to save his girlfriend. Shir Georgy, who danced between worlds, until the music stopped. Adi Vital-Kaploun, who protected her babies with her life, but they were still carried to Gaza. Ben Mizrahi, who carried Vancouver’s rain to Israel’s desert, until storm clouds gathered.”

Shamir commented on the difficulty of measuring “two years that changed everything,” describing the tensions that have unfolded in Canada since the attacks and subsequent war, including the “denial, celebration, and justification, here in Canada and around the world” of the Oct. 7 attacks.

“The traumatic impact of that day has not gone away,” she said.

“We measured it in shock, at the escalating harassment, violence, and intimidation against us… [in] the support for terrorism, the indoctrination of youth, the attempts to erase our voices, and make us into pariahs. Physical attacks on schools, synagogues, and Jewish-owned businesses. The boycotts. The demands made only for Jews. Teaching materials that erase Israel from the map. Indoctrinating children … yes, even here in Toronto,” she said.

“What we saw on the streets of Toronto, and across Canada, for the past two years, the calls for intifada, the flags of a listed terror organization, goes well beyond peaceful protest. It goes beyond antisemitism. This is a declaration of war against our Western values.”

In a moderated discussion, Look explained to—or, in some cases, reminded—audience members that she had been in contact with her son between the start of the attacks and his death at their hands, trying to fight them off and protect others at a bomb shelter with no door where he and other festivalgoers had taken cover.

Look and her son had spoken for an hour-and-a-half that morning, in between Alexandre’s momentary safety, and the attackers’ return.

When asked how she now draws strength, Look (who attended with husband Alain, Alexandre’s father), said she taps into her courage by remembering what her son faced compared to what she needs to do.

“I say to myself, if he was brave enough to face pure evil, I can be brave enough to put on my Magen Davids all over myself, and speak and be a voice for him, for all the ones that sadly, their voices, their lives were taken away, so young, so brutally,” she said.

“We are the descendants of the Maccabees,” she said to applause. “October 7 will be the last massacre on Jewish people that we will memorialize.”

The documentary’s title, Oz’s List, Davidian explained, came from the list of survivors he started after he’d begun ferrying stranded teens from the festival site to safety at his moshav.

He described taking back routes through valleys and fields to avoid the road where armed terrorists would be waiting. Then, during one of his return trips to find survivors, he realized his white pickup truck resembled that of the Hamas-led attackers, and pinned an Israeli flag in the truck cab to signal safety for any living festivalgoers he could pick up.

“They understood I’m one of them, and I came to rescue them,” he recounted through translator Tomer Regev.

In one trip, he managed to take 17 teenagers, he said. Later, reaffirming if he would do it all again, Davidian said he would.

“It’s my country … my people,” he said, through Regev. “These are our brothers. These are our children.”

Noah Shack, CEO of the Centre for Israel and Jewish Affairs (CIJA), noted that the moment of reflection two years after Oct. 7 came after a terrorist attack last week on Yom Kippur, in Manchester, England, where two people were killed and others were seriously injured.

“We’re seeing that the same violence that occurred two years ago is still alive and well, targeting Jewish people, not just in Israel, but around the world,” he told reporters.

He called for government leaders to take “urgent action to push back against the radicalization that we’re seeing, the glorification of terrorism and violence and the anti-Jewish hate that’s festering and leading to these attacks taking place.” He mentioned attacks on synagogues since Oct. 7, and the stabbing last month of a Jewish woman in a supermarket in Ottawa.

“These are things that should not be happening in Canada, to our community or to any community.”

Still, while “it’s important for our community to stay focused on what matters,” he said, including the remaining hostages and “the righteousness of our cause in fighting against terror” and hate, Shack reminded the Jewish community it does have support from a range of Canadians.

“There are many who stand with us, far more Canadians who are with us than who are against us.”

Daniel Held, UJA’s chief program officer, wants non-Jewish Canadians to understand the community’s current security needs, and what’s behind those expenditures.

“We’re on High Holidays. We come under guard and under incredible security because we are under threat,” he said. “Our community has been forced to spend tens of millions of dollars on security.”

Still, he noted, the community yearns for hopeful news about the hostages, and a peace deal, from Israel.

Talks between Israel, Hamas, and mediators including U.S. representatives were ongoing in Egypt this week to discuss U.S. President Donald Trump’s 20-point peace proposal.

Elsewhere in the Greater Toronto Area on Oct. 5, Raquel Look joined the weekly Run For Their Lives event in Thornhill, Ont., while other weekly events included the 105th edition of the Rally for Israel at Bathurst Street and Sheppard Avenue in the north end of Toronto.

Fashion designer Rinat Samuel, who since Oct. 7 has created T-shirts with the slogan “it’s not fashionable to be antisemitic!” and others, held a photo shoot at North York’s Mel Lastman Square.

And, in downtown Toronto, the Miles Nadal JCC hosted a sunrise pre-Sukkot ceremony early on Oct. 6, led by Beth Tzedec’s Aviva Chernick and Yacov Fruchter, to “mark this tender moment in the calendar” as a community.

The post Stories of loss and heroism featured in Toronto’s commemoration of Oct. 7 appeared first on The Canadian Jewish News.