Uncategorized

What a forgotten synagogue dedication in 1825 Philadelphia can teach us today

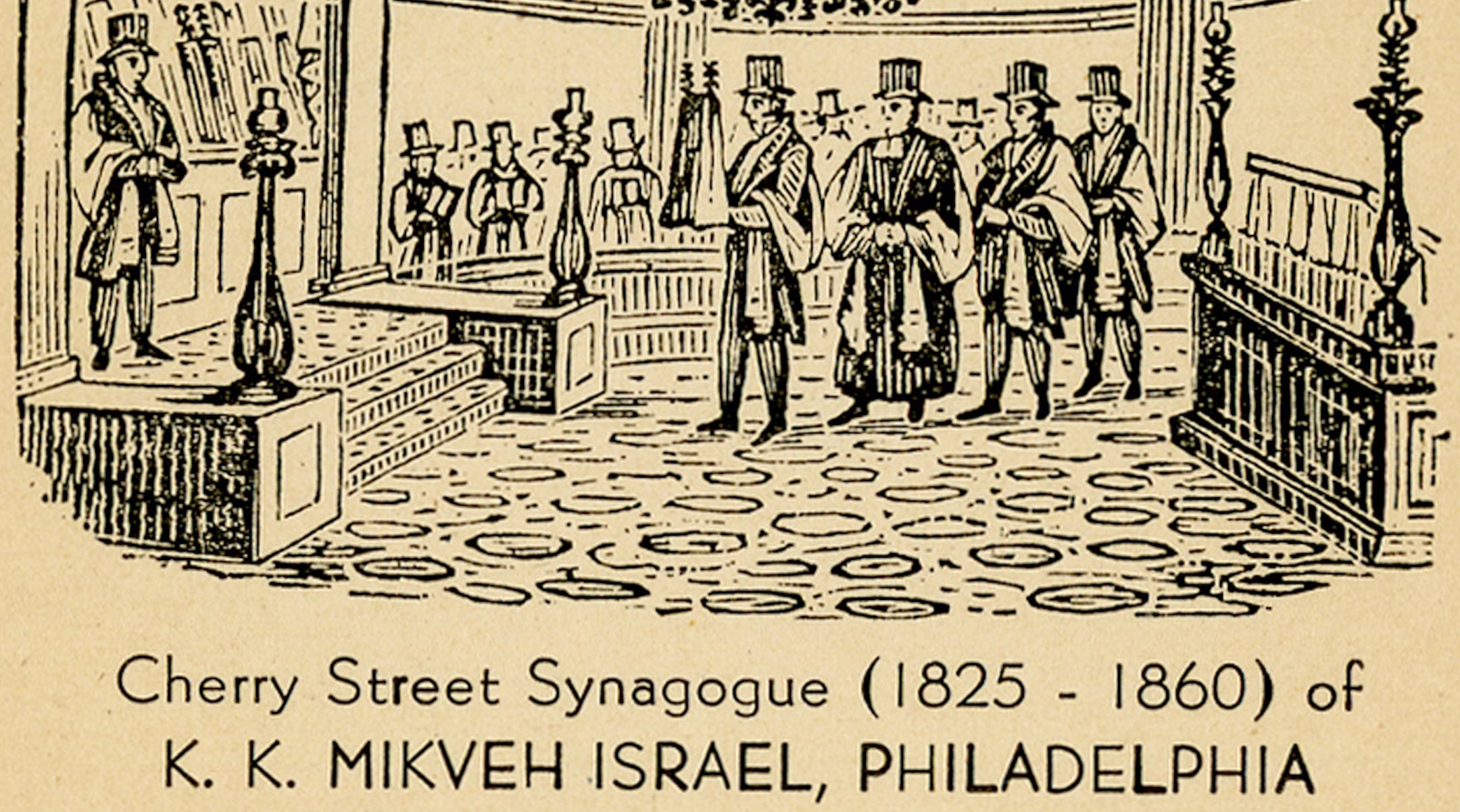

On a winter morning in 1825, Congregation Mikveh Israel in Philadelphia opened its doors for a consecration few in the city would forget.

The sanctuary filled not only with Jews but with the city’s civic and religious leaders. Bishop William White, the Episcopal bishop of Pennsylvania, was there. So too were the chief justice and associate judges of the state Supreme Court, along with ministers from other Christian churches and “many other distinguished citizens.”

The newspaper that covered the event could hardly contain its admiration. It called the ceremony “one of the most gratifying spectacles we have ever witnessed,” praising it as evidence of “the happy equality of our religious rights, and the prevailing harmony among our religious sects.”

For Europeans in attendance, the sight was almost inconceivable. They remarked that such a scene could not be witnessed “in any other part of the world” — Jews worshiping openly, honored by civic leaders, regarded as full equals. They urged that the moment be noticed abroad “for the instruction and edification of Europe.”

This long-forgotten consecration reveals something about Jewish life in America that is too often overlooked. Alongside well-known stories of antisemitism and exclusion, there have long been moments when Jewish life was welcomed as part of the civic square — when synagogue dedications became community milestones, not private affairs.

Just three years earlier, when Mikveh Israel laid the cornerstone for its building, its members placed into the foundation a copy of the U.S. Constitution, the constitutions of several states, and American coinage. Embedding the nation’s founding charter into the walls of a synagogue was both symbolic and aspirational.

In Europe, the picture was far more precarious. In Wiesbaden in 1826, Jews converted a garden hall into a synagogue. The community’s rabbi, Salomon Herxheimer, preached a sermon heard by neighbors “without distinction of worship.” Yet this was a fragile moment of recognition. For centuries, Wiesbaden’s Jews had lived as Schutzjuden — “protected Jews” — dependent on the goodwill of local nobles, barred from land ownership, and restricted in their trades. Only in 1819 were they granted theoretical freedom of commerce, and even then, their rights remained uncertain.

Similar stories unfolded later in Munich in 1869, where the King of Bavaria donated land for a synagogue, or in Berlin in 1866, where thousands, including Otto von Bismarck, gathered in a new sanctuary that newspapers as far away as Australia described with awe. These were real milestones, but they were fragile. Within living memory, those very synagogues would be destroyed on Kristallnacht in 1938.

The contrast is telling. In Philadelphia, non-Jews filled a synagogue in 1825 to celebrate Jews as civic equals. In Central Europe, recognition also came, but less often — and it was never secure.

Jewish history is often told as a story of persecution — expulsions, pogroms, restrictions. That history is real, but it is not the whole story. There have also been times, often little remembered, when Jews were embraced as neighbors and citizens. Ancient Judaism was visible far beyond the Land of Israel — in places like Adiabene (in northern Iraq) and Himyar (in Yemen) — and its theology helped shape the rise of both Christianity and Islam. In medieval Spain, convivencia — imperfect but real — allowed Jewish culture to flourish alongside Muslim and Christian communities. For generations in small towns across America, non-Jews sometimes contributed money, labor, or land to help build synagogues.

These histories matter because they remind us that belonging is never preordained. It is chosen in every generation — and it is possible.

Today, that lesson feels urgent. Antisemitism is again on the rise, from violent attacks like the one on Yom Kippur in Manchester to the spread of conspiracy theories online. Debates over Zionism and the future of Diaspora life have also become more polarized, often framed in absolutes: either Jews can only be safe in a sovereign state, or Diaspora life is doomed to fade away.

The 1825 consecration in Philadelphia tells another story. It shows that Jewish life in the Diaspora has not only survived but, especially in places like the United States, thrived in public — long embraced as part of the civic fabric. It also shows how precious those moments can be: roots of belonging that must be tended, not assumed.

As Europeans present that day observed, America’s pluralism was something worth sharing with the world. Nearly two centuries later, the challenge remains the same. Do we remember these paths of belonging, or do we forget them and leave only the stories of hatred to define our past?

I first began asking these questions while researching small-town Jewish communities in Ohio and New York. In many of those places, the synagogues are gone and the Jewish population has dwindled, yet I found records of interfaith choirs singing, neighbors contributing to building funds, and civic leaders marching alongside rabbis.

Those memories could easily vanish. In Lancaster, Ohio, my hometown, the synagogue closed in 1993, its building later sold. Yet the remaining members created a Jewish book fund that allowed me, years later, to discover a volume of Jewish learning in the local library — a spark that shaped my own path into Judaism.

Who tells these stories when the buildings are gone and the communities have disappeared? Who remembers the moments of belonging as well as the moments of exclusion?

The consecration of Mikveh Israel in 1825 was, for its witnesses, proof that something remarkable was possible: Jews and non-Jews together, celebrating equality, showing Europe another way. We should remember that moment not as a quaint curiosity but as a challenge. Belonging is not guaranteed. It must be chosen in each generation, in every place.

The people who filled that sanctuary in 1825 knew this. They saw in Philadelphia something they believed could not be found elsewhere — a vision of belonging worth teaching the world.

—

The post What a forgotten synagogue dedication in 1825 Philadelphia can teach us today appeared first on Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

Uncategorized

Gunmen Kill Three People and Abduct Catholic Priest in Northern Nigeria

A police vehicle of Operation Fushin Kada (Anger of Crocodile) is parked on Yakowa Road, as schools across northern Nigeria reopen nearly two months after closing due to security concerns, following the mass abductions of school children, in Kaduna, Nigeria, January 12, 2026. Photo: REUTERS/Nuhu Gwamna/File Photo

Gunmen killed three people and abducted a Catholic priest and several others during an early morning attack on the clergyman’s residence in northern Nigeria’s Kaduna state, church and police sources said on Sunday.

Saturday’s assault in Kauru district highlights persistent insecurity in the region, and came days after security services rescued all 166 worshippers abducted in attacks by gunmen on two churches elsewhere in Kaduna.

Such attacks have drawn the attention of US President Donald Trump, who has accused Nigeria’s government of failing to protect Christians, a charge Abuja denies. US forces struck what they described as terrorist targets in northwestern Nigeria on December 25.

The Catholic Diocese of Kafanchan named the kidnapped clergyman as Nathaniel Asuwaye, parish priest of Holy Trinity Catholic Church in Karku, and said 10 other people were abducted.

Three residents were killed during the attack, which began at about 3:20 a.m. (0220 GMT), the diocese said in a statement.

A Kaduna police spokesperson confirmed the incident, but said five people had been abducted in total and that the three people killed were members of the security forces.

“Security agents exchanged gunfire with the bandits, killed some of them, and unfortunately two soldiers and a police officer lost their lives,” he said.

Rights group Amnesty International said in a statement on Sunday that Nigeria’s security crisis was “increasingly getting out of hand”. It accused the government of “gross incompetence” and failure to protect civilians as gunmen kill, abduct and terrorize rural communities across several northern states.

A presidency spokesperson could not immediately be reached for comment.

Pope Leo, during his weekly address to the faithful in St. Peter’s Square, expressed solidarity with the victims of recent attacks in Nigeria.

“I hope that the competent authorities will continue to act with determination to ensure the security and protection of every citizen’s life,” Leo said.

Uncategorized

Israeli FM Sa’ar Stresses Gaza Demilitarization, Criticizes Iranian Threats in Talks with Paraguay’s Foreign Minister

Israeli Foreign Minister Gideon Sa’ar speaks next to High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy and Vice-President of the European Commission Kaja Kallas, and EU commissioner for the Mediterranean Dubravka Suica as they hold a press conference on the day of an EU-Israel Association Council with European Union foreign ministers in Brussels, Belgium, Feb. 24, 2025. Photo: REUTERS/Yves Herman

i24 News – Foreign Minister Gideon Sa’ar made the remarks on Tuesday during a meeting at the Foreign Ministry in Jerusalem with Paraguay’s Foreign Minister Rubén Ramírez Lezcano. The meeting included a one-on-one session followed by an expanded meeting with both countries’ bilateral teams.

Sa’ar told the media, “We support the Trump plan for Gaza. Hamas must be disarmed, and Gaza must be demilitarized. This is at the heart of the plan, and we must not compromise on it. This is necessary for the security and stability of the region and also for a better future for the residents of Gaza themselves.”

He also commented on Iran, saying, “I praise President Peña’s decision in April of 2025 to designate Iran’s Revolutionary Guards as a terrorist organization. The European Union and Ukraine have also recently done so, and I commend that. The Iranian regime is murdering its own people. It is endangering stability in the Middle East and exporting terrorism to other continents, including Latin America. The attempt by the world’s most extremist regime to obtain the most dangerous weapon in the world, nuclear weapons, is a clear danger to regional and world peace.”

Sa’ar added that Iran’s long-range missile program threatens not only Israel but other countries in the Middle East and Europe. “The Iranian regime has already used missiles against other countries in the Middle East. European countries are also threatened by the range of these missiles,” he said.

Lezcano praised his country’s decision to open an embassy in Jerusalem. “Paraguay’s sovereign decision to open its embassy in Jerusalem was made in faith and responsibly. It reflects the coherent foreign policy that we consistently and clearly hold with regard to Israel,” he said. He added that Paraguay “unequivocally and unquestionably supports the right of the State of Israel to exist and to defend itself,” a position reinforced after the October 7, 2023, attacks.

Uncategorized

In Economic Speeches, Trump Claims Inflation Victory Nearly 20 Times Even as Prices Bite

US President Donald Trump gestures on the day he delivers a speech on energy and the economy, in Clive, Iowa, US, January 27, 2026. Photo: REUTERS/Kevin Lamarque/File Photo

Donald Trump has cast himself as Republicans’ chief messenger on the cost of living in an election year, but a Reuters review of his speeches shows a president repeatedly declaring inflation beaten while rarely acknowledging the strain many Americans say they still feel.

In five speeches on the economy since December, Trump asserted that inflation had been beaten or was way down almost 20 times and said prices were falling almost 30 times, assertions at odds with economic data and voters’ daily experiences. Much of the remaining time was spent on grievances and other issues, including immigration, whether Somalia was a country, and attacks on opponents.

Taken together, the speeches portray a president struggling to reconcile his central claim — that he has fixed the cost-of-living crisis — with inflation near 3% over the past year and voters’ lived experience of paying more for grocery staples. The price of ground beef, for example, is up 18% since Trump took office a year ago, while ground coffee prices are up 29%.

Republican strategists told Reuters that his mixed messaging on the top issue for voters risks creating a credibility gap for him and the Republican Party ahead of the November midterms, when control of Congress will be at stake. Opinion polls show voters are deeply unhappy with Trump‘s handling of the economy.

“He can’t continue to make claims that are demonstrably false, particularly at the expense of Republicans who are in competitive House districts or Senate races,” said Rob Godfrey, a Republican strategist. Trump “must be disciplined and focused,” he added.

One source close to the White House said the president needed to hit the issue of affordability harder and through personal visits to critical districts.

“He needs to bring the message out because the message is not resonating,” the source said, speaking on condition of anonymity to more freely discuss the issue.

Kush Desai, a White House spokesman, said Trump’s focus on illegal immigration in his speeches is directly connected to his argument that people in the country illegally have an adverse impact on the economy. Desai said it causes “public services being overburdened, business activity disrupted by crime, housing markets flooded, and workers’ wages depressed.”

Trump has repeatedly stressed that much work remains to clean up the economic mess he says his Democratic predecessor, Joe Biden, left him, Desai added.

TRUMP VEERS OFF MESSAGE TO RAIL ABOUT IMMIGRATION

The Reuters analysis found that Trump – when not declaring inflation beaten – devoted nearly half his speaking time to grievances and other issues.

In about five hours of speaking time, he spent roughly two hours straying into about 20 topics unrelated to prices, the Reuters review found. When he veered off message, his top issue was illegal immigration, which he spent a total of about 30 to 40 minutes talking about.

In the speeches he insulted Somali Americans in Minnesota, who voted against him in the 2024 election. He referred to Somalia as “not even a country” – and in four speeches he disparaged Somali-born Minnesota congresswoman Ilhan Omar.

A progressive, high-profile Democrat and Muslim, Omar has been a frequent Trump critic, especially over his immigration policies.

“Every time the president of the United States has chosen to use hateful rhetoric to talk about me and the community that I represent, my death threats skyrocket,” Omar said last month, the day after a man sprayed a foul-smelling liquid on her at a town hall event.

Trump also talked about men in women’s sports, Venezuela, Iran, the Islamic State militant group, Greenland, Ukraine and Russia, military recruitment, his false claim that the 2020 election was rigged, US weaponry, his exaggerated claim to have ended eight wars, and even how much a Fox News anchor likes him.

TRUMP‘S MEANDERING WORRIES STRATEGISTS

“Inflation is stopped. Incomes are up. Prices are down,” Trump said in an Iowa speech on January 27.

Only twice in the five speeches did Trump acknowledge that prices are still too high, but he blamed them on Biden. Trump was elected in 2024 because of voter unhappiness with Biden’s handling of inflation – which spiked to over 9% in 2022 – and illegal immigration.

Democrats caused prices “to be too high,” Trump told a rally in Pennsylvania on December 9. “But now they’re coming down.”

In the same speech he called the term “affordability” a Democratic “hoax”. After a public backlash, he has ceased saying that in more recent speeches.

In four of the speeches Trump repeatedly and haphazardly switches topics, often when he is in the middle of talking about the economy, the Reuters review found.

Four Republican strategists interviewed by Reuters said Trump‘s meandering style – which he proudly calls “the weave” – risked drowning out his core economic argument that he has brought inflation and prices down.

Speaking to world leaders at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland on January 21, Trump spent the first 22 minutes on topic, then suddenly, for the next 22 minutes, insulted Europeans, said they would be speaking German if it wasn’t for America, called NATO ungrateful, and decried the “crooked” media before pivoting back to the US economy.

Doug Heye, a Republican strategist, said voters want to hear what Trump is doing to lower costs. “But they have no memory of what Trump says about economic issues because of the volume of his own rhetoric.”

One source familiar with the White House’s thinking said Trump was likely to use his State of the Union address on February 24 as the kickoff for more intense domestic travel to amplify his message on affordability.

TRUMP DOES OFFER SOLUTIONS

For many Americans, the economy still feels unforgiving. Prices remain high, even though the inflation rate has inched down since Trump took office, from 3% to 2.7%. A lower inflation rate does not mean prices are decreasing – just that they are growing at a slower pace, economists stress.

In the 12 months through December 2025, food costs were up over 3%, while average hourly earnings were up only 1.1% year over year. The unemployment rate was 4.4% in December, up from 4% when Trump took office in January 2025, according to government data.

In some of the speeches Trump correctly identifies a drop in prices for a few everyday goods, including eggs and gas. The cost of eggs fell about 21% in December from a year earlier after being 60% higher during Trump‘s first months back in office. Gas prices are about 4% lower since January last year.

But the cost of an average grocery basket has risen. The price of coffee, beef, and some fruits, among other items, has risen in the past year.

Trump does offer solutions in his speeches, including his tax cuts that kicked in last month that will produce greater savings for tens of millions of families; the scrapping of taxes on tips, overtime and Social Security payments; his plan to reduce mortgage interest rates; a proposal to lower housing prices; and deals with health insurance companies to reduce drug prices.

Most economists expect US households and the economy at large to benefit in the months ahead from the tax cuts. But Trump‘s more recent proposals are unlikely to have a significant impact on the cost of living between now and November, some economists told Reuters. One of Trump‘s ideas – to cap credit card interest rates to 10% for a year – could even backfire since it could limit access to credit for lower-income families, some economists have warned.

Mike Marinella, a spokesman for the National Republican Congressional Committee, which supports candidates for the House of Representatives, said Trump and Republicans were helping working families. “Voters are seeing this clear contrast, and the best is yet to come.”

Some 35% of Americans approve of Trump‘s overall handling of the economy, according to a January 25 Reuters/Ipsos poll, up slightly from 33% in December. But it is well below his initial 42% rating on the issue when he first took office a year ago.

FALLING INTO BIDEN TRAP

Former economic officials in previous administrations say Trump is falling into the same trap Biden did in 2024 when confronted with persistently high inflation.

Biden kept claiming the US economy was strong and urged voters to look at other economic data. That strategy failed badly and Democrats were punished at the polls.

The officials agreed it was important for presidents to show voters they understood their economic pain, especially in an election year.

“We definitely talked past people on inflation,” Jared Bernstein, the head of Biden’s Council of Economic Advisers, said in an interview.

“What we typically did was to say, ‘A new report just came out on jobs, it’s very strong,’ and that was all true. But the fact is that there wasn’t much we were able to do in terms of the price level.”