Uncategorized

Elie Wiesel as an American phenomenon and a family man

How do you tell a story that everyone knows? Oren Rudavsky, in the opening scenes of his recently released documentary Elie Wiesel: Soul on Fire, makes the wise decision to begin his film not through the known facts about Wiesel or the Holocaust, but through a more internal logic of art and dreams.

As Wiesel narrates a dream, we see Joel Orloff’s hand-painted animation of dark figures succumbing to a rising river of blood, leaving the dreamer alone to try to rescue his drowning father. Fingers grasp at bodies as they slip under.

“I don’t know what power aided me,” we hear Wiesel say. “All I know is that I managed to save him all by myself.” As anyone who has read Night knows, Wiesel’s father succumbed to dysentery in Buchenwald. That Elie could not save his father, his wife Marion tells us, was the abiding wound he always carried.

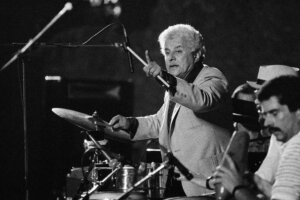

Dreams, in Freud’s view, are wish fulfillments. But this dream-act of (temporary) reanimation also expresses Wiesel’s conviction that the dead are not entirely gone if they are remembered. That may be the redemptive vision that drives Rudavsky, as well. The implicit hope that the dead may be saved opens the film and breaks into full voice at its ending, with Wiesel beautifully singing the messianic anthem “Ani Ma’amin” from the stage of the 92nd Street Y.

As he sings, his face gives way to a lush, grassy landscape rushing by as if we’re passengers on a train, while his voice fades into a choral arrangement. In moving past Wiesel’s face and voice, the film embodies and fulfills Wiesel’s belief that the Jewish story will continue, on PBS as in his family line.

For all its focus on European catastrophe and Jewish longings, the documentary casts Elie Wiesel as an “American Master,” the title of the larger PBS series. Wiesel is an American phenomenon, read in classrooms around the country and, for a time, in the White House. Full disclosure: I appear briefly in the film, discussing the reception of Wiesel’s work and the difference between the Yiddish title of his best-known work, Un di velt hot geshvign (And the world kept silent) and the French/English title of its translation, La Nuit (Night).

One of the film’s extended sequences captures a moment that saw Wiesel at the center of American politics and the global stage, when he passionately implored President Reagan to cancel a planned visit to the German military cemetery in Bitburg, once it had become known that Waffen-SS soldiers were buried there. “That place is not your place,” Wiesel says on national TV, with Reagan looking on. “Your place is with the victims of the SS.”

Details less engraved on collective memory emerge from Rudavsky’s film: the shared friendship both men describe, the attempts behind the scenes to ameliorate the clash, Wiesel’s insistence that he was making no claims about German collective guilt. “Only the killers were guilty,” he said.

This episode establishes Wiesel’s courage and role as a preeminent moral voice of his time. Less clear is the trajectory from the solitary writer in postwar Paris to the man who came to represent the Holocaust experience, when his novel/memoir Night became required reading.

One of the brilliant 13-year-old students who discuss the novel in their Newark classroom suggests such an analysis, in distinguishing between the Eliezer of the story and Elie Wiesel, its famous author. In America and elsewhere, Wiesel became so closely associated with Holocaust memory that the Eliezer/Elie distinction, or alternatives to his distinctive voice, are hardly imaginable.

Not one but two stories drive Rudavsky’s documentary: one of unimaginable catastrophe and loss; and another of privilege and success — both Wiesel’s own stature and the broader rise of the American Jewish community in which this story is embedded. How these two narratives are related is a tale that remains to be told.

And yet, alternatives to Wiesel’s powerful voice are heard in the film. Remarkably enough, they emerge from Wiesel’s own family. Marion Wiesel, who married the war-haunted bachelor when he was 40, recounts that her husband had insisted “from the beginning that he didn’t want children.” And then she adds: “I convinced him.”

Photographs of her during those years as a bride and new mother radiate, and we see the hint of a smile on her husband’s mournful visage. As an old woman, she commands attention. Against the widespread veneration of Wiesel’s pronouncements, she shows herself at least occasionally unpersuaded. Describing Wiesel’s growing religiosity, she comments drily, “I was the pagan in the family.” Served a latke at a family Hanukkah celebration that could easily be played for sentimentality (“the Jewish people live!”), she sniffs: “Doesn’t look like a latke.”

Marion Wiesel’s acerbic tone is particularly welcome as commentary on a topic of increasingly pressing concern. Elie Wiesel, in his Nobel Peace Prize lecture, asserts that he is sensitive to the plight of the Palestinians, “but whose methods I deplore when they lead to violence.” Marion comments: “He didn’t want to criticize Israel under any circumstance. He didn’t want to criticize the occupation. He didn’t want to criticize the settlers. He may not have agreed with them, but he didn’t want to criticize them. Ever.”

In contrast with the moral clarity of his words about Bitburg, what the film presents us with on this issue is a muddle, and if I am reading Marion right, a bit of a family dispute. In this way, the Wiesel family was no different from so many others.

So, too, does Rudavsky complicate Wiesel’s devotion to Jewish survival in focusing on the discomfort of Elisha Wiesel, the couple’s only son, in the role of living symbol of Jewish continuity. Cuddled on Jimmy Carter’s lap, called to the stage at Oslo, Elisha remembers chafing at being “just an appendage” to his famous father.

And yet, as the film ends, he, too, has embraced Judaism anew, laying tefillin on camera. Elisha’s son, Elijah, also takes up the imperative and burden of Holocaust memory, traveling to Sighet to visit his grandfather’s childhood home, now turned into a museum.

In a stirring scene, the Hebrew letters on the gravestone of his namesake — his great-grandfather — appear with growing clarity, illuminated by the trick of scraping shaving cream off the inscription (not recommended by conservators) and the magic of documentary film.

And yet, Elijah Wiesel with the waist-long hair is not the Eliyahu Vizel of the gravestone, just as Eliezer Vizel of Sighet is not quite the same as Elie Wiesel of Oslo and Boston. “Jewish continuity” is a bridge we narrate over the shifting sands of loss and change. The present, past, and future connect for a fleeting moment, only to drift apart like a dream, a film.

The post Elie Wiesel as an American phenomenon and a family man appeared first on The Forward.

Uncategorized

BBC Issues Correction After Claiming ‘There Have Been Other Holocausts’ in Response to Complaint

The BBC logo is seen at the entrance at Broadcasting House, the BBC headquarters in central London. Photo by Vuk Valcic / SOPA Images/Sipa USA via Reuters Connect

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) has been accused of “trying to downplay or deny the horror of the Holocaust” after the broadcaster claimed “there have been other holocausts [sic]” when responding to a complaint by a reader about an online article.

The BBC posted on its website an article about King Charles III and Queen Camilla meeting with survivors of Nazi persecution to mark International Holocaust Remembrance Day on Jan. 27. According to Jewish News, the article originally stated that Bergen-Belsen concentration camp survivor Mala Tribich “became the first holocaust [sic] survivor to address the cabinet,” and she asked ministers: “How, 81 years after the holocaust [sic], can these people once again be targeted in this way?”

A reader wrote a complaint about the article using a lowercase “h” in the word “Holocaust” and received a response via email in which the BBC rejected the request to make the change but did not explain why. The reader was also told in the email, “Historically there have been other examples of holocausts [sic] elsewhere,” according to Jewish News. The email was reportedly written by an experienced BBC broadcast journalist.

The BBC has since edited the article to feature an uppercase “H” in the word “Holocaust” and added a note to the online article. “Several references to ‘Holocaust,’ which had been initially spelled in this article with a lower case ‘h,’ have been changed to take an upper case ‘H,’ in accordance with the BBC News style guide,” the BBC wrote. A BBC spokesperson further told Jewish News the email to the reader had been “sent in error.”

“All references to the Holocaust in this article should have been capitalized and we have now updated it accordingly and added a note of correction. We will be writing again to the original correspondent,” the spokesperson noted.

The Campaign Against Antisemitism (CAA) was outraged by the BBC’s error, and said the incident is another example “of an institutionalized dismissal or even hatred of Jews that permeates the BBC’s increasingly agenda-driven reporting.”

“Why is the BBC effectively joining far-right, far-left, and Islamist propagandists and conspiracists in trying to downplay or deny the horror of the Holocaust?” CAA posted on X. “The BBC is peddling softcore Holocaust denial by trivializing the name of this horrific crime.”

“It is difficult to know where the monumental ignorance of the BBC news and complaints divisions ends and their willful revision of history begins,” the organization added. “The Nazi slaughter of the Jews was so extensive that the word genocide had to be invented to describe it. While that word has since been applied to other attempts to wipe out whole peoples, the older word ‘holocaust’ was newly adapted to this event, with which it is uniquely associated.”

The BBC just recently issued an apology after it failed to mention Jews during some of its coverage of International Holocaust Remembrance Day.

Uncategorized

‘You Really Saved Me’: Pianist, Former Hamas Hostage Dedicates Performance to Fellow Survivor Eli Sharabi

Former hostage Alon Ohel reacts as he is welcomed home, after he was discharged from the hospital following his release from captivity in Gaza, where he was held after being kidnapped during the deadly Oct. 7, 2023, attack by Hamas, in Lavon, Israel, Oct. 24, 2025. Photo: REUTERS/Shir Torem

A musician and former Hamas hostage returned to the stage on Monday night in Israel for a performance and dedicated a song to fellow survivor Eli Sharabi, who was his companion in captivity.

Israeli-Serbian pianist Alon Ohel survived 738 days in captivity in the Gaza Strip after being kidnapped when he tried to flee the Nova Music Festival in southern Israel on Oct. 7, 2023. He was released more than two years later, on Oct. 13, 2025, along with the last remaining 20 living hostages. Ohel was held for some time in Hamas’s tunnels alongside Sharabi, who was abducted from Kibbutz Be’eri on Oct. 7, 2023, and released last February.

Several Israeli artists performed on Monday evening as part of a concert for Ohel at Hangar 11 in Tel Aviv.

At one point during the event, Ohel went on stage and did a solo performance of “Yesh Li Sikui” (“I Have a Chance”) by singer-songwriter Eviatar Banai. Ohel dedicated the song to Sharabi, who was standing in the audience.

“In a way, you really saved me with your approach to life,” Ohel said to Sharabi from on stage.

The pianist then shared memories of sitting with Sharabi in the terror tunnels. “We had backgammon or some card game. We played and laughed a bit, and joked around, and I remember you mentioned my mother’s name, Idit, and in that moment I fell apart,” he said. “I couldn’t handle it. The longing broke me in an instant. I went aside and cried. I just cried and broke down. A longing that never ends.”

“After you let me fall apart, I remember you came over to me,” Ohel added, still addressing Sharabi. “You told me: ‘Alon, you have to pull yourself together. You have to disconnect. This can’t work like this. You broke down, now that is it, you pick yourself up. You’re a big kid and we have one goal: to return to our families no matter what. It’s okay to break down, but we must never lose hope.’”

Ohel then recalled how after a year and a half of being together in the terror tunnels, during which time the two men were chained to each other, Sharabi was taken away and Ohel was held in captivity alone.

Sharabi’s words helped him get through those lonely days, Ohel admitted. He told Sharabi on Monday night: “I continued with the mantras you taught me, the ones you kept drilling into my head: ‘Be mentally strong and optimistic,’ and I added being calm in soul. This is my opportunity to say thank you.”

Monday night’s concert featured many artists, including Idan Amedi, Shlomi Shaban, Alon Eder, Gal Toren, Guy Levy, and Guy Mazig. All proceeds went toward a rehabilitation fund for Ohel.

Uncategorized

Why Bad Bunny’s halftime show delighted New York Jews of a certain age

Since last month, a TikTok has been floating around, showing arthritic Latino grandmas and grandpas hearing Bad Bunny for the first time, courtesy their bemused grandchildren. On the reel, he samples “Un Verano en Nueva York,” a 50-year-old salsa song about New York City — or “Nueva Yol,” as Bad Bunny calls his update in his echt Puerto Rican accent. He sang “Nueva Yol” at the Super Bowl halftime show. The original dates from the 1970s, when the old folks were young and lithe and out on the town. On TikTok, when they listen to the new version, they perk up, and then they dance, as the kids look on, bemused and delighted.

I imagine that something similar happened to countless aging Jewish salsa music freaks like myself when they saw the halftime show. I’m 75 now, and I got up and danced, remembering those years during Jimmy Carter’s presidency when I donned high heels and tight skirts to dance away my Saturdays nights at venues like Casino 14 — catorce, it was pronounced — on 14th Street right by Union Square. I’d had a Jewish boyfriend whose mom, a Bell telephone operator, had danced mambo in the 1950s and taught her son the moves. He taught me the cha-cha and rhumba; other friends my age, many of them Jews, loved the music too and knew the steps and clubbed along with me. All this seemed no more remarkable to us than knowing how to say the prayer over the bread on Friday nights.

The Jewish love affair with Latin music began back in the 1950s and, since then, Jews have played it as musicians, produced it as record company owners, and DJed it in clubs and on the radio. Scholars have tried to explain the affinity, and why it has been such a comfortable fit for both ethnic groups. Some speculate that the music of both cultures tends to minor scales. Others point out that, as Jewish neighborhoods such as East Harlem were transitioning in the 1950s to Puerto Rican enclaves, the two groups lived side by side. (Working-class Jews even shared factory spaces with Puerto Rican laborers, especially in the garment industry.)

And there was the Borscht Belt. Starting in the 1950s, the big hotels typically maintained two house bands: one for mainstream pop, and the other for all Latin — the tummlers taught mambo lessons around the swimming pool. By the 1930s, Puerto Rico had been thoroughly colonized by the U.S. and was thoroughly poverty stricken. A vast exit began to the mainland: Puerto Ricans, after all, were American citizens. Many moved to the Bronx. By the 1960s, many of the kids had grown up to be musicians. Some had big bands and a big-band sound. They played regular gigs at places like Kutscher’s in the Catskills. You can still hear Tito Puente in 1959 playing “Grossinger’s Cha Cha Cha.”

Some of the musicians were Jews — for example, Larry Harlow, a classically trained pianist whose grandfather was a cantor and father a Latin music bandleader in the Catskills. Harlow’s actual family name was Kahn; his nickname among musicians and audiences was “El Judio Maravilloso,” the Marvelous Jew. His cousin Lewis Kahn was a salsa violinist and trombonist who’d studied at Julliard; he was “El Segundo Judio Maravilloso.” Once, I gave Lewis a lift back to his hotel post-concert, after I saw him shambling down the street alone. Painfully shy and bespectacled, he seemed more like a member of the Frankfurt School than someone in a band with matching suits and screaming brass.

My foreign language in high school had been Spanish. My conversational skills were good but still stilted. I didn’t get better — didn’t pick up the rhythms and slang and everyday spoken beauty of the language until the 1970s. I began listening then, over and over and over, to my growing collection of LPs from the salsa label Fania, copying the words and learning how they mashed together. Based in New York City, Fania even had a fan magazine. New York also had the annual Puerto Rican parade, and I vividly recall running into impromptu conga circles on street corners, where young people sang not just in Spanish but also in Lucumi, the deeply spiritual language of the Afro-Caribbean Yoruba and Santeria religions. They’d picked up the words from the same records I listened to. Their devotion to the musical aspects of their heritage reminded me of my fascination with cantorial music, which was also available on vintage LPs and even on low-watt radio in Brooklyn.

Twenty-five years ago I went to Columbia one summer to study Yiddish. In class I learned that Molly Picon had sung in Yiddish in the 1940s on the Forward-owned radio station WEVD. Her show was followed by one in Spanish with mambo bands like La Sonora Matancera. How many Jews kept listening after the Picon program signed off? Were Sholem Aleichem and Uriel Weinreich the salseros of their own culture? I got bat mitzvahed at age 71 at a shul in Brooklyn. I had kosher food at the after-party. And we danced to a mambo band, led by Benjamin Lapidus, a fellow synagogue member.

Bad Bunny’s “Nueva Yol” couldn’t be more New York. It talks about going to Bear Mountain in the summer. About the Yankees and the Mets. The 4th of July. About Willie Colon, the beloved salsa trumpeter from the Bronx who ran (unsuccessfully) for Congress in 1994 and for Public Advocate in 2001.

Bad Bunny’s halftime performance of “Nueva Yol” also celebrated a Brooklyn matriarch named Maria Antonia Cay, aka Toñita. She runs an intimate social club for Puerto Ricans in Williamsburg where she cooks traditional food, serves it, and tends bar at age 85. She made a cameo appearance at halftime, as Bad Bunny sang lyrics about conflict and anxiety, featuring his signature tic, the phrase “Uuy, uuy!” Go forward in the mouth just a bit and you’re at Yiddish “Oy oy!” At one point he jumped into a joyful mosh pit of dancers. They hoisted him up and paraded him around. It could have been the reception, in any borough, of any Jewish wedding.

There’s a lot of talk these days about Diaspora Jews versus Israel Jews. It’s a topic that’s been fraught for years and inspires endless discussion. There’s not so much talk about Diaspora Puerto Ricans: the people who settled and struggled here decades ago and whose lives became cultural cross-over when Leonard Bernstein, Jerome Robbins and Leonard Bernstein — all Jews — created West Side Story. Today, the New York boroughs, with about a million Jews, constitute the biggest Jewish city in the world after Tel Aviv. And New York City has more Puerto Ricans than San Juan. Bad Bunny’s halftime show reminded us of our shared diaspora. It did so as our bodies grooved, even if they were geriatric bodies grooving slower than before.

The post Why Bad Bunny’s halftime show delighted New York Jews of a certain age appeared first on The Forward.