Local News

In Winnipeg, Everything’s “Coming up Roses”

Ed. note: Elsewhere on this website we have a story about Rabbi Carnie Rose having recently become the senior rabbi for Shaarey Zedek Congregation. At the time that story appeared, Gerry Posner was not aware that Myron would be doing a profile of Rabbi Carnie Rose, so he sent us his own story about the Rose family. But, in his own inimitable way, Gerry Posner tells the story of the Roses.

By GERRY POSNER With the recent arrival of Rabbi Carnie Rose to serve as senior rabbi for Shaarey Zedek Congregation and with his brother Kliel having served as spiritual leader of Etz Chayim Congregation since 2018, one should realize the full significance of having two brothers both serving as rabbis – for different congregations, in the same city.

You really have to go back 58 years ago – to the summer of 1967, when Rabbi Neal Rose and his wife Carol came to Winnipeg. Neal had come here to take a position in the Judaic Studies Department of the University of Manitoba (from 1967-2000).

Neal Rose had a tremendous impact upon the Winnipeg Jewish community – in the many roles he played. For instance, just ask anyone who was part of the alternative minyan which he led at the then Rosh Pina Synagogue during the High Holidays. You could also chat with anyone who was around during the 13 years when Rabbi Neal Rose served an an instructor in family therapy at the University of Winnipeg’s Department of Spiritual Care (from 2000-2013).

That was “Rose 1.0” (as in the Winnipeg Jets 1.0). As it turns out, Rabbi Neal and Carol are making a return engagement to Winnipeg (which I call “Rose 2.0”) to live here later this year – after some ten years living in St. Louis, Missouri, where Neal worked as a rabbinic scholar at Congregation B’Nai Amoona.

Now, with all of that said, one must not overlook the fact that the Roses and the rabbinate go beyond even sons Carnie and Kliel. Would you believe that the eldest son, Avi Rose, is a rabbi in Israel? Rabbi Avi Rose embraces what might be called the humanist aspect of Judaism. He is actively involved in leading life cycle events, teaching, assisting in rituals and indeed participating in Jewish calendar events. What Rabbi Avi Rose does is to focus on the person in his interaction with his congregants and fellow worshippers, inside and outside of the synagogue.

Then, there is Rabbi Or Rose. He is a rabbi, writer and social activist, and is the founding director of the Centre for Global Judaism at Boston’s Hebrew College. His writing skills likely emanate from his mother Carol, a well known poet. If going for 4 for 4 in the rabbinate for Neal and Carol was not enough of a rabbinical feat, add to that total the fact that daughter Adira is married to a rabbi, Michael Rose Knopf, the senior rabbi at Temple Beth-El in Stamford, Connecticut.

Of course, each of the Rose kids is a story. But one cannot just ignore the reality of the two Rose brothers holding leading rabbinic positions at the two largest synagogues in Winnipeg at the same moment in time. How did that come to pass? is the question congregants are lined up to discover – even if that means an early Shachrit service to get the answer.

Rabbi Kliel Rose has been at the helm of Congregation Etz Chayim since 2018. He returned to Winnipeg after a period of over 25 years away from this city. A graduate of the Jewish Theological Seminary, also a former spiritual leader in several congregations in the USA, then the rabbi at Beth Shalom Synagogue in Edmonton, the attraction for Rabbi Kliel Rose to come back to his roots in Winnipeg was palpable. After nearly seven years back with the congregation with which he grew up, he is conscious of the debt he owes to his parents, who were major role models for him. He is also aware of the relationships he developed in his growing-up years and the fact he was able to resume many of those connections so easily. During his time in the pulpit Rabbi Kliel has been honoured to receive a prestigious Human Rights Hero Award from “Truah: the Rabbinic Call for Human Rights.” Like his brother Carnie, Kliel is deeply involved in multifaith dialogue.

Kliel acknowledges the very unusual aspect of the two brothers working in the same city as rabbis of major congregations. He says that there was just no way for him to have imagined this scenario. He emphasizes the closeness he has with his older brother, referring to the fact that they often speak twice a day on matters rabbinical – or not. One of the comments Rabbi Kliel made about the future in Winnipeg with both Roses leading the way is that he sees this as a collaborative opportunity and not a competitive one. Interestingly, Rabbi Kliel Rose attributes his love of learning of Torah to his mother, who was his very first teacher. Kliel and wife Dorit Kosmin are the parents of five children. (Is there a future rabbi in the mix ?) He says that he benefitted from his parents in that they did not put any pressure on him or his siblings to enter the rabbinate. It just evolved.

Older brother Rabbi Carnie Shalom Rose, now 59, only recently conducted his very first Shabbat service at Shaarey Zedek. (I was there). He has had positions all over the world – in Canada, the USA, Israel, also the Far East, i.e., Japan, and Europe. Like Kliel, he was ordained at the Jewish Theological Seminary. He spent over 30 years in the rabbinical trenches. About 18 months ago he ventured into the Jewish organizational world when he assumed the role of President and CEO of the Mandel Jewish Community Centre in Cleveland, Ohio.

But, the pull to return to the synagogue and to Winnipeg was too great for Rabbi Carnie and his wife Paulie Zimnavoda Rose. After all, his whole career was centred in the synagogue. One aspect of Rabbi Carnie’s approach to his rabbinical duties is his emphasis on interfaith dialogue and relationships. He credits his parents for his firmly set belief in the importance of reaching out to the broader community. Most of all, he makes clear that it was Neal and Carol who nurtured his and indeed, all of the Rose family, with the love of Judaism. He, too, is amazed at the turn of events that has brought him and his brother together now. As Rabbi Carnie put it: “Winnipeg gave me grounding and an opportunity. I felt an obligation to return. I will gain if I can give back to those who gave to me.”

Carnie did return to live on Matheson Avenue, where he grew up, as he and Paulie took up residence in the south end of the city, closer to the Shaarey Zedek. The couple are the proud parents of four children, all of whom are now in their twenties, and all of whom are away at university, so Carnie and Paulie are now much sought after by Kliel and Dorit’s children – who finally have an aunt and uncle in the same city with them. Not so surprisingly, one of Carnie and Paulie Rose’s children, son Zakai, is preparing to follow in the family business, as he is a student at the Jewish Theological Seminary. Even the family of the legendary Gordie Howe of hockey fame could only produce two generations of NHL players.

What I came away with after talking to the two Rabbi Roses was first, how much they sounded like each other in voice; second, how close was their attachment to one another; and third, how much joy they anticipate working together from time to time in Winnipeg. At the time that I talked with both of them, for instance, they were excited about their plans to hold the first joint Tiisha B’Av service for Etz Chayim and Shaarey Zedek. They made me feel good about the future of Judaism in Winnipeg.

So what did the parents of these rabbis have to say? The patriarch of the family, Rabbi Neal Rose, was clear in attributing to his wife the fact that he and Carol have four sons who are rabbis and how it was that two of them ended up in the same city at the same time. He says that Carol had a huge influence on the children – right from an early age, in introducing the blessings and inculcating Jewish values. It was Carol, Neal says, who created an environment of learning which had such an impact on sons Carnie and Kliel. Her role in creating a Jewish home in Winnipeg for many years was instrumental in both Carnie and Kliel being open to returning to their original home of Winnipeg. True enough, the Rose boys both had a desire – in both their return engagements here, to serve as pulpit rabbis and, in doing so, to utilize one of their biggest assets: their strong interpersonal skills. Both are very comfortable in and enjoy that congregant to rabbi relationships -so critical in any successful synagogue.

As for the matriarch, Carol Rose, she agrees that this return to Winnipeg could not have been anticipated. She credits Winnipeg’s Jewish schooling and network of close friends for helping to secure a strong Jewish foundation for her sons. As she put it so succinctly, “The family had opportunities to grow up Jewishly.” With four sons now rabbis, and with their only daughter married to a rabbi, Carol clearly made an impact on her children. She admits that when she and Neal return this fall to Winnipeg, their biggest challenge will be to figure out which synagogue to attend each Shabbat. She also recognizes that even though Neal Rose has no plans to return to the pulpit, it is possible he might bless either or both congregations from time to time with his wisdom through occasional Divrei Torah or by teaching classes.

Some readers will recall the late Ethel Merman, who, without knowing it, foresaw this unusual moment in Winnipeg Jewish history appropriately in her song, “Everything’s coming up roses.”

Local News

Winnipeg Jewish Theatre breaks new ground with co-production with Rainbow Stage

By MYRON LOVE Winnipeg Jewish Theatre is breaking new ground with its first ever co-production with Rainbow Stage. The new partnership’s presentation of “Fiddler on the Roof” is scheduled to hit the stage at our city’s famed summer musical theatre venue in September 2026.

“We have collaborated with other theatre companies in joint productions before,” notes Dan Petrenko, the WJT’s artistic and managing director – citing previous partnerships with the Segal Centre for the Performing Arts in Montreal, the Harold Green Jewish Theatre in Toronto, Persephone Theatre in Saskatoon and Winnipeg’s own Dry Cold Productions. “Because of the times we’re living through, and particularly the growing antisemitism in our communities and across the country, I felt there is a need to tell a story that celebrates Jewish culture on the largest stage in the city – to reach as many people as possible.”

Last year, WJT approached Rainbow Stage with a proposal for the co-presentation of “Fiddler on the Roof.” Rainbow Stage management was really enthusiastic in their response, Petrenko reports.

“We are excited to be working with Winnipeg’s largest musical theatre company,” he notes. “Rainbow Stage has an audience of more than 10,000 people every season. Fiddler is a great, family-oriented story and, through our joint effort with Rainbow Stage, WJT will be able to reach out to new and younger audiences.”

“We are also working to welcome more diverse audiences from other communities, as well as newcomers – families who have moved here from Israel, Argentina and countries of the former Soviet Union.”

Helping Petrenko to achieve those goals are two relatively new and younger additions to WJT’s management team. Both Company Manager Etel Shevelev, and Head of Marketing Julia Kroft are in their 20s – as is Petrenko himself.

Kroft, who is also Gray Academy’s Associate Director of Advancement and Alumni Relations, needs little or no introduction to many readers. In addition to her work for Gray Academy and WJT, the daughter of David and Ellen Kroft has been building a second career as a singer and actor. Over the past few years, she has performed by herself or as part of a musical ensemble at Jewish community events, as well as in various professional theatre productions in the city.

Etel Shevelev is also engaged in a dual career. In addition to working full time at WJT, she is also a Fine Arts student (majoring in graphic design) at the University of Manitoba. Outside of school, she is an interdisciplinary visual artist (exhibiting her work and running workshops), so you can say the art world is no stranger to her.

(She will be partcipating in Limmud next month as a member of the Rimon Art Collective.)

Shevelev grew up in Kfar Saba (northeast of Tel Aviv). She reports that in Israel she was involved in theatre from a young age. “In 2019, I graduated from a youth theatre school, which I attended for 11 years.” In a sense, her work for WJT brings her full circle.

She arrived in Winnipeg just six years ago with her parents. “I was 19 at the time,” she says.

After just a year in Winnipeg, her family decided to relocate to Ottawa, while she chose to stay here. “I was already enrolled in university, had a long-term partner, and a job,” she explains. “I felt that I was putting down roots in Winnipeg.”

Etel expects to graduate by the end of the academic year, allowing her to focus on the arts professionally full-time.

In her role as company manager, Shevelev notes, she is responsible for communications with donors, contractors, and unions, as well as applying for various grants and funding opportunities.

In addition, her linguistic skills were put to use last spring for WJT’s production of “The Band’s Visit,” a story about an Egyptian band that was invited to perform at a cultural centre opening ceremony in the lively centre of Israel, but ended up in the wrong place – a tiny, communal town in southern Israel. Shevelev was called on to help some of the performers with the pronunciation of Hebrew words and with developing a Hebrew accent.

“I love working for WJT,” she enthuses. “Every day is different.”

Shevelev and Petrenko are also enthusiastic about WJT’s next production – coming up in April: “Ride: The Musical” debuted in London’s West End three years ago, and then went on to play at San Diego’s Old Globe theatre to rave reviews. The WJT production will be the Canadian premiere!

The play, Petrenko says, is based on the true story of Annie Londonderry, a young woman – originally from Latvia, who, in 1894, beat all odds and became the first woman to circle the world on a bicycle.

Petrenko is also happy to announce that the director and choreographer for the production will be Lisa Stevens – an Emmy Award nominee and Olivier Award winner. (The Olivier is presented annually by the Society of London Theatre to recognize excellence in professional London theatre).

“Lisa is in great demand across Canada, and the world really,” the WJT artistic director says. “I am so thrilled that we will be welcoming one of the greatest Jewish directors and choreographers of our time to Winnipeg this Spring.”

For more information about upcoming WJT shows, readers can visit wjt.ca, email the WJT office at info@wjt.ca or phone the box office at 204-477-7515.

Local News

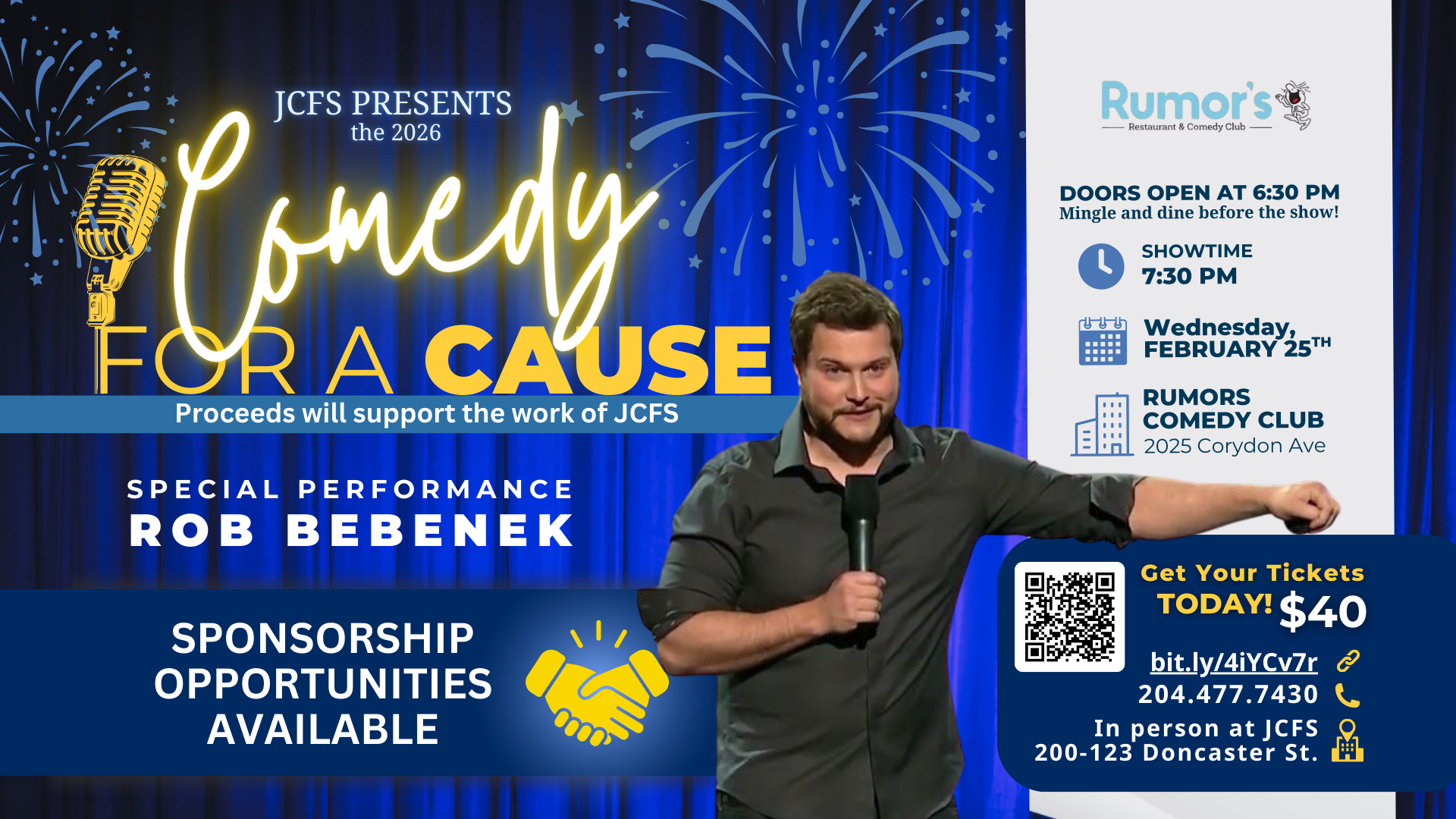

Rising Canadian comedy star Rob Bebenek to headline JCFS’ second annual “Comedy for a Cause”

By MYRON LOVE Last year, faced with a federal government budget cut to its Older Adult Services programs, Jewish Child and Family Service launched a new fundraising initiative. “Comedy with a Cause” was held at Rumor’s Comedy club and featured veteran Canadian stand-up comic Dave Hemstad.

That evening was so successful that – by popular demand – JCFS is doing an encore. “We were blown away by the support from the community,” says Al Benarroch, JCFS’s president and CEO.

“This is really a great way to support JCFS by being together and having fun,” he says.

“Last year, JCFS was able to sell-out the 170 tickets it was allotted by Rumor’s,” adds Alexis Wenzowski, JCFS’s COO. “There were also general public attendees at the event last year. Participants enjoyed a fun evening, complete with a 50/50 draw and raffle. We were incredibly grateful for those who turned out, the donors for the raffle baskets, and of course, Rumor’s Comedy Club.

“Feedback was very positive about it being an initiative that encouraged people to have fun for a good cause: our Older Adult Services Team.”

This year’s “Comedy for a Cause” evening is scheduled for Wednesday, February 25. Wenzowski reports that this year’s featured performer, Rob Bebenek, first made a splash on the Canadian comedy scene at the 2018 Winnipeg Comedy festival. He has toured extensively throughout North America, appearing in theatres, clubs and festivals. He has also made several appearances on MTV as well as opening shows for more established comics, such as Gerry Dee and the late Bob Saget.

For the 2026 show, Wenzowski notes, Rumors’ is allotting JCFS 200 tickets. As with last year, there will also be some raffle baskets and a 50/50 draw.

“Our presenting sponsors for the evening,” she reports, “are the Vickar Automotive Group and Kay Four Properties Incorporated.”

The funds raised from this year’s comedy evening are being designated for the JCFS Settlement and Integration Services Department. “JCFS chose to do this because of our reduction in funding last year by the federal government to this department,” Wenzowski points out.

“Last year alone,” she reports, “our Settlement and Integration Services team settled 118 newcomer families – from places like Israel, Mexico, Brazil, and Argentina. Each year, our program supports even more newcomer families with things like case management, supportive counselling, employment coaching, workshops, programming for newcomer seniors, and more.”

“We hope to raise more than $15,000 through this event for our Settlement and Integration Program,” Al Benarroch adds. “The team does fantastic work, and we know that our newcomer Jewish families need the supports from JCFS. I want to thank our sponsors, Rumor’s Comedy Club, and attendees for supporting us.”

Tickets for the show cost $40 and are available to purchase by calling JCFS (204-477-7430) or by visiting here: https://www.zeffy.com/en-CA/ticketing/jcfs-comedy-for-a-cause. Sponsorships are still available.

Local News

Ninth Shabbat Unplugged highlight of busy year for Winnipeg Hillel

By MYRON LOVE Lindsay Kerr, Winnipeg’s Hillel director, is happy to report that this year’s ninth Shabbat UnPlugged, held on the weekend of January 9-11, attracted approximately 90 students from 11 different universities, including 20 students who were from out of town.

Shabbat UnPlugged was started in 2016 by (now-retired) Dr. Sheppy Coodin, who was a science teacher at Gray Academy, along with fellow Gray Academy teacher Avi Posen (who made aliyah in 2019) – building on the Shabbatons that Gray Academy had been organizing for the school’s high school students for many years.

The inaugural Shabbat UnPlugged was so successful that Coodin and Posen did it again in 2017 and took things one step further by combining their Shabbat UnPlugged with Hillel’s annual Shabbat Shabang Shabbaton that brings together Jewish university students from Winnipeg and other Jewish university students from Western Canada.

As in the past, this year’s Shabbat UnPlugged weekend was held at Lakeview’s Hecla Resort. “What we like about Hecla,” Kerr notes, “is that they let us bring in our own kosher food, it is out of the city and close to nature for those who want to enjoy the outdoors.”

The weekend retreat traditionally begins with a candle lighting, kiddush and a traditional Shabbat supper. Unlike previous Shabbats UnPlugged, Kerr points out, there were no outside featured speakers this year. All religious services and activities were led by students or national program partners.

The weekend was funded in part by grants from CJPAC and StandWithUs Canada, along with the primary gift from The Asper Foundation.

Kerr reports that the activities began with 18 of our local Jewish university students participating in a new student Shabbaton – inspired by Shabbat Unplugged, titled “Roots & Rising.”

In addition to Shabbat Unplugged, Hillel further partnered with Chabad for a Sukkot program in the fall, as well as with Shaarey Zedek Congregation and StandWithUs Canada for a Chanukah program. Hillell also featured a commemoration of October 7, an evening of laser tag and, in January, a Hillel-led afternoon of ice skating.

Coming up this month will be a visit to an Escape Room – and a traditional Shabbat dinner in March.

Kerr estimates that there are about 300 Jewish students at the University of Manitoba and 100 at the University of Winnipeg.

“Our goal is to attract more Jewish students to take part in our programs and connect with our community,” she comments.