Local News

Palestinian campus encampments dismantled across Canada—whether voluntarily or by authorities

By SAM MARGOLIS (Canadian Jewish News) Several encampments which have occupied Canadian universities since April have been dismantled, a week after an Ontario Supreme Court granted the University of Toronto an injunction to remove a pro-Palestinian tent protest from its downtown campus.

At McGill, the Montreal campus was closed for the day from the early hours of June 10 while police and a private security firm removed protesters.

“McGill will always support the right to free expression and assembly, within the bounds of the laws and policies that keep us all safe. However, recent events go far beyond peaceful protest, and have inhibited the respectful exchange of views and ideas that is so essential to the University’s mission and to our sense of community,” McGill president Deep Saini said in a news release.

“People linked to the camp have harassed our community members, engaged in antisemitic intimidation, damaged and destroyed McGill property, forcefully occupied a building, clashed with police, and committed acts of assault,” he said.

In Ottawa, protesters voluntarily removed their tents from the campus July 10, claiming that negotiations with the university administration had stalled.

Several encampments which have occupied Canadian universities since April have been dismantled, a week after an Ontario Supreme Court granted the University of Toronto an injunction to remove a pro-Palestinian tent protest from its downtown campus.

At McGill, the Montreal campus was closed for the day from the early hours of June 10 while police and a private security firm removed protesters.

“McGill will always support the right to free expression and assembly, within the bounds of the laws and policies that keep us all safe. However, recent events go far beyond peaceful protest, and have inhibited the respectful exchange of views and ideas that is so essential to the University’s mission and to our sense of community,” McGill president Deep Saini said in a news release.

“People linked to the camp have harassed our community members, engaged in antisemitic intimidation, damaged and destroyed McGill property, forcefully occupied a building, clashed with police, and committed acts of assault,” he said.

In Ottawa, protesters voluntarily removed their tents from the campus July 10, claiming that negotiations with the university administration had stalled.

“Every dollar you make off the blood of Palestinians will be lost as we continue to confront you, on this lawn and across campus this coming year, and the year after that, and every year until the complete liberation of Palestine, from the river to the sea,” protesters from Occupy Tabaret said on a post on Instagram.

An encampment at University of Waterloo was dismantled on July 7, in exchange for the university dropping a $1.5-million lawsuit and injunction proceedings.

A pro-Palestinian encampment at the University of British Columbia, which had maintained an inescapable presence at the Vancouver campus since the end of April, was voluntarily dismantled on the evening of July 7—and local Jewish groups are hoping this will provide a step towards easing fears among Jewish students and the community as a whole.

Several encampments which have occupied Canadian universities since April have been dismantled, a week after an Ontario Supreme Court granted the University of Toronto an injunction to remove a pro-Palestinian tent protest from its downtown campus.

At McGill, the Montreal campus was closed for the day from the early hours of June 10 while police and a private security firm removed protesters.

“McGill will always support the right to free expression and assembly, within the bounds of the laws and policies that keep us all safe. However, recent events go far beyond peaceful protest, and have inhibited the respectful exchange of views and ideas that is so essential to the University’s mission and to our sense of community,” McGill president Deep Saini said in a news release.

“People linked to the camp have harassed our community members, engaged in antisemitic intimidation, damaged and destroyed McGill property, forcefully occupied a building, clashed with police, and committed acts of assault,” he said.

In Ottawa, protesters voluntarily removed their tents from the campus July 10, claiming that negotiations with the university administration had stalled.

“Every dollar you make off the blood of Palestinians will be lost as we continue to confront you, on this lawn and across campus this coming year, and the year after that, and every year until the complete liberation of Palestine, from the river to the sea,” protesters from Occupy Tabaret said on a post on Instagram.

An encampment at University of Waterloo was dismantled on July 7, in exchange for the university dropping a $1.5-million lawsuit and injunction proceedings.

A pro-Palestinian encampment at the University of British Columbia, which had maintained an inescapable presence at the Vancouver campus since the end of April, was voluntarily dismantled on the evening of July 7—and local Jewish groups are hoping this will provide a step towards easing fears among Jewish students and the community as a whole.

The closure of the UBC Vancouver encampment took place a week after the Ontario Superior Court of Justice granted the University of Toronto an injunction to clear a pro-Palestinian encampment from its campus. The court ordered tents to be removed and gave police authority to arrest anyone who did not vacate the protest site.

“In our society, we have decided that the owner of property generally gets to decide what happens on the property,” Justice Markus Koehnen wrote in the July 2 ruling.

“If the protesters can take that power for themselves by seizing Front Campus, there is nothing to stop a stronger group from coming and taking the space over from the current protesters. That leads to chaos. Society needs an orderly way of addressing competing demands on space. The system we have agreed to is that the owner gets to decide how to use the space.”

Students at UofT voluntarily dismantled the encampment, which had numbered over 150 tents at some points, before the injunction deadline.

In Vancouver, Michael Sachs, the executive director of the Jewish National Fund Pacific, told The CJN, “There is a sense of relief that this is over, but also a sense of frustration with the amount of damage this has done, both to the Jewish community on campus and to the campus itself,”

Sachs went to UBC early Monday morning and took a photo of himself before the emptied encampment that he later posted on social media.

Several encampments which have occupied Canadian universities since April have been dismantled, a week after an Ontario Supreme Court granted the University of Toronto an injunction to remove a pro-Palestinian tent protest from its downtown campus.

At McGill, the Montreal campus was closed for the day from the early hours of June 10 while police and a private security firm removed protesters.

“McGill will always support the right to free expression and assembly, within the bounds of the laws and policies that keep us all safe. However, recent events go far beyond peaceful protest, and have inhibited the respectful exchange of views and ideas that is so essential to the University’s mission and to our sense of community,” McGill president Deep Saini said in a news release.

“People linked to the camp have harassed our community members, engaged in antisemitic intimidation, damaged and destroyed McGill property, forcefully occupied a building, clashed with police, and committed acts of assault,” he said.

In Ottawa, protesters voluntarily removed their tents from the campus July 10, claiming that negotiations with the university administration had stalled.

“Every dollar you make off the blood of Palestinians will be lost as we continue to confront you, on this lawn and across campus this coming year, and the year after that, and every year until the complete liberation of Palestine, from the river to the sea,” protesters from Occupy Tabaret said on a post on Instagram.

An encampment at University of Waterloo was dismantled on July 7, in exchange for the university dropping a $1.5-million lawsuit and injunction proceedings.

A pro-Palestinian encampment at the University of British Columbia, which had maintained an inescapable presence at the Vancouver campus since the end of April, was voluntarily dismantled on the evening of July 7—and local Jewish groups are hoping this will provide a step towards easing fears among Jewish students and the community as a whole.

The closure of the UBC Vancouver encampment took place a week after the Ontario Superior Court of Justice granted the University of Toronto an injunction to clear a pro-Palestinian encampment from its campus. The court ordered tents to be removed and gave police authority to arrest anyone who did not vacate the protest site.

“In our society, we have decided that the owner of property generally gets to decide what happens on the property,” Justice Markus Koehnen wrote in the July 2 ruling.

“If the protesters can take that power for themselves by seizing Front Campus, there is nothing to stop a stronger group from coming and taking the space over from the current protesters. That leads to chaos. Society needs an orderly way of addressing competing demands on space. The system we have agreed to is that the owner gets to decide how to use the space.”

Students at UofT voluntarily dismantled the encampment, which had numbered over 150 tents at some points, before the injunction deadline.

In Vancouver, Michael Sachs, the executive director of the Jewish National Fund Pacific, told The CJN, “There is a sense of relief that this is over, but also a sense of frustration with the amount of damage this has done, both to the Jewish community on campus and to the campus itself,”

Sachs went to UBC early Monday morning and took a photo of himself before the emptied encampment that he later posted on social media.

“Once the encampment was no longer in the news cycle, it was taken down. Some questions now are, who is going to pay for the damage done? And how much is it all going to cost after they destroyed the field?”

At various points during the 69-day encampment, dozens of tents and hundreds of pro-Palestinian protesters took part in the event, which occupied MacInnes Field at the school’s Vancouver campus. Some local media outlets described the atmosphere as resembling a festival. In ordinary times, the field is a campus hub and green space used by the university’s community for numerous recreational activities. Today it remains fenced and barricaded.

Sachs had made regular trips to the perimeter of the protest since it began over 10 weeks ago. On its first day, according to his account, he witnessed Charlotte Kates, the coordinator of Samidoun, helping to organize and orchestrate the encampment.

Several encampments which have occupied Canadian universities since April have been dismantled, a week after an Ontario Supreme Court granted the University of Toronto an injunction to remove a pro-Palestinian tent protest from its downtown campus.

At McGill, the Montreal campus was closed for the day from the early hours of June 10 while police and a private security firm removed protesters.

“McGill will always support the right to free expression and assembly, within the bounds of the laws and policies that keep us all safe. However, recent events go far beyond peaceful protest, and have inhibited the respectful exchange of views and ideas that is so essential to the University’s mission and to our sense of community,” McGill president Deep Saini said in a news release.

“People linked to the camp have harassed our community members, engaged in antisemitic intimidation, damaged and destroyed McGill property, forcefully occupied a building, clashed with police, and committed acts of assault,” he said.

In Ottawa, protesters voluntarily removed their tents from the campus July 10, claiming that negotiations with the university administration had stalled.

“Every dollar you make off the blood of Palestinians will be lost as we continue to confront you, on this lawn and across campus this coming year, and the year after that, and every year until the complete liberation of Palestine, from the river to the sea,” protesters from Occupy Tabaret said on a post on Instagram.

An encampment at University of Waterloo was dismantled on July 7, in exchange for the university dropping a $1.5-million lawsuit and injunction proceedings.

A pro-Palestinian encampment at the University of British Columbia, which had maintained an inescapable presence at the Vancouver campus since the end of April, was voluntarily dismantled on the evening of July 7—and local Jewish groups are hoping this will provide a step towards easing fears among Jewish students and the community as a whole.

The closure of the UBC Vancouver encampment took place a week after the Ontario Superior Court of Justice granted the University of Toronto an injunction to clear a pro-Palestinian encampment from its campus. The court ordered tents to be removed and gave police authority to arrest anyone who did not vacate the protest site.

“In our society, we have decided that the owner of property generally gets to decide what happens on the property,” Justice Markus Koehnen wrote in the July 2 ruling.

“If the protesters can take that power for themselves by seizing Front Campus, there is nothing to stop a stronger group from coming and taking the space over from the current protesters. That leads to chaos. Society needs an orderly way of addressing competing demands on space. The system we have agreed to is that the owner gets to decide how to use the space.”

Students at UofT voluntarily dismantled the encampment, which had numbered over 150 tents at some points, before the injunction deadline.

In Vancouver, Michael Sachs, the executive director of the Jewish National Fund Pacific, told The CJN, “There is a sense of relief that this is over, but also a sense of frustration with the amount of damage this has done, both to the Jewish community on campus and to the campus itself,”

Sachs went to UBC early Monday morning and took a photo of himself before the emptied encampment that he later posted on social media.

“Once the encampment was no longer in the news cycle, it was taken down. Some questions now are, who is going to pay for the damage done? And how much is it all going to cost after they destroyed the field?”

At various points during the 69-day encampment, dozens of tents and hundreds of pro-Palestinian protesters took part in the event, which occupied MacInnes Field at the school’s Vancouver campus. Some local media outlets described the atmosphere as resembling a festival. In ordinary times, the field is a campus hub and green space used by the university’s community for numerous recreational activities. Today it remains fenced and barricaded.

Sachs had made regular trips to the perimeter of the protest since it began over 10 weeks ago. On its first day, according to his account, he witnessed Charlotte Kates, the coordinator of Samidoun, helping to organize and orchestrate the encampment.

The Centre of Israel and Jewish Affairs (CIJA) has long called for Samidoun to be added to Canada’s list of terrorist organizations. CIJA and others maintain that the Vancouver-based organization has direct ties to the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), which, since 2003, has been listed as a terrorist group under Canada’s Criminal Code.

On May 1, Vancouver police started a hate crime investigation after comments Kates made at a rally praising the Oct. 7 Hamas attacks on Israel and referring to a number of terrorist groups as heroes.

Sachs also noted that UBC is located in the riding of British Columbia Premier David Eby. He believes that Eby, as well as the university, could have done more to end the encampment sooner and help assuage the emotional distress it has caused for Jewish students, staff and faculty.

Nico Slobinsky, CIJA’s vice-president of the Pacific Region, said he was encouraged to see the encampment abandoned and the return of MacInnes Field for all students to enjoy safely.

“Since the Oct. 7 terrorist attacks committed by Hamas, Jewish communities have come under increased pressure in many spaces across Canada and around the world, including in post-secondary education. The UBC encampment was concerning and made many Jewish students feel unsafe on their own campus,” he said.

Ohad Gavrieli, the incoming executive director of Hillel BC, sent a note to the Jewish community on campus this week stating that the encampment, had been, since it started on April 29, a “troubling center of antisemitism and anti-Israel activities.” He expressed concern that “such a demonstration of hate and intimidation was allowed to persist at the heart of UBC.”

“As we look ahead to the fall semester in September, we hope that the lessons learned from this troubling episode will lead to a campus environment where Jewish students can feel safe and respected,” Gavrieli wrote.

The university, at this time, offered no response regarding any possible legal actions that may be pursued against the organizers of the encampment. Further, it is unclear when the field will be returned to its earlier condition and how much it will cost to repair it.

Clare Hamilton-Eddy, the director of media relations at UBC, did tell The CJN that the school “remains committed to respectful dialogue with student protesters.”

A group calling itself the People’s University of Gaza UBC, which, among its other demands, has called on UBC to divest from Israel, vowed that it would continue to protest.

Several encampments which have occupied Canadian universities since April have been dismantled, a week after an Ontario Supreme Court granted the University of Toronto an injunction to remove a pro-Palestinian tent protest from its downtown campus.

At McGill, the Montreal campus was closed for the day from the early hours of June 10 while police and a private security firm removed protesters.

“McGill will always support the right to free expression and assembly, within the bounds of the laws and policies that keep us all safe. However, recent events go far beyond peaceful protest, and have inhibited the respectful exchange of views and ideas that is so essential to the University’s mission and to our sense of community,” McGill president Deep Saini said in a news release.

“People linked to the camp have harassed our community members, engaged in antisemitic intimidation, damaged and destroyed McGill property, forcefully occupied a building, clashed with police, and committed acts of assault,” he said.

In Ottawa, protesters voluntarily removed their tents from the campus July 10, claiming that negotiations with the university administration had stalled.

“Every dollar you make off the blood of Palestinians will be lost as we continue to confront you, on this lawn and across campus this coming year, and the year after that, and every year until the complete liberation of Palestine, from the river to the sea,” protesters from Occupy Tabaret said on a post on Instagram.

An encampment at University of Waterloo was dismantled on July 7, in exchange for the university dropping a $1.5-million lawsuit and injunction proceedings.

A pro-Palestinian encampment at the University of British Columbia, which had maintained an inescapable presence at the Vancouver campus since the end of April, was voluntarily dismantled on the evening of July 7—and local Jewish groups are hoping this will provide a step towards easing fears among Jewish students and the community as a whole.

The closure of the UBC Vancouver encampment took place a week after the Ontario Superior Court of Justice granted the University of Toronto an injunction to clear a pro-Palestinian encampment from its campus. The court ordered tents to be removed and gave police authority to arrest anyone who did not vacate the protest site.

“In our society, we have decided that the owner of property generally gets to decide what happens on the property,” Justice Markus Koehnen wrote in the July 2 ruling.

“If the protesters can take that power for themselves by seizing Front Campus, there is nothing to stop a stronger group from coming and taking the space over from the current protesters. That leads to chaos. Society needs an orderly way of addressing competing demands on space. The system we have agreed to is that the owner gets to decide how to use the space.”

Students at UofT voluntarily dismantled the encampment, which had numbered over 150 tents at some points, before the injunction deadline.

In Vancouver, Michael Sachs, the executive director of the Jewish National Fund Pacific, told The CJN, “There is a sense of relief that this is over, but also a sense of frustration with the amount of damage this has done, both to the Jewish community on campus and to the campus itself,”

Sachs went to UBC early Monday morning and took a photo of himself before the emptied encampment that he later posted on social media.

“Once the encampment was no longer in the news cycle, it was taken down. Some questions now are, who is going to pay for the damage done? And how much is it all going to cost after they destroyed the field?”

At various points during the 69-day encampment, dozens of tents and hundreds of pro-Palestinian protesters took part in the event, which occupied MacInnes Field at the school’s Vancouver campus. Some local media outlets described the atmosphere as resembling a festival. In ordinary times, the field is a campus hub and green space used by the university’s community for numerous recreational activities. Today it remains fenced and barricaded.

Sachs had made regular trips to the perimeter of the protest since it began over 10 weeks ago. On its first day, according to his account, he witnessed Charlotte Kates, the coordinator of Samidoun, helping to organize and orchestrate the encampment.

The Centre of Israel and Jewish Affairs (CIJA) has long called for Samidoun to be added to Canada’s list of terrorist organizations. CIJA and others maintain that the Vancouver-based organization has direct ties to the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), which, since 2003, has been listed as a terrorist group under Canada’s Criminal Code.

On May 1, Vancouver police started a hate crime investigation after comments Kates made at a rally praising the Oct. 7 Hamas attacks on Israel and referring to a number of terrorist groups as heroes.

Sachs also noted that UBC is located in the riding of British Columbia Premier David Eby. He believes that Eby, as well as the university, could have done more to end the encampment sooner and help assuage the emotional distress it has caused for Jewish students, staff and faculty.

Nico Slobinsky, CIJA’s vice-president of the Pacific Region, said he was encouraged to see the encampment abandoned and the return of MacInnes Field for all students to enjoy safely.

“Since the Oct. 7 terrorist attacks committed by Hamas, Jewish communities have come under increased pressure in many spaces across Canada and around the world, including in post-secondary education. The UBC encampment was concerning and made many Jewish students feel unsafe on their own campus,” he said.

Ohad Gavrieli, the incoming executive director of Hillel BC, sent a note to the Jewish community on campus this week stating that the encampment, had been, since it started on April 29, a “troubling center of antisemitism and anti-Israel activities.” He expressed concern that “such a demonstration of hate and intimidation was allowed to persist at the heart of UBC.”

“As we look ahead to the fall semester in September, we hope that the lessons learned from this troubling episode will lead to a campus environment where Jewish students can feel safe and respected,” Gavrieli wrote.

The university, at this time, offered no response regarding any possible legal actions that may be pursued against the organizers of the encampment. Further, it is unclear when the field will be returned to its earlier condition and how much it will cost to repair it.

Clare Hamilton-Eddy, the director of media relations at UBC, did tell The CJN that the school “remains committed to respectful dialogue with student protesters.”

A group calling itself the People’s University of Gaza UBC, which, among its other demands, has called on UBC to divest from Israel, vowed that it would continue to protest.

In a statement released on social media, the group said, “After years of divestment organizing on campus, we build the People’s University of Gaza as one tactic of escalation. We call on you to join us as we advance into the next stage of our strategy for our demands.”

Encampments have been prevalent on prominent university campuses in BC for the past several weeks. Protesters started a camp on the University of Victoria campus on May 1 and, according to university officials, the size of the encampment has not diminished.

“The university continues to take a calm and thoughtful approach and remains hopeful for a peaceful resolution.” said Kristi Simpson, vice-president of finance and operations at UVic.

Meanwhile, at the Vancouver Island University campus in Nanaimo, protesters continue to disrupt activities on the campus. On June 28, a group of 25 protesters occupied a building, interrupting an ongoing exam, blockading several entry doors, and causing damage to flags in the school’s International Centre. Over the June 29-30 weekend, protesters vandalized the entry to VIU’s human resources office.

“Such actions, which violate university policies, jeopardize the safety and security of our staff, infringe upon private and secure areas, and cannot be tolerated. We firmly condemn the disruption of academic exams, as our primary mission is to provide an optimal learning experience for our students,” officials from VIU said in a July 3 statement.

An encampment at UBC’s campus in Kelowna ended on June 29.

Local News

Thank you to the community from the Chesed Shel Emes

We’re delighted to share a major milestone in our Capital Campaign, “Building on our Tradition.” Launched in November 2018, this campaign aimed to replace our outdated facility with a modern space tailored to our unique needs. Our new building is designed with ritual at its core, featuring ample preparation space, Shomer space, and storage, creating a warm and welcoming environment for our community during times of need.

We’re grateful to the nearly 1,000 generous donors who contributed over $4 million towards our new facility. A $750,000 mortgage will be retired in November 2025, completing this monumental project in just seven years.

We’re also thrilled to announce that our Chesed Shel Emes Endowment Fund has grown tenfold, from $15,000 to $150,000, thanks to you, the Jewish Foundation of Manitoba’s FundMatch program, and Million Dollar Match initiative in 2024. Our fund helps ensure that everyone can have a dignified Jewish funeral regardless of financial need.

As we look to the future, our goal remains to ensure the Chevra Kadisha continues to serve our community for generations to come. Our focus now shifts to replenishing our savings account and growing our JFM Endowment fund.

We’re deeply grateful for your support over the past several years.

It’s our privilege to serve our community with care and compassion.

With sincere appreciation,

Campaign cabinet: Hillel Kravetsky, Gerry Pritchard, Stuart Pudavick,

Jack Solomon, and Rena Boroditsky

Murray S. Greenfield, President

Local News

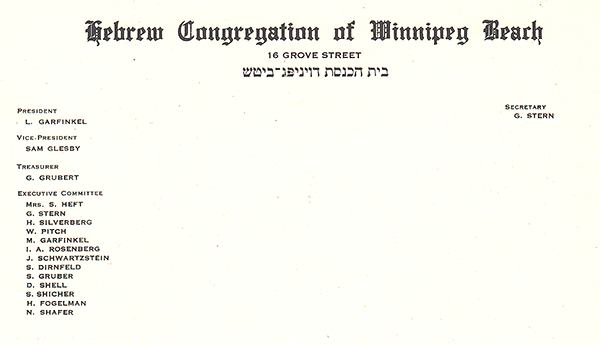

Winnipeg Beach Synagogue about to celebrate 75th anniversary

By BERNIE BELLAN (July 13) In 1950 a group of cottage owners at Winnipeg Beach took it upon themselves to relocate a one-room schoolhouse that was in the Beausejour area to Winnipeg Beach where it became the beach synagogue at the corner of Hazel and Grove.

There it stayed until 1998 when it was moved to its current location at Camp Massad.

On August 2nd members of the synagogue will be holding a 75th anniversary celebration.

As part of the celebration anyone who is a descendant or relative of any of the original members of the first executive committee (as seen in the photo here) is invited to attend the synagogue that morning.

If you are a relative please contact Abe Borzykowski at wpgbeachshule@shaw.ca or aborzykowski@shaw.ca to let Abe know you might be attending or for more information about the 75th anniversary celebration.

We will soon be publishing a story about the history of the beach synagogue, which is something I’ve been writing about for over 25 years.

Local News

Vickar Family cuts ribbon on new Tova Vickar and Family Childcare Centre

By MYRON LOVE In the words of Larry Vickar, the Shaarey Zedek’s successful Dor V’ Dor Campaign “is not only a renewal of the synagogue but truly a renewal movement of Jewish life in our community.”An integral part of that renewal movement was the creation of a daycare centre within the expanded synagogue. On Monday, June 23, Larry and Tova Vickar cut the ribbon, thereby officially opening the Tova Vickar and Family Childcare Centre in the presence of 100 of their family members, friends and other supporters of the project.

The short program preceding the morning ribbon-cutting began with a continental breakfast followed by a welcome by both Fanny Levy, Shaarey Zedek’s Board President, and Executive Director Dr. Rena Secter Elbaze. In Elbaze’s remarks, she noted that Larry and Tova wanted their family (including son Stephen and family, who flew in from Florida) and friends at the event to celebrate the opening of the Tova Vickar and Family Childcare Centre, “not because of the accolades, but because, as Larry put it, he hopes that their investment in the congregation will inspire others to do the same.”

“When Larry and I spoke about what this gift meant to him and the message he wanted people to take away,” she continued, “I couldn’t help but connect it to the teachings of Reb Zalman Schachter-Shalomi whose book – Age-ing to Sage-ing – changes the whole way we look at the concept of ageing and basing it on our ancestral teachings.”

She explained that his concept of “Sage-ing” is based on three key ideas – Discover your meaning and purpose; accept our mortality and think about the legacy you want to leave.

“Larry spoke about these exact concepts when we met,” she said.

Elbaze also noted the presence of Shaarey Zedek’s newly-arrived senior Rabbi Carnie Rose, former Rabbi Alan Green, and area MLAs Mike Moroz and Carla Compton.

Larry Vickar expressed his great appreciation for all those in attendance. “Tova and I are deeply moved to stand here with you today for this important milestone in our community”, he said. “We are grateful to be surrounded by all of you, the people we care about, our family and friends… you who have touched our lives and played some part in our journey.”