Local News

Simkin Centre shows accumulated deficit of $779,426 for year end March 31, 2025 – but most personal care homes in Winnipeg are struggling to fund daily operations

By BERNIE BELLAN The last (November 20) issue of the Jewish Post had as an insert a regular publication of the Simkin Centre called the “Simkin Star.”

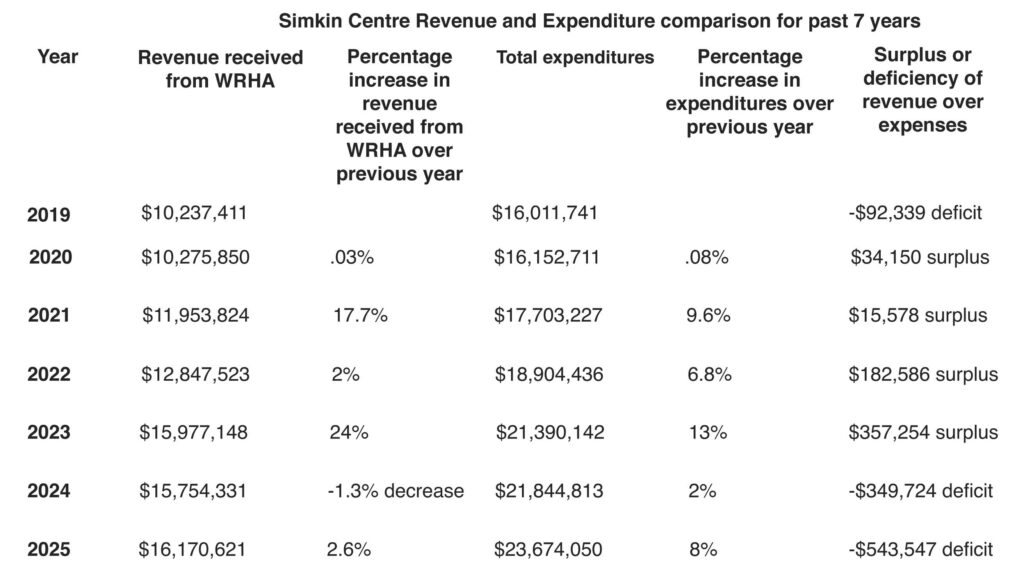

Looking through the 16 pages of the Simkin Star I noticed that three full pages were devoted to financial information about the Simkin Centre, including the financial statement for the most recent fiscal year (which ended March 31, 2025). I was rather shocked to see that Simkin had posted a deficit of $406,974 in 2025, and this was on top of a deficit of $316,964 in 2024.

In the past month, I had also been looking at financial statements for the Simkin Centre going back to 2019. I had seen that Simkin had been running surpluses for four straight years – even through Covid.

But seeing the most recent deficit led me to wonder: Is the Simkin Centre’s situation unusual in its having run quite large deficits the past two years? I know that, in speaking with Laurie Cerqueti, CEO of the Simkin Centre, over the years, that she had often complained that not only Simkin, but many other personal care homes do not receive sufficient funding from the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority.

At the same time, an article I had read by Free Press Faith writer John Longhurst, and which was published in the August 5, 2025 issue of the Free Press had been sticking in my brain because what Longhurst wrote about the lack of funding increases by the WRHA for food costs in personal care homes deeply troubled me.

Titled “Driven by faith, frustrated by funding,” Longhurst looked at how three different faith-based personal care homes in Winnipeg have dealt with the ever increasing cost of food.

One sentence in that article really caught my attention, however, when Longhurst wrote that the “provincial government, through the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority, has not increased the amount of funding it provides for care-home residents in Manitoba since 2009.”

Really? I wondered. Is that true?

As a result, I began a quest to try and ascertain whether what Longhurst claimed was the case was actually the case.

For the purpose of this article, personal care homes will be referred to as PCHs.

During the course of my gathering material for this article I contacted a number of different individuals, including: Laurie Cerqueti, CEO of the Simkin Centre; the CEO of another personal care home who wished to remain anonymous; Gladys Hrabi, who wears many hats, among them CEO of Manitoba Association for Residential and Community Care Homes for Everyone ( MARCHE), the umbrella organization for 24 not-for-profit personal care homes in Manitoba; and a representative of the WRHA.

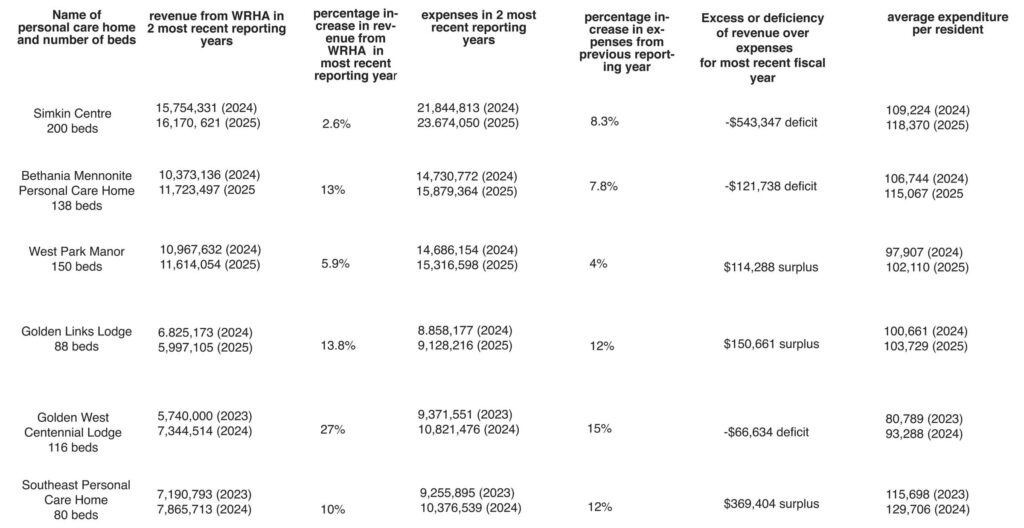

I also looked at financial statements for six different not-for-profit PCHs in Winnipeg. (Financial statements for some, but not all PCHs, are available to look at on the Province of Manitoba website. Some of those financial statements are for 2025 while others are for 2024. Still, looking at them together provides a good idea how comparable revenue and expenses are for different PCHs.)

How personal care homes are funded

In order to gain a better understanding of how personal care homes are funded it should be understood that the WRHA maintains supervision of 39 different personal care homes in Winnipeg, some of which are privately run but most of which are not-for-profit. The WRHA provides funding for all personal care homes at a rate of approximately 75% of all operational funding needs and there have been regular increases in funding over the years for certain aspects of operations (including wages, benefits, and maintenance of the homes) but, as shall be explained later, increases in funding for food have not been included in those increases.

The balance of funding for PCHs comes from residential fees (which are set by the provincial government and which are tied to income); occasional funding from the provincial government to “improve services, technology, and staffing within personal care homes,”; and funds that some PCHs are able to raise on their own through various means (such as the Simkin Centre Foundation).

But, in Longhurst’s article about personal care homes he noted that there are huge disparities in the levels of service provided among different homes.

He wrote: “Some of Winnipeg’s 37 personal-care homes provide food that is mass-produced in an off-site commercial kitchen, frozen and then reheated and served to residents.” (I should note that different sources use different figures for the number of PCHs in Winnipeg. Longhurst’s article uses the figure “37,” while the WRHA’s website says the number is “39.” My guess is that the difference is a result of three different homes operated together by the same organization under the name “Actionmarguerite.”)

How does the WRHA determine how much to fund each home?

So, if different homes provide quite different levels of service, how does the WRHA determine how much to fund each home?

For an answer, I turned to Gladys Hrabi of MARCHE, who gave me a fairly complicated explanation. According to Gladys, the “WRHA uses what’s called a global/median rate funding model. This means all PCHs—regardless of size, ownership, or actual costs—are funded at roughly the same daily rate per resident. For 2023/24, that rate (including the resident charge) was about $200+ (sorry I need to check with WRHA the actual rate) per resident day.”

But, if different residents pay different resident charges, wouldn’t that mean that if a home had a much larger number of residents who were paying the maximum residential rate (which is currently set at $37,000 per year) then that home would have much greater revenue? I wondered.

Laurie Cerqueti of the Simkin Centre provided me with an answer to that question. She wrote: “Residents at any pch pay a per diem based on income and then the government tops up to the set amount.” Thus, for the year ending March 31, 2025 residential fees brought in $5,150,657 for the Simkin Centre. That works out to approximately $27,000 per resident. I checked the financial statements for the five other PCHs in Winnipeg to which I referred earlier, and the revenue from residential fees was approximately the same per resident as what the Simkin Centre receives.

Despite large increases in funding by the WRHA for personal care homes in recent years, those increases have not gone toward food

I was still troubled by John Longhurst’s having written in his article that the “provincial government, through the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority, has not increased the amount of funding it provides for care-home residents in Manitoba since 2009.”

These days, when you perform a search on the internet, AI provides much more detailed answers to questions than what the old Google searches would.

Thus, when I asked the question: “How much funding does the WRHA provide for personal care homes in Winnipeg?” the answer was quite detailed – and specific:

“The WRHA’S total long-term care expenses for the fiscal year ended March 31, 2024 were approximately $632.05 million.” There are approximately 5,700 residents in personal care homes in Winnipeg. That figure of $632.05 million translates roughly into $111,000 per resident.

“The budget for the 2024-2025 fiscal year included a $224.3 million overall increase to the WRHA for salaries, benefits, and other expenditures, reflecting a general increase in health-care investments.” (But, note that there is no mention of an increase for food expenditures.)

But, it was as a result of an email exchange that I had with Simkin CEO Laurie Cerqueti that I understood where Longhurst’s claim that there has been no increase in funding for care-home residents since 2009 came from.

Laurie wrote: “…most, if not all of the pchs are running a deficit in the area of food due to the increases in food prices and the government/wrha not giving operational funding increases for over 15 years.” Thus, whatever increases the WRHA has been giving have been eaten up almost entirely by salary increases and some additional hiring that PCHs have been allowed to make.

Longhurst’s article focused entirely on food operations at PCHs – and how much inflation has made it so much more difficult for PCHs to continue to provide nutritious meals. He should have noted, however, that when he wrote there has been “no increase in funding for care home residents since 2009,” he was referring specifically to the area of food.

As Laurie Cerqueti noted in the same email where she observed that there has been no increase in operational funding, “approximately $300,000 of our deficit was due to food services. I do not have a specific number as far as how much of the deficit is a result of kosher food…So really this is not a kosher food issue as much is it is an inflation and funding issue.

“Our funding from the WRHA is not specific for food so I do not know how much extra they give us for kosher food. I believe years ago there was some extra funding added but it is mixed in our funding envelope and not separated out.”

So, while the WRHA has certainly increased funding for PCHs in Winnipeg, the rate of funding increases has not kept pace with the huge increases in the cost of food, especially between 2023-2024.

As Laurie Cerqueti noted, in response to an email in which I asked her how the Simkin Centre is coping with an accumulated deficit of $779,426, she wrote, in part: “The problem is that the government does not fund any of us in a way that has kept up with inflation or other cost of living increases. If this was a private industry, no one would do business with the government to lose money. I know some pchs are considering out (sic.) of the business.”

A comparison of six different personal care homes

But, when I took a careful look at the financial statements for each of the personal care homes whose financial statements I was able to download from the Province of Manitoba website, I was somewhat surprised to see the huge disparities in funding that the WRHA has allocated to different PCHs. (How I decided which PCHs to look at was simply based on whether or not I was able to download a particular PCH’s financial statement. In most cases no financial statements were available even to look at. I wonder why that is? They’re all publicly funded and all of them should be following the same requirements – wouldn’t you think?)

In addition to the Simkin Centre’s financial statement (which, as I explained, was in the Simkin Star), I was able to look at financial statements for the following personal care homes: West Park Manor, Golden West Centennial Lodge, Southeast Personal Care Home, Golden Links Lodge, and Bethania Mennonite Personal Care Home.

What I found were quite large disparities in funding levels by the WRHA among the six homes, either in 2025 (for homes that had recent financial statements available to look at) or 2024 (for homes which did not have recent financial statements to look at.)

Here is a table showing the levels of funding for six different personal care homes in Winnipeg. Although information was not available for all homes for the 2025 fiscal year, the figures here certainly show that, while the WRHA has been increasing funding for all homes – and in some cases by quite a bit, the rate of increases from one home to another has varied considerably. Further, the Simkin Centre received the lowest percentage increase from 2024 to 2025.

Comparison of funding by the WRHA for 6 different personal care homes

We did not enter into this project with any preconceived notions in mind. We simply wanted to investigate how much funding there has been from the WRHA for personal care homes in Winnipeg in recent years.

As to why some PCHs received quite large increases in funding, while others received much smaller increases – the WRHA response to my asking that question was this: “Due to the nature and complexity of the questions you are asking regarding financial information about PCHs, please collate all of your specific questions into a FIPPA and we can assess the amount of time needed to appropriately respond.”

Gladys Hrabi of MARCHE, however, offered this explanation for the relatively large disparities in funding levels among different PCHs: “Because funding is based on the median, not actual costs, each PCH must manage within the same per diem rate even though their realities differ. Factors like building age, staffing structure, kitchen setup, and resident complexity all influence spending patterns.

“The difference you found (in spending between two particular homes that I cited in an email to Gladys) likely reflects these operational differences. Homes that prepare food on-site, accommodate specialized diets (cultural i.e. kosher), or prioritize enhanced dining experiences (more than 2 choices) naturally incur higher total costs. Others may use centralized food services or have less flexibility because of budget constraints.

“The current model doesn’t adjust for inflation, collective agreements, or true cost increases. This means many homes, especially MARCHE members face operating deficits and have to make tough choices about where to contain costs, often affecting areas like food, recreation, or maintenance. The large differences you see in food spending aren’t about efficiency —–they’re a sign that the current funding model doesn’t reflect the true costs of care.”

But some of the disparities in funding of different personal care homes really jump off the page. I noted, for instance, that of the six PCHs whose financial statements I examined, the levels of funding from WRHA for the 2024 fiscal year fell between a range of $63,341 per resident (at Golden Links Lodge) to $78,771 at the Simkin Centre – but there was one particular outlier: Southeast Personal Care Home, which received funding from the WRHA in 2024 at the rate of $98,321 per resident. Not only did Southeast Personal Care Home receive a great deal more funding per resident than the other five PCHs I looked at, it had a hefty surplus to boot.

I asked a spokesperson from the WRHA to explain how one PCH could have received so much more funding per capita than other PCHs, but have not received a response.

This brings me then to the issue of the Simkin Centre and the quite large deficit situation it’s in. Since readers might have a greater interest in the situation as it exists at the Simkin Centre as opposed to other personal care homes and, as the Simkin Centre has reported quite large deficits for both 2024 and 2025, as I noted previously, I asked Laurie Cerqueti how Simkin will be dealing with its accumulated deficit (which now stands at $779,426) going forward?

Now, as many readers may also know, I’ve been harping on the extra high costs incurred by Simkin as a result of its having to remain a kosher facility. It’s not my intention to open old wounds, but I was somewhat astonished to see how much larger the Simkin Centre’s deficit is than any other PCH for which I could find financial information.

From time to time I’ve asked Laurie how many of Simkin’s 200 residents are Jewish?

On November 10, she responded that “55% of residents” at Simkin are Jewish. That figure is consistent with past numbers that Laurie has cited over the years.

And, while Laurie claims that she does not know exactly how much more the Simkin Centre pays for kosher food, the increases in costs for kosher beef and chicken have outstripped the increases in costs for nonkosher beef and chicken. Here is what we found when we looked at the differences in prices between kosher and nonkosher beef and chicken: “Based on recent data and long-standing market factors, kosher beef and chicken prices have generally gone up more than non-kosher (conventional beef and chicken). Both types of meat have experienced significant inflation due to broader economic pressures and supply chain issues, but the kosher market has additional, unique cost drivers that amplify these increases.”

In the final analysis, while the WRHA has been providing fairly large increases in funding to personal care homes in Winnipeg, those increases have been eaten up by higher payroll costs and the costs of simply maintaining what is very often aging infrastructure. If the WRHA does not provide any increases for food costs, personal care homes will continue to be squeezed financially. They can either reduce the quality of food they offer residents or find other areas, such as programming, where they might be able to make cuts.

But, the situation at the Simkin Centre, which is running a much larger accumulated deficit than any other personal care home for which we could find financial information, places it in a very difficult position. How the Simkin Centre will deal with that deficit is a huge challenge. The only body that can provide help in a major way, not only for the Simkin Centre, but for all personal care homes within Manitoba, is the provincial government. Perhaps if you’re reading this you might want to contact your local MLA and voice your concerns about the lack of increased funding for food at PCHs.

Local News

2026 Winnipeg Limmud to offer a smorgasbord of diverse speakers

By MYRON LOVE There are many facets to the study of Judaism and the Jewish people. The focus may be religious or cultural, historical or Israel-oriented – and Winnipeg’s annual Limmud Festival for Jewish Learning has always striven to cover as many angles as possible.

This year’s Limmud program (now in its 16th year) – scheduled for Sunday, March 15 – is following in that path with a diverse group of presenters.

Limmud’s current co-ordinator, Raya Margulets, reports that all of our community’s rabbis – including Rabbi Yossi Benarroch (who lives most of the year in Israel) – will be among the presenters. Topics to be covered by local experts encompass midrash, Jewish identity, antisemitism, conversion, biblical archaeology, textiles, parenting, art, and more.

But it wouldn’t be Limmud without interesting input from out of town personalities.

Perhaps the most prominent of the guest speakers who are confirmed is Yaron Deckel, an Israeli journalist and broadcaster who is currently the Jewish Agency’s Regional Director for Canada. According to a biography provided by Margulets, Deckel is a highly respected Israeli journalist widely known for his insight into Israeli politics, media, and society. Between 2002 and 2007, Yaron served as Washington Bureau Chief for Israeli Public Television. In that role, he covered U.S.–Israel relations and American politics, also interviewed three U.S. presidents: George W. Bush, Bill Clinton, and Jimmy Carter. As well, Deckel produced two acclaimed documentaries: “The Israelis” (about the lives of Israelis in North America), and “Jewish Identity in North America.”

From 2012 to 2017, he served as Editor-in-Chief and CEO of Galei Tzahal (IDF Radio), Israel’s leading national public radio station. He also hosted a prime-time weekly political show.

As a senior political correspondent and commentator for Israeli TV and radio, Yaron has covered the past 14 Israeli election campaigns and maintained close relationships with top political and military leaders in Israel. He conducted the last interview with Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin—just 10 minutes before his assassination.

Decker is slated to do two presentations. In the morning, he will be speaking about the crossroads that Israel finds in the Middle East currently and what the challenges and possibilities may be.

In the afternoon, his subject will be “Israel after October 7 and the Iran War “ and what may lie ahead.

Also coming in from Toronto are Atarah Derrick, Achiya Klein, and Yahav Barnea.

Barnea is an Israeli-Canadian educator and community builder based in Toronto, with over a decade of experience working in Jewish and Israeli education, engagement, and community development.

Originally from Kibbutz Shomrat in Israel’s Western Galilee, Barnea’s outlook on life has been shaped by kibbutz values and her involvement in the Hashomer Hatza’ir youth movement.

She currently serves as the North America Regional Program Manager for the World Zionist Organization’s Department of Irgoon and Israelis Abroad, where she leads initiatives that strengthen connection, leadership, and communal life among Israelis living outside of Israel..

Barnea holds a Master of Education in Adult Education and Community Development, with a focus on intentional communities, as well as a Bachelor of Education specializing in Democratic Education, meaningful, values-based communities.

Her presentation will be titeld “A Kibbutz in the City – Intentional Communities and Immigration.”

Atarah Derrick is the executive director of the Israel Guide Dog Center for the Blind, an organization that is dedicated to improving the quality of life of visually impaired Israelis. The charity, the only internationally accredited guide dog program in Israel, was founded in 1991, and today serves Israel’s 24,000 blind and visually impaired citizens.

Achiya Klein is one of the guide dog centre’s beneficiaries. The Israeli veteran was an officer in the IDF combat engineering corps’ elite ‘Yahalom’ unit. In 2013, while on a sensitive mission to disable a tunnel in Gaza, an improvised explosive device was detonated, severely injuring Achiya and robbing him of his vision.

He has been a guide dog client since 2015.

Klein has not allowed his disability to limit his abilities. He competed for the Israeli national team at the Paralympic rowing championship in the Tokyo 2021 Olympics.

He also earned a Masters Degree in the Lauder School of Government, Diplomacy and Strategy in Counter Terrorism and Homeland Security,at IDC Herzliya.

Klein is married and a father to two boys.

Coming back for a second successive year is Dan Ronis from Saskatoon. A plant breeder and geneticist, Ronis has taken a quite different approach to studying Torah. He has sought out the help of a medium to discern the back stories of Biblical figures.

For readers who may be unsure of who or what a medium is, think Theresa Caputo of television fame. Mediums claim to be able to converse with those who have passed on through a spirit guide. While many may be skeptical, there are also many believers.

Last year Ronis focused on women who played a prominent role in the Torah. This year, he will be discussing the “untold story” of Adam and Eve.

Readers who may be interested in attending Limmud 2026 can go online at limmudwinnipeg.org to register.

Local News

Second annual “Taste of Limmud” a rousing success

By MYRON LOVE “A Taste of Limmud” returned for a second go-round on Thursday, February 19, and I have to commend both Raya Margulets, Winnipeg Limmud’s co-ordinator, as well as the Shaarey Zedek Synagogue’s catering department, for an outstanding culinary experience delivered with flawless efficiency.

“Tonight’s Taste of Limmud showcases our diversity as a community and our unity as we come together to break bread,” observed Rena Secter Elbaze, Shaarey Zedek’s executive director, just prior to leading the guests in hamotzi.

The evening featured a sampling of Jewish staple dishes representing Jewish life in six different regions where Jews had settled over the centuries. The choice of dishes also reflected how diversified our Jewish community has become over the past 25 years.

In her opening remarks, Margulets welcomed her 130 guests. “After last year’s success,” she said many of you asked us to bring it back, and we’re delighted to do so, so welcome again. Today’s celebration is all about sharing stories, connections, and flavours, and it is brought to you in partnership with Congregation Shaarey Zedek and with the support of the Jewish Foundation of Manitoba.

“We would like to take a moment and express our heartfelt gratitude to Congregation Shaarey Zedek for their amazing partnership, to Joel, the Head Chef at Shaarey Zedek, and his fantastic staff for their contributions, and to all the volunteers who made tonight possible,” Margulets said.

“Thank you all for joining us tonight. Savour the flavours, the stories, and the connections as we celebrate the richness of Jewish cuisine and community together.

“Whether you’re returning or attending for the first time,” she continued, “we’re excited to stir up a wonderful evening with old and new friends. Some of you may have realized it already, but the name Taste of Limmud has a double meaning. While, yes, this event is all about taste and sampling Jewish flavours from around the world, it is also a tiny glimpse, in other words, a taste, into our established annual Limmud Festival.”

Limmud, she explained – the Hebrew word for “learning”, is a volunteer-run organization that celebrates Jewish learning, thought, and culture. It’s a conference where participants have a choice of dozens of sessions led by rabbis, scholars, artists, authors, and community members. At Limmud, everyone can be a teacher and a student, in other words, more fitting with tonight’s theme, everyone has something to add to the recipe.

Margulets then introduced the “talented cooks from our very own community who prepared the dishes”: Mazi Frank, who presented a “delicious” Mussakah, a Turkish classic; Adriana Vegh-Levy and Karina Izbizky who brought a “tasty” Pletzalej, a type of bread that the forebears of today’s Argenitnian Jewish community brought with them from Poland; Karen Ackerman, with a special Hard Honey Cake; Naama Samphir, who presented a tasty Yemenite Hawaij soup (and that’s right – Hawaij – not Hawaii; Hawaij is Iraqi); Kseniya Revzin ,sharing a rich Kubbete, a savory pie from the Crimean Karaites; and Ruth Harari, (who wasn’t able to join her sister cooks) who had prepared Mujadara, a flavourful lentil-and-rice dish from Aleppo, Syria.

“We would like to take a moment and express our heartfelt gratitude to Congregation Shaarey Zedek for their amazing partnership, to Joel, the Head Chef at Shaarey Zedek, and his fantastic staff for their contributions, and to all the volunteers who made tonight possible,” Raya Margulets concluded.

“Thank you all for joining us tonight. Savour the flavours, the stories, and the connections as we celebrate the richness of Jewish cuisine and community together.”

The six samplings were dished out – one at a time – in either small paper plates or cups with the paper removed after each tasting.

The first recipe to be presented was pletzalej onion bread. As was the pattern for each tasting, the first food presented was preceded by a brief overview of the history of Argentina’s Jewish community and its connection with its local contributor, followed by a plezelaj bun with a piece of meat inside .

Next up was a taste of Hawaij soup, a Shabbat and Yom Tov staple of Yemen’s former centuries-old Jewish community, most of whom are now in Israel. The soup included piecesof chicken, potatoes, onions, carrots, tomato and several spices. Hawaij is a spice mixture consisting of cumin, black pepper, turmeric and cardamom.

Mussakah comes from Turkey – also a homeland for Jews for hundreds of years. It is a mixture of layered eggplant, beef, savoury tomato sauce and spices and is typically served with rice or a piece of bread.

Mujadara is a product of the ancient Syrian city of Aleppo, one of the world’s oldest cities and formerly home for thousands of years to a once thriving Jewish community. The recipe calls for lentils, basmati rice, onions and spices.

Kubbete is a puff pastry originally from Crimea, where the local Jewish community picked it up from the surrounding Tatar population. The pastry is filled with beef (as was the case that evening) or lamb, onions, potatoes and peppercorn, with paprika added for taste.

The last item on the menu was hard honey cake. “This was my baba’s recipem which she brought with her from Ukraine in the 1920s,” noted Karen Ackerman. “Jews like my baba (Chava Portnoy) have lived in Ukraine for over 1,000 years and they used the local buckwheat honey in their honey cake.

“I am honoured to be able to share this recipe with you,” she said.

All the presenters spoke of how the recipes that had been passed down through the generations connected them with home and family and memories of their babas.

I once had a cousin who, after enjoying a hearty meal, would say: “Good Sample. When do we eat? Well, after the sampling, it really was time for a late supper – the main course – and it was a perfect way to end the evening feasting on pita filled with veggies, falafel balls and humus and French fries with a choice of coffee cake or chocolate cake for dessert.

I ‘m really looking forward to next year’s “Taste of Limmud”.

Local News

New kosher caterer providing traditional Israeli foods for Winnipeg palates

By MYRON LOVE The Israeli community in Winnipeg continues to grow and enrich our community. Among the most recent arrivals are Maxim and Olga Markov – along with their children, who settled here less than two years ago. What the Markovs are contributing to our community is a new kosher catering operation – Bravo Good Food – that specializes in traditional Israeli fare.

The senior Markovs are both originally from Ukraine. They came with their families in the early 1990s when they were young teenagers. For the last several years before moving to Winnipeg, they lived in Afula in north central Israel.

After their arrival in Winnipeg, Olga worked for a time in the Chabad kitchen; Yural still works in the Chabad daycare – while Maxim took a job with an HVAC company.

Maxim’s passion however, and his life’s work has been in food preparation. He points out that he worked in the business for 17 years in Israel. In the early part of his career, he was head chef in a dairy restaurant. He was also a cook in wedding halls preparing food for as many as 1,000 guests.

In more recent years, he worked in a private hospital kitchen where, he notes, he gained experience with dietary menus and healthy food options.

“What we do at Bravo,” he says, “is provide our clientele with the authentic taste of the Middle East. We cook traditional dishes, using only fresh ingredients, with our own original recipes.”

Operating out of the Adas Yeshurun-Herzlia kitchen, Bravo’s menu (which readers can view on its website – bravogoodfood.com) features such well known Israeli items as falafel balls and humus, mini shislek (with chicken) on skewers, beef kebabs on cinnamon sticks, and friend eggplant with tahini.

But there is much more to choose from.

Start with salads.

You can choose from coleslaw, purple cabbage salad, beet salad with pears, celery and parsley, mushroom salad, and green herb salad.

Main course options include beef meatballs and tomato sauce with a trio of fish dishes – salmon, Moroccan fish, and custom fried fish. Also available are a broccoli casserole, pasta, and spaghetti.

Bravo also offers a corporate menu featuring a choice of continental or executive breakfast, full breakfast buffet or a buffet of mini sandwiches – and an events menu.

Maxim adds that Bravo offers vegetarian, vegan and gluten free options.

Olga notes that individual dishes or baking can be ready for the next day. “If it’s a small event like a family dinner, we need at least three days in advance, provided the date is available,” she says. “If it’s a large event – then we need at least a week in advance notice.”

“We are not just providing food,” Maxim says. “We are creating an atmosphere. Our catering makes your event unforgettable through taste, freshness and hospitality.”