Features

Daniel Raiskin, music director of the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra, discusses his life – from his boyhood in Soviet Russia to his coming to Winnipeg and his admiration for the Jewish community here

By BERNIE BELLAN Daniel Raiskin has been the music director of the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra since 2018. This paper has been remiss not to have interviewed Raiskin until now, although to be fair to ourselves, he is an extremely busy fellow,

so finding a time when he could sit down and talk about his career, what life was like growing up in a Jewish family in Soviet Russia, and how he feels about spending a good part of his time in Winnipeg, was not easily arranged.

But then Covid-19 suddenly took over everyone’s lives – no matter who they are or where they live and, without much planning required, we were able to arrange to speak with Raiskin from his Amsterdam home.

At the outset of our conversation, which was conducted via WhatsAapp on Friday, April 3, Raiskin explained he’s “lived in Amsterdam for 30 years.” While he travels the world serving as guest conductor for many different orchestras, he “shares his time between Winnipeg and Amsterdam. My home is both in Amsterdam and Winnipeg,” he said.

I asked him, since he’s lived in The Netherlands for so many years whether he holds Dutch citizenship? Raiskin answered that he’s been a Dutch citizen for 26 years, although he still “has a Russian passport, too.”

At the present time Raiskin is also resigned, like the rest of us, to remaining in his Amsterdam home with his wife and two children (a son, 21, and a daughter, 16) for the foreseeable future..

“I was actually caught here between two projects – both of which were in Winnipeg,” Raiskin explained. “I was supposed to return to Winnipeg to spend 10 days there, but then things began to get really cloudy and we decided it doesn’t make any sense for me to fly into Winnipeg and get stuck there without my family, so I decided to stay here.”

We discussed how The Netherlands had taken a relatively hands-off approach to the Coronavirus to begin with, but as the danger has become more apparent, the liberal attitudes that most Dutch have in being uncomfortable with seeing their liberties restricted have begun to dissipate.

“People here are used to going to parks and to the seaside, but I’m afraid that on Monday (April 6) the lockdown is going to be announced,” Raiskin observed (on April 3).

Before we began to talk about Raiskin’s musical career, I said to him that I wanted “to take him back to his childhood in St. Petersburg.” I remarked to him that when I was a student in Israel (a very long time ago – 1974-75 to be exact). I became friends with a girl from St. Petersburg, who bragged to me that people from St. Petersburg were so much more sophisticated than Israelis, also that St. Petersburg had “the best ice cream in the world.”

I asked Raiskin whether the part about the ice cream was true.

“Yes, that ‘s very true,” he responded – “at least judging from my kids’ reaction any time we go to St. Petersburg, they say ‘this is really the best tasting ice cream.’ “

I wondered whether Raiskin was a musical prodigy as a child.

“I was not a prodigy at all,” he said. “I took up the violin when I was six – and I didn’t ‘take it up’. I was given it. It’s an old joke that with the wave of Russian Jewish immigration to Israel every second Russian landing in Israel at Ben Gurion Airport had a violin in his or her hands. Those that did not were piano players.”

“I was born into a Jewish family where music played a very important role,” Raiskin explained.

“My father is one of the foremost Russian musicologists (who is also a now retired physicist, Raiskin noted). One of the first sounds I heard when I was born was my brother (who tragically died at a the age of 34) practising his cello. By the time I was six – I like to joke my mother was so tired of carrying my brother’s cello around, she opted for something smaller for me: a violin.”

By the way, both Rasikin’s parents are alive and still living in St. Petersburg, he told me. His father’s first love was always music, Raiskin noted, but as part of the generation that grew up in the Soviet Union following World War II, it was unrealistic for anyone to make a career of music, he explained.

“He was teaching physics at a university in St. Petersburg when he was 35, but he graduated from a music conservatory when he was 40. That goes to show how important music was to him,” Raiskin observed.

“My mother stopped working a year ago (when she was 82),” Raiskin said. “She was a mathematician and a software programmer.”

I asked Raiskin whether his “parents ever endured any discrimination because they were Jewish that you can speak of? ” I added that “I didn’t want to seem naive by asking the question (since anyone who was following the fight of “refuseniks” in Russia attempting to leave Russia at the time that Raiskin was growing up would have known that anti-Semitism was rampant in that country.

” We lived in a country with a great rate of anti-Semitism,’ Raiskin answered. “My parents and my brother and me and friends all around us were all subject to state-sponsored anti-Semitism. At some point my family had also made the decision to leave (Russia), but it was too late. The Afghanistan war had broken out and everything was hermetically sealed. We got stuck.”

At that point I said to Raiskin that I wanted to talk about what it was like growing up as a young Jewish boy in Russia at that time – and how much love of music was inculcated into his and his peers’ lives.

“It was like – any given picture of Chagall has a violin in it,” Raiskin observed. “It’s part of the Jewish heritage and DNA; this whole ‘3,000 years of endurance’. Music was one of the things that kept us from getting alienated.”

At the same time though, Raiskin said that “music was not something that I particularly wanted to do. I wanted to play football and ice hockey with my mates outside. As a kid you don’t want to spend hours practising and doing scales for hours, looking out the window of your seventh-floor apartment while other kids are playing outside. I wanted to be more like them.”

“It’s very often a mistake to think that it’s the child who makes the decision at age six or seven to become a musician. Some kids are so incredibly gifted they show a unique talent at such a young age, there’s nothing else they want to do. I definitely don’t want to give the impression that I was one of those kids. I was pretty much normal and not very well behaved; I was pretty naughty.

“It was only later that I developed a real taste for music – and worked hard to become something.”

To that point we hadn’t discussed Raiskin’s particular musical interests. I noted that I had read in various articles and interviews that his favourite composer was Gustav Mahler (who was also Jewish, by the way). I wondered when Raiskin first became interested in Mahler’s music?

“You know, in fact, Mahler was not a composer whose music was very often played in my years in the Soviet Union,” Raiskin explained. “The performances of Mahler were always a great event,” but it was only one or two of his symphonies that were ever played, he noted.

“It was only with the collapse of the Soviet Union and the first Western orchestras that started to come on European tours that we really started to hear Mahler played. I’ll never forget the first time I heard Mahler’s Seventh Symphony played by the Pittsburgh Symphony…I think this was when it really hit me hard. This is the moment that I said to myself: ‘I’m going to conduct this once’…and I did, on many occasions…I try to conduct his music as often as I can.”

We skipped ahead to Raiskin’s first time coming to Winnipeg which, he said, was in 2015, as guest conductor of the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra. There were two more appearances as guest conductor of the WSO in 2017 before Raiskin was appointed as music director in 2018.

“It was a lengthy process,” he said, “but I am, in fact, already looking back on five years of being associated with Winnipeg. It’s not like it started in 2018.”

Raiskin also observed that “no matter how successful a relationship a music director has with an orchestra – it’s never a relationship for life. It’s just the nature of the profession. It’s a marriage for a time…It’s not the conductors who play the music; it’s the orchestras. It’s about 67 musicians who play. It’s very important – the mandate we get from the musicians …and at a certain point it’s time for the conductor to go.”

However, Raiskin wanted to make clear that this is not something he is thinking about now. With his second season cut short due to the COVID-19 pandemic, he said that, |“more than ever our relationship and interdependency is being tested and I am confident we’ll get out if the crisis, whenever this might be, stronger than ever.“

Raiskin explained that, while he is contractually obligated to conduct the WSO for 12 weeks during the year, it is hugely important for any conductor to get out on the road as much as possible. He used the following analogy to illustrate his point: “A hockey player cannot perform at the highest level of his ability if he just plays home games. It’s also important how you perform outside.”

I noted at the outset of this article that, although Daniel Raiskin has been music director of the WSO for two years now, we still hadn’t interviewed him which, given that we’re a Jewish newspaper and he’s Jewish, is something that we should have done much earlier. But, since he’s now had time to get to know Winnipeg – and its Jewish community, much better, I asked him what his impression of our community was?

“I’m sure you’ve met Gail Asper,” I said (tongue in cheek; how could the music director of the WSO not have met one of the foremost supporters of the WSO – and arts in general in this city?)

“Yes, of course,” came Raiskin’s reply, “and many other people, like Laurel Malkin, and Michel Kay and Glenna Kay. You know, Winnipeg became a place where being Jewish for me suddenly started to matter in a very personal and positive way. Growing up in the Soviet Union was definitely not. I was once expelled from a music conservatory for visiting a synagogue – for the first time, just out of curiosity.

“And when you’re in a very cosmopolitan city like Amsterdam, with a very tragic history of Dutch Jews – one needs to acknowledge that there were 150,000 Dutch Jews before the Second World War, and only 15,000 survived – so, for me, connecting to the Jewish community here…like the first Rosh Hashanah dinner I ever attended was…in Winnipeg! Because some friends just took me and my wife and said: ‘Come’. I really feel that it matters in a very positive way that I’m Jewish and I can connect to many people in Winnipeg and many in our audiences are Jewish.”

“I feel more Jewish than ever since coming to Winnipeg,” Raiskin suggested. “Jewish music is so important to me. One of the first things I recorded as a musician – as an instrumentalist, was a complete edition of music for viola and piano by Ernst Bloch, the foremost Jewish composer.”

At the end of our interview we discussed the devastating effect that the current crisis is having on people’s lives – in so many ways. Raiskin said that he was still fully involved in planning for the coming season of the WSO – and for the season after that as well.

In terms of assessing people’s hunger for music, he had this to say: “I think there will be a sense of growing hunger…our souls and our spirits are being so hollowed, there will be a growing need to fill in this gap – and this is where we can step in.”

Raiskin closed our interview with this observation: “I feel: today, more than ever, people feel how important arts and culture are to them. We suddenly realize that we use art to communicate with each other!“

Features

Omri Casspi’s Career: from Israel to the NBA

Whenever people discuss modern basketball, as it relates to Israel, Omri Casspi is one name that is generally mentioned, not because he amassed the highest NBA numbers, nor because he was one individual that dominated the game for a long period. It is because Omri was one individual that illustrated how a basketball player from a small town in Israel could make it to the most competitive basketball league in the world.

Online gaming websites are of interest to several industries. Some may investigate other forms of electronic entertainment beyond traditional sports. The website http://billionairespins.com/ It works as an online casino, where users are required to register, pick games, and play through the website-based system. It’s entirely an online system, which implies that players use internet-based devices such as computers and mobile devices to play, rather than attending the location. Accordingly, the use of the casino is entirely web-based.

Casspi’s story starts well outside the hallowed courts of the NBA. Casspi was born in Yavne, Israel, on June 22, 1988. Like so many tall kids, he gravitated towards basketball when he was young. Coaches first noticed size, then coordination and confidence. He did not play for fun. He competed. He trained. He listened.

As an adolescent, he enrolled in organized youth programs that required discipline. Practices concentrated on fundamentals: footwork, shooting form, defensive position. He learned to play in a team concept, instead of seeking attention. That mind-set stayed with him throughout his career.

His next team was signed when he was still young, and this team, Maccabi Tel Aviv, played at the highest level. The team played hard in Europe as well. Not only did this team compete hard, but they played in an environment where making a mistake had serious repercussions.

He concentrated on particular parts of his game:

- Improving Three-Point Accuracy

- Building strength to handle contact

- Understanding spacing in half court sets.

- Moving Without the Ball to Create Options

However, he did not explode onto the scene right away. His minutes were accumulated over time. Come the 2008-2009 season, he was averaging double figures in Israel and proving he could extend the floor. Scouts from the United States were taking note. With his height and shooting ability to spread the floor, the NBA was slowly going to take a different turn.

Draft Night and Adjustment to the NBA

Casspi decided to enter the NBA Draft in 2009. He was picked by the Sacramento Kings on the 23rd overall spot. With this selection, Casspi became the first Israeli-born player to be selected for the league. This was a historic selection, but Casspi knew symbolic value would not get him playing minutes.

The NBA is an unforgiving environment in that players must quickly adjust. The schedule is grueling. Travel involves crossing time zones. Teams take advantage of those who wait to react. Casspi began the training camp with the goal to prove himself through performance.

He earned rotation minutes as a rookie. Coaches were impressed by his willingness to shoot when he was open and his efforts on transition. For the 2009-2010 season, he averaged 10.3 points and 4.5 rebounds per game. He scored 30 points against the Golden State Warriors, and he won the Western Conference Rookie of the Month award in December 2009.

Those numbers are important but not in any way which defines him totally. He was a player the team could count on because he moved without the ball and therefore would not demand the ball. He defends within the structure. He also played hard even though the touches were limited.

A Career Marked by Movement

Professional basketball is a sport that rarely guarantees long-term stability for role players. Sacramento traded Casspi to the Cleveland Cavaliers in 2011. Casspi adjusted well in the new system and took on a reduced role. This is a test of the player’s mindset.

He eventually signed with the Houston Rockets, with whom he played primarily as a perimeter shooter. He was expected to make quick decisions. He played with a number of teams over the years wearing different uniforms:

- Sacramento Kings

- Cleveland Cavaliers

- Houston Rockets

- New Orleans Pelicans

- Minnesota Timberwolves

- Golden State Warriors

- Memphis Grizzlies

Each transition needed a dose of humility. He’d walk into new locker rooms where he’d need to rebuild trust. Some seasons, the playing time was consistent; others, his role was limited. Trades were out of his hands, but preparation wasn’t.

His career averages reflect that steady presence:

Casspi was primarily used as a small forward. In some formations, he was used as a power forward. His game was not based on isolation basketball; rather, he relied on his awareness.

He was good at scoring those types of shots, or catch-and-shoots. His opponents had to respect his shooting. When they did close out on him, he attacked the rim with long strides. He never lied to himself about his commitment to a scoring attempt.

His strengths stood out clearly:

- Shot selection outside

- Smart off-ball movement

- Team-oriented defense

- Strong Effort in Transition

He approached defense with discipline. He played the position and avoided taking unnecessary risks. Coaches appreciated that.

Experience with a Contender

In 2017, Casspi signed with the Golden State Warriors. The team competed with championship expectations and executed at high speed. Casspi took a limited but defined role. He focused on the need for efficiency.

He averaged 5.7 points per game in restricted minutes. An ankle injury interrupted his rhythm, and the Warriors waived him late in the regular season. Even then, he experienced preparation day-to-day at the very highest level of competition. Practices called for concentration and precise execution.

National Team Engagement

Through all NBA years, Casspi never abandoned Israel’s national team. International competition often placed more responsibility on his shoulders. He carried larger scoring loads and acted as a leader for younger teammates.

His presence in the NBA shifted perception inside Israel: Young players saw tangible proof that advancement to the league did not remain a distant idea. Scouts evaluated Israeli talent with greater interest.

Features

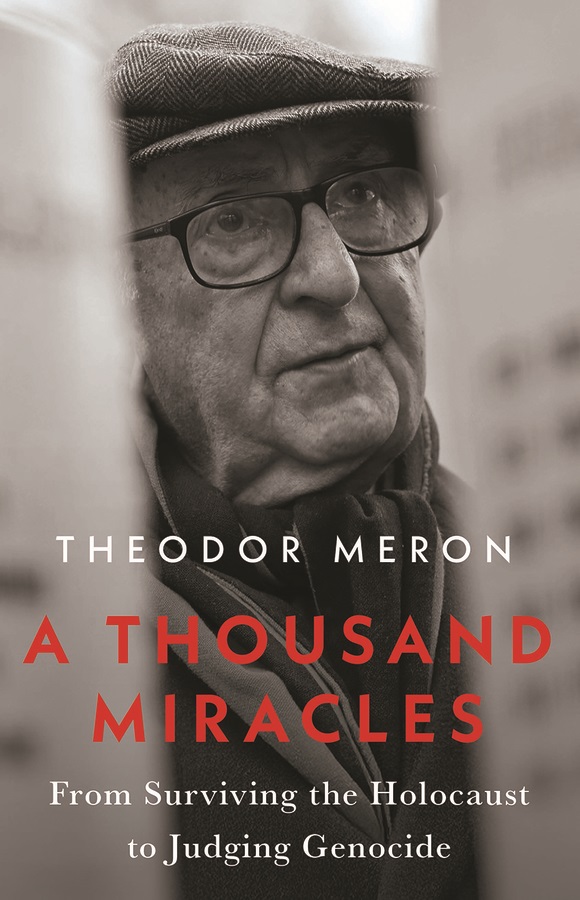

A Thousand Miracles: From Surviving the Holocaust to Judging Genocide

By MARTIN ZEILIG Theodor Meron’s A Thousand Miracles (Hurst & Company, London, 221 pg., $34.00 USD) is an uncommon memoir—one that links the terror of the Holocaust with the painstaking creation of the legal institutions meant to prevent future atrocities.

It is both intimate and historically expansive, tracing Meron’s path from a child in hiding to one of the most influential jurists in modern international law.

The early chapters recount Meron’s survival in Nazi occupied Poland through a series of improbable escapes and acts of kindness—the “miracles” of the title. Rendered with restraint rather than dramatization, these memories form the ethical foundation of his later work.

That moral clarity is evident decades later when, on the seventy-fifth anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, he addressed the UN General Assembly and reminded the world that “the German killing machine did not target Jews only but also the Roma, Poles, Russians and others,” while honoring “the Just—who risked their lives to save Jews.” It is a moment that encapsulates his lifelong insistence on historical accuracy and universal human dignity.

What sets this memoir apart is its second half, which follows Meron’s transformation into a central architect of international humanitarian law. Before entering academia full time, he served in Israel’s diplomatic corps, including a formative posting as ambassador to Canada in the early 1970s. Ottawa under Pierre Trudeau was, as he recalls, “an exciting, vibrant place,” and Meron’s responsibilities extended far beyond traditional diplomacy: representing Israel to the Canadian Jewish community, travelling frequently to Toronto, Montreal, and Vancouver, and even helping to promote sales of Israeli government bonds. His affection for Canada’s cultural life—Montreal’s theatre, Vancouver’s “stunning vistas”—is matched by his candor about the political pressures of the job.

One episode proved decisive.

He was instructed to urge Canadian Jewish leaders to pressure their government to move the embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem—a request he found ethically questionable. His refusal provoked an attempt to recall him, a move that reached the Israeli cabinet. Only the intervention of Finance Minister Pinhas Sapir, who valued Meron’s work, prevented his dismissal. The incident, he writes, left “a fairly bitter taste” and intensified his desire for an academic life—an early sign of the independence that would define his legal career.

That independence is nowhere more evident than in one of the most contentious issues he faced as legal adviser to the Israeli Foreign Ministry: the legal status of Israeli settlements in the occupied West Bank. Meron recounts being asked to provide an opinion on the legality of establishing civilian settlements in territory captured in 1967.

His conclusion was unequivocal: such settlements violated the Fourth Geneva Convention as well as the private property rights of the Arab inhabitants. The government chose a different path, and a wave of settlements followed, complicating prospects for a political solution. Years later, traveling through the West Bank, he was deeply troubled by the sight of Jewish settlers obstructing Palestinian farmers, making it difficult—and at times dangerous—for them to reach their olive groves, even uprooting trees that take decades to grow.

“How could they impose on Arab inhabitants a myriad of restrictions that did not apply to the Jewish settlers?” he asks. “How could Jews, who had suffered extreme persecution through the centuries, show so little compassion for the Arab inhabitants?”

Although he knew his opinion was not the one the government wanted, he believed firmly that legal advisers must “call the law as they see it.” To the government’s credit, he notes, there were no repercussions for his unpopular stance. The opinion, grounded in human rights and humanitarian law, has since become one of his most cited and influential.

Meron’s academic trajectory, detailed in the memoir, is remarkable in its breadth.

His year at the Max Planck Institute in Heidelberg (1984–85) produced Human Rights Law–Making in the United Nations, which won the American Society of International Law’s annual best book prize. He held visiting positions at Harvard Law School, Berkeley, and twice at All Souls College, Oxford.

He was elected to the Council on Foreign Relations in 1992 and, in 1997, to the prestigious Institute of International Law in Strasbourg. In 2003 he delivered the general course at the Hague Academy of International Law, and the following year received the International Bar Association’s Rule of Law Award. These milestones are presented not as selfpromotion but as steps in a lifelong effort to strengthen the legal protections he once lacked as a child.

His reflections on building the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY)—balancing legal rigor with political constraints, and confronting crimes that echoed his own childhood trauma—are among the book’s most compelling passages. He writes with unusual candor about the emotional weight of judging atrocities that, in many ways, mirrored the violence he narrowly escaped as a boy.

Meron’s influence, however, extends far beyond the Balkans.

The memoir revisits his confidential 1967 legal opinion for the U.S. State Department, in which he concluded that Israeli settlements in the territories occupied after the Six Day War violated international humanitarian law—a view consistent with the opinion he delivered to the Israeli government itself. His distress at witnessing settlers obstruct Palestinian farmers and uproot olive trees underscores a recurring theme: the obligation of legal advisers to uphold the law even when politically inconvenient.

The book also highlights his role in shaping the International Criminal Court (ICC). Meron recalls being “happy and excited to be able to help in the construction of the first ever permanent international criminal court” at the 1998 Rome Conference.

His discussion of the ICC’s current work is characteristically balanced: while “most crimes appear to have been committed by the Russians” in Ukraine, he notes that “some crimes may have been committed by the Ukrainians as well,” underscoring the prosecutor’s obligation to investigate all sides.

He also points to the ICC’s arrest warrants for President Putin, for Hamas leaders for crimes committed on October 7, 2023, and for two Israeli cabinet members for crimes in Gaza—examples of the Court’s mandate to pursue accountability impartially, even when doing so is politically fraught.

Throughout, Meron acknowledges the limitations of international justice—the slow pace, the uneven enforcement, the geopolitical pressures—but insists on its necessity. For him, law is not a cureall but a fragile bulwark against the collapse of humanity he witnessed as a child. His reflections remind the reader that international law, however imperfect, remains one of the few tools available to restrain the powerful and protect the vulnerable.

The memoir is also a quiet love story.

Meron’s devotion to his late wife, Monique Jonquet Meron, adds warmth and grounding to a life spent confronting humanity’s darkest chapters. Their partnership provides a counterpoint to the grim subject matter of his professional work and reveals the personal resilience that sustained him.

Written with precision and modesty, A Thousand Miracles avoids selfaggrandizement even as it recounts a career that helped shape the modern architecture of international justice.

The result is a powerful testament to resilience and moral purpose—a reminder that survivors of atrocity can become builders of a more just world.

Martin Zeilig’s Interview with Judge Theodore Meron: Memory, Justice, and the Life He Never Expected

In an email interview with jewishpostandnews.ca , the 95 year-old jurist reflects on survival, legacy, and the moral demands of international law.

Few figures in modern international law have lived a life as improbable—or as influential—as Judge Theodore Meron. Holocaust survivor, scholar, adviser to governments, president of multiple UN war crimes tribunals, Oxford professor, and now a published poet at 95, Meron has spent decades shaping the global pursuit of justice. His new memoir, A Thousand Miracles, captures that extraordinary journey.

He discussed the emotional challenges of writing the book, the principles that guided his career, and the woman whose influence shaped his life.

Meron says the memoir began as an act of love and remembrance, a way to honor the person who anchored his life.

“The critical drive to write A Thousand Miracles was my desire to create a legacy for my wife, Monique, who played such a great role in my life.”

Her presence, he explains, was not only personal but moral—“a compass for living an honorable life… having law and justice as my lodestar, and never cutting corners.”

Reflecting on the past meant confronting memories he had long held at a distance. Writing forced him back into the emotional terrain of childhood loss and wartime survival.

“I found it difficult to write and to think of the loss of my Mother and Brother… my loss of childhood and school… my narrow escapes.”

He describes the “healing power of daydreaming in existential situations,” a coping mechanism that helped him endure the unimaginable. Even so, he approached the writing with restraint, striving “to be cool and unemotional,” despite the weight of the memories.

As he recounts his life, Meron’s story becomes one of continual reinvention—each chapter more improbable than the last.

“A person who did not go to school between the age of 9 and 15… who started an academic career at 48… became a UN war crimes judge at 71… and became a published poet at the age of 95. Are these not miracles?”

The title of his memoir feels almost understated.

His professional life has been driven by a single, urgent mission: preventing future atrocities and protecting the vulnerable.

“I tried to choose to work so that Holocausts and Genocides will not be repeated… that children would not lose their childhoods and education and autonomy.”

Yet he is cleareyed about the limits of the institutions he served. Courts, he says, can only do so much.

“The promise of never again is mainly a duty of States and the international community, not just courts.”

Much of Meron’s legacy lies in shaping the legal frameworks that define modern international criminal law. He helped transform the skeletal principles left by Nuremberg into robust doctrines capable of prosecuting genocide, crimes against humanity, and wartime sexual violence.

“Fleshing out principles… especially on genocide, crimes against humanity and especially rape.”

His work helped ensure that atrocities once dismissed as collateral damage are now recognized as prosecutable crimes.

Even with these advances, Meron remains realistic about the limits of legal institutions.

“Courts tried to do their best, but this is largely the duty of States and their leaders.”

Justice, he suggests, is not only a legal project but a political and moral one—requiring courage from governments, not just judges.

Despite witnessing humanity at its worst, Meron refuses to surrender to despair. His outlook is grounded in history, tempered by experience, and sustained by a stubborn belief in progress.

“Reforms in the law and in human rights have often followed atrocities.”

He acknowledges that progress is uneven—“not linear,” as he puts it—but insists that hope is essential.

“We have ups and downs and a better day will come. We should work for it. Despair will not help.”

Judge Theodore Meron’s life is a testament to resilience, intellect, and moral clarity.

A Thousand Miracles is not simply a memoir of survival—it is a record of a life spent shaping the world’s understanding of justice, guided always by memory, principle, and the belief that even in humanity’s darkest hours, a better future remains possible.

Features

Gamification in Online Casinos: What Do Casino Online DudeSpin Experts Say

Gamification is one of the trends in modern game development. The technology allows players to interact with in-game elements and complete various tasks to earn additional rewards. Sites like casino online DudeSpin are eager to explore new technologies. Canadian players are particularly drawn to gamification for the opportunity to test their skills and have fun. Various development approaches allow for the implementation of much of this functionality already at this stage of development.

Core Elements of Gamification

Gamification is a technology that implements various elements to increase player attention. This mechanic not only attracts new users but also increases the time spent playing. This method rewards the most active players and also uses interactive elements that evoke certain associations and habitual actions.

Gamification elements include:

Achievement systems. Players earn special points and rewards for achieving certain goals. For example, unlocking a new level awards points and free spins on slot machines.

Leaderboards. Competitive rankings increase player attention and encourage active betting. Furthermore, healthy competition between participants improves their overall performance.

Progressive mechanics. Players consistently achieve higher results, which unlock additional privileges. Constant progression creates the effect of maximum engagement and attention to the user’s personality.

Challenges. Special quests and daily missions help players feel needed, and a structured goal system encourages active betting.

Sites like casino online DudeSpin utilize all these components to make players feel part of a unified, evolving system.

Psychological Appeal of Gamification

The key to gamification’s success is that every player wants to feel special and appreciated. A reward system stimulates dopamine, which creates additional rewarding gameplay experiences. This is how sites like casino online DudeSpin retain a loyal audience and build a strong community.

Stable player progress serves as a motivation to continue betting and unlocking new achievements. Furthermore, a certain level on the leaderboard provides an opportunity to showcase your skills and connect with others at your level. Personalized offers enhance the effect of this uniqueness, encouraging more active betting in games. Structured goals and achievements help players manage their time spent active, focusing only on activities that truly benefit them.

Canadian Perspective on Gamified Casino Experiences

Canadian casinos are using gamification techniques for a reason. They’re developing a legal and modern market that appeals to local audiences. Furthermore, operators like casino online DudeSpin operate in compliance with local laws, which fosters trust.

Another reason for gamification’s popularity is the localization of content. All games, prizes, and tournaments are tailored to the local market. A loyal community communicates in a clear language and interacts according to audience preferences.

Many casinos also integrate responsible options to help players manage their deposits and avoid overspending. This structure makes gamification attractive.

Finally, gamification is already a traditional element of gameplay in Canadian casinos, attracting new audiences and increasing loyalty among existing ones.

Technology evolves alongside new opportunities, and operators strive to offer the best benefits to their most active players. This interaction makes gamification a viable solution for gamblers. Leaderboards, achievements, and adaptive features are particularly popular with Canadian users due to their personalization.