Features

Interview with Daniel Levin – author of international best seller “Proof of Life”, the sensational true story of the hunt for a young man gone missing in Syria in 2012

By BERNIE BELLAN A couple of months back I had the opportunity to read and review an advance copy of a terrific new book titled “Proof of Life”, by Daniel Levin.

In it Levin tells the true story of a task he was given to try and find out what happened to a young man who disappeared in Syria during the early stages of what turned out to be a protracted struggle between the regime of Bashar Assad and the many different groups that emerged determined to fight him.

By now we know how incredibly vicious that fighting became – with all sides committing atrocities that shocked much of the world. Yet, despite the tremendous dangers he knew he would face in accepting his assignment, Levin was able to navigate some of the murkiest corners of the Middle East in pursuit of his goal.

Levin’s book was so completely riveting – and disturbing in many aspects, that when I was offered the opportunity to interview Levin himself, I immediately accepted. It took some time, however, to find a time where Daniel Levin could sit down and talk with me over the phone – about his life and his endlessly fascinating career which has involved his working in some of the world’s most dangerous areas.

Finally, on June 4, Levin was available – for what I originally thought was only going to be about 20 minutes, but when he told me that he actually had 45 minutes to spare, I took advantage to delve as much as I could into how he came to be doing what he does. I spoke with Levin, who was in his home somewhere in New York.

Levin’s early years took him all over the world

I had thought that what might follow would be a give and take, but in reality Levin operates in such a different world that would be so unfamiliar to most of us that he spent a good deal of his time explaining just what it is that he does. I began by saying to him: “Your background was as sort of as a negotiator – you were working to develop modes of democracy in states that had authoritarian-led governments. Is that correct?”

Rather than answer that question in a brief manner, however, Levin entered into a long and fairly complex explanation of what he does and how he ended up in the world of hostage negotiation, which is a byproduct of his primary work.

He began by informing me that he had read my review of his book, which, he said, was quite good, except that I had made one mistake. I had written that Levin was a “Swiss-born Jew”.

“I was actually Israeli-born,” he clarified – “in 1963. My father was an early founder generation – served in the Palmach, ended up going into politics, was close to Ben Gurion, became a diplomat, and in the mid-60s he was posted to Kenya – where my sister was born.

“We were there during the Six-Day War and after he returned – in 1969, his views diverged from those of his colleagues in the Labor Party. He favoured a negotiation with the Palestinians immediately – despite the Khartoum Resolution (which became famous for the “three nos: no peace with Israel, no recognition of Israel, no negotiations with Israel”), had a big clash with most of them, and decided to leave for a few years. And because my mother was from the Italian part of Switzerland, we moved to Switzerland in 1970. That’s how the Swiss angle started.

“We lived there for most of my school years – elementary and high school. After high school I came to the US, where I went to Yeshiva, also studied martial arts. I went back to Switzerland, went to law school, moved back to Israel in 1988, both to do my military service, also because I was working on my doctorate in law and my thesis was about clashes between religious and secular legal systems.

“I came to the States in 1992 – I’m basically anchored here since.

“The reason that I’m telling you all this is that my most of my work as a lawyer involved conflicts between different legal, religious, and political systems and how they can be reconciled.

“As an example, if you have a Jewish divorce that a secular judge has to evaluate for compliance with secular constitutional norms – does he just go into his American law – or his Swiss law or his French law, or does he look at the Jewish law and see whether it might provide suitable alternate solutions that would be more compliant with his secular law principles?

“That was my initial background and when I came to the States in the early 90s I did a post doctorate at Columbia, then ended up working in a large law firm, and most of our work was in developing countries, trying to develop their new financial markets and judicial systems. I did that for a few years until I decided I wasn’t interested in doing just the transactional part and I started my own law firm with some partners with the idea of initially helping countries – in Africa, South America, in the Middle East, help them emerge from poverty and high debt levels, and try to develop new political and economic structures.

“That was in the 90s. We developed essentially a development platform – at its core a non-World Bank approach. We didn’t just fly in experts and tell them what to do, but rather we developed a kind of knowledge platform – like a library, and we would provide that platform as a tool to local talent, to young professionals on the ground, and we would work with them to develop their own solutions.

Contacted by the Prince of Liechtenstein to help start a foundation

“That was the origin of our work and, around 2006 I was contacted by a head of state – a monarch in Europe, the Prince of Liechtenstein, who said ‘I really like your approach to development. What I’d like to do is start a not-for-profit foundation and you’ll use your methodology as a way to work in failed states, conflict zones, war torn areas, to help rebuild them by helping with the next generation of leaders to develop solutions that might work – so that, for example, if you go to a country like Yemen, which has been shattered by civil war and by tribalism – 187 tribes, can we figure out different political systems, different constitutional systems – rotation governments for example – not what you have in Israel right now, but rotations among tribes, and can those solutions work?’ ”

Levin continued: “We develop platform tools for training of next-generation leaders. We work with partners in the different regions. For Yemen, for example, we’re working with a partnership in Abu Dhabi. In Libya we’re working with a very high quality individual to develop a think tank outside of Libya, where we’re training young Libyans to take future leadership positions in the country.

“It’s not as if we’re coming into countries and telling people what their countries should look like. Our goal is to use our knowledge platform and our tools to help teams on the ground to develop their country based on their own preferences and traditions, but with the benefit of best practices from other countries and regions.”

Levin went on to describe the often painfully slow steps required in trying to develop democratic institutions within countries that have not had any sort of tradition of democracy. He said that his foundation tries to find young, uncorrupted individuals – not the sons and daughters of ruling elites, he emphasized – and teach them about such things as constitutions and a judicial system that will remain uncorrupted.

I wondered whether it was even possible to find – and train, young individuals, inside the countries themselves where Levin’s foundation might be attempting to develop basic democratic norms.

He admitted that, in many cases, it involves having to take individuals outside of their countries for training. “But,” he cautioned, “there is no way to replace the presence in the country itself. There is no way, for example, to avoid having to go to Syria in those early years and interact with people there.”

Levin added though, that the goal, “at some point, is to take the core team that you’re working with out of the country – and take them for further training, in the Syrian case – to Lebanon, because it’s just not safe for your own staff and for the individuals who you’re wanting to train to leave them there.”

As much as one may harbour notions of glamorous international diplomacy – jetting into world hot spots – such as how American diplomat Richard Holbrooke was famous for doing, Levin said, he wanted to make sure to dispel any idea that what he and his small team do is anything except very hard work – often leading to total disappointment.

With that in mind, Levin launched into a more detailed explanation how he became involved in what was, at the time, a civil war in Syria between the Assad regime and a large number of factions opposed to that regime.

“That became the beginning of my work and, since the Arab Spring (which began in 2011), we’ve been so heavily involved in war zones – in Syria, for example, which is the basis of the book, that we were involved not just in developing these solutions, but in mediating between the war sides. This was early in the war – when it wasn’t clear how the war was going to end or that the regime would end up with the upper hand following the Russian intervention in 2015.

How Levin became a hostage negotiator in Syria

“It was in that context that I was approached by various families (including of the young man who went missing in Syria), who said: ‘You’re active in Syria, you’re active in Libya, can you help us find our missing son, our missing husband? That was the entry into the world of hostage negotiations.”

At that point I said to Levin that I was glad he provided context for how he ended up involved in trying to find out what happened to one young man in particular in Syria. I said to him that anyone who would read “Proof of Life” would find themselves plunged right into the harrowing tale of Levin being immersed in a very dangerous pursuit of information – without knowing all that much about Levin himself. In fact, I said to him, if he hadn’t made clear at the outset of the book that what the reader was about to read was all true, I’m sure that a great many readers would think that it’s a work of fiction.

I said to Levin that “the next question that would probably come to mind to any Jewish reader, for sure, and probably almost anyone for that matter, is how does a Jew – and you didn’t pretend to be anything other, gain entrée into all these countries where one would think a Jew – never mind an Israeli, would not exactly be received with open arms. Was it a problem at all?”

Never hid the fact he was a Jews – although he didn’t advertise his being Israeli-born

Levin responded: “There are a number of elements to that. First of all I never have hidden the fact that I’m Jewish; I did not advertise the fact that I’m Israeli. I have multiple citizenships, but I am Israeli-born. Israeli was my first one (citizenship) and the one I’m most attached to. I view myself as Israeli; I served in the army there, my father served in the army there; I was in combat multiple times. I didn’t advertise that and that is why I am very careful how I describe myself in the book.

“I do show how I recorded and documented everything in the book, but I didn’t want the book to be too much about myself. I am the protagonist in this, but I really wanted to tell the story of this war economy (in Syria) and some of its victims (some girls who were forced into prostitution in Dubai became subjects of Levin’s interest during the course of his investigation).

“As to my own background and my ‘Israeliness’, it shines through – and some of the things that I did in the army were tools that I needed to navigate these 20 days (Levin spent in pursuit of his goal) and some other scenarios.

Levin answered: “I never hide my Israeliness; I just don’t advertise it. If someone asked me I wouldn’t lie about it. Anything I’m telling you now – unless I say something is off the record, you can go ahead and write about.”

As for how Levin recorded actual conversations (which are often quoted verbatim in the book – and some of them are extremely frightening as he is able to get certain characters to open up about some terrifying incidents in which they have been involved, including murder) – “The way I recorded (conversations),” Levin explained, “was primarily with my phone. I created a short cut to my home screen. I didn’t have to open my phone; I just had to tap a button and start recording, and I had a separate recording device.

“Whenever I was able to record a conversation, I did that. There were several situations in which I was unable to do that – especially the night in Beirut where I had to surrender all my electronic devices. In those cases, I would take notes whenever I could and I’m careful in the book to indicate when I’m writing down from memory, also when the memory of others was different from the way I remembered moments, so that I try to be as honest as I can.

Levin said he “wanted to add (in response to my question how Levin was able to navigate some of the murkiest areas of the world in the Middle East) that I had lived in Africa as a kid, and one of the languages I learned was Swahili – and Swahili has a very strong Arabic base. It later helped me when I learned Arabic, much, much later in my professional career. So, part of the answer to your question is I was able to blend in, rather than stand out as Jewish or Israeli.”

I wanted to switch tacks from talking about “Proof of Life” to Levin’s experience as a negotiator in other venues. “Have you been asked by various governments to get involved in behind the scenes negotiations at other times?” I wondered.

“Yes – there are two angles to this. Usually – in the case of hostages, I get approached by families and then I coordinate with governments if it’s relevant – with the intelligence community or diplomats, but generally I get approached by families because they’re not getting anywhere with their home governments.

“With respect to mediation between the sides in the Middle East (and it’s usually the Middle East where Levin gets involved, he noted) it’s on our foundation’s platform either to mediate a conflict or to provide what I call a ‘Track 3 diplomacy’ channel, which is a very informal – with full plausible deniability, communication channel, so that the sides that might not otherwise be talking – and there are several of those in the Middle East, as you can imagine, have a way to communicate – not so much to sign some sort of peace agreement – that’s an illusion, but just, for example, to prevent unintended escalations.

“Very often Israel is one side of this equation – and an action gets misinterpreted as an intended act of aggression, and there’s a real need to have indirect conversation and make sure that it doesn’t trigger consequences. It’s something that I get very involved in as part of my daily work.”

I asked: “Given that, is there anything you’d like to say about the recent war between Israel and Hamas? If you had been involved, was there some sort of expertise that you might have been able to offer that could have prevented that war?”

“The short answer to your question,” Levin offered, “is no.

“I’ve been involved in escalations both between Israel and Palestinians and countries surrounding Israel. The issue in all the clashes between Israel and Hamas – as well as Israel in Lebanon, is: ‘Are you trying to mediate this for the sake of finding a solution or are you trying simply to mitigate the suffering or are you merely going through the motions based on your own particular identity – even if you look at the recent clash and, even if you try to avoid the particular tribal or political affiliation – Jewish, not Jewish, conservative, progressive – those types of discussions tend to be tedious and unproductive, because once people have identified who they are, their positions tend to flow from there without much flexibility or room for negotiation.

“My job is different because, in the case of Israel and Hamas, these types of escalations have clear political benefits for very specific individuals or parties. If you take the recent one, it’s very clear that Netanyahu’s political fortunes had reached an end…and obviously with this most recent case, it started with a very clear provocation by right wing Israeli groups in Sheikh Jarrah. If you want to start into a discussion about who’s been in the Middle East longer – 3,000 years, 5,000 years – I’m not interested in that.

“What I’m interested in is that people are suffering in the region and you have to make a decision whether you’re working toward a political solution or not. This particular escalation benefited Netanyahu – at least very temporarily, and it benefited Hamas. Hamas itself was starting to lose control over the street in Gaza. I’ve been to Gaza many times and Gaza today is not Gaza of 20 years ago – before Israel pulled out – in 2005. It’s also not Gaza of ten years ago.

Youth in Gaza feel oppressed by Hamas

“In Gaza today you have a youth fighting battles that were born after those conflicts of 20-25 years ago and they don’t feel the same allegiance to Hamas; they feel oppressed by Hamas. Hamas is starting to lose some of its authority and needs to resort to more and more oppression to stay in power. They had an interest in this escalation because they can present themselves as the protector of Al Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem and responding to the provocation of Israeli policemen and soldiers with boots in the mosque. Those kinds of games and provocations have been going on for decades. There’s really nothing for me to do because no one is really trying to find a solution, through mediation or by other means – yes, there’s mediation for a cease-fire, but you’re never getting at the root of the conflict. I want to get involved when there’s a genuine desire to go beyond just repeating the same mistakes.”

I wanted to return to Levin’s experience in Syria, which, after all, led him to write “Proof of Life”. I asked him whether his involvement in mediating between various sides – both pro-regime and anti-regime, would also have led him to get involved with “Islamist groups” as well?

He answered: “No, not at the time. If you look at the timeline of the war in Syria, you have the uprising starting in 2011 – and it’s really starting over an increase in bread and food prices. And, instead of responding intelligently, they (the Assad regime) responded brutally – like many countries in the Arab Spring they started to slaughter children – 15-year-old boys spraying on a wall ‘We want cheaper food’ would be beaten to death in a police van, and that triggered huge uprisings and an insurgency started in September 2011.

“My involvement was primarily in 2012-13 in a mediating capacity. It was when the UN was trying to negotiate a cease-fire. It was before the rise of the Islamists in 2014, which also led to those gruesome executions of American and other Western hostages. It was also before the Russian intervention in September 2015, which completely tipped the war in favour of the regime.”

Levin also reminded me that there were no Islamist insurgents in 2011 in Syria, although Assad did release thousands of Islamists from prison at the very beginning of the insurgency – exactly the same way Saddam Hussein did during the American invasion of Iraq – and those released prisoners became the core of ISIS.

“At the point that we were involved, it was to see if we could deescalate the violence; the regime was not gaining the upper hand, the opposition was organized under the Free Syrian Army, and there were – within each camp, really genuine requests to see if there was a way that we could end this slaughter.

“When the whole thing collapsed – in 2014 and 15, we aborted our project there and stopped any form of mediation because the regime was no longer interested in a peaceful, negotiated solution. But I still remained involved in several matters in Syria, including the searches for missing persons and hostages.”

Levin’s current focus is on Libya and Yemen

I asked: “You say you’ve been involved in countries in Africa and the Middle East that could be described either as failed states or states attempting to emerge from authoritarian rule. Are there any other countries in which you’ve been involved?”

Levin said: “Yes, certainly in a development capacity, in Central America, Southeast Asia – Malaysia, Indonesia, but in terms of real conflict negotiation in the sense that I’ve been describing (during this conversation), it’s been primarily in north Africa, the Middle East, and the Gulf – from Yemen to Libya, even some aspects of the Iran conflict.”

“Libya and Yemen?” I said. “Those can best be described as failed states run by gangs and warlords. Is there anything you can offer as a ray of hope for the futures of those two countries?”

“Yes, I think so,” Levin replied. “Our foundation is actively involved in both those countries. In Libya, there is some hope – not so much because of the current temporary prime minister – (whose name is Dbeibeh), but rather because there is a weakening of the warlords, particularly the warlord in the east of the country, whose name is Khalifa Haftar, who is supported primarily by Egypt and the United Arab Emirates, and Russia. There is some form of reconciliation there, also encouraged and supported by European countries which finally recognized that the only way to stem the flow of African refugees coming to Europe through Libya was to have some form of stability in Libya.

“Yemen,” Levin observed, “is a very tribal society – some 187 different tribes – very fragmented, fragmented religiously between Sunni and Shia – fragmented between south and north. Yemen has been in a tenuous state since the 50s and every outside party that has tried to get involved in Yemen has failed. It’s sort of the Arab Vietnam. It’s a very complicated place to try to turn into a functioning state.

“There are very legitimate questions – and we’re working with groups, trying to figure out whether Yemen should be one nation or should it be a confederation of states or even tribes? Yemen was also a terrible mistake by the Saudi Crown Prince who thought he could prove his manhood with a quick win in Yemen and didn’t realize he would face the same fate as Nasser did 65-70 years ago (when Egypt’s then President Nasser also intervened in Yemen).

“So, Yemen is in far worse shape than Libya, I would say in answer to your question.”

As much as reading “Proof of Life” led me to want to find out quite a bit more about Daniel Levin, talking to him about the book and his career led me to ask him whether there might be more books in the works.

He said that in September a book called “Milena’s Promises” will be released in German (“Milenas Versprechen”). “It’s a crime story, a dialogue between an Israeli woman and a young man in the U.S. in the form of an email exchange. It’s all about the question of God’s existence and omnipotence, the suffering of innocent people, and the meaning of being a “chosen” people.”

“Proof of Life”, which was released on May 18th, has garnered a myriad of sensational reviews – including my own. As a result, I can hardly wait to read “Milena’s Promises” once it comes out in English.

Features

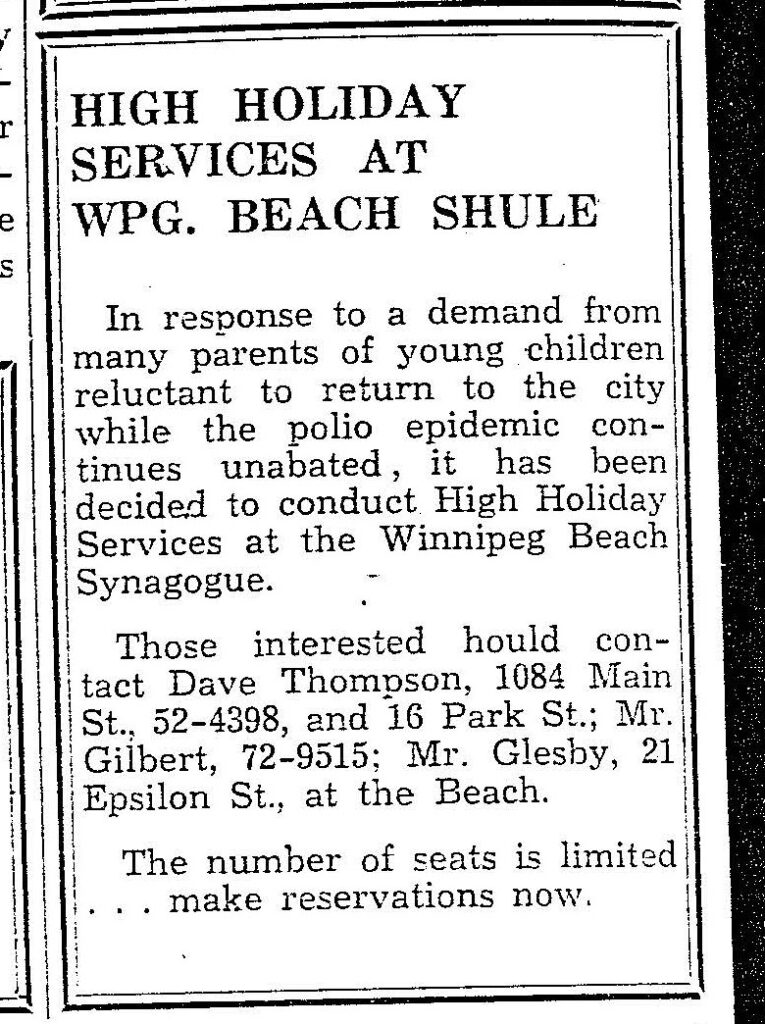

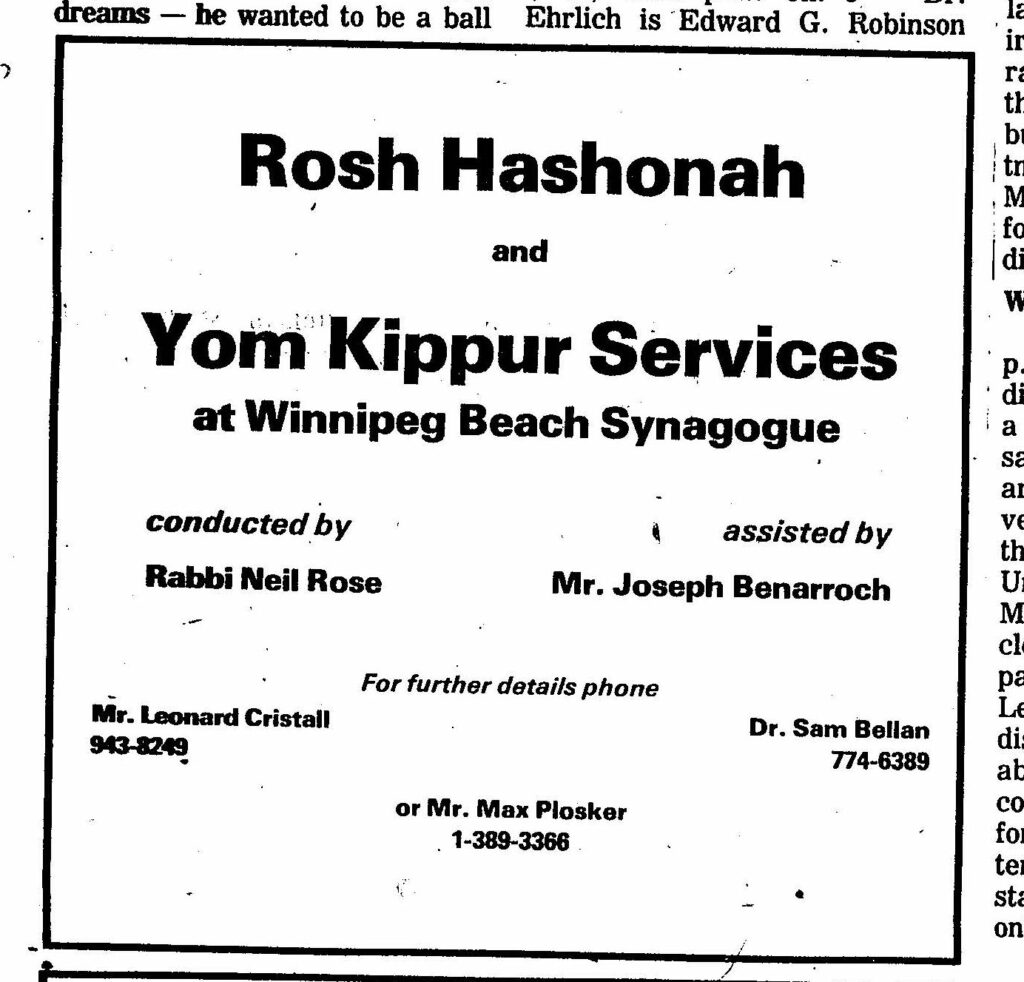

History of the Winnipeg Beach Synagogue: 1950-2025

By BERNIE BELLAN The history of the Winnipeg Beach Synagogue is a fascinating one. We have had several articles over the years about the synagogue in The Jewish Post & News.

In June 2010 I wrote an article for The Jewish Post & News upon the 60th anniversary of the synagogue’s opening. Here are the opening paragraphs from that article:

“Sixty years ago a group of Winnipeg Beach vacationers decided that what their vacation area lacked was a synagogue. As it happened, a log cabin one-room schoolhouse in the Beausejour area happened to be available.

“In due course, the log cabin was relocated to the corner of Hazel and Grove in Winnipeg Beach, where it stayed for 48 years.”

In December 1994 my late brother, Matt, wrote a story about the spraying of antisemitic grafitti on the synagogue which, at that time, was still situated at its original location on the corner of Hazel and Grove in the town of Winnipeg Beach:

“Two 16-year-olds spraypainted slogans like ‘Die Jews,’ ‘I’ll kill you Jews,’ and other grafitti in big letters on the beach synagogue.

“Jim Mosher, a news reporter for the Interlake Spectator in Gimli, said last Halloween’s vandalism against the synagogue wasn’t the first. In the late 1980s, he claimed, it was spraypainted with swastikas.

“Jack Markson, a longtime member of the Winnipeg Beach Synagogue, last week also said he could remember finding anti-Semitic grafitti spraypainted on the synagogue ‘a few years ago,’ and at least twice in the 1970s, when the cottage season was over.”

My 2010 article continued: “In 1998 the Town of Winnipeg Beach informed the members of the synagogue that the building would have to be hooked up to the town’s sewer and water system. Rather than incur the cost of $3-4,000, which was thought to be ‘prohibitive,’ according to longtime beach synagogue attendee Laurie Mainster, synagogue goers looked elsewhere for a solution.

“As a result, the board of Camp Massad was approached and asked whether the synagogue might be relocated there, with the understanding that the synagogue would be made available to the camp at any time other than what were then Friday evening and Saturday morning services.

“Over the years the ‘beach synagogue’ had come to be a very popular meeting place for summertime residents of Winnipeg Beach and Gimli. In fact, for years minyans were held twice daily, in addition to regular Saturday morning services. Of course, in those years Winnipeg Beach was also home to a kosher butcher shop.

“While the little synagogue, which measured only 18 x 24 feet, has gone through several transformations, including the move to Camp Massad, and the opening up to egalitarian services in 2007 (The move to egalitarian services was as much a practical necessity as it was a nod to the equality of women – the only Kohen present at the time was a woman!), it has always remained cramped at the best of times.

“In recent years the synagogue has seen the addition of a window airconditioner (although to benefit from it, you really have to be sitting just a few feet away), as well as a fridge that allows synagogue attendees to enjoy a regular Saturday morning Kiddush meal following the service.

“According to Laurie Mainster, the Saturday morning service has continued to be popular, even though many of the attendees now drive in from Winnipeg, as they have sold the cottages they once maintained.

“On the other hand, one of the side benefits to being located on Camp Massad’s grounds has been an infusion of young blood from among the camp counsellors.

“Since there is no longer a rabbi available to conduct services (Rabbi Weizman did lead services for years while he had a cottage at the beach), those in attendance now take turns leading the services themselves.

“Anyone may attend services and, while there are no dues collected, donations are welcome. (Donations should be made to the Jewish Foundation of Manitoba, with donors asked to specify that their donations are to be directed to the beach synagogue.)

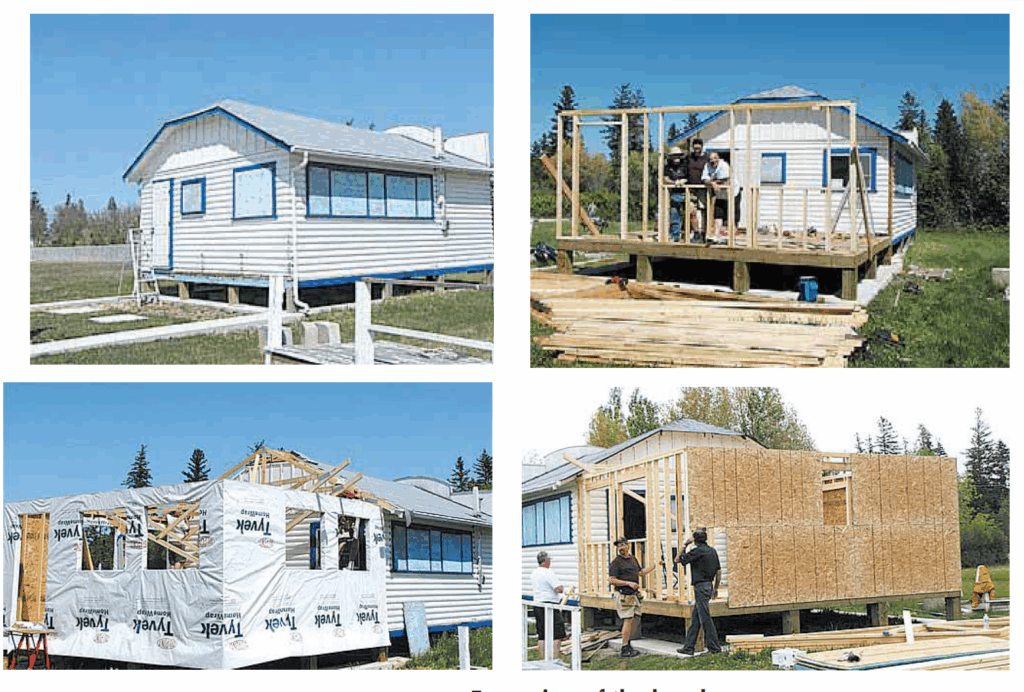

“Mainster also says that the beach synagogue is now undergoing an expansion, which will be its first in 60 years. An entirely new space measuring 16 x 18 feet is being added – one that will allow for a real Kiddush area. (Until now, a table has been set up in the back of the synagogue and synagogue goers would help themselves to the buffet that is set up each Saturday during the summer. While pleasant enough, it will certainly be more comfortable to have an actual area set aside for the Saturday afternoon after service lunch.)

“As for dress, longtime attendee Abe Borzykowski (in an article written by Sharon Chisvin for the Free Press in 2007) remarked that ‘I don’t think there are many synagogues where people can attend in shorts, T-shirts and sandals and not feel out of place.’ “

As mentioned in that 2010 article, the beach synagogue at that time was about to undergo an extensive remodelling. Here is an article from a January 2011 issue that describes that remodelling process. The article was written by Bernie Sucharov, who has been a longtime member of the beach synagogue:

“The Hebrew Congregation of Winnipeg Beach made a major change to the synagogue this past summer. With the help of many volunteers, Joel Margolese being the project manager, the synagogue was expanded and an addition was built to handle the overflow crowds, as well as to add more space for the kiddush following services.

“The volunteers spent many Sundays during the summer months building the addition. Bad weather caused many delays, but finally the addition was completed one week before the official summer opening.

“The volunteers were: Joel Margolese, Gordon Steindel, Sheldon Koslovsky, Viktor Lewin, Harvey Zabenskie, Nestor Wowryk, Kevin Wowryk, Victor Spigelman, Jerry Pritchard, and David Bloomfield.

“On Sunday, June 25, 2010 a special ceremony was held to affix a mezzuzah to the front entrance door. Gordon Steindel had the honour of affixing the mezzuzah, which was donated by Sid Bercovich and Clarice Silver.

“Refreshments and food for the day were prepared by Phyllis Spigelman, also known as our catering manager. Throughout the summer, Phyllis, Lenore Kagan and other friends prepared the food for our kiddush.

“A sound system was donated by Arch and Brenda Honigman in memory of their father, Sam Honigman z”l. “The system was installed by Joel Margolese and Stevan Sucharov. This will allow the overflow crowd to hear the service in the new addition.

“There were also generous donations of 50 chumashim and an air conditioner. The chumashim were donated by Gwen, Sheldon and Mark Koslovsky. The air conditioner in the new addition was donated by Joel and Linda Margolese.

“The official opening of the synagogue for the summer took place on July 3, 2010. We had an overflow crowd of 70+ people.”

Since that 2010 major addition to the synagogue, it has also added a wheelchair ramp (although I’ve been unable to ascertain exactly when the ramp was built). Also, the synagogue also has its own outdoor privy now. (Attendees used to have to use facilities in Camp Massad.)

And, as already noted in a previous article, in recognition of the synagogue’s 75th anniversary – on August 2nd members of the synagogue will be holding a 75th anniversary celebration.

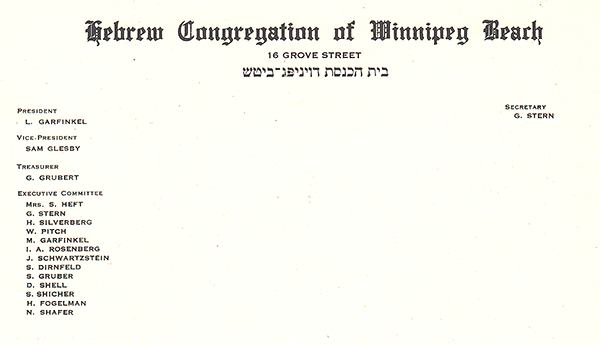

As part of the celebration anyone who is a descendant or relative of any of the original members of the first executive committee is invited to attend the synagogue that morning.

If you are a relative please contact Abe Borzykowski at wpgbeachshule@shaw.ca or aborzykowski@shaw.ca to let Abe know you might be attending.

Features

Winnipeg Beach Synagogue about to celebrate 75th anniversary

By BERNIE BELLAN (July 13) In 1950 a group of cottage owners at Winnipeg Beach took it upon themselves to relocate a one-room schoolhouse that was in the Beausejour area to Winnipeg Beach where it became the beach synagogue at the corner of Hazel and Grove.

There it stayed until 1998 when it was moved to its current location at Camp Massad.

On August 2nd members of the synagogue will be holding a 75th anniversary celebration.

As part of the celebration anyone who is a descendant or relative of any of the original members of the first executive committee (as seen in the photo here) is invited to attend the synagogue that morning.

If you are a relative please contact Abe Borzykowski at wpgbeachshule@shaw.ca or aborzykowski@shaw.ca to let Abe know you might be attending or for more information about the 75th anniversary celebration.

We will soon be publishing a story about the history of the beach synagogue, which is something I’ve been writing about for over 25 years.

Features

Kinzey Posen: CBC Winnipeg’s former “go-to guy”

By GERRY POSNER If former Winnipegger Lawrence Wall was the CBC go-to guy in Ottawa, CBC Winnipeg had its own version of a go-to guy for many years with none other than the very well known Kinzey Posen. Of course, many readers will recognize that name from his career with Finjan, the Klezmer group so famous across Canada and beyond. It has been written about Posen and his wife Shayla Fink that they have been involved in music since they got out of diapers. And, as an aside, their love and ability in music has now been transmitted to the next generation as in their son, Ariel Posen (but that’s another story).

Kinzey Posen (not to be confused with Posner, or maybe we are to be confused, but who knows for sure?), was a graduate of Peretz School, having attended there from nursery right until Grade 7, graduating in1966. That was followed by Edmund Partridge and West Kildonan Collegiate. Musically, he was in large part self taught. However, he did have some teachers along the way. After moving to Vancouver – from 1974-78, he had the chance to study acoustic classical bass with a member of the Vancouver Symphony Orchestra. When Kinzey lived in Vancouver, he also worked as a jazz musician.

Upon returning to Winnipeg, Kinzey enrolled as a mature student at the University of Winnipeg, where he obtained a Bachelor of Urban Studies degree. Although the degree was in no way connected to the career that followed, his attending the University of Winnipeg was critical to his connecting with the CBC. Why? you ask. Kinzey had a position after graduation working for the Institute of Urban Studies. While there, he met someone who invited him to work for the Department of Continuing Education as one of their program directors. At the time the Department of Continuing Education was located at 491 Portage Avenue, which was also known as the TJ Rice Building. The CBC also leased some space in the same building. According to Kinzey, the CBC part of the building “included HR, different shows and other support offices. Continuing Education was located in the basement and main floor and that’s where I worked.”

KInzey had long had an interest in the CBC, which made the fact that the CBC had some offices in the same building where he was working serendipitous. That Kinzey might be interested in visiting the CBC was not an accident. As a young boy he had a nightly connection to CBC, as it was his ritual to listen to CBC Radio (as well as all sorts of other radio stations across the USA) on his transistor radio every night in bed. He became enamoured of one particular CBC host, Bill Guest, so that when going to sleep, he imagined that he was Guest doing interviews with imaginary guests. That dream of working for CBC became a reality when he had a chance to do a one week gig with Jack Farr’s network program.

Kinzey took a week off from his Continuing Education job and spent five days at the CBC. That week was a training session for Posen, as he had to create ideas, research, pre-interview, write the script, and set up the studio for Farr’s interview. He was almost in his dream job – although not quite – since it was only for one week. His opportunity, however, came in 1988, when he was offered a one-year term as a production assistant – the lowest guy on the ladder, for a show called “ Simply Folk,” with the late Mitch Podolak as the host. Although he was indeed at the bottom as far as those working on the show were concerned, he took a chance and gave his notice to the U of W. The rest is history. In his new job, Kinzey learned how to become a producer. Lucky for him, at the end of the year, when the person he replaced was supposed to come back, she never returned (just like the song, “MTA,” by the Kingston Trio). At that point, Kinzey was hired full time at the CBC.

Kinzey was a fixture at the CBC for 27 years. During those years, Kinzey had the chance to work with Ross Porter, a respected former CBC host and producer, also with Karen Sanders – on the “Afternoon Edition.” One aspect of Kinzey’s job on the Afternoon Edition was to come up with ideas, mix sound effects, arrange interviews and music, to create a two-hour radio experience. In addition, he covered jazz and folk festivals and, as a result, was exposed to some of the best musicians in the world. With Ross Porter in the 1990s, he worked on a network jazz show called “ After Hours,” which was on from 8-10 PM five nights a week. Kinzey was involved with writing the scripts, picking the music, and recording the shows, as well as editing them and then presenting them to the network for playback.

Of course, over his career, Kinzey had many memorable moments. He told me about one of them. The story revolved around the National Jazz Awards one year in particular. The awards were to be broadcasted after the National News which, in those days, began much earlier in the evening, and were over by 8:00 pm. The legendary Oscar Peterson was lined up to play a half hour set at the awards, starting at 7:30. But, as Kinzey told me, Oscar Peterson had a “hate on” for the CBC ecause one of his recorded performances was wrongly edited and he refused to appear on CBC under any circumstances. As the time neared 8:05 PM, which was when the CBC was to begin its broadcast of the jazz awards, it became apparent that Oscar was not going to finish on time. As the producer of the awards show, Kinzey was tasked with telling Oscar Peterson to wrap it up and get off the stage. There was Kinzey Posen, a huge fan of Oscar Peterson, now faced with the prospect of telling Oscar – while he was still playing – with 500 people in the audience, to stop and get off the stage. Not often was or is Kinzey Posen frozen, but that was one such moment. There was one loud “Baruch Hashem” from Kinzey when Oscar completed his set literally just in time.

Clearly, Kinzey was part of a very successful run with After Hours as it was on the air for 14 years. It was easily one of the most popular shows on CBC Radio 2, and a winner of several broadcasting awards. Kinzey also played a major role in producing a two part documentary about legendary guitarist Lenny Breau.

When After Hours ended, Posen became one of the contributing producers to Canada Live and specialized in producing live radio specials for the network, such as the Junos, for CBC Radio One and Two. Needless to say, his career planted Posen in the world of some top notch musicians, including his time spent working with Robert Plant (Led Zeppelin), Dave Brubeck, Randy Bachman, Chantal Kreviazuk and a list of prominent names in the Canadian, American and European music spheres. Locally, the CBC came to refer to Kinzey as the Jewish expert. I would add music expert to that title.

After his 27 year run at the CBC – and before he fully retired, Kinzey went on to work for the Rady JCC as a program director for a year and a half. Of course, to say that Kinzey Posen is retired is a major contradiction in terms. You really can’t keep him down and he has his hand in a variety of programs and projects – most of which he remains silent about, as is his style.

When I realized the full depth and talent of Kinzey Posen, I quickly concluded that he must certainly be related to me. Even if he isn’t, I now tell people he is.