Features

Jewish Life in Canada, seen through the eyes of William Kurelek

By IRENA KARSHENBAUM In December, as I was running up a steep hill in the bitter Calgary cold, which is not as bitter as the Winnipeg cold, I was cursing myself for not having covered my brilliant head with a woollen scarf.

Wearing my 1916 prairie costume, underneath a 25 year-old sheep skin coat that now passes for historic, I scaled the hill at Heritage Park while worrying I might suffer a heart attack triggered by too much vigorous movement in the frigid cold. The angle of the hill dropped down and my brisk pace turned into a slow, penguin-like waddle to steady myself on the ice.

My eyes looked up and facing me, as if on the palm of my hand, was a scene from another time. The sun danced on the dazzling, white snow and in the near distance, across the railroad tracks, stood a little, yellow false-front building, once called the Montefiore Institute, framed by naked, trembling trees, and where I was headed. A horse-drawn wagon turned the corner and slowly crossed along the path. Not being satisfied with just savouring the moment, I grabbed my phone. An image emerged on my screen, worthy of a cozy children’s book, or a William Kurelek painting.

My vision was prescient.

That afternoon, on my volunteer shift as an interpreter, in the kitchen of the Montefiore Institute, which also served as the cheder, I looked through the sideboard buffet that housed a small library. I was searching for a Hanukkah story to read to the children when my eyes rested on Jewish Life in Canada, by William Kurelek and Abraham Arnold.

I flipped the pages of this old book and even though I was familiar with Kurelek’s work, I suddenly could see that the artist’s paintings depicting early Canadian Jewish life looked an awful lot like us, the costumed interpreters bringing Jewish life, to life, to the guests visiting the restored 1916 prairie synagogue. I was momentarily confused, was I a subject of a William Kurelek painting that had magically come alive?

Not wanting the other interpreters to think I am some kind of a book thief (which, of course, I am!) I announced, loudly, that I will be borrowing the book to write my latest story about an out-of-print book — Bernie didn’t know this yet — with promises to return it.

At home, I read the book. Divided into two parts, the first half being the works of William Kurelek (1927-1977), with his own writings about each painting, and the second by, Abraham Arnold (1922-2011) — who served as the founding Executive Director of the Jewish Historical Society of Western Canada — and who contributed a series of essays about various aspects of Jewish life, that read more like a text book.

Kurelek credits “the two Abes of Winnipeg” — Arnold and Abe Schwartz — in his introduction for giving him the support he needed to bring the book project to life.

Kurelek recounts how, in 1973, the idea for the book emerged and was meant as an expression of thanks to the Jewish community for his success as an artist. It was Winnipeg-native, Avrom Isaacs (1926-2016), who first discovered the artist and took the risk of exhibiting his work, a break Kurelek desperately needed having for ten years tried “in vain on my own for recognition.” Isaacs gave Kurelek two opening nights, the first being sponsored by a Jewish women’s organization (he doesn’t say which one) that also bought a few of his pieces. He states that in fact his first art patrons were Jewish and only later, “followed by those of British origin.”

Jewish Life in Canada contains 16 of Kurelek’s paintings, all of which as indicated in the book, are held in the collection of a Mr. and Mrs. Jules Loeb, and was published by Hurtig Publishers of Edmonton in 1976. The book is out of print and unavailable, except through maybe a lucky find at a used book store or on Amazon. My search for a used copy, surprisingly, brought up information that a new edition of a Jewish Life in Canada, this time with writing by Sarah Milroy, will be published by Goose Lane Editions of Fredericton in May of 2023.

Through his paintings, Kurelek, born to a Ukrainian family in Whitford, Alberta, depicts Jewish life in Canada from the east coast, “Jewish Doctor’s Family Celebrating Passover in Halifax,” to the prairies in “Baker’s Family Celebrating the Sabbath in Edmonton” and “Jewish Wedding in Calgary” set in front of the original House of Jacob synagogue, to the west with, “General Store in Vancouver Before World War One.”

Having converted to Catholicism in adulthood, Kurelek doesn’t shy away from religious subjects displaying remarkable knowledge about Judaism’s religious practices. In “Yom Kippur” he shows what the Holy Day looks like with congregants immersed deep in prayer, men wearing their tallis, women praying in the women’s balcony. He paints a white parochet explaining that, “White, symbol of purity, is the dominant colour of this solemn day.” He used Toronto’s Kiever Synagogue as the basis for this work.

Kurelek shows how Jews toiled in their new land with works like “Morosnick’s Market, Dufferin Street, Winnipeg,” “Teperman’s Wrecking Firm in Toronto” with men sorting scrap metal, men sewing in “Jews in the Clothing Business in Winnipeg” and “Jewish Scrap Collector Questioned by a Toronto Policeman,” a composite work inspired by Kurelek’s memories and multiple photographs including one from Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan.

Four of Kurelek’s paintings depict Jewish farming life.

In “Pioneering at Edenbridge, Saskatchewan,” Kurelek writes about the history of the colony, which was settled in 1906 by 20 Jewish immigrants, originally from Lithuania, who decided to leave their new-found home in South Africa for a second migration to fertile farm lands along the Carrot River. It is this painting, with its horse-drawn wagon and wooden homes in the distance, that reminded me of the view I encountered at Heritage Park that December day.

In “Bender Hamlet, the Farming Colony that Failed,” Kurelek displays good knowledge of Jewish prairie history, listing all the farm colonies of Saskatchewan and Alberta, even mentioning my beloved Montefiore where the Montefiore Institute originally stood, also Camper, Pine Ridge and Bender Hamlet of Manitoba. He paints Bender Hamlet, founded in 1903, with a few, far away, grey buildings set against a vast sky and yellow, grassy fields littered with rocks. The inspiration for the painting, he notes, came from Abe Schwartz, who gave Kurelek his great-aunt’s diary describing her life farming in North Dakota. Kurelek explains how he incorporated pieces of the diary into the picture frame, “I want to convey the idea that these memories are like voices in the wind as it sighs through the thistles of the overgrown fields and through the chinks of abandoned buildings.”

Kurelek’s Jewish Life in Canada is more than a thanks to the Jewish community, but a gift of memory that reveals a life that once was to future generations.

Irena Karshenbaum, founder of the project that gifted the restored Montefiore Institute to Calgary’s Heritage Park, volunteers as an interpreter in the synagogue and writes. www.irenakarshenbaum.com

Features

Israel’s Arab Population Finds Itself in Dire Straits

By HENRY SREBRNIK There has been an epidemic of criminal violence and state neglect in the Arab community of Israel. At least 56 Arab citizens have died since the beginning of this year. Many blame the government for neglecting its Arab population and the police for failing to curb the violence. Arabs make up about a fifth of Israel’s population of 10 million people. But criminal killings within the community have accounted for the vast majority of Israeli homicides in recent years.

Last year, in fact, stands as the deadliest on record for Israel’s Arab community. According to a year-end report by the Center for the Advancement of Security in Arab Society (Ayalef), 252 Arab citizens were murdered in 2025, an increase of roughly 10 percent over the 230 victims recorded in 2024. The report, “Another Year of Eroding Governance and Escalating Crime and Violence in Arab Society: Trends and Data for 2025,” published in December, noted that the toll on women is particularly severe, with 23 Arab women killed, the highest number recorded to date.

Violence has expanded beyond internal criminal disputes, increasingly affecting public spaces and targeting authorities, relatives of assassination targets, and uninvolved bystanders. In mixed Arab-Jewish cities such as Acre, Jaffa, Lod, and Ramla, violence has acquired a political dimension, further eroding the fragile social fabric Israel has worked to sustain.

In the Negev, crime families operate large-scale weapons-smuggling networks, using inexpensive drones to move increasingly advanced arms, including rifles, medium machine guns, and even grenades, from across the borders in Egypt and Jordan. These weapons fuel not only local criminal feuds but also end up with terrorists in the West Bank and even Jerusalem.

Getting weapons across the border used to be dangerous and complex but is now relatively easy. Drones originally used to smuggle drugs over the borders with Egypt and Jordan have evolved into a cheap and effective tool for trafficking weapons in large quantities. The region has been turning into a major infiltration route and has intensified over the past two years, as security attention shifted toward Gaza and the West Bank.

The Negev is not merely a local challenge; it serves as a gateway for crime and terrorism across Israel, including in cities. The weapons flow into mixed Jewish-Arab cities and from there penetrate the West Bank, fueling both organized crime and terrorist activity and blurring the line between them.

The smuggling of weapons into Israel is no longer a marginal criminal phenomenon but an ongoing strategic threat that traces a clear trail: from porous borders with Egypt and Jordan, through drones and increasingly sophisticated smuggling methods, into the heart of criminal networks inside Israel, and in a growing number of cases into lethal terrorist operations. A deal that begins as a profit-driven criminal transaction often ends in a terrorist attack. Israeli police warn that a population flooded with illegal weapons will act unlawfully, the only question being against whom.

The scale of the threat is vast. According to law enforcement estimates, up to 160,000 weapons are smuggled into Israel each year, about 14,000 a month. Some sources estimate that about 100,000 illegal weapons are circulating in the Negev alone.

Israeli cities are feeling this. Acre, with a population of about 50,000, more than 15,000 of them Arab, has seen a rise in violent incidents, including gunfire directed at schools, car bombings, and nationalist attacks. In August 2025, a 16-year-old boy was shot on his way to school, triggering violent protests against the police.

Home to roughly 35,000 Arab residents and 20,000 Jewish residents, Jaffa has seen rising tensions and repeated incidents of violence between Arabs and Jews. In the most recent case, on January 1, 2026, Rabbi Netanel Abitan was attacked while walking along a street, and beaten.

In Lod, a city of roughly 75,000 residents, about half of them Arab, twelve murders were recorded in 2025, a historic high. The city has become a focal point for feuds between crime families. In June 2025, a multi-victim shooting on a central street left two young men dead and five others wounded, including a 12-year-old passerby. Yet the killing of the head of a crime family in 2024 remains unsolved to this day; witnesses present at the scene refused to testify.

The violence also spilled over to Jewish residents: Jewish bystanders were struck by gunfire, state officials were targeted, and cars were bombed near synagogues. Hundreds of Jewish families have left the city amid what the mayor has described as an “atmosphere of war.”

Phenomena that were once largely confined to the Arab sector and Arab towns are spilling into mixed cities and even into predominantly Jewish cities. When violence in mixed cities threatens to undermine overall stability, it becomes a national problem. In Lod and Jaffa, extortion of Jewish-owned businesses by Arab crime families has increased by 25 per cent, according to police data.

Ramla recorded 15 murders in 2025, underscoring the persistence of lethal violence in the city. Many victims have been caught up in cycles of revenge between clans, often beginning with disputes over “honour” and ending in gunfire. Arab residents describe the city as “cursed,” while Jewish residents speak openly about being afraid to leave their homes

Reluctance to report crimes to the authorities is a central factor exacerbating the problem. Fear of retaliation by families or criminal organizations deters victims and their relatives from coming forward, contributing to a clearance rate of less than 15 per cent of all murders. The Ayalef report notes that approximately 70 per cent of witnesses refused to cooperate with police investigations, citing doubts about the state’s ability to provide protection.

Violence in Arab society is not just an Arab sector problem; it poses a direct and serious threat to Israel’s national security. The impact is twofold: on the one hand, a rise in crime that affects the entire population; on the other, the spillover of weapons and criminal activity into terrorism, threatening both internal and regional stability. This phenomenon reached a peak in 2025, with implications that could lead to a third intifada triggered by either a nationalist or criminal incident.

The report suggests that along the Egyptian and Jordanian borders, Israel should adopt a technological and security-focused response: reinforcing border fences with sensors and cameras, conducting aerial patrols to counter drones, and expanding enforcement activity.

This should be accompanied by a reassessment of the rules of engagement along the border area, enabling effective interdiction of smuggling and legal protocols that allow for the arrest and imprisonment of offenders. The report concludes by emphasizing that rising violence in cities, compounded by weapons smuggling in the Negev, is eroding Israel’s internal stability.

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.

Features

The Chapel on the CWRU Campus: A Memoir

By DAVID TOPPER In 1964, I moved to Cleveland, Ohio to attend graduate school at Case Institute of Technology. About a year later, I met a girl with whom I fell in love; she was attending Western Reserve University. At that time, they were two entirely separate schools. Nonetheless, they share a common north-south border.

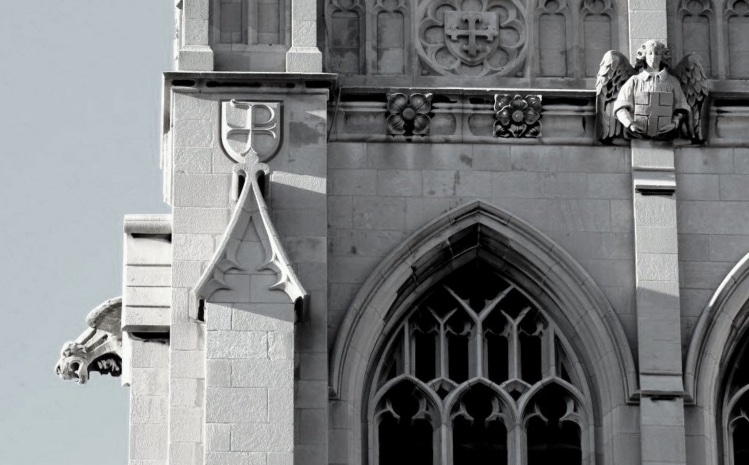

Since Reserve was originally a Christian college, on that border between the two schools there is a Chapel on the Reserve (east) side, with a four-sided Tower. On the top of the Tower are three angels (north, east, & south) and a gargoyle (west); the latter therefore faces the Case side. Its mouth is a waterspout – and so, when it rains, the gargoyle spits on the Case side. The reason for this, I was told, is that the founder of Case, Leonard Case Jr., was an atheist.

In 1968, that girl, Sylvia, and I got married. In the same year the two schools united, forming what is today still Case Western Reserve University (CWRU). I assume the temporal proximity of these two events entails no causality. Nevertheless, I like the symbolism, since we also remain married (although Sylvia died almost 6 years ago).

Speaking of symbolism: it turns out that the story told to me is a myth. Actually, Mr. Case was a respected member of the Presbyterian Church. Moreover, the format of the Tower is borrowed from some churches in the United Kingdom – using the gargoyle facing west, toward the setting sun, to symbolize darkness, sin, or evil. It just so happens that Case Tech is there – a fluke. Just a fluke.

We left Cleveland in 1970, with our university degrees. Harking back to those days, only once during my six years in Cleveland, was I in that Chapel. It was the last day before we left the city – moving to Winnipeg, Canada – where I still live. However, it was not for a religious ceremony – no, not at all. Sylvia and I were in the Chapel to attend a poetry reading by the famed Beat poet, Allen Ginsberg.

My final memory of that Chapel is this. After the event, as we were walking out, I turned to Sylvia and said: “I’m quite sure that this is the first and only time in the entire long history of this solemn Chapel that those four walls heard the word ‘fuck’.” Smiling, she turned to me and said, “Amen.”

This story was first published in “Down in the Dirt Magazine,”

vol, 240, Mars and Cotton Candy Clouds.

Features

MyIQ: Supporting Lifelong Learning Through Accessible Online IQ Testing

Strong communities are built on education, curiosity, and meaningful conversation. Whether through schools, cultural institutions, or family discussions at the dinner table, intellectual growth has always played a central role in local life. Today, digital tools are expanding the ways individuals explore personal development — including the ability to assess cognitive skills online.

One such platform is MyIQ, an online service that allows users to take a structured IQ test and receive detailed results. As more people seek accessible educational resources, platforms like MyIQ are becoming part of broader conversations about learning, intelligence, and personal growth.

Why Cognitive Self-Assessment Matters in Local Communities

Education as a Community Value

Across many communities, education is viewed not simply as academic achievement, but as a lifelong commitment to learning. Parents encourage curiosity in their children. Students strive for academic excellence. Adults pursue professional growth or personal enrichment.

Cognitive assessment tools offer a structured way to reflect on skills such as:

- Logical reasoning

- Numerical understanding

- Pattern recognition

- Verbal analysis

These are foundational abilities that influence academic performance and everyday problem-solving.

Encouraging Constructive Dialogue

Online discussions about intelligence often spark meaningful reflection. When handled responsibly, IQ testing can serve as a starting point for conversations about:

- Study habits

- Educational opportunities

- Strengths and challenges

- The balance between genetics and environment

MyIQ fits into this dialogue by providing structured results and transparent explanations.

What Is MyIQ?

MyIQ is an online IQ testing platform designed to measure reasoning abilities across multiple cognitive domains. Unlike casual internet quizzes, MyIQ presents an organized testing experience followed by contextualized reporting.

A public Reddit discussion that references the platform can be viewed here: MyIQ

In this thread, users openly discuss their results and reflect on possible influences such as family background and personal development. The transparency of this conversation highlights organic engagement and reinforces the platform’s credibility.

How the MyIQ Test Is Structured

Multi-Domain Assessment

MyIQ evaluates intelligence across several structured areas:

Logical Reasoning

Assesses the ability to analyze information and draw conclusions.

Mathematical Reasoning

Measures comfort with numbers, sequences, and quantitative logic.

Pattern Recognition

Evaluates the ability to detect visual or numerical relationships.

Verbal Comprehension

Tests interpretation and understanding of written material.

This approach ensures that results are not based on a single narrow skill set but on a broader cognitive profile.

Clear and Contextualized Results

After completing the assessment, users receive:

- An overall IQ score

- Percentile ranking

- Explanation of score range

- Identification of stronger and weaker domains

For individuals unfamiliar with IQ metrics, percentile ranking offers helpful context. Instead of viewing a number in isolation, users can understand how their results compare statistically.

Such clarity supports responsible interpretation and reduces misunderstanding.

Comparing MyIQ to Informal IQ Quizzes

| Feature | MyIQ | Informal Online Quiz |

| Structured Categories | Yes | Often Random |

| Percentile Explanation | Included | Rare |

| Balanced Reporting | Yes | Minimal |

| Community Discussion | Active | Limited |

| Professional Presentation | Yes | Varies |

For readers interested in credible digital services, this structured approach stands out.

Responsible Use of IQ Testing

It is important to emphasize that IQ scores represent specific cognitive abilities measured under standardized conditions. They do not define:

- Character

- Work ethic

- Creativity

- Compassion

- Community involvement

Many successful individuals contribute meaningfully to their communities regardless of standardized test scores. MyIQ presents results as informational tools rather than labels, encouraging thoughtful reflection.

The Role of Community Feedback

Trust in digital services increasingly depends on transparent user experiences. The Reddit thread linked above demonstrates:

- Voluntary sharing of results

- Open questions about interpretation

- Constructive discussion about intelligence and background

- Honest reflection on expectations

Such dialogue aligns with community values that prioritize conversation and shared understanding.

When users openly analyze their experiences, it adds authenticity beyond promotional claims.

Who Might Benefit from MyIQ?

Students

Students preparing for academic milestones may find value in understanding their reasoning strengths.

Parents

Parents curious about cognitive development may use structured assessments as conversation starters about learning habits.

Professionals

Adults seeking self-improvement can use IQ testing as one of many personal development tools.

Lifelong Learners

Individuals who enjoy intellectual exploration may simply appreciate structured insight into how they process information.

Digital Tools and Modern Learning

Community life increasingly intersects with technology. From online education platforms to digital libraries, accessible learning resources are expanding opportunities.

MyIQ fits into this landscape by offering:

- Online accessibility

- Clear and structured format

- Immediate feedback

- Transparent reporting

This accessibility allows individuals to explore cognitive assessment privately and thoughtfully.

Intelligence: Genetics and Environment

The Reddit discussion highlights a common question: how much of intelligence is influenced by genetics versus environment?

While scientific research suggests both play roles, IQ testing should not be viewed as deterministic. Education quality, nutrition, mental stimulation, and life experiences all contribute to cognitive development.

MyIQ does not claim to define destiny. Instead, it offers a snapshot — a moment of measurement within a broader life journey.

Final Thoughts: MyIQ as a Tool for Reflection

Communities thrive when curiosity is encouraged and learning is valued. In this spirit, structured self-assessment tools can serve as part of a healthy intellectual culture.

MyIQ provides an organized, transparent, and discussion-supported approach to online IQ testing. With contextualized results and visible community dialogue, the platform demonstrates credibility and accessibility.

For readers interested in exploring their reasoning abilities — whether for academic, professional, or personal reasons — MyIQ offers a modern digital option aligned with the principles of education, reflection, and lifelong growth.

Used thoughtfully, it becomes not a label, but a conversation starter — one that supports curiosity, awareness, and continued learning within any engaged community.