Features

“Judenrein” posits what might happen if a right-wing conspiracy in the United States – and a cooperative president, came together

“Judenrein”

By “Harold Benjamin”

Self-published in 2020, but available on Amazon in either e-book or hard copy format.

Reviewed by BERNIE BELLAN

A while back I received an email from someone named “Harold Benjamin” (which, it turned out, was a pseudonym).

In that email Mr. Benjamin told me that he had written a book titled “Judenrein”.

The title immediately grabbed my attention as I knew it referred to the German term coined by the Nazis meaning “Jew free”. Here’s a brief description of the book’s plot, as given on Amazon:

“Zack Gurevitz has had a checkered past. A Yeshiva boy, turned Green Beret, turned junkie, excommunicated by his one-time faith and now the potential savior of people he doesn’t even like.

“As a white supremacist movement stealthily takes the reins of power in America, it is again the Jews who are made out as scapegoats. Stripped of wealth and citizenship, they are made to live in 21st century ghettos that hark back to a sinister and murky past that many had thought would never return.

“But things are about to get much worse. With the revealing of a planned terror attack that will place the blame firmly at Jewish feet and condemn millions to death, Zack is contacted by Jewish leaders in Detroit, begging for his help.

“Reluctantly he agrees and before long he is mired in a conspiracy that will have far reaching consequences for his country, the Jewish population and even his own sanity.

“As the clock ticks down, can Zack find a way to avert a looming disaster? Who is behind the conspiracy? And can he really trust anyone?”

Earlier this year a four-part television series based on a Phillip Roth novel titled “The Plot Against America” was aired on HBO (and can still be seen either on Shaw or MTS TV. That show speculates about what might have happened had the anti-Semite Charles Lindbergh become president of the United State in 1940.

We are living in turbulent times and, although it is hard to say definitively whether anti-Semitism is now as great a concern for Jews more than any other time since the Holocaust, there have been many indicators of late that it should be, although I’m going to add the proviso that I refuse to accept that’s the case in Winnipeg.

I have deliberately avoided stoking the fears of readers of this paper unnecessarily by printing a large number of the stories that we receive via email almost daily which, if we printed them all, would no doubt lead anyone to conclude that Jews are under fierce attack almost everywhere. Yes, in certain areas of North America, especially where Orthodox Jews live in large numbers in specific neighbourhoods, it is becoming increasingly dangerous for Jews, but I would argue that simply isn’t the case here in Winnipeg – much as certain individuals would love to scare us into thinking anti-Semitism is rampant in this city.

Notwithstanding my reluctance to succumb to the notion that Jews everywhere are under attack, when the author of “Judenrein” asked me whether I might like him to send me a copy of his self-published book, I thought to myself: “Why not? It might be worth taking a look.”

I admit I was somewhat hesitant, however, to plunge into the book – not because I was shying away from the subject matter, but simply because we’ve had quite a few self-published books sent our way and, quite frankly, almost all of them should have been edited by a professional editor.

Now, “Judenrein” certainly falls into the category of books that should have been more carefully edited, but when it comes to a riveting plot – well, I just couldn’t stop reading this book. I don’t know anything about Harold Benjamin beyond what he sent me when I asked him to write a brief autobiographical blurb. Here’s what he wrote:

“Here’s a little bio: Harold Benjamin is the pen name of a 50-something Jewish writer who lives in the American midwest (sic. “midwest” should be capitalized). Most of his professional work involves corporate copywriting. He grew up in the suburbs of New York city (sic. “city” should be capitalized.) and was educated on the east coast (sic. “east coast” should be capitalized.) He’s of Latvian, Polish and Lithuanian descent. All four of his grandparents were born outside of the US, three of them in the 19th century.”

As you can see by my use of the term “sic.”, just within the short blurb that Benjamin sent me, his writing could use some careful editing. If you’re a stickler for grammar, capitalization, also, to a certain extent -syntax as well, “Judenrein” can be a little annoying. (Why don’t self-publishing authors send their books to someone to correct those sorts of mistakes I always wonder after I’ve read a book that should have been thoroughly edited.)

Yet, don’t let my somewhat petty criticism on this point deter you in the least from considering buying this book. It’s a spellbinder of the first order.

I should also mention that last year I was introduced to the writing of Daniel Silva at one of the sessions of the book club this paper sponsors jointly with the Rady JCC. I should be somewhat embarrassed to admit that I hadn’t heard of Daniel Silva prior to that particular meeting of the book club but, wow – I’m hooked on his books now. By the way, in case you’re also wondering who Silva is, he’s probably the world’s foremost spy thriller writer right now – having written 19 novels, with an Israeli spy named Gabriel Allon as his recurrent hero.

To return to “Judenrein” – as explained in the blurb I quoted, the story revolves around a plot to put the Jewish population in America into ghettos – and eventually expel them.

It’s not too hard to imagine a right-wing conspiracy of that sort actually being planned these days, given the level of anti-Semitic discourse so prevalent on the internet. What “Judenrein” successfully posits moreover, is how a conspiracy of that insidious sort could be successfully translated into reality.

And that’s where Harold Benjamin has done some masterful research. Within the framework of his plot, there are several ingredients that come together that lead to the gradual erosion of the civil rights of Jews, and the one that is key is the election of a right-wing president who is all too willing to abandon any notion of civil liberties.

Does that sound familiar? Now, I’m not going to turn this into yet another denunciation of Donald Trump, but “Judenrein” comes along at a time when divisions in America have never been starker and where the president is actively promoting those divisions.

Have Jews been targeted by Trump in the same way that he has targeted Mexicans, for instance, and arguably, anyone else who isn’t white? The president in “Judenrein”, who only goes by the initials “P.K.”, has a more clearly delineated contempt for Jews, but it is in his willingness to serve as the dupe of more intelligent right-wingers – all of whom are in the military, by the way, that his interests and the interests of a small group of very determined military men are aligned.

In point of fact, however, of late, it’s been senior members of the military who have admonished Trump for his expressed desire to use the military to quell civilian disturbances. Yet, one wonders the extent to which lower ranking members of the military would actually be in agreement with what Trump wanted to do – a point which becomes important in “Judenrein” in explaining how, under the right circumstances, right wing members of the military might readily join forces with right wing militias in persecuting Jews and other minority groups.

What happens in “Judenrein” – as the blurb from Amazon notes, is that the hero of this book who, though seriously flawed, rises to superspy status in short order – something, I suppose is a prerequisite for most spy novels these days.

Zack Gurevitz starts off as a drug addicted mess trying to get himself off heroin at a methadone clinic. How someone in that particular state can eventually rise to the level of extraordinary superhero really requires a total suspension of belief but, just as Gabriel Allon in Daniel Silva’s spy novels can overcome any obstacle, Zack Gurevitz manages to escape every nasty predicament in which he finds himself – and, believe me, there are enough close encounters that this book could be turned into an ongoing serial the way the Batman TV show of the 60s would leave you hanging on at the end of every episode.

Is it plausible that a recovering drug addict can be beaten viciously in one chapter, then miraculously recover within a few hours only to escape his captors and turn the tables on them – over and over again?

Of course not – but Benjamin knows how to build suspense and adds enough plot twists to keep the reader’s attention riveted.

Along the way he slips in a female FBI agent by the name of Matthews who, although she doesn’t become Zack’s love interest (disappointingly, for me at least. Come on – what’s a good spy thriller worth if it doesn’t have some gratuitous sex in it?), is eventually persuaded that there is a massive conspiracy afoot and that the FBI has become complicit in enabling it to move forward.

Since the author of this book didn’t actually reveal to me what his true background is, you either have to credit him with having done stellar research about various locations in the U.S. northeast, including certain buildings that do actually exist, along with a detailed knowledge of weaponry or, he himself was involved in employment that would have let him be privy to those details, all of which lend an air of authenticity to the storyline.

One final word about “Judenrein”: Although it’s a self-published book and available only on Amazon, there are already a fair number of reviews about this book on Amazon. To be honest, the reviews might be from friends or family of the author because they’re unanimous in heaping praise on this book – yet some of them offer thoughtful observations about how timely this book is at this point in American history.

When I asked Harold Benjamin how one might be able to buy his book he sent me this link: https://www.amazon.com/Judenrein-Dystopian-Thriller-Harold-Benjamin-ebook/dp/B086BRZDPF/ref=sr_1_4?dchild=1&keywords=judenrein&qid=1588353541&sr=8-4

Features

Japanese Straightening/Hair Rebonding at SETS on Corydon

Japanese Straightening is a hair straightening process invented in Japan that has swept America.

Features

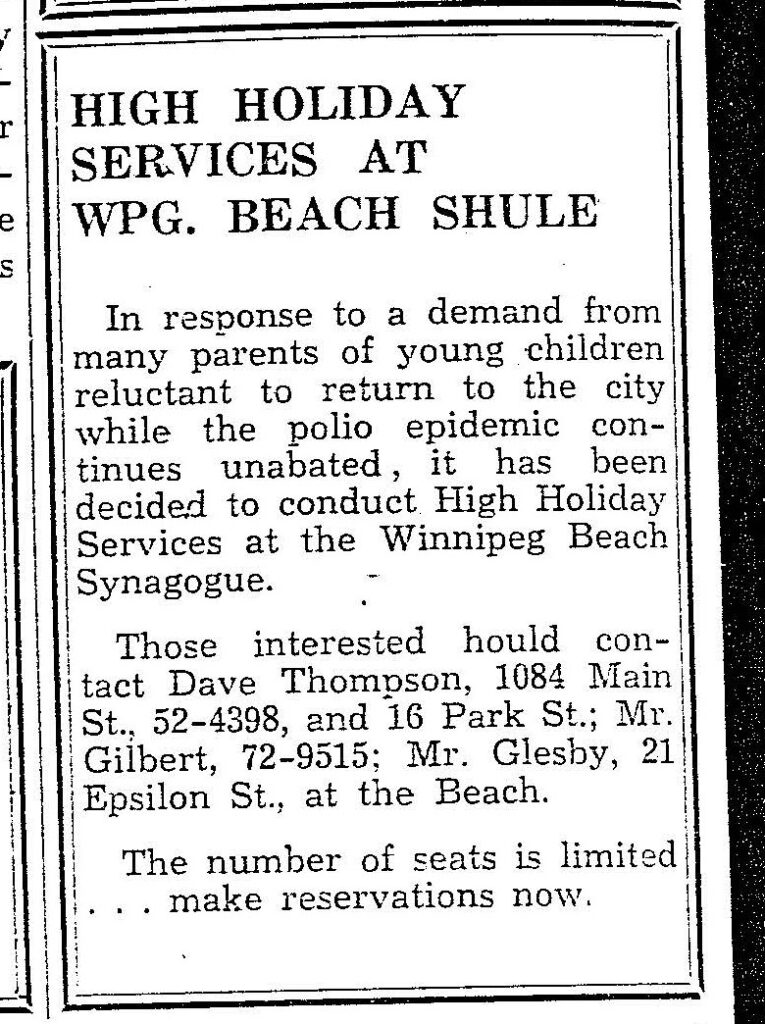

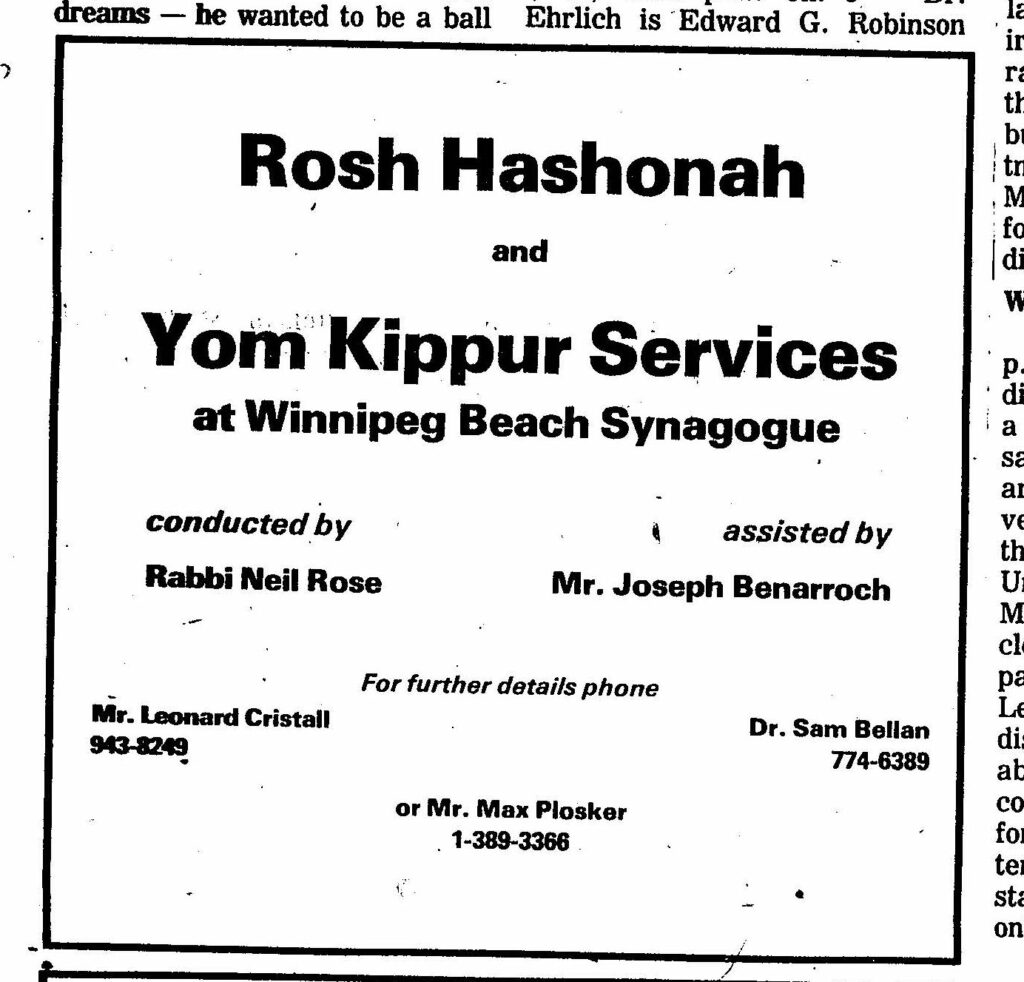

History of the Winnipeg Beach Synagogue: 1950-2025

By BERNIE BELLAN The history of the Winnipeg Beach Synagogue is a fascinating one. We have had several articles over the years about the synagogue in The Jewish Post & News.

In June 2010 I wrote an article for The Jewish Post & News upon the 60th anniversary of the synagogue’s opening. Here are the opening paragraphs from that article:

“Sixty years ago a group of Winnipeg Beach vacationers decided that what their vacation area lacked was a synagogue. As it happened, a log cabin one-room schoolhouse in the Beausejour area happened to be available.

“In due course, the log cabin was relocated to the corner of Hazel and Grove in Winnipeg Beach, where it stayed for 48 years.”

In December 1994 my late brother, Matt, wrote a story about the spraying of antisemitic grafitti on the synagogue which, at that time, was still situated at its original location on the corner of Hazel and Grove in the town of Winnipeg Beach:

“Two 16-year-olds spraypainted slogans like ‘Die Jews,’ ‘I’ll kill you Jews,’ and other grafitti in big letters on the beach synagogue.

“Jim Mosher, a news reporter for the Interlake Spectator in Gimli, said last Halloween’s vandalism against the synagogue wasn’t the first. In the late 1980s, he claimed, it was spraypainted with swastikas.

“Jack Markson, a longtime member of the Winnipeg Beach Synagogue, last week also said he could remember finding anti-Semitic grafitti spraypainted on the synagogue ‘a few years ago,’ and at least twice in the 1970s, when the cottage season was over.”

My 2010 article continued: “In 1998 the Town of Winnipeg Beach informed the members of the synagogue that the building would have to be hooked up to the town’s sewer and water system. Rather than incur the cost of $3-4,000, which was thought to be ‘prohibitive,’ according to longtime beach synagogue attendee Laurie Mainster, synagogue goers looked elsewhere for a solution.

“As a result, the board of Camp Massad was approached and asked whether the synagogue might be relocated there, with the understanding that the synagogue would be made available to the camp at any time other than what were then Friday evening and Saturday morning services.

“Over the years the ‘beach synagogue’ had come to be a very popular meeting place for summertime residents of Winnipeg Beach and Gimli. In fact, for years minyans were held twice daily, in addition to regular Saturday morning services. Of course, in those years Winnipeg Beach was also home to a kosher butcher shop.

“While the little synagogue, which measured only 18 x 24 feet, has gone through several transformations, including the move to Camp Massad, and the opening up to egalitarian services in 2007 (The move to egalitarian services was as much a practical necessity as it was a nod to the equality of women – the only Kohen present at the time was a woman!), it has always remained cramped at the best of times.

“In recent years the synagogue has seen the addition of a window airconditioner (although to benefit from it, you really have to be sitting just a few feet away), as well as a fridge that allows synagogue attendees to enjoy a regular Saturday morning Kiddush meal following the service.

“According to Laurie Mainster, the Saturday morning service has continued to be popular, even though many of the attendees now drive in from Winnipeg, as they have sold the cottages they once maintained.

“On the other hand, one of the side benefits to being located on Camp Massad’s grounds has been an infusion of young blood from among the camp counsellors.

“Since there is no longer a rabbi available to conduct services (Rabbi Weizman did lead services for years while he had a cottage at the beach), those in attendance now take turns leading the services themselves.

“Anyone may attend services and, while there are no dues collected, donations are welcome. (Donations should be made to the Jewish Foundation of Manitoba, with donors asked to specify that their donations are to be directed to the beach synagogue.)

“Mainster also says that the beach synagogue is now undergoing an expansion, which will be its first in 60 years. An entirely new space measuring 16 x 18 feet is being added – one that will allow for a real Kiddush area. (Until now, a table has been set up in the back of the synagogue and synagogue goers would help themselves to the buffet that is set up each Saturday during the summer. While pleasant enough, it will certainly be more comfortable to have an actual area set aside for the Saturday afternoon after service lunch.)

“As for dress, longtime attendee Abe Borzykowski (in an article written by Sharon Chisvin for the Free Press in 2007) remarked that ‘I don’t think there are many synagogues where people can attend in shorts, T-shirts and sandals and not feel out of place.’ “

As mentioned in that 2010 article, the beach synagogue at that time was about to undergo an extensive remodelling. Here is an article from a January 2011 issue that describes that remodelling process. The article was written by Bernie Sucharov, who has been a longtime member of the beach synagogue:

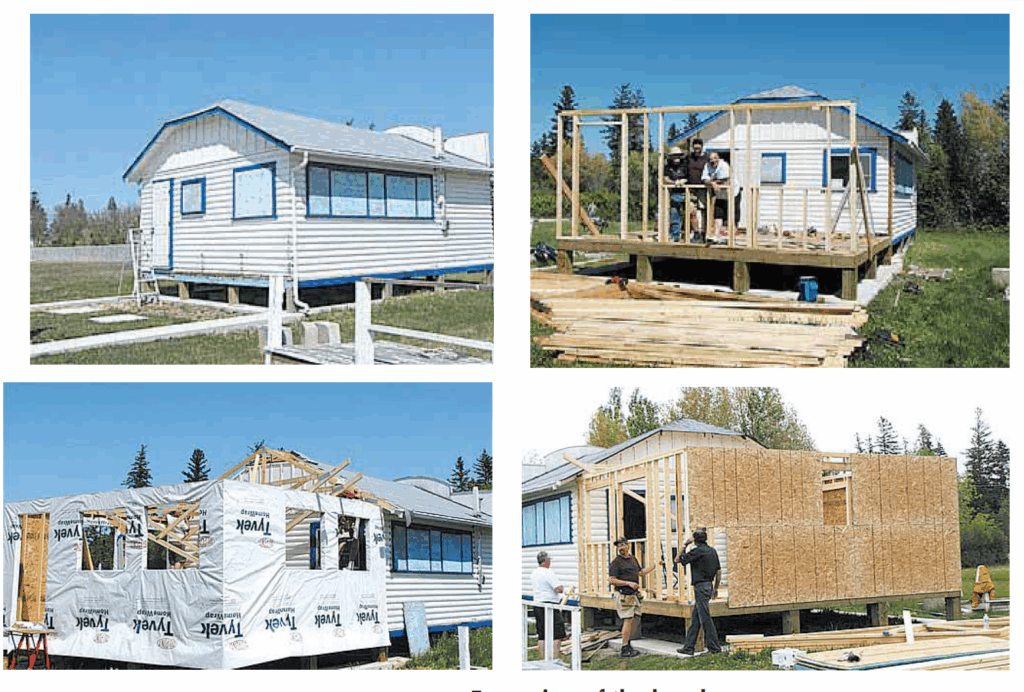

“The Hebrew Congregation of Winnipeg Beach made a major change to the synagogue this past summer. With the help of many volunteers, Joel Margolese being the project manager, the synagogue was expanded and an addition was built to handle the overflow crowds, as well as to add more space for the kiddush following services.

“The volunteers spent many Sundays during the summer months building the addition. Bad weather caused many delays, but finally the addition was completed one week before the official summer opening.

“The volunteers were: Joel Margolese, Gordon Steindel, Sheldon Koslovsky, Viktor Lewin, Harvey Zabenskie, Nestor Wowryk, Kevin Wowryk, Victor Spigelman, Jerry Pritchard, and David Bloomfield.

“On Sunday, June 25, 2010 a special ceremony was held to affix a mezzuzah to the front entrance door. Gordon Steindel had the honour of affixing the mezzuzah, which was donated by Sid Bercovich and Clarice Silver.

“Refreshments and food for the day were prepared by Phyllis Spigelman, also known as our catering manager. Throughout the summer, Phyllis, Lenore Kagan and other friends prepared the food for our kiddush.

“A sound system was donated by Arch and Brenda Honigman in memory of their father, Sam Honigman z”l. “The system was installed by Joel Margolese and Stevan Sucharov. This will allow the overflow crowd to hear the service in the new addition.

“There were also generous donations of 50 chumashim and an air conditioner. The chumashim were donated by Gwen, Sheldon and Mark Koslovsky. The air conditioner in the new addition was donated by Joel and Linda Margolese.

“The official opening of the synagogue for the summer took place on July 3, 2010. We had an overflow crowd of 70+ people.”

Since that 2010 major addition to the synagogue, it has also added a wheelchair ramp (although I’ve been unable to ascertain exactly when the ramp was built). Also, the synagogue also has its own outdoor privy now. (Attendees used to have to use facilities in Camp Massad.)

And, as already noted in article previously posted to this site (and which you can read at Beach Synagogue about to celebrate 75th anniversary), in recognition of that occasion, on August 2nd members of the synagogue will be holding a 75th anniversary celebration.

As part of the celebration anyone who is a descendant or relative of any of the original members of the first executive committee is invited to attend the synagogue that morning.

If you are a relative please contact Abe Borzykowski at wpgbeachshule@shaw.ca or aborzykowski@shaw.ca to let Abe know you might be attending.

Features

Kinzey Posen: CBC Winnipeg’s former “go-to guy”

By GERRY POSNER If former Winnipegger Lawrence Wall was the CBC go-to guy in Ottawa, CBC Winnipeg had its own version of a go-to guy for many years with none other than the very well known Kinzey Posen. Of course, many readers will recognize that name from his career with Finjan, the Klezmer group so famous across Canada and beyond. It has been written about Posen and his wife Shayla Fink that they have been involved in music since they got out of diapers. And, as an aside, their love and ability in music has now been transmitted to the next generation as in their son, Ariel Posen (but that’s another story).

Kinzey Posen (not to be confused with Posner, or maybe we are to be confused, but who knows for sure?), was a graduate of Peretz School, having attended there from nursery right until Grade 7, graduating in1966. That was followed by Edmund Partridge and West Kildonan Collegiate. Musically, he was in large part self taught. However, he did have some teachers along the way. After moving to Vancouver – from 1974-78, he had the chance to study acoustic classical bass with a member of the Vancouver Symphony Orchestra. When Kinzey lived in Vancouver, he also worked as a jazz musician.

Upon returning to Winnipeg, Kinzey enrolled as a mature student at the University of Winnipeg, where he obtained a Bachelor of Urban Studies degree. Although the degree was in no way connected to the career that followed, his attending the University of Winnipeg was critical to his connecting with the CBC. Why? you ask. Kinzey had a position after graduation working for the Institute of Urban Studies. While there, he met someone who invited him to work for the Department of Continuing Education as one of their program directors. At the time the Department of Continuing Education was located at 491 Portage Avenue, which was also known as the TJ Rice Building. The CBC also leased some space in the same building. According to Kinzey, the CBC part of the building “included HR, different shows and other support offices. Continuing Education was located in the basement and main floor and that’s where I worked.”

KInzey had long had an interest in the CBC, which made the fact that the CBC had some offices in the same building where he was working serendipitous. That Kinzey might be interested in visiting the CBC was not an accident. As a young boy he had a nightly connection to CBC, as it was his ritual to listen to CBC Radio (as well as all sorts of other radio stations across the USA) on his transistor radio every night in bed. He became enamoured of one particular CBC host, Bill Guest, so that when going to sleep, he imagined that he was Guest doing interviews with imaginary guests. That dream of working for CBC became a reality when he had a chance to do a one week gig with Jack Farr’s network program.

Kinzey took a week off from his Continuing Education job and spent five days at the CBC. That week was a training session for Posen, as he had to create ideas, research, pre-interview, write the script, and set up the studio for Farr’s interview. He was almost in his dream job – although not quite – since it was only for one week. His opportunity, however, came in 1988, when he was offered a one-year term as a production assistant – the lowest guy on the ladder, for a show called “ Simply Folk,” with the late Mitch Podolak as the host. Although he was indeed at the bottom as far as those working on the show were concerned, he took a chance and gave his notice to the U of W. The rest is history. In his new job, Kinzey learned how to become a producer. Lucky for him, at the end of the year, when the person he replaced was supposed to come back, she never returned (just like the song, “MTA,” by the Kingston Trio). At that point, Kinzey was hired full time at the CBC.

Kinzey was a fixture at the CBC for 27 years. During those years, Kinzey had the chance to work with Ross Porter, a respected former CBC host and producer, also with Karen Sanders – on the “Afternoon Edition.” One aspect of Kinzey’s job on the Afternoon Edition was to come up with ideas, mix sound effects, arrange interviews and music, to create a two-hour radio experience. In addition, he covered jazz and folk festivals and, as a result, was exposed to some of the best musicians in the world. With Ross Porter in the 1990s, he worked on a network jazz show called “ After Hours,” which was on from 8-10 PM five nights a week. Kinzey was involved with writing the scripts, picking the music, and recording the shows, as well as editing them and then presenting them to the network for playback.

Of course, over his career, Kinzey had many memorable moments. He told me about one of them. The story revolved around the National Jazz Awards one year in particular. The awards were to be broadcasted after the National News which, in those days, began much earlier in the evening, and were over by 8:00 pm. The legendary Oscar Peterson was lined up to play a half hour set at the awards, starting at 7:30. But, as Kinzey told me, Oscar Peterson had a “hate on” for the CBC ecause one of his recorded performances was wrongly edited and he refused to appear on CBC under any circumstances. As the time neared 8:05 PM, which was when the CBC was to begin its broadcast of the jazz awards, it became apparent that Oscar was not going to finish on time. As the producer of the awards show, Kinzey was tasked with telling Oscar Peterson to wrap it up and get off the stage. There was Kinzey Posen, a huge fan of Oscar Peterson, now faced with the prospect of telling Oscar – while he was still playing – with 500 people in the audience, to stop and get off the stage. Not often was or is Kinzey Posen frozen, but that was one such moment. There was one loud “Baruch Hashem” from Kinzey when Oscar completed his set literally just in time.

Clearly, Kinzey was part of a very successful run with After Hours as it was on the air for 14 years. It was easily one of the most popular shows on CBC Radio 2, and a winner of several broadcasting awards. Kinzey also played a major role in producing a two part documentary about legendary guitarist Lenny Breau.

When After Hours ended, Posen became one of the contributing producers to Canada Live and specialized in producing live radio specials for the network, such as the Junos, for CBC Radio One and Two. Needless to say, his career planted Posen in the world of some top notch musicians, including his time spent working with Robert Plant (Led Zeppelin), Dave Brubeck, Randy Bachman, Chantal Kreviazuk and a list of prominent names in the Canadian, American and European music spheres. Locally, the CBC came to refer to Kinzey as the Jewish expert. I would add music expert to that title.

After his 27 year run at the CBC – and before he fully retired, Kinzey went on to work for the Rady JCC as a program director for a year and a half. Of course, to say that Kinzey Posen is retired is a major contradiction in terms. You really can’t keep him down and he has his hand in a variety of programs and projects – most of which he remains silent about, as is his style.

When I realized the full depth and talent of Kinzey Posen, I quickly concluded that he must certainly be related to me. Even if he isn’t, I now tell people he is.