Features

Light and the time of year

By SUSAN TURNER

In November, we left Daylight Saving time behind to return to Standard time. We had already been experiencing increasing darkness each day, which had started with the Autumn Equinox in late September, and that is continuing until the Winter Solstice in late December, shortly after Chanukah and just before Christmas.

The mantra guiding this bi-annual switch is ‘fall back/spring forward’. Either Saturday night October 31 or the next morning November 1, we moved the clocks both digital and analog back one hour. No problem with the phones or the computer, though, because they did it themselves by virtue of the intelligence of their circuits. Sunday, however, was confusing. Our tummies rumbled an hour early, and the dog puzzled about the delay in being fed. For a few days after the time change, many reported feeling a bit discombobulated.

The Winter Solstice signifies that we will have reached the shortest day of the year, the day with the least light and the most darkness. We then creep towards the Vernal Equinox near the end of March, when light of day and dark of night are equal. After that, the days gradually lengthen until the Summer Solstice in June, that special day. It is the lightest day of the year, and remains light well into the nighttime hours. But then, inexorably, it starts all over again, moving from light towards darkness. The equinoxes and solstices happen in the natural world, guided by the movement of the earth around the sun. We learn about them in school, we mark them on calendars, and the light associated with them is reflected in culture, art, and in aspects of religion.

In Jewish life, ‘light’ is a grand and welcome theme, particularly at this dark time of year at Chanukah. It is especially so in this pandemic year, and at a time when we are emerging from a socially threatening darkness. Candles, the Chanukiah, stories of the Maccabees, the light that glistens from the pan of frying latkes. Many communities have celebrations involving light. At Diwali in mid-November, Hindus, Jains, and Sikhs celebrate a Festival of Lights, which has its origins in a range of ideas and events; and light fills the household. At Christmas, neighbours decorate their homes and their trees with lights or candles; how beautiful the masses of white and of cobalt blue lights are!

Light, lamps, and candles are important in Jewish life and thought. In the synagogue, the Ner Tamid, the Eternal Light, is a continuously burning lamp suspended from the ceiling above the ark. In Jewish thought, it symbolizes the divine presence in our midst and in the world, and is a tangible reminder of divine power in the creation of the world. The mythological cosmology of Kabbala tells of God’s contracting himself into himself, of withdrawing his own essence from the void thereby creating space in which creation could begin. God then made ten vessels into which to pour light. Three held, but unable to contain the power of that divine light, seven shattered. Tikun Olam is the process of repairing the world by gathering and raising those sparks of light flung out with the shattering. The menorah is another powerful symbol of illumination and of things positive. It ushers in the Sabbath and other holidays. The braided havdalah candle bids farewell to the Sabbath, and illuminates the darkness left by its absence. The yahrzeit candle flickers to remind us of our departed, and to act as a reminder of the light they cast in life. “Yehi or, vayehi or; Let there be light, and there was light”.

Susan Turner is a Winnipeg artist and curator. She designed and, with Stan Carbone, co-curated the 2016 synagogues exhibit at the Jewish Heritage Centre of Western Canada in which the 2015 photos accompanying this article appeared.

Features

What Does The Future of Online Betting Look Like For Canadians?

There have been plenty of positive developments recently in how Canadians can place bets online. A major boost to the Canadian online gambling industry came when Ontario opened its doors to private companies. What further changes lie ahead in the future?

The expansion in Ontario has produced massive revenues for the Canadian gambling industry. Allowing private companies to operate in the province has given gamblers far more choice and they have been flocking to the new sites now available. Great news of course for gamblers and betting companies but also for the taxman. As has been seen in the USA, making gambling legal (especially on sport) has brought in billions of dollars of tax revenue. Canada is now also reaping the benefits and will continue to do so in the future.

The industry was also changed when in 2021 it finally became possible to place single-event bets on sport. Until then it had to be parlays or as they’re also known, accumulators. Both of these changes have seen a great improvement in the online Canadian gambling industry. 2024 has already been a profitable year for the online betting industry in Canada. The first quarter of the 2024-2025 fiscal year certainly illustrated that. The total amount wagered was $18.4 billion and that was 31% higher than the results for the same period in the previous fiscal year.

Revenue in Ontario for the period April 1 to June 30 was $726 million. That’s from the 50 operators who have 80 gaming sites in the province. The total is 34% higher than in the same period in 2023 and 5.2% higher than the previous quarter. With the expansion in Ontario being so successful, the question now is whether other provinces will follow suit. It seems that opening up their gambling industry to private operators may well be the way forward. However, it is recognised that if this is to happen, it must be done safely. Wherever there is legal online betting, it seems that regulation is not too far away. It’s accepted that there is the need for some regulation. Protecting players is vital and with companies required to be licensed, this helps control them. Those who bet at unlicensed sites do not have anywhere near the same level of customer protection and are at risk of online fraud.

There have already been signs of increased regulation of the Canadian online betting industry. How gambling is advertised is always a thorny subject whatever the country. This year has seen the use of celebrities or sports stars in gambling related advertisements prohibited. A key reason for this is to protect youngsters who may be attracted to the industry. Studies have shown that youngsters can identify gambling brands more than they do those for tobacco or alcohol.

It’s also likely that there will be more betting on esports in the future. There has been an increase in the amount of coverage given to them by online betting sites. This was particularly seen during the COVID-19 pandemic when many sports events were canceled. Esports continued and sites such as PowerPlay began to give them increased levels of coverage and will continue to do so.

Technology plays an important role in the gambling industry. Those who love to go online and place bets will see technology producing even more changes in the future.

Banking is an important element of online betting. Improvements in technology in this area have made it far easier to place bets online. Improved encrypting of data and more use of cryptocurrencies also makes it safer when it comes to online financial transactions. Again, this will attract even more gamblers to the industry.

As for the games that are played, particularly when it comes to online casinos, huge strides are taking place. Virtual Reality (VR) and Augmented Reality (AR) are the way ahead, so expect to see more Canadian gamblers wearing VR headsets as time goes by.

The graphics seen in games are already staggering but they will get even better in the future. Putting on your VR headset will see players transported into other worlds and even forwards or backwards in time. Those who love to play at live casinos will be in for a treat. Using their headset, it can appear they are playing at one of the most famous casinos in the world, rather than on their settee.

AI is loved by many but hated by some. It will also have a huge influence on the Canadian online betting industry in the future. This won’t just be in creating games but also be used to deal with customers. AI has the ability to gauge the behavior of gamblers and identify if there is a possible need to help them if spending too much or betting for too long.

Mobile phone technology continues to make advancements. Rather than just playing on your laptop at home, many players download apps and try their luck on their mobile devices. Further advancements are fully expected in the future.

The future of online betting in Canada does look a rosy one. The amount earned by betting companies is expected to increase and that will be good news for those who receive tax revenue. Players will likely have more sites to bet on if other provinces follow in the footsteps of Ontario. The games that will be available will be even more thrilling to play and becoming a member of a site will be safer.

Features

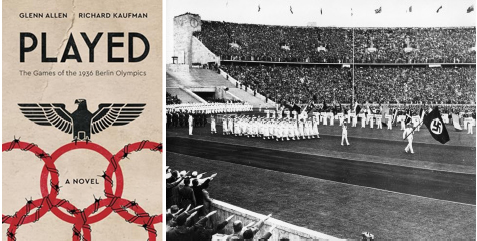

New book chronicles what were arguably the most important – and controversial Olympic Games in history

Review by BERNIE BELLAN With the 33rd Summer Olympics set to take place in Paris from July 26 to August 11, I thought it an opportune time to tell readers about a book that was released earlier this year and which provides a sweeping view of what were arguably the most controversial Olympic Games ever held – the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin, Germany.

Written by two writers, Glenn Allen and Richard Kaufman, who have spent most of their careers writing and producing films, PLAYED: The Games of the 1936 Berlin Olympics combines fiction and non-fiction in a thrilling, yet somewhat confusing manner.

Although Jewish readers are likely to find themselves focused on the rampant antisemitism that pervaded the games – given the determination of Hitler to use the Olympic Games as a masterful propaganda tool, this book is sure to appeal both to fans of the Olympic Games and students of history.

There are many heroes mentioned throughout “PLAYED,” including such well known names as Jesse Owens, who embarrassed Hitler to no end by winning what was then a record four Gold medals in various track events. But there were many other heroes as well, especially Alan Gould, who was the Associated Press Sports Editor, and who wrote many columns calling for a boycott of the games; and William Dodd, the US Ambassador to Germany from 1932-1937, who was warning of the dangers posed by the Nazi threat long before it became all too apparent to politicians, including President Franklin Roosevelt – who adopts quite a sanguine attitude toward the Nazi threat in this book.

And then there are the villains, chief among whom was the despicable Avery Brundage, President of the American Olympic Committee, who was determined to be appointed to the International Olympic Committee (of which he was later to become its president, from 1952-72). It is no coincidence that it was Brundage who was not only the key figure in overcoming resistance to the notion of the US boycotting the 1936 games, it was Brundage who was also central to the 1972 Munich Olympics carrying on even after the massacre of 11 Israeli athletes.

I admit that I knew quite a bit about Brundage’s unsavoury reputation even before reading this book, but the degree to which he connived to make sure America would be represented at the games when there was fierce opposition to exactly that position from many of the leading figures in the sports world in the US at the time is truly shocking.

But, while the historical record provides ample evidence of the extent to which Hitler and his henchmen were determined to use the Olympics as a showcase for Nazi superiority, while reading this book I couldn’t help but wonder just how much fiction was mixed with fact.

In the press release I was sent about the book, it was noted that “Based on real stories and real people involved in the 1936 Berlin Olympics, PLAYED plunges readers into a compelling, fictionalized account of the insanity and hysteria that unfolded across Germany, the United States and in much of the world from 1931 through 1936.”

I couldn’t help myself from questioning: Just how much is fact and how much is fiction in this book? Of course, given that the authors use their imaginations to conjure up the dialogue in the book, I kept thinking to myself – especially as I was reading about how sexually aggressive many of the female characters in this book were: Is this a case of two screenwriters using their past experiences writing movie scripts as an excuse to infuse something that might be passed off as a largely historical account with a great big dollop of licentiousness in order to attract readers?

Two of the major female characters: Martha Dodd, daughter of US Ambassador Dodd, and Eleanor Holm, a champion US swimmer, certainly led carefree sex lives – at least if you were to believe the accounts given in this book. Dodd, in particular, is such a fascinating character, because not only was she quite willing to go to bed with many Nazis (and it seemed – anyone who asked her), including Ernst “Putzi” Hanfstatengel, described as Hitler’s henchman – who would eagerly dispatch anyone Hitler wanted rid of, in time Martha Dodd ended up in the arms of a Russian spy – who himself was ordered executed by Stalin.

As for Holm, even though she was a champion in the swimming pool (in backstroke events), she hardly led a disciplined life as an athlete. In PLAYED, at least, she is one hell of a “player” – and this was well after she was married!

Unfortunately for Holm, however, one man who lusted after her – and whom she detested, was Avery Brundage. Now, I did try to find out whether the account given by Kaufman and Allen of what happened between Holm and Brundage when they were both on the same ship headed to the Berlin Olympics with the entire American team of athletes and officials, was in any way true. (In the book, Brundage attempts to rape Holm, but given her athleticism, she manages to deliver a solid kick to his nether regions – leaving him writhing in pain. The next day, he decides to kick her off the US Olympic team.) According to Holm’s own account, however, the reasons for her being booted off the team had to do with her not wanting to go to bed when she was told to do so. (I much prefer the PLAYED version – and if they ever make a movie from the book, I’m sure audiences would be much more interested in watching Holm do to Avery Brundage what a lot of women would probably fantasize about doing to men.)

Of course, the parts of the book describing some of the leading Nazis, including Hitler himself, along with Joseph Goebbels and Herman Goering, are luridly detailed – as one would expect any description of them to be, but one character who comes off quite favourably – much to my shock, is Leni Riefenstahl, the famed German filmmaker, who had already established a notorious reputation as a propagandist in her famous documentary about the 1934 Nuremburg Rally, “Triump of the Will.”

Rather than painting her as a tool of the Nazis though, the authors offer quite a sympathetic – even admiring portrait of someone who was wedded to her craft. According to this book, Riefenstahl actually fell in love with a member of the US Olympic team by the name of Glenn Morris, who goes on to win Gold in the decathlon competition. (Again, however, there is one unforgettable scene where Morris, after winning his medal, runs over to Riefenstahl, rips off her blouse, and kisses her breast. Is this a Hollywood screenwriter’s fantasy? Who knows?)

There are also many stories of Jewish athletes in this book – some of which are tragic. The female high jump champion in Germany at the time was someone by the name of Gretel Bergmann. Bergmann had gone to England prior to the Olympics knowing full well that she would not be allowed to compete for Nazi Germany. In the book, Putzi goes over to England and threatens Bergmann that she will have to return to compete for Germany, otherwise her family – who had still remained in Germany, will face severe consequences. When Bergmann reluctantly returns to Germany, Brundage points to her becoming part of the German Olympic team as a sign that the Nazis have softened their stance toward Jews, but once the American do agree to participate and cross the ocean to Germany, Bergmann develops a mysterious “injury” that prevents her from actually being part of the German team.

The book is full of such stories – so many, in fact, that your head will be spinning trying to keep track of all the characters mentioned in the book.

Still, if you want to enjoy a rollicking read that may or may not have many parts that are wholly concocted from the writers’ imaginations even though they’re writing about actual events, then you might want to give PLAYED a shot.

As for this year’s version of the Olympics, while there isn’t nearly the same dramatic tension surrounding them as there was prior to and during the 1936 Berlin Olympics, the cheating, skullduggery, and propaganda that permeated the 1936 games has forever tarnished the reputation of the Olympic Games and, while it’s a different type of antisemitism that we’re seeing on the world stage these days, we’re all holding our collective breaths wondering how Israeli athletes are going to be treated in Paris – the same way Jews were wondering how Jewish athletes were going to be treated in Nazi Germany in 1936.

PLAYED: The Games of the 1936 Berlin Olympics

Published 2024 by WordServe Publishing

419 pages

Features

Canada’s favorite online casino games

The people of Canada sure love to play casino games. Gaming and placing bets is a popular pastime in the country with 76 percent reporting that they have participated in at least one form of gambling within the last year. In recent years, the online industry has seen a significant boost as players look to play at the best Canadian online casinos as more provinces look to remove prohibitive legislation.

We take a deep dive into the current legal situation for both online and offline casino gaming in the country, in addition to which casino games are the most popular and what there is to love about them, as well as what the future of the Canada’s online casino landscape could look like.

Both online and offline casino gaming is popular. When playing games online, players look for convenience, security and a good variety in bet and game choices. When going to a land-based gambling venue, they look for a comprehensive entertainment experience, they expect a trip to a casino to be an exciting day out.

The laws in Canada are complex in regards to what types of gambling are legalized and how it is regulated.

The lowdown on gambling laws in Canada – online and offline

Under federal law in Canada, technically the provision of all gambling related services is prohibited. However, exceptions are applied when it is regulated at a local or provincial level.

Each province has the responsibility of regulating and creating laws that concern all types of gambling within them. If they chose to do so then they can provide licenses, manage revenue distribution and set their own age restrictions. Most provinces in Canada have now legalized gambling in some form, with some areas having a more prohibitive approach than others.

For example, Ontario is probably the least restrictive and there are a number of land based casinos venues here open to residents and tourists. Also, there has been a recent introduction of iGaming in the province too.

There are now more provinces looking to follow in Ontario’s footsteps with Alberta looking at taking a less restrictive stance. Currently, charities and religious organizations are allowed to register as gambling providers. There is also an online gambling site based in Alberta that is regulated.

In Canada, the Criminal Code does not actually make specific reference to online gambling activity, which has left it open somewhat to interpretation. The federal government itself has not created any laws specific to online casinos, some provinces are now establishing their own regulations. Also, online casinos and other gambling sites that are operated outside of the country are accessible to people within Canada.

There are a few casino games that are particularly popular in Canada

Slots

From electronic machines to table games, Canadian’s love all types of casino activities. Slots and online slots are one of the top games enjoyed in the country. One reason that people love slots is due to their simplicity, there are no complex rules to get to grips with.

Online games and offline slots are very similar, however online games tend to have more special features and bonus rounds. You might also find that the minimum bet amounts are lower. Slots come in all kinds of themes, from movie themed games to those inspired by ancient Egypt and the pharaohs, there are thousands to choose from online.

Poker

Another well-loved casino game in Canada is poker, a game that has been around for hundreds of years and can also be played online. Poker is a bit more complex and requires patience in order to develop the necessary skills and strategy to be confident when playing the game.

Texas Hold’em is the most common variant of the game in this region, although three card poker, omaha and seven card stud are just some examples of the other types of poker enjoyed here.

Roulette

Roulette is also a top game for Canadian casino enthusiasts. The three main variants are American, European and French, with the American roulette game being the most widely recognized across Canada. Each variation has a slightly different format and house edge as well as different betting options.

Blackjack

Blackjack, also known here as 21, is a top card game. The player is playing against the dealer and to win they must try to get to 21, or as close as possible, before the dealer does.

The future of online casinos in Canada

As casino related legalization across Canada becomes less restrictive and more online operators set up in the region, we can expect this industry to flourish in the years ahead. Player numbers are likely to continue to grow and new technologies like AI will further improve and personalize the experiences users have on gaming sites.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login