Features

Shindico celebrating 50th anniversary this year – the Sandy Shindleman story

By BERNIE BELLAN Anyone who has ever driven through Winnipeg is bound to have noted the very many buildings – including strip malls, shopping centres, office buildings, and apartment buildings, that bear the name “Shindico”.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the founding of Shindico. While its name may be familiar to most Winnipeggers, there’s not a lot that’s been written about how Shindico came to be.

Recently I had the chance to speak with Shindico founder Sandy Shindleman who, now 68, started Shindico when he was only 18.

Anyone who knows Sandy is familiar with his wry wit – and often self-deprecating style. In many ways his story is similar to the stories of many other self-made entrepreneurs within Winnipeg’s Jewish community.

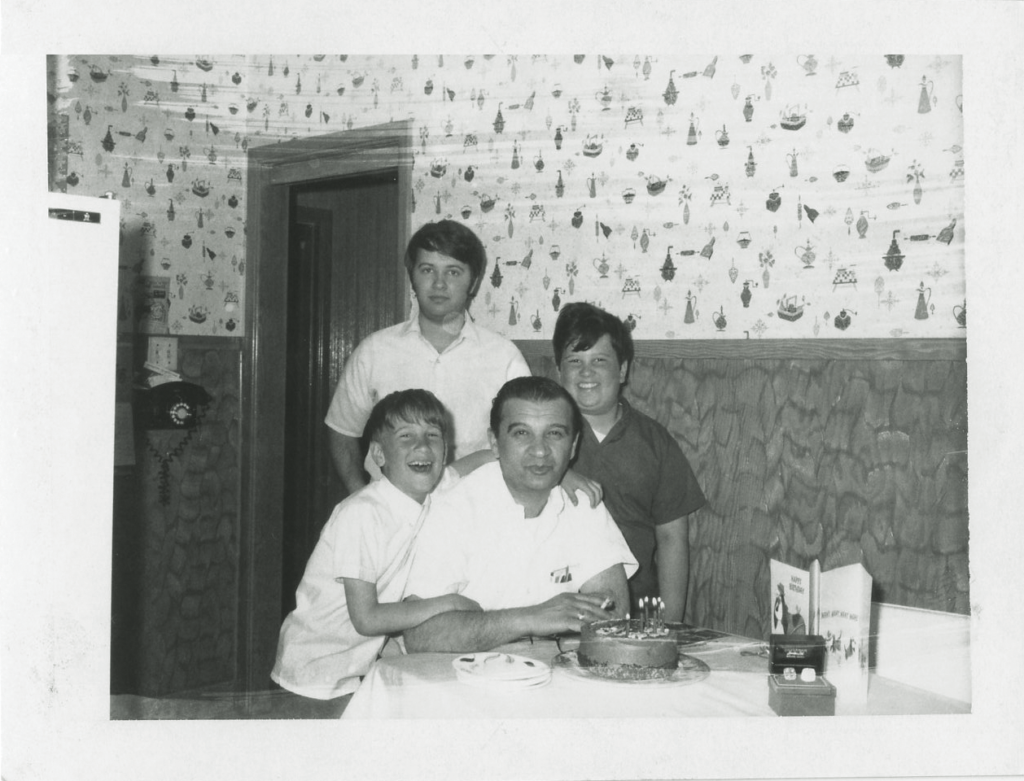

Born in a small town – in this case Portage la Prairie, Sandy was one of three brothers, (the others being Robert and Daniel). The brothers’ parents, Eddie and Claire (née Abells), are both deceased, Eddie having died in 1998, while Claire died in 2019. Eddie’s brother Jack, who worked with Eddie in the grocery store that Eddie owned in Portage (known as Greenberg’s Grocery), passed away in 2020.

Eddie Shindleman’s own father came to Canada in 1912 – from Ukraine (which was then part of Russia, Sandy reminded me.) Claire’s parents were from Belarus. Like many other Jewish immigrants, Sandy’s grandfather went into the cattle business – which Eddie Shindleman remained very much involved in, operating an abattoir (slaughterhouse) in Portage for many years.

Sandy recalls his years growing up in Portage with fondness. There were about “25-35 Jewish families in Portage,” he recalls, many of whom had arrived there after World War II.

The grocery store that his father ran was actually purchased from Eddie Shindleman’s brother-in-law in 1967. Prior to that Eddie had managed the store. As well, Claire and her brother owned a motel in Portage, the “Westgate Inn,” which remained owned by the Shindleman family until this month.

I asked Sandy about the spelling of the name “Shindleman.”

Shouldn’t it be spelled “Shindelman,” I wondered?

His father misspelled it, Sandy said. It should have been “Shindelman,” not “Shindleman.” I asked whether “shindel” meant something in Yiddish. He answered that the family thought it meant “roofer,” but when I checked, the word “shindle” actually means scissors in Yiddish.

While Sandy did work some in the family grocery store, he also had occasion to help his father with the abattoir – which leads to a great story I’d first heard Sandy tell back in 2018, when I had invited him to speak to a group that I had helped start at the Rady JCC (along with Tamar Barr), known as the Jewish Business Network.

The story of the bull and “old man Schweitzer”

When I spoke to Sandy again recently, I invited him to repeat that story because it was both funny – and insightful.

The story goes like this: “I was 14 years old. The store was open till nine o’clock on Friday.” One Friday, on a June evening, after the store had closed Sandy’s father asked Sandy to go out to a farm owned by someone Sandy knew only as “old man Schweitzer.” (He never did find out Schweitzer’s first name, he told me.)

Schweitzer lived on an 80 acreage farm, Sandy continued, but he didn’t grow anything. He didn’t even have any cattle or chickens. All that he had was a bull and he wanted to sell his bull to Eddie Shindleman.

But old man Schweitzer didn’t drive. He didn’t own a truck. All that he owned was a tractor, Sandy said.

“He drove into town and he shopped at my dad’s store on a tractor because you didn’t need a driver’s license to drive a tractor. And as far as I know, you still don’t. But the tractor was open – like it didn’t have a closed cap.”

Now, at the time, Sandy was only 14 years old. Here he was, being asked to drive out to a farm – and pick up a bull. He said that he already knew how to drive a truck (even though he wasn’t legally supposed to be able to do that), so he went to Schweitzer’s farm in a five-ton truck, along with a hired hand who worked in the abattoir.

Eddie had given Sandy a blank cheque to take with him. Eddie had told Sandy to offer Schweitzer a fair price for the bull and not to try and take advantage of him. Sandy said he looked the bull up and down and offered Schweitzer $420 – which Schweitzer accepted.

So, Sandy and the hired hand loaded the bull on to the truck – which was quite a job, since it turned out the bull weighed 1400 pounds.

It was past dark when Sandy got back to Portage. “I drove by the store. My dad came out and climbed up on the truck and looked at the bull. And he said, ‘How much did you pay for it?’ I said ‘$420.’

“And he didn’t say good job, bad job, nothing.”

Now, Sandy had thought that his father wanted the bull for slaughter, since it was June and Eddie was going to need a lot of ground beef tor the upcoming Portage fair. But when Eddie took a look at the size of the bull, he realized it was too big for him to slaughter. “It would have broken the hoist,” Sandy explained.

Instead, Eddie decided to ship the bull to Burns Meats in Winnipeg.

“We had a special relationship with Burns Meats,” Sandy explained. “We provided a lot of their kill on a weekly basis. And so they treated us well. And we always sold things dressed weight. So it didn’t matter if the thing was full of water, it was dressed weight on the rail.”

Another week went by, and Burns Meats had sent a cheque for the bull. It was for $1,000.

Eddie didn’t say anything immediately when he saw how much the cheque was for.

Sandy said though, that later that day, when “there’s a lull in the store at six o’clock – when everyone’s eating dinner…my dad said, ‘What did you think of the bull sale?’ I said, ‘Well, I think I should quit school. I’ll buy a bull or two a week. And I’ll make more than you’re making standing here in the store.’

“ ‘Yeah.’ he said, ‘Could you have bought it for $350?’ I said, ‘Should I have?’

“He said, ‘no.’ He said, ‘What if old man Schweitzer didn’t take your offer and shipped the bull himself?'”

Eddie did some figuring how much it would have cost Schweitzer to ship the bull and came to the conclusion that Schweitzer would have “got about $780, not $420.”

So he told Sandy to go back to Schweitzer’s and write him another cheque for $400.

Sandy said that when he went back to Schweitzer’s, “I didn’t know that old man Schweitzer had hair because I’d never seen him without” the white hard hat he always wore.

But, he said to Schweitzer: ” ‘Mr. Schweitzer, I made a mistake on the bull. I misjudged the weight. And I have a check here for you.’ And I slid the check across his round table.”

Schweitzer though, said that instead of accepting the cheque he wanted to sign it right back over – and use the money instead as credit for groceries in Sandy’s father’s store.

But when Sandy returned to the store with cheque in hand, as he described it: “My dad is in the corner at the store, leaning over looking out the door, and I see he’s tearing up the check that I gave him. And I said, ‘Why are you doing that? He said, ‘Well, let Trudeau pay for half his groceries.’ “

The moral of the story though – and one that Sandy says has stuck with him throughout his business career, was “I realized that we were succeeding. These were customers. We succeeded by helping others succeed.”

Sandy ventures into real estate at age 18

How Sandy Shindleman came to be involved in real estate is another good story. As he tells it, there was a certain real estate salesman in Portage by the name of Danny Maxwell. According to Sandy, Maxwell told him he had to work only a couple of hours a week in order to make what was a pretty good living, so the idea of venturing into becoming a real estate salesperson had great appeal for someone who was still a teenager.

As he says, “it seemed like an easier way to make a living than what we were doing – standing in the store, carrying bags of flour, sacks of potatoes and cutting meats, et cetera – and kind of being stuck in one place. So, it seemed to me that that was something that should be explored.”

Sandy wrote the real estate licensing exam while he was still in high school. The exam was proctored by the Yellowquill junior high school principal (which was, by the way, not the junior high school Sandy attended).

With real estate license in hand, Sandy decided to make the big move to Winnipeg – on his own.

His first sale, he says, came courtesy of Zivey Chudnow, who owned a building in the Inkster Industrial Park (at 11 Plymouth; it’s now an Amazon warehouse) that he wanted to sell.

Sandy explains that he got to know Zivey when Sandy was only five years old and “used to shag golf balls for him” in Clear Lake.

But, that first successful foray into the real estate business did not lead to a whole series of other successes. As Sandy notes, “after that, I couldn’t make another sale because who’s going to buy anything from an 18-year-old farmer who doesn’t know anything about real estate? In commercial real estate, your buyer knows more than you and the seller knows more than you, but to sell a house, you know, what do I know about a house? I lived in a house. That was about the extent of it.”

So, he thought he might have better luck trying to sell farms. After all, he grew up in Portage and knew a lot about farms. That, too, didn’t pan out: “I wasn’t that successful selling farms. I put an ad in the paper to attract buyers and I tried to sell farms,” but without any success.

Instead, he decided to try his luck at buying some properties himself. “I bought some commercial buildings in Winnipeg and Portage – old buildings, you know, two suites upstairs that shared a bathroom and, you know, old grocery stores that were junk. One of them is still standing, 618 Saskatchewan Avenue West. The other ones aren’t. They fell down, I imagine.”

Things started to change for the better though when Sandy (who, by this time was joined by his older brother Robert) saw an empty Co-op store at 1068 Henderson Highway. Next to it, he says, were “a library, car wash, a Dairy Queen, and a gas bar.” The Co-op owned everything, and Sandy decided to make an offer to purchase what is now known as Rossmere Plaza from the Co-op, which was accepted.

Shindico begins a long and successful relationship with the Akman family

The purchase was completed with the Akman family, and the project was managed and run by Shindico (Sandy says the development was originally built by the Simkin family in the 1960s.) For Sandy, making that first major acquisition proved to be the beginning of a long relationship with the Akman family – something that eventually ended with Shindico acquiring Akman Management in 2023 from Danny Akman.

It was not long after that Sandy saw another opportunity when an empty Loblaws store on Pembina Highway was also for sale. As he says, it was around 1982, and the market for retail was “dead… There were a lot of experienced people that did office leasing, industrial, land, and apartments But retail – there was no glamour in that, so it wasn’t crowded.”

I asked how he financed those early acquisitions? Sandy explained that there were a lot of trust companies at the time – almost all of which have disappeared, but they were willing to lend him money. His approach, he noted – and it’s been his approach throughout his business career, he said, is to “work backwards. I find out how much rent something could produce. And then how much would I have to spend to get that rent?

“Do I have to build a building? Do I have to renovate the building and buy the building? And would the rent allow me to borrow most of the money? Then I would know how much I could pay for it.”

In addition to the trust companies, there were a lot of other “small lending institutions” around that time, he said. Lending “was a competitive business” and Shindico was forging a reputation as a prudent manager with a sophisticated leasing platform, attractive to market tenants. Sandy noted, for instance, that in the early years a lot of the properties Shindico developed were formerly gas stations because gas stations were “closing at that time. The lots were too small for the kinds of uses that they (service stations) have now.”

Sandy also pointed out that a lot of the over 180 properties that Shindico has owned in Canada and the United States over the years, have had the same tenants, such as Domino’s Pizza and Macs Milk Stores. Shindico still owns and operates over 160 properties in Canada and the United States, he added.

But, as Shindico grew, it began to branch into other areas of real estate beyond strip malls. Later on in its growth, Shindico also began Big Box development with companies, such as Walmart, Best Buy, Costco, Real Canadian Superstore, Ashley Furniture, Sobeys, and Safeway. Shindico has also been active in the Tenant Representation business, finding suitable spaces for business like Sobeys, Starbucks, Boston Pizza, Popeyes Chicken and several more. Examples include Grant Park Festival and Grant Park Pavilions (on Taylor Avenue), which are continually expanding. Shindico’s most recent success has been to bring Costco to its Westport development in Winnipeg. This is a much needed fourth store in Winnipeg and will serve all of Western Manitoba, and bring an exciting mixed use development to the area.

A key milestone for Shindico was diversifying into the acquisition and management of apartment buildings in 1984 when it purchased: Number One Evergreen Place – where Sandy and his wife Diane lived for a time.

More recently Shindico has developed purpose built apartment buildings, starting with the Taylor Claire on Taylor Avenue (named for the Shindleman brothers’ mother), followed soon thereafter by the Taylor Lee (named after their good friend and contractor, Robbie Lee) just down the street. Sandy says there will be more apartment buildings on Taylor Avenue in the future.

I asked him why Shindico waited so long before it began moving into the building of apartment buildings? He answered that “I didn’t have the money. You need a lot of money. You know, you’re not pre-leasing them. I can’t get you to sign a lease for three years from now.”

Always cautious in his ventures, Sandy said that for years he also had wanted to get into the personal storage business. “I wanted to be in personal storage probably for 25 years,” he said, “but I couldn’t figure out how to get the equity to build one because again, you don’t sign a lease three years in advance for your personal storage. You can’t pre-lease it. You have to learn that business and learn the market before you could” get into it. But Shindico now owns two personal storage locations – one in Transcona and one on Waverley.

Shindico’s many generous contributions to Winnipeg…and Portage

If I had wanted to write a story detailing all the many facets of Shindico’s business, however, this already very long story could have gone on for many more pages – and even though I suppose anyone reading it might seem like it’s really just a promotional piece for Shindico, I would argue that Shindico is one of Winnipeg’s truly great success stories that doesn’t seem to get very much recognition in the media.

Shindico and the Shindleman family are proud supporters of the communities in which they live, work, and play. Through generous donations to the Health Sciences Centre Foundation and investment in the Shindleman Aquatic Centre in Portage la Prairie, the Willow Tunnel at Assiniboine Park & Zoo, The Canadian Museum for Human Rights and Edward Shindleman Park in Winnipeg, they continue to support important initiatives that are close to their hearts and provide access to great spaces for all to enjoy.

Shindico has produced a very slick four-minute video, which can be viewed on YouTube and the Shindico website, that highlights the tremendous growth that the company has undergone in its 50 years of existence, but my interest in writing stories that have a business component is to try and shy away from analyzing financial aspects that might make one business more successful than another. Instead, I’ve always been more interested in individuals’ personal stories – and what made them tick.

Sandy’s trip to Russia in 1991 – when Russia was in total upheaval

Since Sandy Shindleman is such a great story teller (which I first learned when I heard him at that Jewish Business Network meeting eight years ago), when I spoke to him for this story I asked him to repeat a story he had told about a trip he took to Russia back in 1991.

Sandy has often been called upon to give lectures about commercial real estate in a great many different cities, but it was that trip to Russia which might be the most memorable of any of his many trips.

Readers might recall that 1991 was one of the most turbulent years in Russian history. Mikhael Gorbachev, who was Soviet President and General Secretary of the Communist Party at the time, had announced that there were was to be a free election in what was then still the Soviet Union, but chaos was descending upon Russia as old-line Communists were reluctant to cede power and the pro-democracy forces, led by Boris Yeltsin, were anxious to democratize the country.

Sandy had been invited to give a lecture on commercial real estate by someone from within what was by then known as the Russian Federation (although he says he’s not really clear where the invitation came from). He recalls taking a flight from Montreal to Paris, then on to Moscow, where he was joined by two other guys who were also supposed to be giving lectures on real estate.

But, as Sandy describes it, “I landed and the other two men were there. And I didn’t realize that they were both former CIA guys, because they spoke Russian.”

All hell was breaking loose in Moscow at the time, but Sandy says he was totally oblivious to what was happening. “I didn’t know what was going on. There’s no television, there’s no Tom Brokaw explaining to us what’s going on. Bernie Bellan isn’t writing about it. There’s just a bunch of people running around, and we really didn’t know what we were looking at.”

I asked him whether he ended up giving a lecture? Sandy says he did, but “we were supposed to have simultaneous translation, which we didn’t. We had a guy – Vladimir, who was supposed to help,” but Sandy says he doesn’t really know what Vladimir’s role was.

Shindico moves into the construction business

Getting back to the current moment though, given Shindico’s tremendous growth, I wondered what might lie ahead for Sandy Shindleman. He says that the management of the company is in excellent hands, with Alex Akman now Chief Operating Officer, Leanne Fontaine, Chief Financial Officer, and Justin Zarnowski, In-House Legal Counsel.

That brought me back to asking about Shindico’s acquisition of Akman Management in 2023. According to a press release issued at the time, Akman Management portfolio consisted of “1,200,000 square feet of property across 1,000 multifamily units and 18 commercial assets.” The integration of Akman Management resulted in “a 42% increase in staff at the Shindico Group of companies”, and Sandy says “it was great to acquire a like-minded family style company made up of folks that you would want to have lunch with”.

The year 2023 was also an exciting one for Shindico in that it marked the founding of SNR Construction Ltd, a general contracting division in the Shindico Group of Companies. SNR recently completed an 84,000 square foot warehouse for Shindico in the St. Boniface Industrial Park, and is working on a wide array of multi family and retail projects across the Shindico portfolio.

Considering how successful Shindico has been, I wondered whether Sandy ever thought of taking Shindico public and allowing investors to buy stock in it?

Sandy says he’s not interested in going public, saying “we’re a family office, family business – Alex, Justin and Leanne and others. We’ve got a, a kind of a management group of at least a dozen… We’re just a small company…we can have the leverage of running real estate.”

By the way, Sandy’s brother Robert, Executive Vice President of the Shindico Group of Companies, is an important part of the organization, overseeing property development, operations, and management. Sandy’s wife, Diane, is also very involved in the businessm- as Executive Vice President, Finance. Their daughter, Annie, a graduate of Gray Academy, is currently enrolled in the Asper School of Business. “Perhaps, one day, my daughter might join us,” Sandy said, but in the meantime, as he says in the 50th anniversary Shindico video on YouTube, his goal for Shindico “for the next 50 years is supporting and leading all our professional management to grow.”

Features

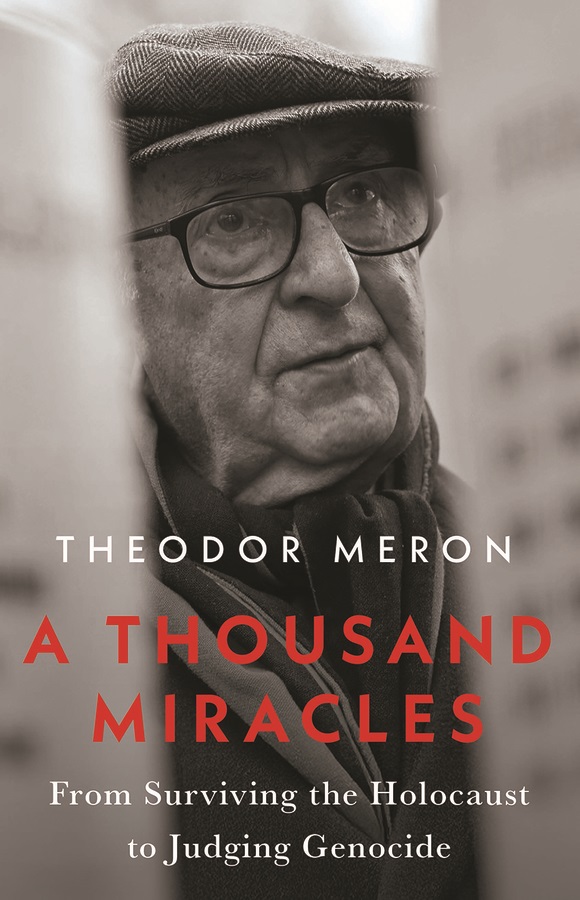

A Thousand Miracles: From Surviving the Holocaust to Judging Genocide

By MARTIN ZEILIG Theodor Meron’s A Thousand Miracles (Hurst & Company, London, 221 pg., $34.00 USD) is an uncommon memoir—one that links the terror of the Holocaust with the painstaking creation of the legal institutions meant to prevent future atrocities.

It is both intimate and historically expansive, tracing Meron’s path from a child in hiding to one of the most influential jurists in modern international law.

The early chapters recount Meron’s survival in Nazi occupied Poland through a series of improbable escapes and acts of kindness—the “miracles” of the title. Rendered with restraint rather than dramatization, these memories form the ethical foundation of his later work.

That moral clarity is evident decades later when, on the seventy-fifth anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, he addressed the UN General Assembly and reminded the world that “the German killing machine did not target Jews only but also the Roma, Poles, Russians and others,” while honoring “the Just—who risked their lives to save Jews.” It is a moment that encapsulates his lifelong insistence on historical accuracy and universal human dignity.

What sets this memoir apart is its second half, which follows Meron’s transformation into a central architect of international humanitarian law. Before entering academia full time, he served in Israel’s diplomatic corps, including a formative posting as ambassador to Canada in the early 1970s. Ottawa under Pierre Trudeau was, as he recalls, “an exciting, vibrant place,” and Meron’s responsibilities extended far beyond traditional diplomacy: representing Israel to the Canadian Jewish community, travelling frequently to Toronto, Montreal, and Vancouver, and even helping to promote sales of Israeli government bonds. His affection for Canada’s cultural life—Montreal’s theatre, Vancouver’s “stunning vistas”—is matched by his candor about the political pressures of the job.

One episode proved decisive.

He was instructed to urge Canadian Jewish leaders to pressure their government to move the embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem—a request he found ethically questionable. His refusal provoked an attempt to recall him, a move that reached the Israeli cabinet. Only the intervention of Finance Minister Pinhas Sapir, who valued Meron’s work, prevented his dismissal. The incident, he writes, left “a fairly bitter taste” and intensified his desire for an academic life—an early sign of the independence that would define his legal career.

That independence is nowhere more evident than in one of the most contentious issues he faced as legal adviser to the Israeli Foreign Ministry: the legal status of Israeli settlements in the occupied West Bank. Meron recounts being asked to provide an opinion on the legality of establishing civilian settlements in territory captured in 1967.

His conclusion was unequivocal: such settlements violated the Fourth Geneva Convention as well as the private property rights of the Arab inhabitants. The government chose a different path, and a wave of settlements followed, complicating prospects for a political solution. Years later, traveling through the West Bank, he was deeply troubled by the sight of Jewish settlers obstructing Palestinian farmers, making it difficult—and at times dangerous—for them to reach their olive groves, even uprooting trees that take decades to grow.

“How could they impose on Arab inhabitants a myriad of restrictions that did not apply to the Jewish settlers?” he asks. “How could Jews, who had suffered extreme persecution through the centuries, show so little compassion for the Arab inhabitants?”

Although he knew his opinion was not the one the government wanted, he believed firmly that legal advisers must “call the law as they see it.” To the government’s credit, he notes, there were no repercussions for his unpopular stance. The opinion, grounded in human rights and humanitarian law, has since become one of his most cited and influential.

Meron’s academic trajectory, detailed in the memoir, is remarkable in its breadth.

His year at the Max Planck Institute in Heidelberg (1984–85) produced Human Rights Law–Making in the United Nations, which won the American Society of International Law’s annual best book prize. He held visiting positions at Harvard Law School, Berkeley, and twice at All Souls College, Oxford.

He was elected to the Council on Foreign Relations in 1992 and, in 1997, to the prestigious Institute of International Law in Strasbourg. In 2003 he delivered the general course at the Hague Academy of International Law, and the following year received the International Bar Association’s Rule of Law Award. These milestones are presented not as selfpromotion but as steps in a lifelong effort to strengthen the legal protections he once lacked as a child.

His reflections on building the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY)—balancing legal rigor with political constraints, and confronting crimes that echoed his own childhood trauma—are among the book’s most compelling passages. He writes with unusual candor about the emotional weight of judging atrocities that, in many ways, mirrored the violence he narrowly escaped as a boy.

Meron’s influence, however, extends far beyond the Balkans.

The memoir revisits his confidential 1967 legal opinion for the U.S. State Department, in which he concluded that Israeli settlements in the territories occupied after the Six Day War violated international humanitarian law—a view consistent with the opinion he delivered to the Israeli government itself. His distress at witnessing settlers obstruct Palestinian farmers and uproot olive trees underscores a recurring theme: the obligation of legal advisers to uphold the law even when politically inconvenient.

The book also highlights his role in shaping the International Criminal Court (ICC). Meron recalls being “happy and excited to be able to help in the construction of the first ever permanent international criminal court” at the 1998 Rome Conference.

His discussion of the ICC’s current work is characteristically balanced: while “most crimes appear to have been committed by the Russians” in Ukraine, he notes that “some crimes may have been committed by the Ukrainians as well,” underscoring the prosecutor’s obligation to investigate all sides.

He also points to the ICC’s arrest warrants for President Putin, for Hamas leaders for crimes committed on October 7, 2023, and for two Israeli cabinet members for crimes in Gaza—examples of the Court’s mandate to pursue accountability impartially, even when doing so is politically fraught.

Throughout, Meron acknowledges the limitations of international justice—the slow pace, the uneven enforcement, the geopolitical pressures—but insists on its necessity. For him, law is not a cureall but a fragile bulwark against the collapse of humanity he witnessed as a child. His reflections remind the reader that international law, however imperfect, remains one of the few tools available to restrain the powerful and protect the vulnerable.

The memoir is also a quiet love story.

Meron’s devotion to his late wife, Monique Jonquet Meron, adds warmth and grounding to a life spent confronting humanity’s darkest chapters. Their partnership provides a counterpoint to the grim subject matter of his professional work and reveals the personal resilience that sustained him.

Written with precision and modesty, A Thousand Miracles avoids selfaggrandizement even as it recounts a career that helped shape the modern architecture of international justice.

The result is a powerful testament to resilience and moral purpose—a reminder that survivors of atrocity can become builders of a more just world.

Martin Zeilig’s Interview with Judge Theodore Meron: Memory, Justice, and the Life He Never Expected

In an email interview with jewishpostandnews.ca , the 95 year-old jurist reflects on survival, legacy, and the moral demands of international law.

Few figures in modern international law have lived a life as improbable—or as influential—as Judge Theodore Meron. Holocaust survivor, scholar, adviser to governments, president of multiple UN war crimes tribunals, Oxford professor, and now a published poet at 95, Meron has spent decades shaping the global pursuit of justice. His new memoir, A Thousand Miracles, captures that extraordinary journey.

He discussed the emotional challenges of writing the book, the principles that guided his career, and the woman whose influence shaped his life.

Meron says the memoir began as an act of love and remembrance, a way to honor the person who anchored his life.

“The critical drive to write A Thousand Miracles was my desire to create a legacy for my wife, Monique, who played such a great role in my life.”

Her presence, he explains, was not only personal but moral—“a compass for living an honorable life… having law and justice as my lodestar, and never cutting corners.”

Reflecting on the past meant confronting memories he had long held at a distance. Writing forced him back into the emotional terrain of childhood loss and wartime survival.

“I found it difficult to write and to think of the loss of my Mother and Brother… my loss of childhood and school… my narrow escapes.”

He describes the “healing power of daydreaming in existential situations,” a coping mechanism that helped him endure the unimaginable. Even so, he approached the writing with restraint, striving “to be cool and unemotional,” despite the weight of the memories.

As he recounts his life, Meron’s story becomes one of continual reinvention—each chapter more improbable than the last.

“A person who did not go to school between the age of 9 and 15… who started an academic career at 48… became a UN war crimes judge at 71… and became a published poet at the age of 95. Are these not miracles?”

The title of his memoir feels almost understated.

His professional life has been driven by a single, urgent mission: preventing future atrocities and protecting the vulnerable.

“I tried to choose to work so that Holocausts and Genocides will not be repeated… that children would not lose their childhoods and education and autonomy.”

Yet he is cleareyed about the limits of the institutions he served. Courts, he says, can only do so much.

“The promise of never again is mainly a duty of States and the international community, not just courts.”

Much of Meron’s legacy lies in shaping the legal frameworks that define modern international criminal law. He helped transform the skeletal principles left by Nuremberg into robust doctrines capable of prosecuting genocide, crimes against humanity, and wartime sexual violence.

“Fleshing out principles… especially on genocide, crimes against humanity and especially rape.”

His work helped ensure that atrocities once dismissed as collateral damage are now recognized as prosecutable crimes.

Even with these advances, Meron remains realistic about the limits of legal institutions.

“Courts tried to do their best, but this is largely the duty of States and their leaders.”

Justice, he suggests, is not only a legal project but a political and moral one—requiring courage from governments, not just judges.

Despite witnessing humanity at its worst, Meron refuses to surrender to despair. His outlook is grounded in history, tempered by experience, and sustained by a stubborn belief in progress.

“Reforms in the law and in human rights have often followed atrocities.”

He acknowledges that progress is uneven—“not linear,” as he puts it—but insists that hope is essential.

“We have ups and downs and a better day will come. We should work for it. Despair will not help.”

Judge Theodore Meron’s life is a testament to resilience, intellect, and moral clarity.

A Thousand Miracles is not simply a memoir of survival—it is a record of a life spent shaping the world’s understanding of justice, guided always by memory, principle, and the belief that even in humanity’s darkest hours, a better future remains possible.

Features

Gamification in Online Casinos: What Do Casino Online DudeSpin Experts Say

Gamification is one of the trends in modern game development. The technology allows players to interact with in-game elements and complete various tasks to earn additional rewards. Sites like casino online DudeSpin are eager to explore new technologies. Canadian players are particularly drawn to gamification for the opportunity to test their skills and have fun. Various development approaches allow for the implementation of much of this functionality already at this stage of development.

Core Elements of Gamification

Gamification is a technology that implements various elements to increase player attention. This mechanic not only attracts new users but also increases the time spent playing. This method rewards the most active players and also uses interactive elements that evoke certain associations and habitual actions.

Gamification elements include:

Achievement systems. Players earn special points and rewards for achieving certain goals. For example, unlocking a new level awards points and free spins on slot machines.

Leaderboards. Competitive rankings increase player attention and encourage active betting. Furthermore, healthy competition between participants improves their overall performance.

Progressive mechanics. Players consistently achieve higher results, which unlock additional privileges. Constant progression creates the effect of maximum engagement and attention to the user’s personality.

Challenges. Special quests and daily missions help players feel needed, and a structured goal system encourages active betting.

Sites like casino online DudeSpin utilize all these components to make players feel part of a unified, evolving system.

Psychological Appeal of Gamification

The key to gamification’s success is that every player wants to feel special and appreciated. A reward system stimulates dopamine, which creates additional rewarding gameplay experiences. This is how sites like casino online DudeSpin retain a loyal audience and build a strong community.

Stable player progress serves as a motivation to continue betting and unlocking new achievements. Furthermore, a certain level on the leaderboard provides an opportunity to showcase your skills and connect with others at your level. Personalized offers enhance the effect of this uniqueness, encouraging more active betting in games. Structured goals and achievements help players manage their time spent active, focusing only on activities that truly benefit them.

Canadian Perspective on Gamified Casino Experiences

Canadian casinos are using gamification techniques for a reason. They’re developing a legal and modern market that appeals to local audiences. Furthermore, operators like casino online DudeSpin operate in compliance with local laws, which fosters trust.

Another reason for gamification’s popularity is the localization of content. All games, prizes, and tournaments are tailored to the local market. A loyal community communicates in a clear language and interacts according to audience preferences.

Many casinos also integrate responsible options to help players manage their deposits and avoid overspending. This structure makes gamification attractive.

Finally, gamification is already a traditional element of gameplay in Canadian casinos, attracting new audiences and increasing loyalty among existing ones.

Technology evolves alongside new opportunities, and operators strive to offer the best benefits to their most active players. This interaction makes gamification a viable solution for gamblers. Leaderboards, achievements, and adaptive features are particularly popular with Canadian users due to their personalization.

Features

Staying Safe Online: How to Verify Phone Numbers and Emails in a Digital World

In today’s connected world, communication happens instantly. Whether through phone calls, text messages, or email, we receive information faster than ever before. While this connectivity brings convenience, it also increases exposure to scams, fraud, and misinformation. Communities that value strong social ties, philanthropy, education, and global connection—such as Jewish communities worldwide—are particularly active online, making digital awareness essential.

One practical way to stay safe is by verifying unknown phone numbers and email addresses before responding. Modern lookup tools now make this process quick and accessible.

Why Phone and Email Verification Matters

The Rise of Digital Fraud

Across North America and beyond, online fraud has become more sophisticated. Scam calls may impersonate:

- Charitable organizations

- Financial institutions

- Government agencies

- Community leaders

- Family members in distress

Similarly, phishing emails often appear legitimate at first glance, using familiar names or logos to gain trust.

Before replying, donating, clicking links, or sharing sensitive information, verification can prevent costly mistakes.

Common Scenarios Where Verification Helps

1. Unknown Calls Requesting Donations

Many people are generous and active in charitable giving. Unfortunately, scammers sometimes exploit this generosity. If you receive a call asking for contributions to a cause, verifying the phone number can help confirm legitimacy.

2. Suspicious Emails About Account Access

Emails claiming urgent action is required—such as password resets or banking alerts—are common phishing tactics. Looking up the sender’s email can reveal whether it is associated with known fraud reports.

3. Online Marketplace Transactions

When buying or selling items online, verifying the contact details of the other party reduces the risk of fraud.

4. Reconnecting with Old Contacts

Sometimes you receive a message from someone claiming to be an old friend, colleague, or distant relative. A quick lookup can confirm whether the contact information aligns with public records.

Introducing ClarityCheck

One of the tools designed to simplify this process is ClarityCheck. The platform allows users to search for information associated with phone numbers and email addresses, helping individuals make informed decisions before responding.

What Makes ClarityCheck Useful?

Quick Searches

Users can enter:

- A phone number

- An email address

The system then aggregates publicly available data and digital signals connected to that contact detail.

Easy-to-Understand Results

Rather than overwhelming users with technical data, the platform presents results in a structured format, making it easier to interpret findings.

Privacy-Conscious Approach

The service focuses on organizing publicly accessible information, helping users assess risk without intrusive methods.

How Phone Number Lookup Works

When a phone number is entered into a lookup service, several types of information may be identified:

| Data Category | Possible Insights |

| Carrier Information | Type of line (mobile, landline, VoIP) |

| Geographic Indicators | Area code origin |

| Spam Reports | Previous complaints or flags |

| Digital Footprint | Public listings linked to the number |

This information can help users determine whether a number is likely legitimate or potentially fraudulent.

For example, a donation request from a number flagged repeatedly for spam activity would be a clear warning sign.

How Email Lookup Enhances Security

Email addresses often reveal patterns that help identify risk.

Key Signals in Email Verification

- Domain age and reputation

- Presence in public databases

- Links to known scam reports

- Associated online profiles

For instance, an email claiming to represent a large institution but using a newly created domain may warrant caution.

Verification adds a layer of confidence before you respond.

Community Safety and Digital Responsibility

Strong communities rely on trust. However, trust must be balanced with vigilance in digital spaces.

Protecting Elders and Vulnerable Individuals

Older adults are often targeted by phone and email scams. Sharing tools and knowledge about verification can significantly reduce risk.

Encouraging family members to:

- Verify unknown callers

- Avoid sharing financial details immediately

- Consult trusted relatives before responding

can prevent emotional and financial harm.

Practical Steps Before Responding to Unknown Contacts

Here is a simple checklist:

- Do not click links immediately.

- Avoid sharing personal information.

- Verify the phone number or email address.

- Contact the organization directly using official channels.

- Report suspicious activity when necessary.

Verification tools like ClarityCheck fit naturally into step three of this process.

Benefits Beyond Fraud Prevention

While safety is the primary goal, phone and email lookup services can also offer other advantages.

Reconnecting with Confidence

In globally connected communities with family members across countries, unexpected messages are common. A lookup can confirm whether a contact aligns with publicly available information before continuing the conversation.

Professional Due Diligence

For professionals—whether in law, business, education, or nonprofit leadership—validating contact information before engaging in partnerships or transactions adds credibility and reduces risk.

Supporting Charitable Integrity

Legitimate charitable organizations depend on trust. When individuals verify contacts, it discourages impersonation scams that damage the reputation of authentic nonprofits.

Digital Awareness in 2026 and Beyond

As artificial intelligence tools become more advanced, scam attempts may look increasingly realistic. Voice cloning, AI-generated emails, and automated phishing campaigns are becoming more common.

Verification tools help counteract these threats by:

- Identifying patterns linked to fraudulent activity

- Aggregating public signals into accessible reports

- Providing clarity before emotional decisions are made

Digital literacy is no longer optional—it is part of responsible community engagement.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is it legal to look up phone numbers and emails?

Yes, when using services that rely on publicly available information and comply with data protection regulations.

Can lookup tools guarantee accuracy?

No tool guarantees 100% accuracy. Results should be used as guidance, combined with personal judgment.

Should verification replace common sense?

Absolutely not. It should complement cautious behavior and independent confirmation.

Final Thoughts

Community strength is built on trust, generosity, and connection. In a digital era, protecting those values requires thoughtful use of technology.

Verifying unknown phone numbers and email addresses before responding is a simple but powerful step. Whether preventing fraud, safeguarding charitable giving, or reconnecting with old contacts, tools like ClarityCheck help individuals move forward with greater confidence.

Digital awareness is not about suspicion—it is about clarity.