Features

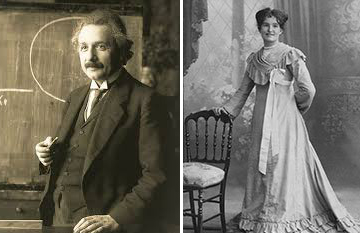

The Dark Side of Albert: Einstein and Marie Winteler, his First Love

By DAVID R. TOPPER As I recall, in the TV series, Genius – which began with a series on Albert Einstein, this one by Ron Howard – the opening sequence showed a middle-aged Albert and his secretary having sex in his office.

I was disappointed, but not surprised. I knew that Albert liked sex and had several partners (in addition to his two wives) over his lifetime. But, for me, it portended the wrong obsession in his life. The true passion throughout Einstein’s life was another “s–word”: namely, science.

But this was TV for a general audience and … well, you can fill in the rest. Plus, what am I being petulant about? After all, here am I, doing the same thing!

We’ll come back to Howard’s portrayal of Einstein’s life at the end; for now I need to put all this in context. For this essay is the second (and last) part of my story of Einstein’s “dark side.”

As shown in the first part, on this website at: The Dark Side of Albert: Einstein and Mileva Marić, his First Wife, which was first published in The Academy of the Heart and Mind, February 7, 2025– Einstein’s loathsome treatment of his first wife often bordered on abuse, or at least very malicious behavior, that diminishes his image as a saintly man; even though many photos of him – especially late in life and with the halo of hair – herald that impression. The other reality, the focus of my first part, was how his maltreatment impacted Mileva and fostered the depression that haunted her all her life. In a sense, and as will be seen here, all this was foreshadowed by Albert’s previous relationship with Marie Winteler, which also had lasting consequences. (As an aside – while I’m in a disagreeable mood about TV portrayals – and since, in part one, I never commented on the TV series: I found Ron Howard’s treatment of Mileva downright offensive. He was obsessed with her orthopedic foot, ever focusing with close-ups of her gait, as she limped into a room. His camera was repeating the shameful behavior of Mileva’s childhood schoolyard chums, who taunted her.)

Now, back to Albert and Marie: we begin with how they met.

In 1895 Albert spent a year enrolled in the cantonal school in the town of Aarau, near Zurich. He had previously taken the rigorous entrance exams for the Polytechnic in Zurich (which Mileva later passed) and had flunked the non-science and non-math parts. But since he did so well with science and math, it was recommended that he do a year of make-up in Aarau; plus, he was applying at age 16, a year early. In Aarau he boarded with the family of Jost Winteler, a teacher at the school (although Albert never took a course from him). Jost and Pauline had three daughters and four sons; the youngest and prettiest daughter was Marie. The family had very progressive social and political views, which Albert admired. They were freethinking, liberal pacifists, and he quickly was comfortable and at ease in this household. Soon he called the parents Papa and Mama.

Marie was two years older than Albert, and was finishing courses toward becoming an elementary school teacher. She was an accomplished pianist, and so she played duets with him on his violin. Albert quickly fell for her, and she for him. We know about this relationship because there are letters exchanged between them when one or the other was out of town, such as Albert visiting his family during a holiday. The relationship eventually was taken seriously by both sets of parents, as seen in a surviving correspondence between the mothers. They gladly anticipated that a marriage was forthcoming. (Incidentally, both mother’s names were Pauline, and so Albert sometimes called them Mama-1 and Mama-2.) While I’m on a tangent here, it will be fitting to mention other connections that later came about. After Albert left Aarau, his sister, Maja, took courses in the city and also boarded with the Winteler family. She fell in love with and married their son, Paul, in 1910. Also Albert’s best friend, Michele Besso, married daughter, Anna, in 1898. In short, these were other ways in which Albert remained linked with the family over his life.

For a glimpse into their relationship, let me quote from letters between Albert and Marie. Listen to the turns of phrase; later I want to contrast this with Albert’s love letters to Mileva. Here are some of his salutations: “My dear little Marie,” “Dearest Sweetheart,” “Sweet Darling,” “Beloved Marie.” Some short phrases: he calls her “my child,” “you delicate little soul,” “you little rascal,” “my comforting angel.” And some sentences. “I love you with all the powers of my beleaguered soul.” “Music has so wonderfully united our souls.” The latter, of course, shows how significant their musical duets were.

Here is a longer piece dated 21 April 1896, where he is replying to a letter from her: “It is so wonderful to be able to press to one’s heart such a bit of paper which [your] two so dear little eyes have lovingly beheld and on which the dainty little hands have charmingly glided back and forth. I was now made to realize to the fullest extent, my little angel, the meaning of homesickness and pining. But love brings much happiness – much more so than pining brings pain. Only now do I realize how indispensable my dear little sunshine has become to my happiness.”

Receiving love letters like this, Marie was smitten by Albert and hence believed that marriage was in the offing. In fact, Albert even corresponded with her mother, saying, for example, “I have thought about you a great deal” and then calling himself her “stepson.” This was in August of 1896, so I’m inclined to believe that he too was thinking of marriage. But inevitably, he was to leave Aarau after passing all his courses, and in October of that year he moved to Zurich to study at the Polytechnic. We know that at the Polytechnic Albert met Mileva, the only woman in his small Physics classes, who was ignored by the other students.

Nonetheless, his correspondence with Marie continued. She was teaching elementary school, writing of her struggles in the classroom, and clearly expecting some talk of marriage. But a hint that something was amiss in their relationship emerges in the opening lines of this letter from Marie, written sometime in November of 1896. To put this into context, you need to know that Albert was sending her his dirty laundry, which she would wash and send back. (Believe me: I’m not making this up.) It goes to show how domestic the relationship was, which reinforces for me Marie’s continued belief in a forthcoming wedding.

She writes: “Beloved sweetheart! Your little basket arrived today and in vain did I strain my eyes looking for a little note, even though the mere sight of your dear handwriting in the address was enough to make me happy.” Nothing but the dirty laundry! Was Albert just taking Marie for granted? We need to keep this in context. We don’t know the extent of his relationship with Mileva this early in the school term. Maybe he still was thinking of marrying Marie. So, at the least it was insensitive. What we do know is that Marie made it clear that this laundry business was no small task; for, later in the letter, she writes. “Last Sunday I was crossing the woods in pouring rain to take your little basket to the post office, did it arrive soon?”

In the same letter she also makes reference to a previous letter from Albert. “My love, I do not quite understand a passage in your letter. You write that you do not want to correspond with me any longer, but why not, sweetheart?” Yes, why not? Perhaps he was involved in some way with Mileva by now and was distancing himself from Marie. She ends the letter with: “I love you for all eternity, sweetheart, and may God preserve and protect you. With deepest love yours, Little Marie.”

Albert wrote to her again. We know this from a letter to him of November 30, 1896 where Marie mentions that she had sent him a gift of a teapot. Apparently he wrote back, calling it “stupid,” which would be downright nasty – but not surprising, since we know how erratic Albert can be. At least, that’s how I interpret this sentence: “My dear sweetheart, the ‘matter’ of my sending you the stupid little teapot does not have to please you as long as you are going to brew some good tea in it.” Quite clearly, Marie doesn’t have it in her to reprimand him for his sometimes nasty behavior.

Later in her letter, Marie talks of her teaching duties, and how much she enjoys the task. Interestingly, she tells him of a “little boy in the first grade who shares with you a facial feature and, imagine that, whose name is also Albert.” She goes on to say how she gives this boy extra help.

Then there is this letter from Albert in March 1897. “Beloved little Marie, I love you with all the powers of my beleaguered soul. … To see you saddened because of me is the greatest pain to me. … How inhuman I must have become for my darling to perceive it as coldness. … What am I to you, what can I offer you! I’m nothing but a schoolboy & have nothing. … And yet you ask whether I love you so much out of pity! … Alas, you so misunderstand the empathy of ideal love.” Remember that phrase “ideal love”; we’ll come back to it at the end.

This brings me to an important letter from Albert to Pauline Winteler, sometime later in 1897, perhaps May. “I am writing you … in order to cut short an inner struggle whose outcome is, in fact, already settled in my mind.” He goes on to speak of the pain he has caused “the dear child through my fault. It fills me with a peculiar kind of satisfaction that now I myself have to taste some of the pain that I brought upon the dear girl through my thoughtlessness and ignorance of her delicate nature. Strenuous intellectual work and looking at God’s Nature are the reconciling, fortifying, yet relentlessly strict angels that shall lead me through all of life’s troubles. If only I were able to give some of this to the good child! … I appear to myself as an ostrich who buries his head in the desert sand so as not to perceive the danger. … But why denigrate oneself, others take care of that when necessary, therefore let’s stop.”

Unmistakably, we know now that, in Albert’s mind, the relationship with Marie is over and he is making a Mea Culpa – of sorts – to her mother. He is repeating what he wrote to Marie, that he is in pain because he has caused her pain – a rather egocentric idea, to say the least. And his excuse? He was too busy with his physics – probing into the mechanism of God’s creation – to deal with the triviality of human interaction. Of course, all this indeed is true, since this is Einstein. But at this stage of his life, it’s really only a young student’s fantasy. More importantly, it exposes what I’ve said above: science was the overriding infatuation in his life. And, God forbid, if someone would try to get in his way.

Indeed, let me repeat this phrase: “if only I were able to give some of this to [Marie].” I read this in light of the fact that in Zurich, Mileva was a fellow student, who knows the physics. It’s now a year into their studies and we know that they were at some stage of a relationship. So, indeed, Mileva could do what Marie could not; namely, converse with Albert about his beloved physics.

This brings me to the first item that proves that Albert and Mileva were in a relationship. It is a letter from Mileva to Albert in 1897, sometime in late October. She is in Germany taking physics courses. The language is formal; like intellectual friends exchanging ideas and experiences. Interestingly, it begins by her thanking him for a four-page-letter to her – which, sadly, we don’t have. But, importantly, she refers to “the joy you provided me through our trip together.” So we know that by now they are a couple. In fact, she mentions that her father gave her some tobacco to give to Albert; so, clearly their relationship is also known to her parents.

It’s also obvious how Mileva has filled in the hole left by Marie’s departure from Albert’s world. Listen to this musing from Mileva. “Man is very capable of imagining infinite happiness, and he should be able to grasp the infinity of space. I think that should be much easier.” Right up Albert’s alley, one might say. And this: “Oh, it was really neat at the lecture … yesterday … on the kinetic theory of heat of gases … [where the professor calculated that the colliding molecules] travel a distance of only 1/100 of a hairbreadth.” Surely, Marie wouldn’t have found this to be “neat” – no, not at all.

Despite Albert and Mileva now being a couple, he was still communicating with the Winteler family, possibly since his sister, Maja, was living with them. Thus, during a visit to his sister, we have this letter from him dated Aarau, 6 September 1899. At the time Marie was no longer living at home. “Dear little Marie, Little Mama relayed to me the friendly greeting that you sent me & the permission to write you. … Until now, the fear of upsetting your delicate heart has always kept me from doing so. … I know, dear girl, what pain I have caused you, and have already experienced grave suffering myself as a result.” Notice how Albert always turns the argument around, excusing himself. It’s like saying: “Oh, I hit you so hard, now my hand hurts. Pity me too.” Pathetic, I say.

He continues: “But if you look forward innocently to communicating with me & are able to replace old unfounded pain with new joy, write to me again.” His phrase “unfounded pain” tells it all. For Marie, the shabby way he treated her, and just dumped her, was real and hurtful. Calling it “unfounded” is an insult. Nonetheless, like Mileva, Marie remained love-struck by the charm of Albert and was ever eager to forgive him.

The story of Albert’s subsequent abusive relationship with Mileva was told in the first Part of the “dark side” of Albert. For now, we need to recall a few milestones in this story, since there is more to tell of Marie – as we follow her through the rest of her life, despite the meagre information we have about this.

Early in 1902 Mileva gave birth to Lieserl, whom she had to give up, after raising her with her Serbian parents for several months. As seen, Albert never saw his only daughter, and Mileva never forgot her. As I argued in part one: giving up Lieserl was probably a major source of the episodically occurring depression throughout her life. In January 1903, Albert and Mileva were married in a small civil ceremony. Neither set of parents attended. Their married life initially went smoothly, settling in Bern, where Albert got a job in the patent office. In his spare time, he was writing landmark papers on physics, while Mileva was the dutiful housewife. Two sons, Hans Albert (1904) and Eduard (1910), were born.

At this point, I sadly need to interject that back in Aarau in 1906, in the Winteler household, their son, Julius – after returning from a trip to America as a cook on a merchant ship – shot and killed his mother along with his sister Rosa’s husband, then himself. I believe this is important for, among other things, the impact it surely had on Marie; although, as far as I know, we have no documented record of this. But we do have the letter that Albert wrote to Jost. Referring to him as “Highly esteemed Professor Winteler,” he offers his “deepest condolences” despite knowing how “feeble words are in the face of such pain.” He also talks of the “kindness” that Pauline bestowed upon him, “while I caused her only sorrow and pain”– clearly referring to his relationship with Marie.

Meanwhile, by around 1909, Einstein was being seen as an important physicist within the European Physics community. In a letter to a close friend, Mileva says that Albert “lives only for his work” and the family is “unimportant to him.” That there was a strain on the marriage is further seen in the fact that Albert sends a letter to “Dearest Marie,” seemingly, of all things, to rekindle their relationship. He tells her that his “life is as wretched as possible regarding the personal aspect. I escape the eternal longing for you only through strenuous work & rumination. My only happiness would be to see you again.”

We don’t have Marie’s immediate reaction to this from Albert, but we can surmise that it would have been quite a shock – or what my late therapist wife would call, using her vernacular, “for crazy making.” Apparently Marie did reply to this letter of September 1909, because we have another letter from Albert in March 1910 in which he speaks of her having “trusted” him last year, but that she regrets it now; and he refers to a meeting between them, naming specific places where they walked in and around Bern. (Marie, at this time, had a teaching job not far from Bern.) And he reiterates: “I think of you with heartfelt love every free minute and am as unhappy as one can be.” Apparently she never replied to this letter, for we have this postcard from him to her on 15 July 1910: “Warm regards to the eternally silent one from your A. E.”

But she did reply to this; we have a letter of 7 August 1910 to her from Albert that begins: “As I was reading your letter, …” However, the message was not what Albert was waiting for, since he continues thusly, “it seemed to me as if I were watching my grave being dug.” I am quite sure I know what is happening here: Marie became engaged around this time, which eventually led to a marriage. So she has obviously told Albert of this, and this letter is his response. He thus goes on: “The little leftover joy that I still had has been destroyed. … However, I thank you … for giving me … the few hours of pure joy … 15 years ago [1895] and last year. Now you are a different person. … Farewell … and think of me [as] the unhappy one, rather than … with hatred and bitterness. … Your, Albert.” Knowing how Marie, like Mileva, was ever-forgiving, she probably harboured no animosity.

On 16 November 1911, Marie married Albert [!] Müller, a watch factory manager, 10 years younger that her. (So, again, another “Albert” has come into her life.) At the time, the Einsteins were in Prague, where Albert accepted an appointment in the German University. Besso told him of the marriage. In his reply, 26 December 1911, Albert writes: “I am sincerely pleased about Marie’s getting married. Thus wanes a dark stain in my life. Now everything is as it should be. Whom is she marrying?” (Incidentally, while mentioning Besso, it’s worthwhile to point out that there is an extensive correspondence between them that continued until Besso died in 1955, just a month before Einstein. For me, one of the riveting highlights of their relationship is the clear resentment of Albert by Besso’s wife, who openly reprimands Einstein for the dreadful way he treated her sister, as well as Mileva – and Anna harps on this, over and over, until she dies in 1944.)

Sometime around the spring of 1912, Besso informs Albert that Marie is pregnant. We know this because in a long letter to Besso of 26 March, near the end, Albert says, “I am happy that you are doing so well, and also that Marie is expecting a little boy (?), to whom I will be a kind of uncle, as a matter of fact.” The reference here is due to the fact that his sister Maja was married to Marie’s brother, Paul. On 8 August 1912 Marie gave birth to a son, they named Paul Albert. She later had a second boy, but I don’t have any further information on this.

While on this topic around Albert and Marie, let me add this. Albert also continued in contact with Marie’s sister Rosa. In a letter to her in January of 1914 he ends it this way (note the sly reference to Marie’s husband, also Albert): “With kindest regards to you and the kids, to Marie and to my namesake and general representative Albert, whose acquaintance I still hope to make one of these days.” As far as I know, Einstein never met Marie’s husband, nor saw Marie ever again.

Her subsequent life, it seems, was not a happy one – although we only have an outline of it, unlike the detailed agonizing life of Mileva that we saw in Part one. Marie and her Albert were divorced in 1927. As seen, she was an elementary school teacher, although records show that she missed a lot of classes due to sickness. She gave piano and organ lessons, possibly to supplement her income; she may have been dismissed from jobs later in life.

We also know that she tried to reach the first Albert in 1940; there exist two letters in June and September to him in Princeton, N.J. (Albert and his second wife, Elsa Löwenthal, had moved to the USA in 1933.) Similar to Mileva pleading for help to get their son Eduard out of Nazi-surrounded Switzerland, Marie wants to immigrate with a son to the USA and is asking for money and help. However, there is no record of him having read these letters. Most probably, his secretary, Helen Dukas – who was known to censor his mail – never showed it to him. But she did save it, along with the rest of the many items she sorted in his daily mailbox.

Marie was often plagued with depression, and in the end she died in a mental institution on 24 September, 1957, over two years after Einstein died. She was 80 years old, having been born on 24 April, 1877.

I will end this story where I began – the TV series by Ron Howard. Not surpassingly, in the episode involving Albert and Marie, he portrays them having an intimate relationship, which I’m quite sure never happened.

My aim here is not about moral values or judgements, but historical accuracy. Somewhere into the third or fourth episodes of Howard’s “Einstein,” I gave up keeping a list of the historical errors – and just sat back and watched it. Nonetheless, it perturbs me how the popular media often play fast and loose with the facts of history. I could harp on and on about how much work and effort goes into the writing of serious history by serious historians – but I’ll leave it there.

Albert and Marie met in the late 19th century, not the late 20th. They were living in a house with two parents and usually six siblings. There was little to no space available for privacy. Recall the salutations of Albert to Marie, and compare them with the following to Mileva: “sweet little witch,” “wild little rascal,” “my little beast,” “my street urchin,” “you wild witch,” “my little brat.” Of course, we know that their relationship eventually was intimate.

To me, the evidence of history suggests that the relationship between Albert and Marie was Platonic. Recall the quote above by Albert about “ideal love” in 1897. Sometime later in her life, Marie succinctly summarized her friendship with Einstein this way:

“Wir haben uns innig geliebt, aber es war eine durchaus ideale Liebe.”

“We loved each other deeply, but it was a completely ideal love.”

* * *

Readings:

The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, Vol. 1-16 (1879-1927), by multiple editors (Princeton University Press, 1987–2021), a work in progress.

The Life and Letters of Mileva Marić, Einstein’s First Wife, edited by Milan Popovic (The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003).

A Solitary Smile: A Novel on Einstein, by David R. Topper(Bee Line Press, 2019).

#

David R. Topper writes in Winnipeg, Canada. His work has appeared in Mono, Poetic Sun, Discretionary Love, Poetry Pacific,Academy of theHeart & Mind, Altered Reality Mag., and elsewhere. His poem Seascape with Gulls: My Father’s Last Painting won first prize in the annual poetry contest of CommuterLit Mag. May 12, 2025

Features

Susan Silverman: diversification personified

By GERRY POSNER I recently had the good fortune to meet, by accident, a woman I knew from my past, that is my ancient past. Her name is Susan Silverman. Reconnecting with her was a real treat. The treat became even better when I was able to learn about her life story.

From the south end of Winnipeg beginning on Ash Street and later to 616 Waverley Street – I can still picture the house in my mind – and then onward and upwards, Susan has had quite a life. The middle daughter (sisters Adrienne and Jo-Anne) of Bernie Silverman and Celia (Goldstein), Susan was a student at River Heights, Montrose and then Kelvin High School. She had the good fortune to be exposed to music early in her life as her father was (aside from being a well known businessman) – an accomplished jazz pianist. He often hosted jam sessions with talented Black musicians. As well, Susan could relate to the visual arts as her mother became a sculptor and later, a painter.

When Susan was seven, she (and a class of 20 others), did three grades in two years. The result was that that she entered the University of Manitoba at the tender age of 16 – something that could not happen today. What she gained the most, as she looks back on those years, were the connections she made and friendships formed, many of which survive and thrive to this day. She was a part of the era of fraternity formals, guys in tuxedos and gals in fancy “ cocktail dresses,” adorned with bouffant hair-dos and wrist corsages.

Upon graduation, Susan’s wanderlust took her to London, England. That move ignited in her a love of travel – which remains to this day. But that first foray into international travel lasted a short time and soon she was back in Winnipeg working for the Children’s Aid Society. That job allowed her to save some money and soon she was off to Montreal. It was there, along with her roommate, the former Diane Unrode, that she enjoyed a busy social life and a place for her to take up skiing. She had the good fortune of landing a significant job as an executive with an international chemical company that allowed her to travel the world as in Japan, Hong Kong, New Zealand, Australia, Mexico, the Netherlands and even the USA. Not a bad gig.

In 1983, her company relocated to Toronto. She ended up working for companies in the forest products industry as well the construction technology industry. After a long stint in the corporate world, Susan began her own company called “The Resourceful Group,” providing human resource and management consulting services to smaller enterprises. Along the way, she served on a variety of boards of directors for both profit and non-profit sectors.

Even with all that, Susan was really just beginning. Upon her retirement in 2006, she began a life of volunteering. That role included many areas, from mentoring new Canadians in English conversation through JIAS (Jewish Immigrant Aid Services) to visiting patients at a Toronto rehabilitation hospital, to conducting minyan and shiva services. Few people volunteer in such diverse ways. She is even a frequent contributor to the National Post Letters section, usually with respect to the defence of Israel

and Jewish causes.

The stars aligned on New Year’s Eve, 1986, when she met her soon to be husband, Murray Leiter, an ex- Montrealer. Now married for 36 plus years, they have been blessed with a love of travel and adventure. In the early 1990s they moved to Oakville and joined the Temple Shaarei Beth -El Congregation. They soon were involved in synagogue life, making life long friends there. Susan and Murray joined the choir, then Susan took the next step and became a Bat Mitzvah. Too bad there is no recording of that moment. Later, when they returned to Toronto, they joined Temple Emanu-el and soon sang in that choir as well.

What has inspired both Susan and Murray to this day is the concept of Tikkun Olam. Serving as faith visitors at North York General Hospital and St. John’s Rehab respectively is just one of the many volunteer activities that has enriched both of their lives and indeed the lives of the people they have assisted and continue to assist.

Another integral aspect of Susan’s life has been her annual returns to Winnipeg. She makes certain to visit her parents, grandparents, and other family members at the Shaarey Zedek Cemetery. She also gets to spend time with her cousins, Hilllaine and Richard Kroft and friends, Michie end Billy Silverberg, Roz and Mickey Rosenberg, as well as her former brother-in-law Hy Dashevsky and his wife Esther. She says about her time with her friends: “how lucky we are to experience the extraordinary Winnipeg hospitality.”

Her Winnipeg time always includes requisite stops at the Pancake House, Tre Visi Cafe and Assiniboine Park. Even 60 plus years away from the “‘peg,” Susan feels privileged to have grown up in such a vibrant Jewish community. The city will always have a special place in her heart. Moreover, she seems to have made a Winnipegger out of her husband. That would be a new definition of Grow Winnipeg.

Features

Beneath the Prairie Calm: Manitoba’s Growing Vulnerability to Influence Networks

By MARTIN ZEILIG After reading Who’s Behind the Hard Right in Canada? A Reference Guide to Canada’s Disinformation Network — a report published by the Canadian AntiHate Network that maps the organizations, influencers, and funding pipelines driving coordinated right wing disinformation across the country — I’m left with a blunt conclusion: Canada is losing control of its political story, and Manitoba is far more exposed than we like to admit.

We often imagine ourselves as observers of political upheaval elsewhere — the U.S., Europe, even Alberta.

But the document lays out a sprawling, coordinated ecosystem of think tanks, influencers, strategists, and international organizations that is already shaping political attitudes across the Prairies. Manitoba is not an exception. In many ways, we’re a prime target.

The report describes a pipeline of influence that begins with global organizations like the International Democracy Union and the Atlas Network. These groups are not fringe. They are well funded, deeply connected, and explicitly designed to shape political outcomes across borders. Their Canadian partners translate global ideological projects into local messaging, policy proposals, and campaign strategies.

But the most concerning part isn’t the international influence — it’s the domestic machinery built to amplify it.

The Canada Strong and Free Network acts as a central hub linking donors, strategists, and political operatives. Around it sits a constellation of digital media outlets and influencer accounts that specialize in outrage driven content. They take think tank talking points, strip out nuance, and convert them into viral narratives designed to provoke anger rather than understanding.

CAHN’s analysis reinforces this point. The report describes Canada’s far right ecosystem as “coordinated and emboldened,” with actors who deliberately craft emotionally charged narratives meant to overwhelm rather than inform. They operate what the report characterizes as an “outrage feedback loop,” where sensational claims spread faster than journalists or researchers can contextualize them. The goal is not persuasion through evidence, but domination through repetition.

This is not healthy democratic debate.

It is a parallel information system engineered to overwhelm journalism, distort public perception, and create the illusion of widespread grassroots demand. And because these groups operate outside formal political structures, they face far fewer transparency requirements. Manitobans have no clear way of knowing who funds them, who directs them, or what their longterm objectives are.

If this feels abstract, look closer to home.

Manitoba has become fertile ground for these networks. Our province has a long history of political moderation, but also deep economic anxieties — especially in rural communities, resource dependent regions, and areas hit hard by demographic change. These are precisely the conditions that make disinformation ecosystems effective.

When people feel unheard, the loudest voices win.

We saw hints of this during the pandemic, when convoy aligned groups found strong support in parts of Manitoba. We see it now in the rise of local influencers who echo national talking points almost in real time. And we see it in the growing hostility toward institutions — from public health to the CBC — that once formed the backbone of civic trust in this province.

CAHN’s research also shows how quickly these networks can grow. Some nationalist groups have seen membership spikes of more than 60 percent in short periods, driven by targeted digital campaigns that exploit economic uncertainty and cultural anxiety. These surges are not organic. They are engineered.

The document also highlights the rise of explicitly exclusionary nationalist groups promoting ideas like “remigration,” a euphemism for mass deportation of nonEuropean immigrants. These groups remain small, but Manitoba’s demographic reality — a province where immigration is essential to economic survival — makes their presence especially dangerous. When extremist ideas begin to circulate within mainstream political networks, they gain a legitimacy they have not earned.

Even more troubling is how these ideas migrate.

CAHN warns that concepts once confined to fringe spaces are now being repackaged in sanitized language and pushed through influencers, think tanks, and political operatives seeking legitimacy. When these narratives appear alongside conventional policy debates, they gain a veneer of normalcy that obscures their origins.

None of this means Manitoba is on the brink of political collapse.

Our institutions remain resilient, and our political culture is still fundamentally moderate. But sovereignty is not just about borders or military power. It is also about information — who controls it, who manipulates it, and who benefits from its distortion. When opaque networks shape public opinion through coordinated disinformation, that sovereignty erodes.

CAHN’s broader warning is that trust itself is under attack. Farright networks intentionally target public institutions — media, universities, public health agencies, cultural organizations — because weakening trust creates a vacuum they can fill with their own narratives. A democracy becomes vulnerable when people no longer share a common set of facts.

The danger is not that Manitoba will suddenly adopt the politics of another country. The danger is that we will drift into a political environment shaped by forces we don’t see, don’t understand, and cannot hold accountable. A democracy cannot function if its information ecosystem is captured by actors who thrive on outrage, opacity, and division.

The solution is not censorship. It is transparency. It is rebuilding trust in journalism. It is demanding higher standards from the organizations that shape our political discourse. Manitobans deserve to know who is influencing their democracy and why.

We are not immune.

And believing we are immune is the most dangerous illusion of all.

Features

Israel Has Always Been Treated Differently

By HENRY SREBRNIK We think of the period between 1948 and 1967 as one where Israel was largely accepted by the international community and world opinion, in large part due to revulsion over the Nazi Holocaust. Whereas the Arabs in the former British Mandate of Palestine were, we are told, largely forgotten.

But that’s actually not true. Israel declared its independence on May 14,1948 and fought for its survival in a war lasting almost a year into 1949. A consequence was the expulsion and/or flight of most of the Arab population. In the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, millions of other people across the world were also driven from their homes, and boundaries were redrawn in Europe and Asia that benefited the victorious states, to the detriment of the defeated countries. That is indeed forgotten.

Israel was not admitted to the United Nations until May 11, 1949. Admission was contingent on Israel accepting and fulfilling the obligations of the UN Charter, including elements from previous resolutions like the November 29, 1947 General Assembly Resolution 181, the Partition Plan to create Arab and Jewish states in Palestine. This became a dead letter after Israel’s War of Independence. The victorious Jewish state gained more territory, while an Arab state never emerged. Those parts of Palestine that remained outside Israel ended up with Egypt (Gaza) and Jordan (the Old City of Jerusalem and the West Bank). They were occupied by Israel in 1967, after another defensive war against Arab states.

And even at that, we should recall, UN support for the 1947 partition plan came from a body at that time dominated by Western Europe and Latin American states, along with a Communist bloc temporarily in favour of a Jewish entity, at a time when colonial powers were in charge of much of Asia and Africa. Today, such a plan would have had zero chance of adoption.

After all, on November 10, 1975, the General Assembly, by a vote of 72 in favour, 35 against, with 32 abstentions, passed Resolution 3379, which declared Zionism “a form of racism.” Resolution 3379 officially condemned the national ideology of the Jewish state. Though it was rescinded on December 16, 1991, most of the governments and populations in these countries continue to support that view.

As for the Palestinian Arabs, were they forgotten before 1967? Not at all. The United Nations General Assembly adopted resolution 194 on December 11, 1948, stating that “refugees wishing to return to their homes and live at peace with their neighbours should be permitted to do so at the earliest practicable date, and that compensation should be paid for the property of those choosing not to return and for loss of or damage to property which, under principles of international law or equity, should be made good by the Governments or authorities responsible.” This is the so-called right of return demanded by Israel’s enemies.

As well, the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) was established Dec. 8, 1949. UNRWA’s mandate encompasses Palestinians who fled or were expelled during the 1948 war and subsequent conflicts, as well as their descendants, including legally adopted children. More than 5.6 million Palestinians are registered with UNRWA as refugees. It is the only UN agency dealing with a specific group of refugees. The millions of all other displaced peoples from all other wars come under the auspices of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Yet UNRWA has more staff than the UNHRC.

But the difference goes beyond the anomaly of two structures and two bureaucracies. In fact, they have two strikingly different mandates. UNHCR seeks to resettle refugees; UNRWA does not. When, in 1951, John Blanford, UNRWA’s then-director, proposed resettling up to 250,000 refugees in nearby Arab countries, those countries reacted with rage and refused, leading to his departure. The message got through. No UN official since has pushed for resettlement.

Moreover, the UNRWA and UNHCR definitions of a refugee differ markedly. Whereas the UNHCR services only those who’ve actually fled their homelands, the UNRWA definition covers “the descendants of persons who became refugees in 1948,” without any generational limitations.

Israel is the only country that’s the continuous target of three standing UN bodies established and staffed solely for the purpose of advancing the Palestinian cause and bashing Israel — the Committee on the Exercise of the Inalienable Rights of the Palestinian People; the Special Committee to Investigate Israeli Practices Affecting the Human Rights of the Palestinian People; and the Division for Palestinian Rights in the UN’s Department of Political Affairs.

Israel is also the only state whose capital city, Jerusalem, with which the Jewish people have been umbilically linked for more than 3,000 years, is not recognized by almost all other countries.

So from its very inception until today, Israel has been treated differently than all other states, even those, such as the Democratic Republic of Congo, Somalia, and Sudan, immersed in brutal civil wars from their very inception. Newscasts, when reporting about the West Bank, use the term Occupied Palestinian Territories, though there are countless such areas elsewhere on the globe.

Even though Israel left Gaza in September 2005 and is no longer in occupation of the strip (leading to its takeover by Hamas, as we know), this has been contested by the UN, which though not declaring Gaza “occupied” under the legal definition, has referred to Gaza under the nomenclature of “Occupied Palestinian Territories.” It seems Israel, no matter what it does, can’t win. For much of the world, it is seen as an “outlaw” state.

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.