Features

The Ethical Yardstick of History: Remembering Irving Abella

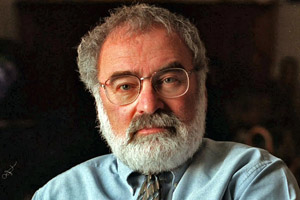

By JAMIE MICHAELS Irving Abella passed away on July 3. He was a special historian. Calling him an optimist might be considered paradoxical given the subjects he researched: the history of Canadian anti-Semitism, the role of racial prejudice in shaping Canadian immigration policy, and Canadian labour history.

Despite the seriousness of his work, Abella was an idealist who believed that we could learn from the mistakes of history to build a better, more humane present. His work has been, and continues to be, formative for young academics—myself included—who strive to leverage history in the pursuit of a kinder world.

Abella was perhaps best known for his 1982 book, “None is Too Many: Canada and the Jews of Europe 1933-1948,” co-written with Harold Troper. The book was awarded the National Jewish Book Award for bringing Canada’s atrocious immigration record into the public spotlight. During the Holocaust, Canada accepted the fewest number of Jewish refugees fleeing Nazism of any refugee accepting nation. In 1939, when an immigration agent was asked how many Jews would be admitted to Canada after the war, he replied, “none is too many.” Abella and Troper’s work introduced the term “none is too many” into the public consciousness. This abysmal policy failure became, in Abella’s words, “an ethical yardstick against which contemporaneous government policies are gauged.”

As this previously unknown history was brought to light Canada was forced to re-examine its immigration policies both in the past and in the present. Although important work remains to be done, “None is Too Many” has undoubtedly influenced a more open immigration policy for those most in need.

Abella was an active member of the Jewish community. He was the director of the New Israel Fund, the chairman of the Holocaust Documentation Project, the president of the Canadian Jewish Congress, and the Schiff Chair of Canadian Jewish History at York University. His Judaism was a defining feature of his scholarship and the practice of Tikkun Olam pulsated throughout his work. Abella viewed history as a call to action. “We can, indeed we must, do better.”

As an academic, Abella’s deep commitment to this humanistic approach to scholarship was reflected in an impressive list of accolades. He was named a member of the Order of Canada, served as the President for the Academy of Arts and Humanities for the Royal Society of Canada, and was awarded the Queen Elizabeth II Golden Jubilee Medal. For his “contribution to documenting the story of Jewish Canadians, and his commitment to the principles of social justice and tolerance” Abella was named a member of the Order of Ontario.

Despite his academic prominence, Abella never failed to make time for emerging scholars. When I was preparing my first historical graphic novel for publication Abella was kind enough to write the introduction. I was making comic books about history and Abella took the time to read my work and consider its merits, despite what he called its “unconventional” form. I remain deeply moved by both his encouragement and excitement. This generosity towards up-and-coming academics and a scholarly curiosity to engage with new forms were hallmarks of who Abella was as a person.

Abella leaves behind his wife, Supreme Court Justice Rosalie Silberman Abella, his sons Jacob and Zachary, and a generation of historians committed to learning the lessons of the past and leaving the present a little bit better than they found it. May his memory be a blessing.

Winnipeg-born Jamie Michaels is the author of two graphic novels: “Canoe Boys” and “Christie Pits”. He is currently working on his doctorate in Israeli-Palestinian relations at the University of Calgary

Features

History of a Holocaust Survivor Turning Eighty

By HENRY SREBRNIK On July 19, I turn 80 years old. This is indeed a milestone, but for me, an even bigger one was just being born. My parents were Holocaust survivors, and I found out just a few months ago that, technically, so am I. My parents were from Czestochowa, Poland, where I was born in 1945. By 1943 most Jews in the city, including their own families, had been murdered by the Nazis, at Treblinka, and after the uprising in the Jewish ghetto, my parents, by now married, became slave labour in a major Nazi munitions plant, the HASAG-Pelcery concentration camp, in the city.

The Russian army liberated Czestochowa January 16-17, 1945, and I was born July 19, six months later. You can do the math. My mother was emaciated and didn’t even know she was pregnant, but another month, and it would have been obvious, and she would have been killed. (I never asked how this happened but found out when listening to her testimony for the Shoah Foundation in 1995. The men and women were housed in different barracks, but one night the Germans were delousing one of the buildings and allowed married couples to sleep together in the other.)

In 1945 the 9th of Av fell on July 19, and the Jewish world had just gone through our worst period in history. I was born in a makeshift hospital at the Jasna Gora, the famed Pauline Catholic monastery in the city. The actual city hospital had been destroyed in the fighting. It is home to the Matka Boska Czestochowska, (“the mother of God”), a very beautiful and large icon of Mary and the baby Jesus. Other women giving birth were surprised and one said, “Ona jest Zydowka” (She’s a Jew). So, though I am a proud Polish Jew, this could only have helped! The doctor who delivered whispered to my mother that he was Jewish but added that he wanted it kept quiet because he wasn’t going to leave Poland. It also took awhile for a mohel to come to the city for me.

The next few years were spent in Pocking-Waldstadt, a DP camp in the American zone in Bavaria, Germany, and then on to Pier 21 in Halifax and Canada. We lived in Montreal, though at home we were to all intents and purposes in Czestochowa, Jewish Poland.

As I was packing up my books in May because we all had to vacate our offices for the summer due to repairs in our building, I came across a book that I had never read – I don’t even recall where I got it — by the Polish historian Lucjan Dobroszycki, Survivors of the Holocaust in Poland: A Portrait Based on Jewish Community Records 1944-1947 (Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe, 1994). Chapter 5 is comprised of “Lists of Jewish Children Who Survived,” in alphabetical order. I am listed on p. 146 (Heniek Srebrnik, 1945). I sent in a form to the Claims Conference in New York informing them. So, at age 80, I’ve become a Holocaust survivor! Compared to that start, the next decades have been easy street! As the Aussies say, “no worries! But the Jewish world has grown darker. Like many others, were I to write a memoir, I’d call it From Hitler to Hamas.

I grew up in Montreal, and have lived in Calgary and Charlottetown, as well as London, England, and four American cities. But I’ve only been to Winnipeg twice, in 1982 and, more dramatically, the weekend of Sept. 7-10, 2001. I presented a paper on “Birobidzhan on the Prairies: Two Decades of Pro-Soviet Jewish Movements in Winnipeg,” to a conference on “Jewish Radicalism in Winnipeg, 1905-1960,” organized by the Jewish Heritage Centre of Western Canada. I left the morning of Sept. 11. An hour into the flight to Toronto we were told all airplanes had to land at the nearest major airport. I spent the next three days in Sault Ste. Marie, Ont., with fellow passengers. We mostly watched the television reporting on the 9/11 catastrophe.

Though an academic, I have always written for newspapers, including Jewish ones, in Canada and the United States. Some, like the Jewish Free Press of Calgary, the Jewish Tribune of Toronto, and the previous version of the Canadian Jewish News, no longer exist, which is a shame. Fortunately, the Jewish Post still does.

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.

Features

Why Prepaid Cards Are the Last Refuge for Online Privacy in 2025

These days, it feels like no matter what you do online, someone’s watching. Shopping, streaming, betting, even signing up for something free—it’s all tracked. Everything you pay for with a normal card leaves a digital trail with your name on it. And in 2025, when we’re deep into a cashless economy, keeping anything private is getting harder by the day.

If you’re the kind of person who doesn’t want every little move tied to your identity, prepaid cards are one of the only real options left. They’re simple, easy to get, and still give you a way to spend online without throwing your info out there. One card in particular, Vanilla Visa, is one of the better picks because of how widely Vanilla Visa is accepted and how little personal info it needs.

Everything’s Online, and Everything’s Tracked

We used to pay for stuff with cash. Walk into a store, hand over some bills, leave. No names, no records. That’s gone now. Most stores won’t even take cash anymore, and the ones that do feel like the exception. The cashless economy is here whether we like it or not.

So what’s the problem? Every time you swipe or tap your card, or pay with your phone, someone’s logging it. Your bank saves the details. The store’s system saves it. And a lot of times, that data gets sold or shared. It can get used to target you with ads, track what you buy, where you go, and when you do it.

It’s not just companies either. Apps collect it. Hackers try to steal it. Some governments keep tabs too. And if you’re using the same card everywhere, it all gets connected pretty fast.

Why Prepaid Cards Still Matter

Prepaid cards are one of the only ways to break that chain. You go to a store, buy one with cash, and that’s it. No bank involved. No name. You just load it up and use it. And because Vanilla Visa is accepted on most major websites, you can use it just like any normal card.

You’re not giving out your real name or tying it to your main account. That means when you pay for something, it’s not showing up on your bank statement. It’s not getting saved under your profile. You’re basically cutting off the trail right there.

Why Vanilla Visa Stands Out

There are a few different prepaid card brands out there, but Vanilla Visa is probably the most popular. You can grab one at grocery stores, gas stations, pharmacies—almost anywhere. And once you’ve got it, you can use it on pretty much any site where Vanilla Visa is accepted.

No long setup. No personal info. You don’t need to register it under your name. You just pay, go online, and spend the amount that’s on the card. When it runs out, you toss it and move on. No trace.

This makes it great for anyone who wants to sign up for a site without attaching their real identity. People use it for online gaming, streaming, subscriptions, or just shopping without giving out their main card info.

The Good and the Bad

There are some solid upsides to using a prepaid card:

- You don’t need a bank account

- You don’t give out your name or address

- It’s easy to budget since you can’t spend more than you loaded

- Most major sites take them, especially where Vanilla Visa is accepted

But there are a few downsides too:

- You can’t reload the card. Once it’s empty, it’s done

- You can’t use it to get money out, like at an ATM

- Some cards have small fees or expiration dates, so don’t let them sit too long

- A few sites want a card tied to a name and billing address, which doesn’t work here

- If you lose it or someone steals the number, you’re probably not getting the money back

So yeah, prepaid cards aren’t perfect. But if privacy is the goal, they’re still one of the few things that actually help.

Real Ways People Use Them

Let’s say you’re trying out an online casino. You don’t want your bank seeing it. You don’t want it on your statement. You walk into a Walgreens, buy a Vanilla Visa with a hundred bucks in cash, then use it to make your deposit. Done. The casino sees a card, but not your name.

Or maybe you’re signing up for a new subscription. Could be a video platform, a magazine, whatever. You don’t want it auto-charging your main card every month or sharing your info with advertisers. Use a prepaid card, and it stays off the radar.

Even if you’re just buying something from a site you don’t totally trust, using a card that isn’t tied to your real money is a smart move.

Will These Cards Still Be Around?

That’s the thing people are starting to worry about. Some stores have started asking for ID when you buy higher-value prepaid cards. And there’s talk in some countries about requiring people to register cards before using them.

Governments don’t like anonymous money. Companies definitely don’t. There’s a chance that in the future, prepaid cards will be harder to get or come with new rules.

But for now, they still work. You can still walk into a store with cash and walk out with a prepaid card. And as long as Vanilla Visa is accepted at the places you shop, you’ve got a way to stay private.

Bottom Line

If you’re living in 2025 and trying to protect your privacy online, prepaid cards are one of the last easy options. The cashless economy makes it almost impossible to pay without leaving a record, but prepaid cards break that pattern. They don’t ask for your name. They don’t track your habits. And they don’t leave a trail if you use them right.

They won’t fix everything. They don’t keep you completely invisible. But they give you a level of control that’s hard to find now. In a world that wants to watch your every move, that still counts for something.

Features

Winkler nurse stands with Israel and the Jewish people

By MYRON LOVE Considering the great increase in anti-Semitic incidents in Canada over the past 20 months – and the passivity of government, federally, provincially and municipally, in the face of this what-should-be unacceptable criminal behaviour, many in our Jewish community may feel that we have been abandoned by our fellow citizens.

Polls regularly show that as many as 70% of Canadians support Israel – and there are many who have taken action. One such individual is Nelli Gerzen, a nurse at the Boundary Trails Health Centre (which serves the communities of Winkler and Morden in western Manitoba). Three times in the past 20 months, Gerzen has taken time off work to travel to Israel to support Israelis in their time of need.

I asked her what those around her thought of her trips to Israel. “My mother was worried when I went the first time (November 2023),” Gerzen responded, “but, like me, she has trust in the Lord. My friends and colleagues have gotten used to it.”

She also reports that she is part of a small group of fellow believers that meet online regularly and pray for Israel.

Gerzen is originally from Russia, but grew up in Germany. Her earliest exposure to the history of the Holocaust, she relates, was in Grade 9 – in Germany. “My history teacher in Germany in Grade 9 went into depth with the history of World War II and the Holocaust,” she recalls. “It is normal that all the teachers taught about the Holocaust but she put a lot of effort into teaching specifically this topic. We also got to watch a live interview with a Holocaust survivor.”

What she learned made a strong impression on her. “I have often asked myself what I would do if I were living in that era,” she says. “Would I have been willing to hide Jews in my home? Or risk my life to save others?”

Gerzen came to Canada in 2010 – at the age of 20. She received her nursing training here and has been working at Boundary Trails for the last three years.

“I believe in the G-d of Israel and that the Jews are his Chosen People,” she states. “We are living at a time of skyrocketing anti-Semitism. Many Jews are feeling vulnerable. I felt that I had to do something to help.”

Gerzen’s first trip to Israel was actually in 2014 when she signed onto a youth tour organized by a Christian group, Midnight Call, based in Switzerland. That initial visit left a strong impact. “That first visit changed my life,” she remembers. “I enjoyed having conversations with the Israelis. The bible for me came to life. Every stone seemed to have a story.”

She went on a second Midnight Call Missionaries tour of Israel in 2018. She went back again on her own in the spring of 2023. After October 7, she says, “I couldn’t sit at home. I had to do something.”

Thus, in November 2023, she went back to Israel, this time as a volunteer. She spent two weeks at Petach Tikvah cooking meals for Israelis displaced from the north and the south as well as IDF soldiers. She also spent a day with an Israeli friend delivering food to IDF soldiers stationed near Gaza. She notes that she wasn’t worried so close to the border.

“I trusted in the Lord,” she says. “It was a special feeling being able to help.”

Last November, she found herself at Kiryat Shmona (with whom our Jewish community has close ties), working for two weeks alongside volunteers from all over the world cooking for the IDF.

On one of her earlier visits, she recounts, a missile struck just a few metres from the kitchen where the volunteers were working. There was some damage – forcing closure for a few days while repairs were ongoing, but no injuries.

In January, she was back at Kiryat Shmona for another two weeks cooking for the IDF. She also helped deliver food to Metula on the northern border. This last time, she reports, there was a more upbeat atmosphere, “even though,” she notes, “the wounds are still fresh. It was quieter. There were no more missiles coming in.

“Israelis were really touched by the presence of so many of us volunteers. I only wish more Christians would stand up for Israel.

“It was really moving to hear people’s stories first-hand.”

She recounts the story of one Israeli she met at a Jerusalem market who fought in the Yom Kippur war of 1973, who was the only survivor of the tank he was in.

“This guy lost so much in his life, and he was standing there telling the story and smiling, just trying to live life again,” she says. “The people there are so heartbroken.”

Back home, she has been showing her support for Israel and the Jewish people by attending the weekly rallies on Kenaston in support of the hostages whenever she can.

She is looking forward to playing piano at Shalom Square during Folklorama.

Nelli Gerzen doesn’t know yet when she will be returning to Israel – but it is certain to be soon. “This is my chance to step up for the truth,” she concludes. “I know that supporting Israel is the right thing to do. When I am there, it feels like my heart is on fire.”