Features

The Fraught Future of Jewish Studies

By Henry Srebrnik Between 1969, when the Association for Jewish Studies (AJS) was founded by forty-seven scholars in Boston, and now, the field of Jewish studies has enjoyed a meteoric expansion. The association, as David Biale, Professor Emeritus of Jewish History at the University of California, Davis, has noted in the winter 2024 issue of the Jewish Review of Books (JRB), it has some 1,800 members, and programs or individual positions exist at virtually every major North American university.

Benefiting from the postwar diminishment of antisemitism and the assimilation of Jews to American society, the scholarly study of the Jews found homes in university departments such as history, religious studies, and comparative literature.

Could that golden age have come to an end on October 7, 2023? “The sudden explosion of anti-Israelism, with its close cousin, antisemitism, has rendered the position of Jewish studies precarious.” It is too soon to know for sure, he states, “but it is hard to avoid the suspicion that something fundamental shifted on that Black Sabbath and its aftermath, not only in Israel but here in America.”

Jewish Studies programs at American (and Canadian) universities, with seed money provided by Jewish philanthropists, sprang up after the 1967 Six-Day War. And at first its faculty were “pro-Israel.” But Jewish communities never had control of these programs. And as the initial cohort of academics retired, their replacements were different – because the hiring process was, of course, largely in the hands of non-Jewish faculty in the humanities. So the successful candidates were more in line with the new zeitgeist of “interrogating” the “Zionist narrative” and giving prominence to non- or anti-Zionist perspectives among American Jews.

This was inevitable. Even the AJS has moved in this direction. (I am a member and have given papers at AJS conferences.) These programs and departments are, in the final analysis, at best “neutral” and agnostic on the Middle East and Israel.

Daniel B. Schwartz is a professor of history and Judaic studies at George Washington University in Washington, DC. In that same issue of the JRB, he recounted that on Oct. 9, a statement from the Executive Committee of the AJS arrived in his inbox. The heading of the email read simply, “Statement from the AJS Executive Committee.”

The statement was about the events of the previous weekend, but the email’s content-free subject line turned out to be symptomatic of what followed. “The members of the AJS Executive Committee,” it said, “express deep sorrow for the loss of life and destruction caused by the horrific violence in Israel over the weekend. We send comfort to our members there and our members with families and friends in the region who are suffering.” In a statement by the AJS, why word “Jews” was nowhere to be found.

“That we have come to the point where the AJS has to resort to such anodyne language,” he asserted, “is truly mind-boggling to me, and frankly shameful.” Why did the half-dozen distinguished scholars who form the Executive Committee of the AJS “feel obligated to obfuscate about the terrible events to which they were ostensibly responding?”

No wonder then, as Mikhal Dekel, Professor of English and the director of the Rifkind Center for the Humanities and Arts at the City College of New York, remarked, “For some of my Jewish colleagues, Israel and Israelis have crossed a threshold to become objects of hatred and disgust that mountains of intellectualized and reasoned essays cannot conceal. These emotions were on display on the very day of October 7, even before a single Israeli soldier entered Gaza.” Decades of BDS (Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions) and other anti-Israel activism “around me hadn’t prepared me for that.”

Certainly the place of Jewish and Israeli-related courses in the wider world of the humanities will decline dramatically, as “anti-Zionism” takes hold across higher education. For example, Cary Nelson, Jubilee Professor of Liberal Arts and Sciences at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, told us in the February issue of Fathom, a British publication, that “after nearly two decades of trying, the Modern Language Association’s annual meeting finally succeeded in putting this academic group on record opposing Israel.”

The MLA represents about twenty thousand North American literature and foreign language faculty and graduate students. “This time they were riding a wave of anti-Zionist hostility that has swept the academy since Hamas wantonly slaughtered over 1,200 Israelis and foreign visitors in the largest antisemitic murder spree since the Holocaust.”

Nelson reported that at one MLA meeting, “when a member from Haifa referenced Hamas’s sexual violence there was reportedly audible hissing among the anti-Zionist members attending. Was it unacceptable to impugn the character of Hamas terrorists? Were some MLA members on board with Hamas denials?”

A recent trend has seen Jewish academics in Jewish Studies programs at universities like Berkely, Brown, Dartmouth, Emory, Harvard and elsewhere publish widely noticed books that are, at best, “non-Zionist” and in fact sympathetic to the naqba narrative of Arab-Jewish relations during and after the formation of Israel. But why should we be surprised? They are embedded in institutions where the “woke” Diversity-Equity-Inclusion ideology now prevails.

The new book by historian Geoffrey Levin, assistant professor of Middle Eastern and Jewish studies at Emory University in Atlanta, “Our Palestine Question: Israel and American Jewish Dissent, 1948-1978,” is one such work. He writes sympathetically about an early, formative era before American Jewish institutions had unequivocally embraced Zionism.

“The No-State Solution: A Jewish Manifesto” by Daniel Boyarin, the Taubman Professor of Talmudic Culture and rhetoric at the University of California, Berkeley, aims to drive a wedge between the “nation” and the “state,” and “recover a robust sense of nationalism that does not involve sovereignty.”

“The Necessity of Exile: Essays from a Distance” by Shaul Magid, the Distinguished Fellow in Jewish Studies at Dartmouth, calls for “recentering” Judaism over nationalism and “challenges us to consider the price of diminishing or even erasing the exilic character of Jewish life.”

Derek Penslar, an historian at Harvard, last year published “Zionism: An Emotional State,” which described the situation in the West Bank as apartheid, even though over 90 per cent of Palestinians there are governed not by Israel but by the Palestinian Authority. The point of calling Israel an apartheid regime is to suggest that it must go the way of white-led South Africa.

They are among a spate of books dealing with the history of Jewish dissent over Israel and Zionism, including “The Threshold of Dissent: A History of American Jewish Critics of Zionism” by Marjorie N. Feld, and “Unsettled: American Jews and the Movement for Justice in Palestine” by Oren Kroll-Zeldin.

A cold khamsim is blowing across Jewish Studies in academia.

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island in Charlottetown, PEI.

Features

Why casinos reject card payments: common reasons

Online casino withdrawals seem simple, yet many players experience unanticipated decreases. Canada has more credit and debit card payout refusals than expected. Delays or rejections are rarely random. Casino rules and technical processes are rigorous. Identity verification, banking regulations, bonus terms, and technological issues might cause issues.

Card payment difficulties can result from insufficient identification verification. Canadian casinos must verify players’ identities before accepting card withdrawals. If documentation are missing, obsolete, or confusing, the request may be stopped or denied until verified.

Banks and card issuers’ gaming policies are another aspect. Some Canadian banks limit or treat online casino payments differently from card refunds. In such circumstances, the casino may recommend a more reliable withdrawal method.

For Canadian players looking to compare bonus terms and payout conditions, check https://casinosanalyzer.ca/free-spins-no-deposit/free-chips. This article explores the main reasons Canadian casinos reject card payouts, from KYC hurdles to bank-specific restrictions, so you know exactly what to watch for.

Verification Issues: Why Identity Checks Matter

KYC rules must be activated by licensed casinos. Players need to submit proof of their identity, address and age. If any documentation is missing, expired or unclear, the withdrawal will be denied. In Canada, for instance, authorities like the AGCO or iGaming Ontario have been cracking down on KYCs by demanding that submitted documents – whether photo ID, utility bills or bank statements – be consistent with all account details.

Common errors are submitting screenshots, cropped photos or documents with names, dates or addresses that aren’t entirely visible. Just the slightest differences in spelling or abbreviations or formatting can get these blocks triggered.

Another possibility is that the account was red flagged if previous withdrawals were already made without partial verification. Keeping precise, readable documents helps facilitate approvals and cuts through delays and frustrating red tape, as Canadian gamblers access their winnings both safely and quickly.

Timing Matters

Verification isn’t always instant. Documents being submitted during the busiest times, or on weekends or holidays can only prolong that approval process, and the withdrawal sitting pre-approved – or refused for that matter – until the casino reviews the paperwork. A lot of players feel disappointment not due to mistakes, but only for that a verification team still hasn’t checked their documents! This can be especially frustrating when winnings come from free chips or bonus play and players are eager to cash out.

Keep personal information current and only submit clear legible files to reduce the processing time. Ensure that any scans or photos are sharp, fully visible and there is no detail missing. Preventing Gaffes With submission guidelines to read over ahead of time and directions for following them exactly, verification issues can often be significantly minimized, avoiding delay in accessing winnings and making the lie down withdrawal process that much smoother at Canadian online casinos.

Banking Restrictions and Card Policies

Not all credit or debit cards are eligible for casino withdrawals. Many Canadian banks restrict transactions related to gambling. For example, prepaid cards, virtual cards, or certain credit cards may allow deposits but block withdrawals. Even if deposits work, a payout can fail if the bank refuses incoming gambling credits.

Cards issued outside Canada can also be declined due to international processing rules. Currency conversion restrictions may prevent a CAD payout to a USD card, depending on the bank’s policies.

Banks keep an eye on abnormal or frequent transactions. Online casinos can flag large or multiple withdrawals as suspicious and in such cases may impose temporary blocks on withdrawals or outright decline the withdrawal until the issuing bank confirms them with its account holder. Contacting your bank in advance will avoid any surprises and make withdrawals go more smoothly. What to consider when using your card in Canada:

- Check if your card type supports gambling withdrawals (prepaid, virtual, and some credit cards may not).

- Confirm whether your bank allows international online casino payouts.

- Be aware of currency conversion restrictions.

- Monitor withdrawal frequency to avoid triggering fraud alerts.

- Contact your bank ahead of time to authorize or clarify online gambling transactions.

- Keep alternative withdrawal methods ready, such as e-wallets or bank transfers.

Being aware of these constraints prevents Canadian players from having declined payouts, delays and waste of time when it comes to handling the casino money properly.

Wagering Requirements and Bonus Conditions

Many Canadians chase casino bonuses, including deals built around free chips, but these offers always come with conditions, Wagering requirements usually require players to bet a multiple of the bonus before withdrawing. Attempting a payout before meeting these conditions will be automatically declined. Not all games contribute equally: slots often count 100%, table games 10–20%, and certain features nothing at all.

Misinterpretation of this, can make it appear as though a withdraw should be valid, while the casino believes there are unmet bonus requirements. Some casinos also impose a minimum withdrawal amount and will cap card payouts. And if you have more than the minimum in your account, a limit set off by your bonus could limit withdrawal. By testing these issues early on, you can save yourself a lot of aggravation. How to manage bonus conditions effectively:

- Have a close look at the terms of the bonus – check out wagering requirements, game contribution and time limits.

- Track your progress – note how much of the bonus has been wagered and which games contribute most.

- Plan your gameplay – prioritize slots or eligible games to efficiently meet wagering.

- Check withdrawal limits – ensure your balance meets minimums and bonus-specific caps.

- Avoid early withdrawals – never attempt a cash-out before meeting all conditions.

- Use trusted sources – platforms like CA CasinosAnalyzer can clarify real requirements and prevent surprises.

Following these steps helps players meet bonus conditions without stress and makes bankroll management smoother.

Features

What is the return on investment of US military spending on Israel?

By GREGORY MASON A recurring theme of Israel’s critics is that were it not for US spending on its war machine, it would be unable to wage genocide. I will leave the genocide issue (sic, I mean non-issue) aside as it has been well covered here and here.

Of course, right now (March 11), the war is going well for Israel and the US. In fact, the Israeli and American air forces are showing a level of coordination enabled by decades of close cooperation between the two militaries. I recall a conversation with an IDF colonel, the commander of a base near Eilat, in 2010, during a mission that gave participants access to high-level military briefings. Tensions between Israel and the US had soured, as they periodically do, and I asked whether this ebb and flow in political posturing affected military operations. The colonel said political leaders come and go, but the cooperation between the Israeli and American militaries is very tight. To quote him, “they need us as much as we need them. We are their eyes and ears in this part of the world.”

Many on both the right and left call for the US to disengage from Israel, especially with respect to defence spending. First, let us look at facts.

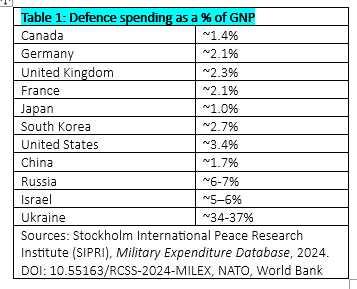

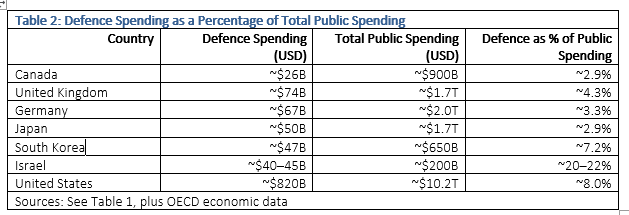

Table 1 readily shows the impact of the war in Ukraine, with Russia’s spending also reflecting wartime demands. Israel’s total commitment of 5-6% of GDP amounts to $45 billion in defence spending, reflecting its perpetual need to defend itself and maintain a permanent reserve force. Table 2 elaborates on defence spending as a share of public spending. Unlike other countries that have been free riding under the US military umbrella (and Canada is the most egregious of the lot), Israel has made very substantial commitments to its own defence. The $3.8 billion spent on hardware for US equipment is a fraction of Israel’s total defence budget of about $43 Billion. All U.S. financial aid to any country for military hardware must be spent on U.S.-manufactured equipment by law.

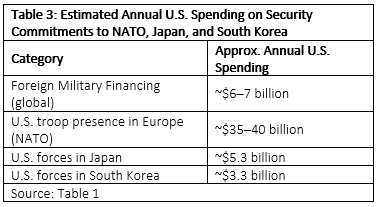

Critics of US defence funding for Israel miss two key points. First, as Table 3 shows, financing sent to Israel does not involve troop deployment. Israel does not want the US to station troops within its borders. The costs of maintaining troop deployments and all the associated support costs for NATO, Japan, and South Korea are orders of magnitude higher than the financing for the hardware it provides to Israel.

Second, and the current joint US/Israeli operations in Iran bear this out, Israel has dramatically improved the equipment platforms it purchased. Examples include:

- The F-15 has benefited from Israeli wartime use, resulting in major improvements, including a redesigned cockpit layout, increased range through fuel redesign, improved avionics, new weaponry, helmet-mounted targeting, and structural strengthening.

- Because Israel was an early partner in the fighter’s development and had access to its top-secret software suite, the Israeli version of the F-35 is a radically different plane than the model delivered. Improvements include increasing operational range, embedding advanced air defence detection, and integrating the fighter with Israel’s defence network, creating extensive system integration. This proved instrumental in the rapid establishment of air superiority in the 12-day war in 2025.

- The THAAD (Terminal High Altitude Area Defence) program has benefited from a joint research and development relationship between Israel and the U.S.

- Finally, Iron Dome has contributed to U.S. air defence development, particularly the Tamir interceptor technology, battle management, target discrimination, and the development of a layered air defence system.

No senior military or political official questions the return on investment American gains by funding Israel’s acquisition of U.S. military hardware.

Features

Why Returning Players Often Stick to a Few Favorite Games on Platforms Like Gransino Casino

Many online casino players develop clear preferences over time, and Gransino Casino highlights how familiar games often become the center of regular play sessions.

Online casinos typically offer large catalogs filled with hundreds of different slot titles. While this variety allows players to explore new experiences, many returning users gradually settle on a smaller group of games that they revisit regularly. This pattern appears across many digital gaming environments, where familiarity often becomes just as important as novelty.

Platforms such as Gransino Casino demonstrate how this behavior emerges in practice. Even though players have access to many different titles, returning visitors frequently gravitate toward games they already know and understand.

Familiar mechanics reduce learning time

One reason players return to the same games is that they already understand how those titles work. Each slot game has its own rules, bonus features, and payout structure. When a player first opens a new title, they often need a few minutes to understand the paytable, special symbols, and feature triggers.

Once that learning process has taken place, the game becomes easier to approach in future sessions. Players do not need to spend time reviewing instructions or exploring unfamiliar mechanics. Instead, they can begin playing immediately with a clear sense of how the game operates.

On platforms like Gransino Casino, this familiarity can make certain titles stand out as reliable choices. When players know what to expect from a game, the experience often feels smoother and more predictable during short play sessions.

Personal preferences shape long-term choices

Another factor influencing player behavior is personal preference. Some players enjoy specific visual themes such as mythology, adventure, or classic fruit machine designs. Others may prefer particular gameplay features, such as free spins, cascading reels, or bonus rounds.

Over time, players tend to identify the games that best match these preferences. Once they find titles that align with their interests, they are more likely to return to those games rather than start the search process again.

This pattern can be seen on Gransino Casino, where players browsing the lobby may explore different titles at first but eventually settle on a smaller group of favorites that suit their individual style.

Habit formation in digital gaming

Habit formation also plays a role in why players repeatedly choose the same games. In many digital environments, users develop routines that guide how they interact with a platform. This behavior is visible across streaming services, mobile games, and online casinos.

Once a player has established a routine, returning to familiar content often becomes part of that pattern. For example, a player might log in and immediately open the same slot they played during previous sessions. The familiarity of the interface, symbols, and features can make the experience feel more comfortable.

Platforms like Gransino Casino support this behavior by maintaining consistent game availability and allowing players to locate previously played titles easily within the lobby.

Exploration still remains part of the experience

Although many players develop favorite games, exploration remains an important part of the online casino experience. New titles continue to appear on casino platforms, introducing different mechanics, themes, and visual styles.

Players often alternate between their familiar choices and occasional experimentation with new games. A player might return to a favorite slot for most sessions while occasionally trying recently released titles to see if they offer something interesting.

The wide selection available on Gransino Casino allows this balance between familiarity and discovery. Players can continue returning to the games they enjoy while still having the option to explore new additions within the platform’s catalog.

Ultimately, the tendency to revisit favorite games reflects how players build their own routines within digital entertainment environments. Familiar titles offer a comfortable starting point, while new releases provide opportunities for occasional exploration, creating a mix of consistency and variety within each player’s experience.