Features

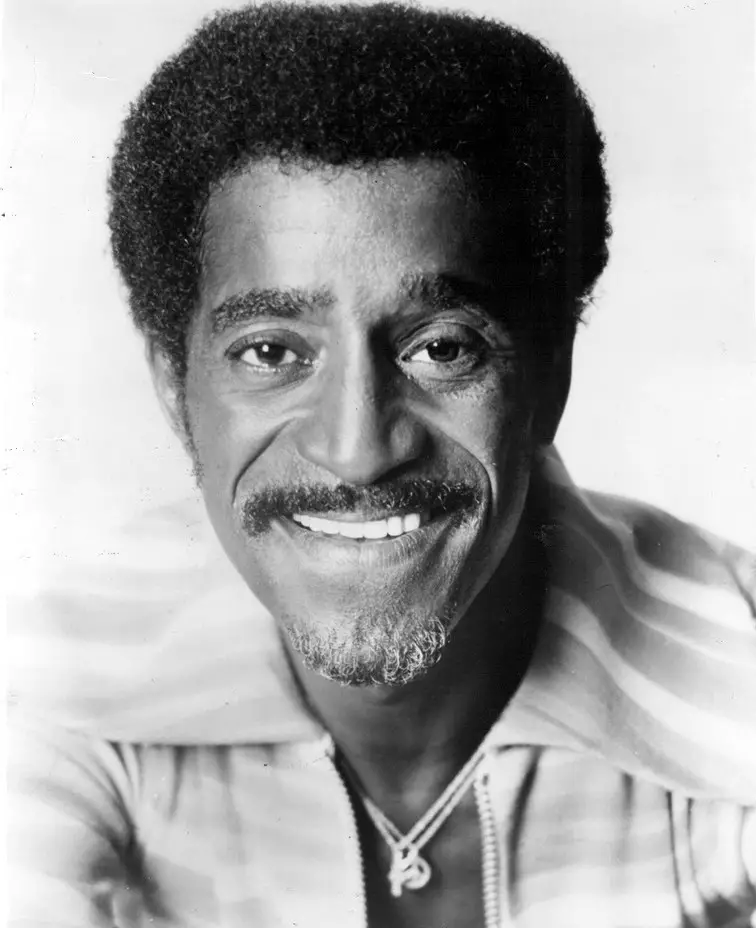

The real story behind Sammy Davis Jr.’s conversion to Judaism

Jewish comedians made racist jokes about him. Some Black audiences booed him. But his faith was genuine

By Beth Harpaz February 23, 2023

(This story was originally published in the Forward. Click here to get the Forward’s free email newsletters delivered to your inbox.)

Sammy Davis Jr. was a short and skinny Black man with one eye. His wife was white, his mother was Puerto Rican and he was a convert to Judaism. In the crass and racist world of mid-20th century comedy, he was a walking punchline, even in his own routines.

“When I move into a neighborhood, I wipe it out,” was his standard self-deprecating gag. The line received knowing laughs in the 1950s and ’60s when many towns forbade property sales to Blacks and Jews, and whites often fled when Black families moved into their neighborhoods.

Jokes by his fellow entertainers were crude. In a live skit at the Sands in Las Vegas in 1963, Dean Martin physically lifted Davis up (he weighed a mere 120 pounds) and said, “I’d like to thank the NAACP for this wonderful trophy.” At a Friars Club roast, comedian Pat Buttram said that if Davis showed up in Buttram’s home state of Alabama, folks “wouldn’t know what to burn on the lawn.”

Jewish comedians got their licks in, too. Milton Berle cross-dressed as Davis’ white wife, May Britt, and sang, to the tune of “My Yiddishe Mama,” “My Yiddish Mau-Mau,” a reference to an anti-British rebellion in Kenya.

At another roast, Joey Bishop said he’d “never been so embarrassed” in his life as when he met Davis in synagogue. When the rabbi came in, Bishop said, “Sammy jumped up and hollered, ‘Here come the judge!’”

This cringeworthy line was delivered by Davis himself in a show at the Copa: “I don’t know whether to be shiftless and lazy, or smart and stingy.”

Some of these jokes implied that it was preposterous for a Black man to convert to Judaism. But for Sammy Davis Jr., being Jewish “was the most logical thing in the world,” historian Rebecca L. Davis told me. “Over and over again, he made this analogy between being Jewish and African American. He was very admiring of the Jewish millennia-long struggle against oppressors and overcoming all kinds of obstacles.” He saw himself as “an outsider and very marginalized, and he could see in the Jewish experience a similarity that really drew him in emotionally.”

Davis, a history professor at the University of Delaware (and no relation to Sammy), has done extensive research on the entertainer’s conversion, his career and how he was perceived. Her article, “‘These Are a Swinging Bunch of People’: Sammy Davis, Jr., Religious Conversion, and the Color of Jewish Ethnicity,” appeared in the American Jewish History journal in 2016, and she included a chapter about him in her 2021 book, Public Confessions: The Religious Conversions That Changed American Politics. Her take is that Davis was not only one of the most successful entertainers of the 20th century despite the many racist barriers in his way, but that his Jewish faith was utterly genuine.

The fateful accident

Davis lost his eye when he crashed his car driving home to California from Las Vegas in November 1954. One of several stories about what sparked Davis’ path to conversion originates with the aftermath of the accident. He wrote in his 1965 autobiography, Yes I Can, that his friends Tony Curtis, who was Jewish, and Janet Leigh, who was not, arrived at the hospital and Leigh gave him a religious medal with St. Christopher on one side and a Star of David on the other. “Hold tight and pray and everything will be all right,” Leigh told him.

Davis later told Alex Haley in a Playboy interview that he gripped the object so tightly that the Star of David left a scar on his hand, “like a stigmata.” He took it as a sign that he should convert.

Davis also felt that he owed his career to a Jewish man, Eddie Cantor, who ironically had been one of vaudeville’s best-known blackface performers; Cantor’s act earned him a spot with the Ziegfeld Follies. Decades later, Cantor gave Davis his first big break, a solo televised appearance on the Colgate Comedy Hour in 1952, and became a father figure to him. “He saw Cantor’s Jewishness as part of what made Cantor a good person,” said Rebecca Davis.

In another version of how his car accident led to his conversion, Sammy Davis said that a mezuzah Cantor gave him had mistakenly been left behind in a hotel room the day of the crash. That story transformed the mezuzah “into a talisman,” Rebecca Davis observed, another signpost on the road to his conversion.

Identifying as a Jew

In his memoir, Sammy Davis recalled Rabbi Max Nussbaum, of Temple Israel in Hollywood, telling him, “We cherish converts, but we neither seek nor rush them.” But he began to publicly identify as Jewish before formally converting. In 1959 he refused to film scenes for the movie Porgy and Bess on Yom Kippur, while Ebony ran a photo of him holding Everyman’s Talmud.

He also repeatedly compared the oppression of Jews to that of African Americans. In his 1989 book, Why Me?, he wrote that he was “attracted by the affinity between the Jew and the Negro. The Jews had been oppressed for three thousand years instead of three hundred but the rest was very much the same.” When he visited the Wailing Wall in 1969, he said Israel was his “religious home.”

The reception from Black audiences

American Jews by and large loved him, and his reception in the Jewish press, including the Forward, was also positive, Rebecca Davis said. But it was more complicated for Black media. On the one hand, she said, he was “this exemplar of Black success, very wealthy, very famous, very successful” in an era of rampant racism.

On the other hand, there was “confusion and anger” about why — as a prominent Black activist who joined marches, raised money and was the United Negro College Fund’s largest donor — Sammy Davis so often connected the civil rights cause to Judaism. While there were a “disproportionate number of Jews who were passionate about civil rights and were willing to put their personal safety on the line to stand up for civil rights,” at the same time, Jews were part of a “broader American culture that saw African Americans as inferiors. That was the prevailing cultural norm among white people in the 1950s,” Rebecca Davis said. Other critics felt that he had converted to ingratiate himself with whites as a way to get ahead.

And when he “let himself be the joke” as part of the Rat Pack — a loose ensemble of performers that included Dean Martin, Frank Sinatra and Peter Lawford — that “really angered a lot of African Americans who saw him more as performing for white audiences than for Black audiences.”

He formally converted with Britt shortly before their wedding in 1960. She was as serious about it as he was, making sure, even after they were divorced, that their children went to Hebrew school and that their son was bar mitzvahed.

Disinvited from JFK’s inauguration

But their marriage also resulted in one of the most painful episodes of his life, when he was disinvited from John F. Kennedy’s presidential inauguration. The Democratic coalition that elected JFK included Southern white Democrats, and they did not want a Black man married to a white woman performing at the celebration. “They forced Davis out,” Rebecca Davis said. “He was so stung by that. Here he was on stage and on film with Dean Martin and Frank Sinatra and the biggest stars of the day, and they all got to go to the inauguration, but he didn’t.”

That rejection helps explain Davis’ subsequent embrace of Richard Nixon. “Nixon, who was politically very devious, figured he could use Sammy Davis as a token African American supporter by overdoing it and inviting him to sleep in the Lincoln bedroom,” Rebecca Davis said. That made him the first Black man to spend the night as a guest in the White House.

Some African Americans saw Davis’ alignment with Nixon and the Republicans as a betrayal. Harry Belafonte and Sidney Poitier stopped returning his phone calls, Rebecca Davis wrote, and a year or two after he performed at the 1972 Republican National Convention, he was booed at an event organized by Jesse Jackson.

He responded to the boos by saying, “I get it. I understand. But I need you to know, I always did it my way. It’s the only way I’ve got,” Rebecca Davis said. “Then he sang ‘I’ve Gotta Be Me,’ and they gave him a standing ovation.”

A steadfast Jew until the end

His third wife, Altovise, was a churchgoer, but Sammy Davis remained a steadfast Jew until the day he died. Everything he said about Judaism “was said with the utmost sincerity,” Rebecca Davis said. “He never once looked back and said, ‘Oh, that was just a phase I was going through.’ And he never talked about it in terms of his career. He only talked about it as something that spoke to him on a deep level.”

Davis died of throat cancer in 1990 at age 64. Sinatra, Berle, Liza Minnelli, Stevie Wonder, Dionne Warwick and many other celebrities were among thousands of mourners who backed up traffic for 8 miles en route to the funeral at Forest Lawn Memorial Park in LA. Rabbi Allen Freehling presided at the service, but the eulogy was given by Jesse Jackson.

“To love Sammy was to love Black and white, Black and Jew,” he said, “and to embrace the human family.”

The service also included one last standing ovation for Davis, when they played a recording of – what else? – “I’ve Gotta Be Me.”

Beth Harpaz is a reporter for the Forward. She previously worked for The Associated Press, first covering breaking news and politics, then as AP Travel editor. Email: harpaz@forward.com.

This article was originally published on the Forward

Features

Methods of Using Blockchain on Gambling Sites: Explained by Robocat Casino

The world of online gambling is changing and chasing new tools to entertain visitors. Players demand more transparency, faster payouts, and complete control over their money, making traditional casinos seem outdated. Modern websites like Robocat Casino utilize blockchain technology, which is the digital foundation for everything from crypto transactions to provably fair games. If you’re unfamiliar with how casinos use blockchain, we’ll cover it below.

What is Blockchain in a Casino?

Blockchain is a system that records data in a way that cannot be altered. The technology operates using a decentralized ledger shared across multiple computers. Every transaction is recorded in the ledger, which is regularly updated and accessible to all participants.

These properties are useful for gambling sites like Robocat Casino. The digital ledger processes every bet and prevents alteration. As a result, every action is transparent, and players have no doubt about the website’s integrity.

All transactions occur on a decentralized ledger, so there is no central authority that could interfere. This ensures complete anonymity. This privacy has led to an increasing number of players choosing to bet at crypto casinos.

How is This Technology Used in Gambling?

There are several ways users might encounter blockchain technology at sites like Robocat Casino.

- Provably fair games. Traditional online casinos have always been criticized for their fairness, as players doubt whether the odds are truly in their favor. Blockchain technology eliminates this uncertainty. Systems with provably fair games use cryptographic algorithms and publicly accessible hashes to control the outcome of each spin or draw. This limits backend manipulation and ensures transparency between the website and the user.

- Greater anonymity and lower KYC (know your customer) requirements. Not all crypto casinos eliminate the KYC process, but many are more lenient than casinos that exclusively accept fiat transactions. Some sites allow you to play with just a wallet address, without the need for identification documents.

- Cryptocurrency deposits and withdrawals. With blockchain technology, you can forget about the five-day wait for funds to appear in your gaming account. When working with cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin or Ethereum, deposits and withdrawals are almost instantaneous. Interacting with cryptocurrency goes beyond speed. It offers low transaction fees and 24/7 global availability.

- Smart contracts. These are self-executing contracts based on the blockchain. In casinos, they can automate everything from loyalty bonuses to jackpot payouts. Such procedures require no human intervention, eliminating the risk of errors.

- Tokenized loyalty systems. Casinos can issue their own tokens as rewards. This is a cryptocurrency that can be sold or spent on the website. This approach creates real economic value for loyalty programs and motivates users to choose the casino.

The evolution of blockchain will lead to an expanded role at Robocat Casino and other gambling websites. Experts expect the use of decentralized applications (dApps) to increase. These operate on blockchain networks, rather than on a single server, and ensure complete decentralization of casinos. The absence of intermediaries or regulatory bodies will provide players with greater transparency.

Features

BlackRock applies for ETF plan; XRP price could rise by 200%, potentially becoming the best-yielding investment in 2026.

Recently, global asset management giant BlackRock officially submitted its application for an XRP ETF, a piece of news that quickly sparked heated discussions in the cryptocurrency market. Analysts predict that if approval goes smoothly, the price of XRP could rise by as much as 200% in the short term, becoming a potentially top-yielding investment in 2026.

ETF applications may trigger a large influx of funds.

As one of the world’s largest asset managers, BlackRock’s XRP ETF is expected to attract significant attention from institutional and qualified investors. After the ETF’s listing, traditional funding channels will find it easier to access the XRP market, providing substantial liquidity support.

Historical data shows that similar cryptocurrency ETF listings are often accompanied by significant short-term market rallies. Following BlackRock’s application announcement, XRP prices have shown signs of recovery, and investor confidence has clearly strengthened.

CryptoEasily helps XRP holders achieve steady returns.

With its price potential widely viewed favorably, CryptoEasily’s cloud mining and digital asset management platform offers XRP holders a stable passive income opportunity. Users do not need complicated technical operations; they can receive daily earnings updates and achieve steady asset appreciation through the platform’s intelligent computing power scheduling system.

The platform stated that its revenue model, while ensuring compliance and security, takes into account market volatility and long-term sustainability, allowing investors to enjoy the benefits of market growth while also obtaining a stable cash flow.

CryptoEasily is a regulated cloud mining platform.

As the crypto industry rapidly develops, security and compliance have become core concerns for investors. CryptoEasily emphasizes that the platform adheres to compliance, security, and transparency principles and undergoes regular financial and security audits by third-party institutions. Its security infrastructure includes platform operations that comply with the European MiCA and MiFID II regulatory frameworks, annual financial and security audits conducted by PwC, and digital asset custody insurance provided by Lloyd’s of London.

At the technical level, the platform employs multiple security mechanisms, including bank-grade firewalls, cloud security authentication, multi-signature cold wallets, and an asset isolation system. This rigorous compliance system provides excellent security for users worldwide.

Its core advantages include:

● Zero-barrier entry: No need to buy mining machines or build a mining farm, even beginners can easily get started.

●Automated mining: The system runs 24/7, and profits are automatically settled daily.

● Flexible asset management: Earnings can be withdrawn or reinvested at any time, supporting multiple mainstream cryptocurrencies.

●Low correlation with price fluctuations: Even during short-term market downturns, cash flow remains stable.

CryptoEasily CEO Oliver Bruno Benquet stated:

“We always adhere to the principle of compliance first, especially in markets with mature regulatory systems, to provide users with a safer, more transparent and sustainable way to participate in digital assets.”

How to join CryptoEasily

Step 1: Register an account

Visit the official website: https://cryptoeasily.com

Enter your email address and password to create an account and receive a $15 bonus upon registration. You’ll also receive a $0.60 bonus for daily logins.

Step 2: Deposit crypto assets

Go to the platform’s deposit page and deposit mainstream crypto assets, including: BTC, USDT, ETH, LTC, USDC, XRP, and BCH.

Step 3: Select and purchase a mining contract that suits your needs.

CryptoEasily offers a variety of contracts to meet the needs of different budgets and goals. Whether you are looking for short-term gains or long-term returns, CryptoEasily has the right option for you.

Common contract examples:

Entry contract: $100 — 2-day cycle — Total profit approximately $108

Stable contract: $1000 — 10-day cycle — Total profit approximately $1145

Professional Contract: $6,000 — 20-day cycle — Total profit approximately $7,920

Premium Contract: $25,000 — 30-day cycle — Total profit approximately $37,900

For contract details, please visit the official website.

After purchasing the contract and it takes effect, the system will automatically calculate your earnings every 24 hours, allowing you to easily obtain stable passive income.

Invite your friends and enjoy double the benefits

Invite new users to join and purchase a contract to earn a lifetime 5% commission reward. All referral relationships are permanent, commissions are credited instantly, and you can easily build a “digital wealth network”.

Summarize

BlackRock’s application for an XRP ETF has injected strong positive momentum into the crypto market, with XRP prices poised for a significant surge and becoming a potential high-yield investment in 2026. Meanwhile, through the CryptoEasily platform, investors can steadily generate passive income in volatile markets, achieving double asset growth. This provides an innovative and sustainable investment path for long-term investors.

If you’re looking to earn daily automatic income, independent of market fluctuations, and build a stable, long-term passive income, then joining CryptoEasily now is an excellent opportunity.

Official website: https://cryptoeasily.com

App download: https://cryptoeasily.com/xml/index.html#/app

Customer service email: info@CryptoEasily.com

Features

Digital entertainment options continue expanding for the local community

For decades, the rhythm of life in Winnipeg has been dictated by the seasons. When the deep freeze sets in and the sidewalks become treacherous with ice, the natural tendency for many residents—especially the older generation—has been to retreat indoors. In the past, this seasonal hibernation often came at the cost of social connection, limiting interactions to telephone calls or the occasional brave venture out for essential errands.

However, the landscape of leisure and community engagement has undergone a radical transformation in recent years, driven by the rapid adoption of digital tools.

Virtual gatherings replace traditional community center meetups

The transition from physical meeting spaces to digital platforms has been one of the most significant changes in local community life. Where weekly schedules once revolved around driving to a community center for coffee and conversation, many seniors now log in from the comfort of their favorite armchairs.

This shift has democratized access to socialization, particularly for those with mobility issues or those who no longer drive. Programs that were once limited by the physical capacity of a room or the ability of attendees to travel are now accessible to anyone with an internet connection.

Established organizations have pivoted to meet this digital demand with impressive results. The Jewish Federation’s digital outreach has seen substantial engagement, with their “Federation Flash” e-publications exceeding industry standards for open rates. This indicates a community that is hungry for information and connection, regardless of the medium.

Online gaming provides accessible leisure for homebound adults

While communication and culture are vital, the need for pure recreation and mental stimulation cannot be overlooked. Long winter evenings require accessible forms of entertainment that keep the mind active and engaged.

For many older adults, the digital realm has replaced the physical card table or the printed crossword puzzle. Tablets and computers now host a vast array of brain-training apps, digital jigsaw puzzles, and strategy games that offer both solitary and social play options.

The variety of available digital diversions is vast, catering to every level of technical proficiency and interest. Some residents prefer the quiet concentration of Sudoku apps or word searches that help maintain cognitive sharpness. Others gravitate towards more dynamic experiences. For those seeking a bit of thrill from the comfort of home, exploring regulated entertainment options like Canadian real money slots has become another facet of the digital leisure mix. These platforms offer a modern twist on traditional pastimes, accessible without the need to travel to a physical venue.

However, the primary driver for most digital gaming adoption remains cognitive health and stress relief. Strategy games that require planning and memory are particularly popular, often recommended as a way to keep neural pathways active.

Streaming services bring Israeli culture to Winnipeg living rooms

Beyond simple socialization and entertainment, technology has opened new avenues for cultural enrichment and education. For many in the community, staying connected to Jewish heritage and Israeli culture is a priority, yet travel is not always feasible.

Streaming technology has bridged this gap, bringing the sights and sounds of Israel directly into Winnipeg homes. Through virtual tours, livestreamed lectures, and interactive cultural programs, residents can experience a sense of global connection that was previously difficult to maintain without hopping on a plane.

Local programming has adapted to facilitate this cultural exchange. Events that might have previously been attended by a handful of people in a lecture hall are now broadcast to hundreds. For instance, the community has seen successful implementation of educational sessions like the “Lunch and Learn” programs, which cover vital topics such as accessibility standards for Jewish organizations.

By leveraging video conferencing, organizers can bring in expert speakers from around the world—including Israeli emissaries—to engage with local seniors at centers like Gwen Secter, creating a rich tapestry of global dialogue.

Balancing digital engagement with face-to-face connection

As the community embraces these digital tools, the conversation is shifting toward finding the right balance between screen time and face time. The demographics of the community make this balance critical. Recent data highlights that 23.6% of Jewish Winnipeggers are over the age of 65, a statistic that underscores the importance of accessible technology. For this significant portion of the population, digital tools are not just toys but essential lifelines that mitigate the risks of loneliness associated with aging in place.

Looking ahead, the goal for local organizations is to integrate these digital successes into a cohesive strategy. The ideal scenario involves using technology to facilitate eventual in-person connections—using an app to organize a meetup, or a Zoom call to plan a community dinner.

As Winnipeg moves forward, the lessons learned during the winters of isolation will likely result in a more inclusive, connected, and technologically savvy community that values every interaction, whether it happens across a table or across a screen.