RSS

A Greek Holocaust survivor in Vermont knows how to save humanity. He just needs us to listen.

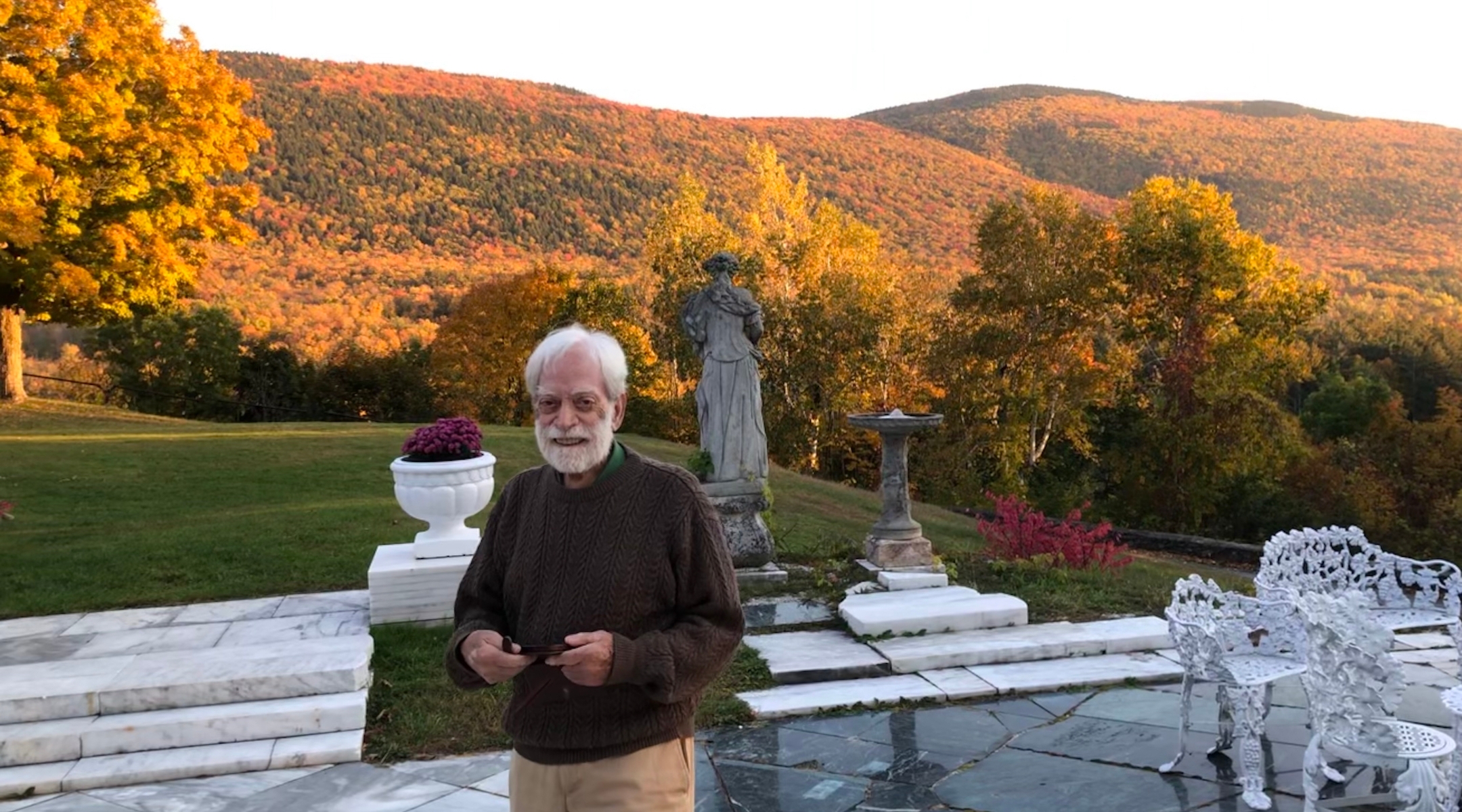

MANCHESTER, Vermont (JTA) – From his seat on the back patio of the Wilburton Inn, Albert Levis can see the fruits of his decades of labor.

It’s fall, and Vermont is full of “leaf peepers,” folks who drive up the East Coast to take in the foliage. And the 30-acre grounds of the Wilburton, which Levis and his family own, are a leaf peeper’s paradise: situated high on a hill overlooking lush valleys of orange and yellow canopies, with grand manors that hold cozy, spacious bedrooms and dining areas. Visitors can attend murder mysteries and dog slumber parties, or host their own weddings and wellness retreats; just down the hill is a Levis family-run farm that hosts concerts and sells fresh-baked bread out of a van. The inn has won several major travel awards.

But Albert isn’t looking at his empire. His eyes are fixed at some point just beyond, as he ponders his grand Formal Theory of Behavior: the one this tourist destination is meant to support, the one he has devoted his life to teaching. The Formal Theory means everything to Albert — and if he could just convince everyone else of its greatness, he believes, then world peace would be at hand.

Albert needs a lot of explanation to get there. He first tries by invoking the great Jewish philosophers Maimonides and Baruch Spinoza.

“Spinoza was a thinker who believed in a universal order,” Levis said. “He was the first to say that there was some grander, universal mechanism at work.” Maimonides, too, was “a great rational thinker,” he says. But neither, Levis believes, truly understood the insight he had, that “the human unconscious” is “an energy transformation engine,” the key to understanding how humans think and process the order of the universe.

This approach isn’t working. Levis tries again, this time by explaining how all this connects to his personal story as one of a very few Greek Jewish Holocaust survivors.

“My research story started as a kid of the Holocaust,” he says, laughing nervously, relaying how he was 6 years old when his family went into hiding, how his father and grandfather were killed by Communist rebels after the war, and how he only avoided capture by disguising himself as a Christian. These experiences, he says, informed his current understanding that all forms of religion and myth, from Judaism and Christianity to the Greek gods and beyond, are demonstrations of an innate human need to tell stories as a means of resolving conflicts.

At this point, a group of guests, visiting from the South, overhear Levis talking. They approach him to ask a question a lot of people ask at the Wilburton: “What is it with all the statues?”

Dozens of sculptures of different mythologies from all around the world are stationed throughout the grounds, creating a massive folk art installation. Abstract depictions of Abraham commingle with drawings of Pinocchio and the Egyptian Sphinx, and a large metal gate encircling the outdoor pavilion depicts various storybook images, including the Four Children of Passover. Some of these structures light up at night, while others are meant to be approached only from a certain angle; the collection is ever growing, and most are commissioned from local artists by Albert himself.

Albert lights up: explaining his sculptures is what he lives for. This, too, lets him circle back to his “Formal Theory”: the peculiar mixture of behavioral psychology, ancient mythologies, and cross-denominational religious fervor that he has rolled into an all-purpose explainer for how humans have sifted order from chaos throughout the grand expanse of time.

Smiling, he returns to his explanation of the Formal Theory. It will, he assures his growing audience, explain everything.

***

Albert Levis has lived many lives. He is 86, a Holocaust survivor, a psychiatrist, a real-estate investor, a businessman, a self-published author, a student of Jewish philosophy and Greek mythology, a possible future documentary star,and a ceaseless searcher of the human condition. He has channeled all of his passions and pursuits into a single-minded quest to explain the scientific process by which humanity turns traumatic, morally troubling experiences into stories: the Formal Theory.

Levis has spent the last several decades of his life honing this theory. He has pursued it through several volumes of textbooks (a seventh is on the way), workbooks and a board game called “Moral Monopoly.” He’s also sought to promote it via the purchase of an expanse of rural Vermont properties ranging from a plot of land purchased in 1972 that his son has turned into a farm, to an abandoned airport hangar he purchased last year; to the patronage of a Polish-American expressionist painter, to whom Levis has devoted the entirety of an art gallery he owns in downtown Manchester; and, most crucially, this inn, which he bought in 1987 intending to turn into a learning center for his theory.

Statues on the grounds of the Wilburton Inn at night, Manchester, Vermont, October 11, 2022. (Andrew Lapin/JTA)

“It’s not just that it’s been his life’s work, like somebody whose life’s work was to build a business,” Albert’s son Oliver told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency. “He really has been doing it to save the world.”

Touring the grounds of the inn on his golf cart, Levis proudly shows off the many features which, he hopes, will one day bring the world to a greater understanding of conflict resolution. Such tours can last for hours, and late into the night: no detail is too small for Albert to explain, and there is always some crucial piece of information just around the corner that you absolutely must hear.

“I love the guy intensely. And it doesn’t even matter to me that I don’t understand where he’s taking it,” Piper Strong, a sculpture artist who has made most of the metal works on the Wilburton grounds for Levis on commission, told JTA. “He wants to rebalance you, take you a little outside yourself and let you resettle in a whole new way.”

Strong has known the Levis family for nearly three decades. Their relationship began when she sold them her handmade Judaica for decorating the rooms at the inn, and evolved from there. Today she creates multiple pieces a year for Albert’s growing collection, all in some way matching his theory. These are done to his exact specifications, which Strong admits can feel “super fussy.”

She’s grateful for the work, and for their years of collaboration, but also admits to harboring a bit of jealousy toward the now-deceased surrealist painter Henry Gorski. Levis loved Gorski’s work so much, convinced its abstract visions of skulls, open mouths, and colliding athletes were the perfect visual representation of the Formal Theory, that he bought up most of the artist’s output and turned it into the singular focus of his Manchester gallery. Most of the illustrations in his books are Gorski’s paintings.

The Holocaust Memorial on the grounds of the Wilburton Inn, topped with a bust of Adolf Hitler behind bars, Manchester, Vermont, October 12, 2022. (Andrew Lapin/JTA)

There’s also a “Holocaust memorial” at the Wilburton: that’s Albert’s term for it, anyway. It consists of a group of sculptures even more abstract than the rest of the collection: a spiral staircase leading to nowhere; a purple dog frozen in mid-howl; a metal plate emblazoned with a swastika; a large Jenga-like tower of filing cabinets; a metal violin being plucked by disembodied fingers while half a face looks on.

“I have Hitler there, on top of a pyramid of safe deposit boxes, and behind furnaces,” he said. A bust of Mikhail Gorbachev, a personal hero of Levis, adorns the end of the memorial, with the Russian leader’s breakup of the Soviet Union positioned as the answer to the Holocaust. “Gorbachev was able to say, ‘Guys, open up and rethink or restructure your relationship,’” Levis explained.

Nearby, a sign reads, in small text, “A Holocaust Memorial As What We Learned From The 20th Century Is That Stories Mislead And That We Need to Shift Paradigms To What Is Universal In All Stories.” That’s just the header. The explanation goes on for several paragraphs of even smaller text that frame the Nazis’ Jewish extermination campaign as the end result of immoral storytelling. The plaque mentions Hitler’s “Mein Kampf,” which Levis said used pseudo-Darwinian influences in “justifying the extermination of the Jews as an inferior race,” and offers a take on “Jacob’s Ladder” (the staircase) as an example of positive conflict resolution.

Each one of these details has a particular meaning to Albert. Each one fits, ever so precisely, into the grand design of his Formal Theory. So too does the nondescript building on the grounds of the inn, which Albert calls the Museum of the Creative Process and where he leads group workshops on the topic.

“I’m very confident that what I have is a real scientific breakthrough,” he says.

Levis lives and entertains visitors in a carriage house just next door — alone, since the 2014 death of his wife Georgette, who oversaw the inn’s operations for decades while he pursued his theory (he recently has a new girlfriend). His children now run most of the day-to-day operations of the inn and farm, leaving Albert with more time to ponder and promote his theory, and try to figure out ways to get it in front of world leaders.

The Levis family, including Albert; his children Max, Oliver, Melissa and Tajlei; and grandchildren on the grounds of the Wilburton Inn, Manchester, Vermont. (Courtesy of the Wilburton Inn)

The kids help him with the theory, too: After all, they’ve been around it their whole lives. His daughter Melissa Levis, a musician, recalled her own bat mitzvah at the Wilburton, where instead of reading the Torah with a rabbi, she read “Wanderings” by Chaim Potok and wrote and performed a musical about the Bible informed by the theory.

“We wrote a song called ‘The Boogie Woogie Patriarchs,’ where we turned the story of the Four Patriarchs to the tune of ‘The Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy,’” she recalled. “Our mom wrote it and choreographed it, and we danced in the living room with our feather boas.”

Despite his cheery demeanor and lighthearted references to both his Greek and Jewish heritage, Albert wears his past with a heavy burden. More than 87% of Greece’s Jewish community was exterminated during the Holocaust, one of the highest figures of any nation; when Albert emerged from hiding after the war to attend high school and Athens College, he was one of the few Jews left in the country.

“It was an interesting kind of experience,” he recalled of his upbringing under a Christian name to evade the Nazis. In high school, Albert turned to fairy tales and other stories to anchor himself as he grappled with his own traumatic dissociation, finding particular comfort in Pinocchio, who, like Jonah in the Bible, is hidden from the world after he’s swallowed by a giant whale. Albert found himself asking fundamental questions about his own subsumed identity: “Who am I? What’s it all about?”

After earning his doctorate from the University of Zurich, writing plays on the side, he eventually came to the United States and completed a residency in psychiatry at Yale. He opened up a private practice in New Haven, Connecticut, before later moving to his current home of Manchester, an artsy resort town nestled in the Green Mountains.

Levis also married into one of the country’s most prominent Jewish families, the Wassersteins; his late wife Georgette was the sister of billionaire financier Bruce Wasserstein, corporate executive Sandra Meyer and Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Wendy Wasserstein, whose 1993 play “The Sisters Rosensweig” is itself inspired by the family’s many accomplishments.

In between some shrewd real-estate investments that enabled them to expand their footprint in Manchester, Albert and Georgette had four children. Each is brimming with accomplishments. There’s Melissa, a singer-songwriter who found success on the Long Island children’s circuit and would later become general manager of the inn, and Oliver, who took over the family farm, Earth Sky Time, and grew it into a regional sensation with live concerts and a bakery that folks rave about for miles around. Daughter Tajlei, a lawyer-turned-playwright, directs special events at the inn.

And son Max is a Harvard-educated psychiatrist who teaches at Dartmouth College and Bennington College, and has co-authored texts on the Formal Theory with Albert, lending the work a degree of institutional backing.

Max Levis on the grounds of the Levis family farm, Earth Sky Time, in Manchester, Vermont, October 12, 2022. (Andrew Lapin/JTA)

“The family is a pretty vivacious and dedicated core,” Max Levis told JTA, leaning on the front porch of his home, a tiny house the family built on Earth Sky Time’s property. “But there’s not going to be anybody like him, you know? And I’m aware of that. Albert is not just a Holocaust survivor. He’s a survivor of a world that just doesn’t exist anymore.”

“Do you know that Amichai poem about the tourist who comes to Jerusalem and is looking at this relic?” Max asked, referencing the Israeli poet Yehuda Amichai. “And Amichai concludes it by saying, ‘But look, beneath that relic, there’s a man coming back from market with his hands full of produce, who was alive.’ That’s what I’d say. My father is very much alive and has, if anything, his vigor: His love of life, of pushing forward, pushing humanity forward, is just his heartbeat.”

None of these markings of a life well lived were enough to satisfy Albert, who seems almost annoyed by the success each of his new ventures found independent of the Formal Theory. Sure, the inn and farm were booming, and his children were prospering — but meanwhile, his theory was languishing, at risk of being forgotten.

***

In its most basic, watered-down version, the Formal Theory holds that there is a six-step process by which “the mind transforms conflict to resolutions.”

As the individual’s mind proceeds along these steps — Stress, Response, Anxiety, Defense, Reversal, and Compromise — it is also oscillating between passive and active approaches to the outside world, and between what Levis refers to as “cooperation and antagonism.” How a person navigates these steps also determines which of four central personality types they belong to, similar to the Myers-Briggs indicator: Levis presents grids labeled in each corner with “Dominant,” “Submissive,” “Cooperative” and “Antagonistic.”

The playing field of Moral Monopoly, a board game designed by Albert Levis to teach the concepts of his Formal Theory of Behavior. Conflict resolution is divided into six steps (Stress, Response, Anxiety, Defense, Reversal, Compromise) and players make decisions on axes of Submissive-Dominant and Antagonistic-Cooperative. (Courtesy of Albert Levis)

These patterns of reasoning, Levis firmly believes, are identical to those that can be detected in the Greek creation myths, in all forms of religion, and in pretty much every other form of storytelling one can think of. His great quest is to link these two disciplines, the scientific study of the brain’s trauma response and the literary arts, and to insist that they are, in fact, one and the same.

There’s more, a lot more: enough to fill several volumes, and he has. But just communicating these basic points would, Levis believes, allow humanity to finally understand the patterns undergirding all of our decisions, both the uplifting and the destructive ones. And then, he believes, this knowledge would usher in world peace.

“The significance of my work is being able to see transformation, evolution, and justice as the natural end,” Levis said.

The act of storytelling, in Levis’ interpretation, is itself a moral act: the human brain creates morality when it sorts external events into the structure of a story. But it can also be an immoral act, if the story the human brain tells itself leads to the wrong conclusion. “When you write the story, it has a beginning, a middle and, at the end, happily ever after,” he explained. In his view, the chief lesson of history’s darkest chapters is that “stories mislead, and they’ll have to move to a new paradigm.”

It’s an idea that, Albert admits, was forged in the darkness of his experiences surviving the Holocaust. Decades after having hid from the Nazis in Greece, Levis — having become a respected psychologist — returned to Athens College with his new Formal Theory in tow, convinced it had the power to “heal the person and heal the world.”

“I felt returning to the school with a positive message was like being a Marathon runner telling the besieged Athenians: ‘We won,’’” he would later recount in a letter to the school.

He continued: “The journey reminded me why my life has been influenced by this period and why I have been so consistently seeking meaning. For me it has not been enough to memorialize the Holocaust. The question in my mind has been to identify: ‘What can we learn from history?’ Answering this question has shaped my career as a scientist.”

Albert Levis with a favorite painting of his, depicting him as one of the Ancient Greek scholars he idolizes, Manchester, Vermont, October 12, 2022. A modern painting by the artist Henry Gorski is mounted behind him. (Andrew Lapin/JTA)

While Albert claims to have an answer he will willingly share to all who ask, decoding it is an entirely different matter. Prior to my arrival at the Wilburton, he asked me to complete a psychological assessment he deemed the “Conflict Analysis Battery,” which he assured me would suss out exactly where I fit in the constellations of the Formal Theory.

I opted for the “short version,” which was advertised as taking 45 minutes. The first questions included self-assessments of phrases like “I expect too much of other people” and “I have difficulty accepting responsibility for the way I am.” Some verged into darker territory: “I occasionally get angry enough to want to kill.” An hour later, I was still answering these questions; I gave up and never finished.

Albert’s success rate with his approach seems to be largely anecdotal. Three decades ago, he said, he had tried out one of these tests on another Holocaust survivor, who visited his practice in an attempt to unpack her psychological scars.

Using his methods, Albert claimed, this patient uncovered what she said were long-repressed memories she never would have found via normal psychoanalytic methods, involving the childhood trauma of living under the Nazis and witnessing her Jewish mother die by suicide. It was all the evidence Albert needed to carry on, and to build on the battery with more and more behavioral tests. He has not committed any longitudinal, data-driven study of his work, and he has never applied for any funding for his research, which he says is “very time-consuming, and then you don’t even get it at the end.” In his view, the success stories are all the proof he needs.

Still, Levis assumes his theory will help save the world. It’s just a matter of getting the world to pay attention. He’s taken extreme steps in his efforts to do so: After 9/11, he drove his children to the New York State Capitol in Albany and tried to find the emergency response team “to try to get them to use his Formal Theory,” Oliver recalled.

Even Albert’s own Holocaust-survivor narrative, as compelling as it is, is mostly a vehicle for him to push his theory. He recently sat down for a series of interviews with the Shoah Foundation that lasted six days and said producers were interested in turning his testimony into its own documentary film. But, he said, he was unhappy with the idea: “I wanted to create something that is more educational than dramatic.”

After Georgette’s death, Melissa, Max and Tajlei took over the Wilburton, channeling her flair for performance into a series of year-round events. Melissa also filmed Albert for what is likely his biggest public exposure to date: a brief YouTube video called “Psychiatrist Dr. Albert Levis analyzes Trump,” featuring Albert reciting a minute-long diagnosis of the former president (“a dominant antagonistic person who has absolutely no end to his dominance”) that has been viewed by over 100,000 people since it was uploaded in 2021.

Albert laughs at the Trump video today, though he’s also quick to bring up the man’s name in discussions of his theory — as in, “If only Trump had any little bit of sense!” Recently, he said, he has been studying the speech patterns of different politicians to determine the qualities that make them “submissive” and “dominant”: on one end of the spectrum is Lincoln, Gandhi and Gorbachev, and on the other is Hitler, Putin and Trump.

The specter of Trump seems to be, in some ways, a principal motivator for his work these days, as is the mere fact that war and evil still exist in the world today. “He feels these things,” Max said. “I remember when the war with Ukraine started, like how personally he took that as his own failure.”

***

A year later, with the world fully immersed in the Israel-Hamas war, Levis seemed by contrast almost cheerful about recent progress on his theory.

Reached by phone last month in San Juan, where he was vacationing with his children and grandchildren, Levis excitedly described his recent ventures into artificial intelligence and ChatGPT. He hopes to use the software to chart the “modalities” in all manner of stories, finding the commonalities in their character arcs that will provide a wealth of data for his theory.

To Albert, the Oct. 7 attack and Israel’s response in the Gaza Strip are yet more symptoms of his underlying concern with humanity: its reliance on stories (in this case, religion) to solve problems.

“I think it’s only a question of time before my ideas are being recognized as meaningful, before people destroy each other,” he said. “I’d like to think at some point I’ll be on talk shows. I’ll get a following.”

He has also taken his theory into the classroom, with Max and Melissa’s help. The three of them recently paid a visit to a psychology class Max Levis was teaching at Bennington, where Melissa taught the students a song-and-dance routine that mapped up with the Formal Theory. The students loved it, and Albert was excitedly poring over their effusive class evaluations. “It’s very gratifying,” he said.

“He uses the metaphor of Odysseus getting to Ithaca a lot,” Melissa said, reflecting on her father’s journey. “And if ‘Ithaca’ is ‘becoming recognized in mainstream psychology,’ if that’s the point… our journey to Ithaca has been magical.”

While Albert chased his theory, he — almost by accident — instead created a more traditional kind of story: one about a Jewish family’s success in the wake of a genocide. The Wilburton Inn, originally purchased as a retreat center for the theory, has blossomed into one of the region’s top-rated lodgings. Earth Sky Time Farm, meant to help financially support research into the theory, is now a widely respected model for sustainable farming and a regional concert and festival destination. The Levis family as a whole is charismatic, well-educated, generous with their time and wisdom, and close to their father — physically, too: Melissa spends much of her time at the inn, while Oliver and Max literally live across the street. You could say that the family’s collective mind, in accordance with Albert’s theory, transformed conflict into resolution.

Undaunted, Levis hopes to turn the long-abandoned airport he just bought into yet another showcase for his theory, this one unencumbered by the economic constraints of running a farm or an inn. He has once again commissioned Strong to design metalworks for the site, although recent flooding in the region has slowed down his efforts to develop the property. Still, in his late eighties, he presses on. The airport, Levis said, will be just for him.

On Earth Sky Time Farm, the Levis family is focused on smaller pleasures. In the fall, Albert’s grandchildren run and play across grass that is still slightly trampled from the end of the farm’s concert season. The bakery is churning out bread, and the harvest’s leftover vegetables find their way to their sukkah table as a stew.

“To anybody else that would be enough, you know?” Oliver would later reflect on this idyllic scene. “That would be success, by most measures.”

Yet around the table, the conversation has once again turned to Albert’s theory. The patriarch tells the group that he sees himself as working in the tradition of the great philosophers, like Maimonides. His family gently chides him. Maimonides, they tell him, was persecuted in his time.

Back at the inn, Albert looks out on the Green Mountains and sips a beer. He could be out promoting his theory even more aggressively, he surmises. But, he laughs, “I’m having too much fun.”

—

The post A Greek Holocaust survivor in Vermont knows how to save humanity. He just needs us to listen. appeared first on Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

RSS

After False Dawns, Gazans Hope Trump Will Force End to Two-Year-Old War

Palestinians walk past a residential building destroyed in previous Israeli strikes, after Hamas agreed to release hostages and accept some other terms in a US plan to end the war, in Nuseirat, central Gaza Strip October 4, 2025. Photo: REUTERS/Mahmoud Issa

Exhausted Palestinians in Gaza clung to hopes on Saturday that US President Donald Trump would keep up pressure on Israel to end a two-year-old war that has killed tens of thousands and displaced the entire population of more than two million.

Hamas’ declaration that it was ready to hand over hostages and accept some terms of Trump’s plan to end the conflict while calling for more talks on several key issues was greeted with relief in the enclave, where most homes are now in ruins.

“It’s happy news, it saves those who are still alive,” said 32-year-old Saoud Qarneyta, reacting to Hamas’ response and Trump’s intervention. “This is enough. Houses have been damaged, everything has been damaged, what is left? Nothing.”

GAZAN RESIDENT HOPES ‘WE WILL BE DONE WITH WARS’

Ismail Zayda, 40, a father of three, displaced from a suburb in northern Gaza City where Israel launched a full-scale ground operation last month, said: “We want President Trump to keep pushing for an end to the war, if this chance is lost, it means that Gaza City will be destroyed by Israel and we might not survive.

“Enough, two years of bombardment, death and starvation. Enough,” he told Reuters on a social media chat.

“God willing this will be the last war. We will hopefully be done with the wars,” said 59-year-old Ali Ahmad, speaking in one of the tented camps where most Palestinians now live.

“We urge all sides not to backtrack. Every day of delay costs lives in Gaza, it is not just time wasted, lives get wasted too,” said Tamer Al-Burai, a Gaza City businessman displaced with members of his family in central Gaza Strip.

After two previous ceasefires — one near the start of the war and another earlier this year — lasted only a few weeks, he said; “I am very optimistic this time, maybe Trump’s seeking to be remembered as a man of peace, will bring us real peace this time.”

RESIDENT WORRIES THAT NETANYAHU WILL ‘SABOTAGE’ DEAL

Some voiced hopes of returning to their homes, but the Israeli military issued a fresh warning to Gazans on Saturday to stay out of Gaza City, describing it as a “dangerous combat zone.”

Gazans have faced previous false dawns during the past two years, when Trump and others declared at several points during on-off negotiations between Hamas, Israel and Arab and US mediators that a deal was close, only for war to rage on.

“Will it happen? Can we trust Trump? Maybe we trust Trump, but will Netanyahu abide this time? He has always sabotaged everything and continued the war. I hope he ends it now,” said Aya, 31, who was displaced with her family to Deir Al-Balah in the central Gaza Strip.

She added: “Maybe there is a chance the war ends at October 7, two years after it began.”

RSS

Mass Rally in Rome on Fourth Day of Italy’s Pro-Palestinian Protests

A Pro-Palestinian demonstrator waves a Palestinian flag during a national protest for Gaza in Rome, Italy, October 4, 2025. Photo: REUTERS/Claudia Greco

Large crowds assembled in central Rome on Saturday for the fourth straight day of protests in Italy since Israel intercepted an international flotilla trying to deliver aid to Gaza, and detained its activists.

People holding banners and Palestinian flags, chanting “Free Palestine” and other slogans, filed past the Colosseum, taking part in a march that organizers hoped would attract at least 1 million people.

“I’m here with a lot of other friends because I think it is important for us all to mobilize individually,” Francesco Galtieri, a 65-year-old musician from Rome, said. “If we don’t all mobilize, then nothing will change.”

Since Israel started blocking the flotilla late on Wednesday, protests have sprung up across Europe and in other parts of the world, but in Italy they have been a daily occurrence, in multiple cities.

On Friday, unions called a general strike in support of the flotilla, with demonstrations across the country that attracted more than 2 million, according to organizers. The interior ministry estimated attendance at around 400,000.

Italy’s right-wing government has been critical of the protests, with Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni suggesting that people would skip work for Gaza just as an excuse for a longer weekend break.

On Saturday, Meloni blamed protesters for insulting graffiti that appeared on a statue of the late Pope John Paul II outside Rome’s main train station, where Pro-Palestinian groups have been holding a protest picket.

“They say they are taking to the streets for peace, but then they insult the memory of a man who was a true defender and builder of peace. A shameful act committed by people blinded by ideology,” she said in a statement.

Israel launched its Gaza offensive after Hamas terrorists staged a cross border attack on October 7, 2023, killing some 1,200 people and taking 251 people hostage.

RSS

Hamas Says It Agrees to Release All Israeli Hostages Under Trump Gaza Plan

Smoke rises during an Israeli military operation in Gaza City, as seen from the central Gaza Strip, October 2, 2025. Photo: REUTERS/Dawoud Abu Alkas

Hamas said on Friday it had agreed to release all Israeli hostages, alive or dead, under the terms of US President Donald Trump’s Gaza proposal, and signaled readiness to immediately enter mediated negotiations to discuss the details.