RSS

‘Golda’ focuses on a few grim weeks in the life of Israel’s first female prime minister. A biographer wants you to see the bigger picture.

(JTA) — “Golda,” the new biopic starring Helen Mirren as Israel’s first (and so far only) female prime minister, focuses on the few terrible weeks late in her life that would in some ways seal Golda Meir’s legacy. On Yom Kippur 1973, Egypt and Syria led a sneak attack on Israel that, in its stealth and fury, erased the euphoria that followed Israel’s lightning victory six years earlier in the Six-Day War.

The public blamed Meir for Israel’s lack of preparation; she resigned in 1974 and her reputation, particularly in Israel, has never really recovered.

For Meir’s defenders, her legacy has often been obscured by misogyny and condescension. Biographers like Francine Klagsbrun, in 2017’s “Lioness,” and Deborah Lipstadt, whose “Golda Meir: Israel’s Matriarch” was published this month, argue for a fuller, more generous assessment of Meir. They recall a Zionist pioneer, born in present-day Ukraine in 1898 and raised in Milwaukee, who helped shape public opinion about the nascent Jewish state in the United States and ignited American Jewish fundraising for its cause; a Labor Zionist activist who helped establish the Israeli welfare state that sustained the country and its waves of immigrants through the 1980s, and a foreign minister who, over a decade, forged important alliances with the French, the United Nations and, most importantly, the United States.

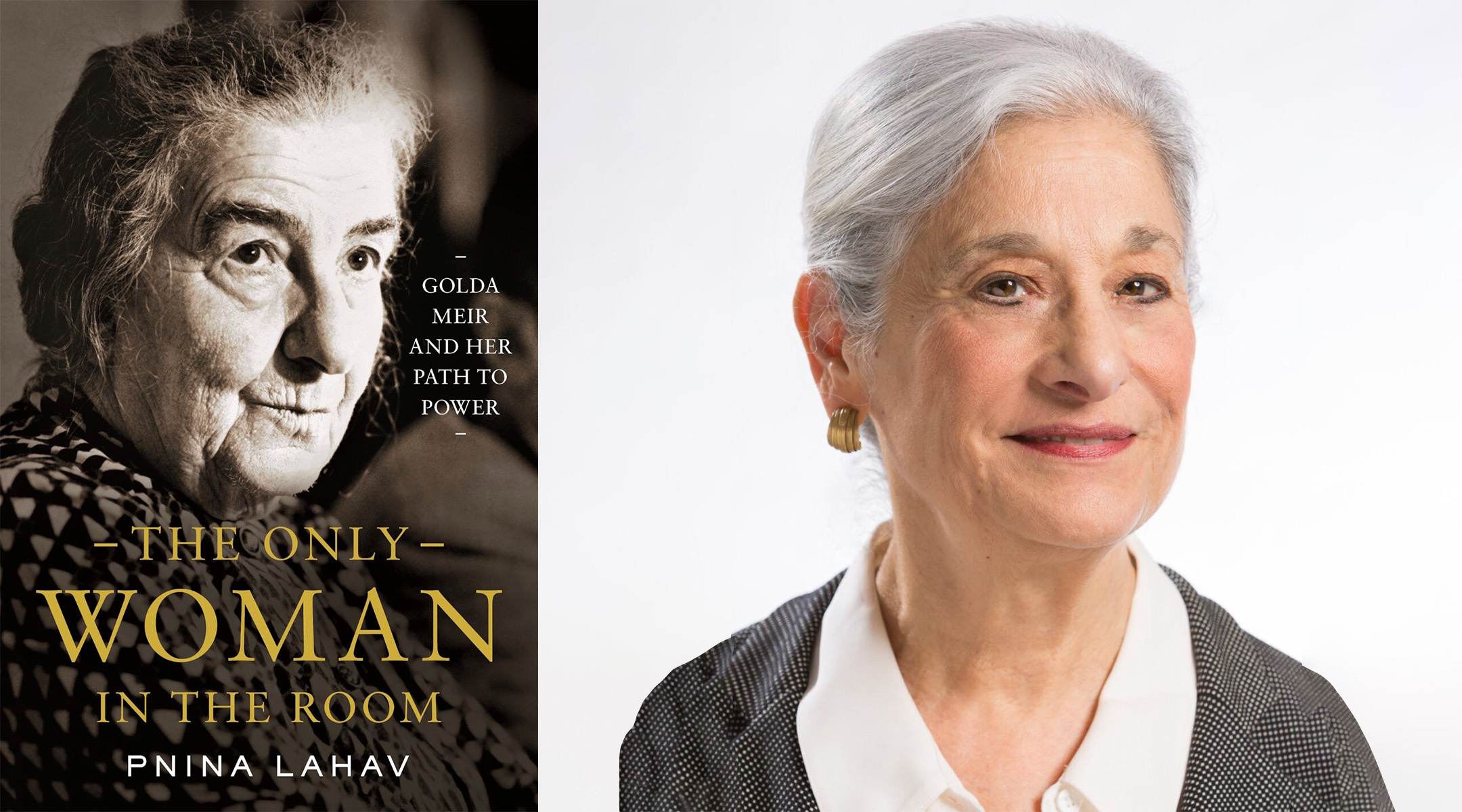

In “The Only Woman in the Room: Golda Meir and Her Path to Power,” which came out late last year, Pnina Lahav picks up on these themes and develops another: How Meir, adamant in not calling herself a feminist, nevertheless refused to be defined by the traditional roles set out for her and instead forged a path for other women in politics.

Lahav, born in Israel, is an emerita professor of law and a member of the Elie Wiesel Center for Judaic Studies at Boston University. We spoke this week about the ways Meir has been underestimated, how she defied the Jewish grandmother stereotype and how a flawed leader can also be considered a great one.

Our conversation was edited for length and clarity.

Your book asks us to consider the ways Golda Meir succeeded as a woman in a man’s world, but also asks that we judge her by the standards of Israel’s other male leaders, both in her accomplishments and in her flaws. What did you discover in your research that may have changed your perception, or the public’s perception, of her as a leader?

As I learned about her decision-making, the way she conducted foreign affairs, I came to respect her more and more. I did not expect to see a very savvy, very experienced and caring person as I saw at the end.

I wanted to give [the book] as a gift to the Israeli people, particularly to Israeli women, to say to them that we also have great leaders. It’s not only Moshe Dayan and David Ben-Gurion. Golda was a great leader. She understood exactly what was going on. She was capable of making important policy. She had a very good relationship with the American administration, and we should be very proud of her rather than putting her down. Israelis have a tendency to look down and underestimate her as someone who was not really up to the job. I think it’s a big, big mistake.

Before we look at her political career, I wanted to step back. She grew up in Milwaukee, but was born in Kyiv at a time when Jews were experiencing persecution and pogroms. How much did that shape who she became?

I think very little. Before coming to America, she was a little girl. She was not subjected to a pogrom. Let’s not forget, she used the pogrom as a PR piece. She used it to extol the significance of Zionism: “Outside of Israel we are subjected to pogroms, inside we are protected.”

That was a pitch she used effectively in the 1930s, before she became a central figure in Israeli politics. After moving to Palestine in 1921, she would regularly travel back to the States to fundraise and promote the Labor Zionist cause here, to groups like Pioneer Women and other Jewish groups. To what degree did she create the image of Israel in the minds of American Jews?

She’s the one who laid the foundation for a very strong relationship with the American government and the American people. One of the reasons for this was that she was an American. She knew how to speak to them. It’s not only the language but the body language, the culture. Other leaders who grew up in Germany, or Holland, or even in England did not understand the American instinct in the same way. She always kept her Midwestern accent. And that was very important because it communicated an affinity with the United States.

Golda Meir was indeed the “only woman in the room” at the first session of Israel’s third government, in 1951. Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion chairs the meeting. (David Eldan, National Photo Collection of Israel, Goverment Press Office)

A lot of the American Jewish establishment was not really keen on Zionism before Israel’s establishment. But she was speaking directly to working class Jews who came to view it as a place, if they weren’t going to move there, that they wanted to support and build.

For many of them it was a haven — if something happened, God forbid, we have a place to protect us. She knew how to play on this.

Golda graduated from a school for teachers in Milwaukee, but all of her education in statecraft and foreign policy was on-the-job training. What were her strengths in becoming a spokesperson and diplomat?

As I did the research, it was interesting to me how attentive she was to other views. She was always willing to consult, always willing to listen. She didn’t always accept your advice, but she always took it into consideration. I thought that was a very important thing.

I would also say that the men that she befriended, such as David Remez [Israel’s first Minister of Transportation], who was her lover for many years, also influenced her in terms of foreign affairs. They were very, very experienced and educated people. And she relied on them to learn and to expand her views. She knew how to choose her friends, like Zalman Shazar, who eventually became president of Israel. These were the people that she socialized with and associated with. She didn’t go to school. So she basically absorbed information and analysis from the people that she was socializing with.

Golda was 70 when she became prime minister in 1969, and 75 when she resigned in the wake of the near-debacle of the Yom Kippur War, which in some ways became her legacy. But you, like others, argue for a more complete portrait of what she accomplished as a leader before and after the establishment of the state.

I’m afraid many people today in Israel forget Golda, and many people remember Golda negatively, because of the Yom Kippur War, which they tend to blame her for. It’s not entirely fair. There was a lot of bias against Golda over time, and the reason is basically misogyny: People did not like the idea that they had a female leader, especially in wartime. She also had a lot of enemies in Israeli politics. So people like, for example, Shimon Peres — they did not like her. They were spreading a lot of information about her that was very negative. She had to fight a lot of negative press. I remember myself as a student, that we didn’t really think much of her. It’s only slowly that a younger generation like ours began to value her contributions.

But at the same time, if you look at public opinion polls at the time, you see that the Israeli public was very supportive and very, very positive about her leadership.

Golda’s greatest contribution was in foreign affairs. She came to fame in the 1950s as minister of foreign affairs, and she gained a lot of experience, which she then put to good use later as a prime minister. People saw that she had a very good relationship with the American administration, which was the thing that really counted in Israel. She knew the Nixon administration very well. She had a very good relationship with [then Secretary of State] Henry Kissinger. They did not always see eye to eye, but they had good relationships. They could speak to each other. They would try to persuade each other.

As you said, negative perceptions of Meir came from the Yom Kippur War, when Israel appeared unprepared for the attack by Arab armies and lost not only 2,500 soldiers but its own sense of security. What led to the negative impressions of her during and after the war? Did you find anything that showed that she may not have deserved that kind of criticism?

First of all, before the war, Israelis were on top of the world, and she essentially made the same miscalculation. She announced many, many times before the war, when elections were being held at the same time, that “we never had it so good.” And suddenly, we found ourselves attacked by Egypt and Syria, and the feeling that we were going to lose that war was very strong, very deep. The change from the sense of security and the confidence to the surprise of the war was great. So she became the scapegoat. People will simply blame the leader when things don’t go well.

Still, she successfully made the case to the Nixon administration that it had to resupply Israel with weapons, which helped turn the fight against the Arab states.

Golda had great persuasive powers. Even if you disagreed with her, you’d slowly begin to see her point of view much more positively.

What do people get wrong about her, either positively or negatively? I am thinking how she is sometimes portrayed as sort of a quintessential Jewish grandmother, but was in fact was a really tough and well-informed political operative.

It’s a tricky question, because for young people, the Golda that she was after the war was not the same Golda that she was before. So people look negatively at her after the war and blame her for a lot of things that they actually should have blamed themselves for.

Such as?

Most Israelis made it very clear after 1967 that they didn’t want to return any of the territories seized in the Six-Day War [which included the West Bank, the Sinai peninsula and the Golan Heights]. They didn’t want to return any of it, and they were not receptive to compromises. They felt the Arab side should compromise. So they were very surprised when they launched this war against them. And they were also very surprised to see that the United States was not 100% behind Israel and was willing to be more objective. And then they looked for somebody to blame, and blamed her for not supporting a compromise with [Egyptian president Anwar] Sadat [before the war]. But public opinion, by and large, didn’t want it. They were not interested in giving up anything.

She also said that we could overcome anything, and one of the reasons for that is that her military advisors were promising her that everything was going to be okay and that we could always win the war.

Golda Meir meets with Israeli Defense Minister Moshe Dayan and troops on the Golan Heights during the Yom Kippur War, Oct. 21, 1973. (Ron Frenkel/GPO/Getty Images)

Did she have a blind spot toward the Palestinians? She gave the famous interview in 1969 when she said, “There was no such thing as Palestinians,” meaning there was no independent Palestinian Arab state, entity or identity prior to the creation of Israel.

I wouldn’t call it a blindspot. I think it was an effort on her part to cater to the trend in public opinion. The public opinion at the time was developing the view that there is no such thing as a Palestinian people. And she thought it was useful for Israeli foreign affairs. But if you look at her history, she knew very well that there was a Palestinian people. When she came to Israel, she saw a Palestinian people but she slowly went over to this other view. And the feeling that she also shared was that, “we don’t want to compromise.” It was a feeling that Israel fought a successful war [in 1967] and we are entitled now to reap the fruit of our efforts.

Was she especially sensitive to public opinion?

She was the kind of leader who followed the crowd, or public opinion. And so she felt that if that’s what people want, and if she also felt this way, that therefore that was the way we should develop our policy. For a contrast, if you read [Israeli diplomat] Abba Eban’s memoirs, you see that he wanted to compromise, he wanted to reach out to the Arab side and she basically marginalized him. She didn’t want to hear what he had to say.

And so from this perspective, you can say she was not a good leader. Because she did not foresee what was coming. It’s tragic.

Do you have any personal memories of her?

I’m 77. I was a student when she was prime minister, and a child when she was Minister of Foreign Affairs. When I saw her I was at the margins of a crowd, and I was just a lowly 20-year-old.

I do remember watching her once in conversation. I was impressed by the way that she was in control of the conversation. But I don’t want to claim that I knew her or that I have something more valuable to say than that.

There’s a lot of controversy about her views on feminism. Many feminists were and are disappointed that she never could bring herself to endorse the movement despite her own accomplishments.

Whether she liked it or not, she was a feminist. She believed that women should have the power to conduct policy, and to go up the ladder in politics. She wanted to have a life outside of the home. And she said she needed to work and she needed to make a difference.

She was a feminist in action: an ambitious woman who can learn the secrets of the trade and go up the ladder all the way to the prime ministership. But she did not understand the value of feminism. She was afraid of it and the reason I think she was afraid of it is that Israelis were very much against feminism at the time, which is due primarily to militarism. Militarism was very strong in Israel at the time and Israelis admired the strong leaders, you know, the generals in the field.

When you think about Israel now, with a far-right government, with the public upheaval over attempts by the current prime minister to overhaul the judiciary, what lessons from Golda’s life might apply at the present moment?

I believe the word “hubris” should come into the picture. At the time of the Yom Kippur War, we were full of hubris. We were sure that nothing could vanquish us or bring us to do something that we didn’t want to do. And I think we may be in the same situation today. And that is always the problem. We’re fairly strong, with a strong army, the United States is on our side, and we say to ourselves, “we can do anything,” but there is no situation in which you can do anything. And the truth of the matter is you need to listen to the other side, understand where the compromise is, and give something back.

—

The post ‘Golda’ focuses on a few grim weeks in the life of Israel’s first female prime minister. A biographer wants you to see the bigger picture. appeared first on Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

RSS

Hamas Says No Interim Hostage Deal Possible Without Work Toward Permanent Ceasefire

Explosions send smoke into the air in Gaza, as seen from the Israeli side of the border, July 17, 2025. Photo: REUTERS/Amir Cohen

The spokesperson for Hamas’s armed wing said on Friday that while the Palestinian terrorist group favors reaching an interim truce in the Gaza war, if such an agreement is not reached in current negotiations it could revert to insisting on a full package deal to end the conflict.

Hamas has previously offered to release all the hostages held in Gaza and conclude a permanent ceasefire agreement, and Israel has refused, Abu Ubaida added in a televised speech.

Arab mediators Qatar and Egypt, backed by the United States, have hosted more than 10 days of talks on a US-backed proposal for a 60-day truce in the war.

Israeli officials were not immediately available for comment on the eve of the Jewish Sabbath.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s office said in a statement on a call he had with Pope Leo on Friday that Israel‘s efforts to secure a hostage release deal and 60-day ceasefire “have so far not been reciprocated by Hamas.”

As part of the potential deal, 10 hostages held in Gaza would be returned along with the bodies of 18 others, spread out over 60 days. In exchange, Israel would release a number of detained Palestinians.

“If the enemy remains obstinate and evades this round as it has done every time before, we cannot guarantee a return to partial deals or the proposal of the 10 captives,” said Abu Ubaida.

Disputes remain over maps of Israeli army withdrawals, aid delivery mechanisms into Gaza, and guarantees that any eventual truce would lead to ending the war, said two Hamas officials who spoke to Reuters on Friday.

The officials said the talks have not reached a breakthrough on the issues under discussion.

Hamas says any agreement must lead to ending the war, while Netanyahu says the war will only end once Hamas is disarmed and its leaders expelled from Gaza.

Almost 1,650 Israelis and foreign nationals have been killed as a result of the conflict, including 1,200 killed in the Oct. 7, 2023, Hamas attack on southern Israel, according to Israeli tallies. Over 250 hostages were kidnapped during Hamas’s Oct. 7 onslaught.

Israel responded with an ongoing military campaign aimed at freeing the hostages and dismantling Hamas’s military and governing capabilities in neighboring Gaza.

The post Hamas Says No Interim Hostage Deal Possible Without Work Toward Permanent Ceasefire first appeared on Algemeiner.com.

RSS

Iran Marks 31st Anniversary of AMIA Bombing by Slamming Argentina’s ‘Baseless’ Accusations, Blaming Israel

People hold images of the victims of the 1994 bombing attack on the Argentine Israeli Mutual Association (AMIA) community center, marking the 30th anniversary of the attack, in Buenos Aires, Argentina, July 18, 2024. Photo: REUTERS/Irina Dambrauskas

Iran on Friday marked the 31st anniversary of the 1994 bombing of the Argentine Israelite Mutual Association (AMIA) Jewish community center in Buenos Aires by slamming Argentina for what it called “baseless” accusations over Tehran’s alleged role in the terrorist attack and accusing Israel of politicizing the atrocity to influence the investigation and judicial process.

The Iranian Foreign Ministry issued a statement on the anniversary of Argentina’s deadliest terrorist attack, which killed 85 people and wounded more than 300.

“While completely rejecting the accusations against Iranian citizens, the Islamic Republic of Iran condemns attempts by certain Argentine factions to pressure the judiciary into issuing baseless charges and politically motivated rulings,” the statement read.

“Reaffirming that the charges against its citizens are unfounded, the Islamic Republic of Iran insists on restoring their reputation and calls for an end to this staged legal proceeding,” it continued.

Last month, a federal judge in Argentina ordered the trial in absentia of 10 Iranian and Lebanese nationals suspected of orchestrating the attack in Buenos Aires.

The ten suspects set to stand trial include former Iranian and Lebanese ministers and diplomats, all of whom are subject to international arrest warrants issued by Argentina for their alleged roles in the terrorist attack.

In its statement on Friday, Iran also accused Israel of influencing the investigation to advance a political campaign against the Islamist regime in Tehran, claiming the case has been used to serve Israeli interests and hinder efforts to uncover the truth.

“From the outset, elements and entities linked to the Zionist regime [Israel] exploited this suspicious explosion, pushing the investigation down a false and misleading path, among whose consequences was to disrupt the long‑standing relations between the people of Iran and Argentina,” the Iranian Foreign Ministry said.

“Clear, undeniable evidence now shows the Zionist regime and its affiliates exerting influence on the Argentine judiciary to frame Iranian nationals,” the statement continued.

In April, lead prosecutor Sebastián Basso — who took over the case after the 2015 murder of his predecessor, Alberto Nisman — requested that federal Judge Daniel Rafecas issue national and international arrest warrants for Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei over his alleged involvement in the attack.

Since 2006, Argentine authorities have sought the arrest of eight Iranians — including former president Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, who died in 2017 — yet more than three decades after the deadly bombing, all suspects remain still at large.

In a post on X, the Delegation of Argentine Israelite Associations (DAIA), the country’s Jewish umbrella organization, released a statement commemorating the 31st anniversary of the bombing.

“It was a brutal attack on Argentina, its democracy, and its rule of law,” the group said. “At DAIA, we continue to demand truth and justice — because impunity is painful, and memory is a commitment to both the present and the future.”

31 años del atentado a la AMIA – DAIA. 31 años sin justicia.

El 18 de julio de 1994, un atentado terrorista dejó 85 personas muertas y más de 300 heridas. Fue un ataque brutal contra la Argentina, su democracia y su Estado de derecho.

Desde la DAIA, seguimos exigiendo verdad y… pic.twitter.com/kV2ReGNTIk

— DAIA (@DAIAArgentina) July 18, 2025

Despite Argentina’s longstanding belief that Lebanon’s Shiite Hezbollah terrorist group carried out the devastating attack at Iran’s request, the 1994 bombing has never been claimed or officially solved.

Meanwhile, Tehran has consistently denied any involvement and refused to arrest or extradite any suspects.

To this day, the decades-long investigation into the terrorist attack has been plagued by allegations of witness tampering, evidence manipulation, cover-ups, and annulled trials.

In 2006, former prosecutor Nisman formally charged Iran for orchestrating the attack and Hezbollah for carrying it out.

Nine years later, he accused former Argentine President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner — currently under house arrest on corruption charges — of attempting to cover up the crime and block efforts to extradite the suspects behind the AMIA atrocity in return for Iranian oil.

Nisman was killed later that year, and to this day, both his case and murder remain unresolved and under ongoing investigation.

The alleged cover-up was reportedly formalized through the memorandum of understanding signed in 2013 between Kirchner’s government and Iranian authorities, with the stated goal of cooperating to investigate the AMIA bombing.

The post Iran Marks 31st Anniversary of AMIA Bombing by Slamming Argentina’s ‘Baseless’ Accusations, Blaming Israel first appeared on Algemeiner.com.

RSS

Jordan Reveals Muslim Brotherhood Operating Vast Illegal Funding Network Tied to Gaza Donations, Political Campaigns

Murad Adailah, the head of Jordan’s Muslim Brotherhood, attends an interview with Reuters in Amman, Jordan, Sept. 7, 2024. Photo: REUTERS/Jehad Shelbak

The Muslim Brotherhood, one of the Arab world’s oldest and most influential Islamist movements, has been implicated in a wide-ranging network of illegal financial activities in Jordan and abroad, according to a new investigative report.

Investigations conducted by Jordanian authorities — along with evidence gathered from seized materials — revealed that the Muslim Brotherhood raised tens of millions of Jordanian dinars through various illegal activities, the Jordan news agency (Petra) reported this week.

With operations intensifying over the past eight years, the report showed that the group’s complex financial network was funded through various sources, including illegal donations, profits from investments in Jordan and abroad, and monthly fees paid by members inside and outside the country.

The report also indicated that the Muslim Brotherhood has taken advantage of the war in Gaza to raise donations illegally.

Out of all donations meant for Gaza, the group provided no information on where the funds came from, how much was collected, or how they were distributed, and failed to work with any international or relief organizations to manage the transfers properly.

Rather, the investigations revealed that the Islamist network used illicit financial mechanisms to transfer funds abroad.

According to Jordanian authorities, the group gathered more than JD 30 million (around $42 million) over recent years.

With funds transferred to several Arab, regional, and foreign countries, part of the money was allegedly used to finance domestic political campaigns in 2024, as well as illegal activities and cells.

In April, Jordan outlawed the Muslim Brotherhood, the country’s most vocal opposition group, and confiscated its assets after members of the Islamist movement were found to be linked to a sabotage plot.

The movement’s political arm in Jordan, the Islamic Action Front, became the largest political grouping in parliament after elections last September, although most seats are still held by supporters of the government.

Opponents of the group, which is banned in most Arab countries, label it a terrorist organization. However, the movement claims it renounced violence decades ago and now promotes its Islamist agenda through peaceful means.

The post Jordan Reveals Muslim Brotherhood Operating Vast Illegal Funding Network Tied to Gaza Donations, Political Campaigns first appeared on Algemeiner.com.