RSS

When Dr. Martin Luther King and Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel taught my dad to pray with his feet

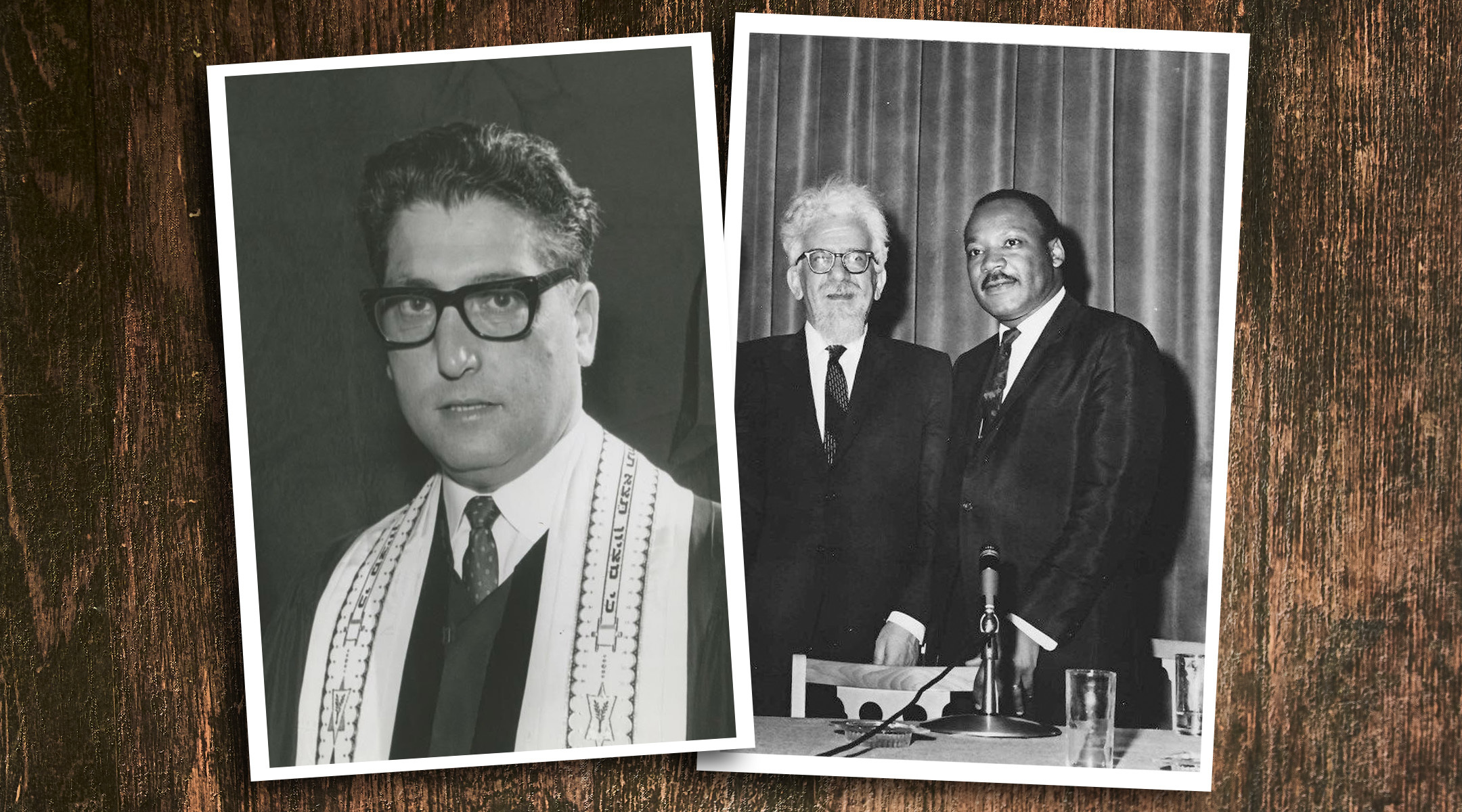

(JTA) — Abraham Joshua Heschel, whose 50th yahrzeit we marked this past year, was for almost 30 years a member of the faculty at The Jewish Theological Seminary, which I lead. There he inspired many to incorporate traditional Jewish learning, observance and values into their modern lives.

But he also preached the importance of emulating the biblical prophets, who in his view, were not merely entranced conduits of God’s word but rather fully aware critics of the social injustices of their days. He believed that the immanent presence of God in the world required humans to fight injustice — as he did in his public advocacy for civil rights and in his fast friendship with Dr. Martin Luther King. Through his teaching, writing and personal example, Heschel inspired thousands to deepen their Jewish commitments and actively advance social justice causes.

But how did that inspiration actually play out? Thanks to my father, Rabbi Mordecai Rubin, I am better able to answer that question. I knew that my father had studied with Rabbi Heschel at the JTS Rabbinical School, and I remember my father attending the March on Washington in August 1963 and being awed by the experience. He woke up in the dark to board a chartered bus by 5 a.m along with other Jewish professionals and some lay leaders. He recalled that only as he saw the hundreds of other buses on the highway en route to the rally did he realize how important the day would be.

A young child at the time, I could not fully appreciate the historic importance of the march — its size, the presence of so many clergy including rabbis, the impact of Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech. I also did not comprehend how courageous it was for my father to attend that march and then to speak about it to his congregation. But as an American Jewish historian, I know that — contrary to conventional retrospective wisdom — most American Jews at the time were reluctant to get involved in the Civil Rights Movement. Less than 20 years after the Shoah, these Jews, many of whom were children of immigrants who fled Tsarist Russia, hungered for acceptance as one of the three primary American religious groups. Most American Jews feared that their own security would be threatened if they rocked the boat by championing civil rights.

So why did he (and perhaps others like him) decide to attend the March on Washington? I got a glimpse into his thinking when I recently found the Rosh Hashanah sermon that he delivered to his congregation, the Wantagh Jewish Center, in Wantagh, New York, in September 1963, a month after the march.

In the mood of soul searching and introspections — so dominant on these High Holy Days — I should like to share these thoughts with you…

It was the first time that I had participated in a march and with each passing day — awareness swells within me of something special and unique that transformed and perhaps even reformed me…

I had many moments of doubt instead of standing up to be counted in the roll call of human conscience. As a matter of fact, I must confess that my decision to go was not without questions of doubt…. But there comes a moment of truth for every human being. And it came [to me] as I began to reflect…Why was I so angry at the non-Jewish world for remaining deaf to the pleas of our brethren in Nazi Germany 20 years ago? Why didn’t we or our Jewish leaders march on Washington when our own flesh and blood was being led to the crematoria…

We have learned to love life and to enjoy it – But we have forgotten how to live — how to sacrifice, and how to give of ourselves….and even the one great source of our idealism – Religion, our Judaic faith, instead of remaining an institution of protest against the comfortable self-centered, self-satisfying way of life, has more often than not, been content to be engulfed by it and a symbol of this evil…

I hear the echoes of Rabbi Heschel in my father’s words. His own passion about the Jewish imperative to speak out against injustice is palpable. But my father knew his congregants might balk at this message. He understood that to be heard, he had to speak not as a prophet but as a fellow suburban postwar American Jew. He needed his congregants to understand that he identified with their fears, struggles and hopes. Only then could he gently encourage them to reexamine their assumptions and choices. Only then could he inspire them to live up to their highest religious ideals.

Dr. King shone a moral light on the challenges and articulated the goals of the Civil Rights Movement that he led. This is one of the many reasons JTS bestowed upon him an honorary degree in 1964. In 1968, Heschel introduced King at the Rabbinical Assembly convention at the Concord Hotel in the Catskills, where he inspired over a thousand rabbis and spouses (including my parents) at what turned out to be one of his last addresses before his assassination. But the leadership challenge that my dad, and I’m sure many others, faced was more intimate and precarious in scale. For one thing, my father wasn’t employed by a social justice organization and didn’t have life tenure. To effect change over time, he’d need to motivate his congregants while continuing to secure his longevity in the congregation.

And he did just that, remaining in that congregation until his death 30 years later, deepening the Jewish values, commitments, and socially conscious engagement of many thousands of congregants over the decades.

Too often we see “leadership” discussed as if it were quantifiable and replicable. But it is often the elusive qualities, individual assets and relational insights that, when cultivated to the fullest, prove most effective. Know your constituency well and personalize your message so that it can be absorbed — that is the lesson I take from Heschel, King and Mordecai Rubin in my day-to-day leadership of JTS.

We need leaders with unique strengths to meet the varying needs of the people and this moment. Our world is rife with polarization and discord, discrimination and inequality. The events of the last three months have exposed an astonishing dearth of moral clarity and empathy. Whether a prophetic voice, gifted teacher, caring pastor or brilliant community builder, we need leaders who can meet the challenges of today and tomorrow by building on their strengths in relation to their constituencies, continually recalibrating and adapting to achieve the most effective impact.

As we remember the inspiring impact of these leaders, may we remain alert to the unheralded talent of those more ordinary among us who continue to lead with courage and distinctiveness, inspiring nothing short of the extraordinary.

—

The post When Dr. Martin Luther King and Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel taught my dad to pray with his feet appeared first on Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

RSS

After False Dawns, Gazans Hope Trump Will Force End to Two-Year-Old War

Palestinians walk past a residential building destroyed in previous Israeli strikes, after Hamas agreed to release hostages and accept some other terms in a US plan to end the war, in Nuseirat, central Gaza Strip October 4, 2025. Photo: REUTERS/Mahmoud Issa

Exhausted Palestinians in Gaza clung to hopes on Saturday that US President Donald Trump would keep up pressure on Israel to end a two-year-old war that has killed tens of thousands and displaced the entire population of more than two million.

Hamas’ declaration that it was ready to hand over hostages and accept some terms of Trump’s plan to end the conflict while calling for more talks on several key issues was greeted with relief in the enclave, where most homes are now in ruins.

“It’s happy news, it saves those who are still alive,” said 32-year-old Saoud Qarneyta, reacting to Hamas’ response and Trump’s intervention. “This is enough. Houses have been damaged, everything has been damaged, what is left? Nothing.”

GAZAN RESIDENT HOPES ‘WE WILL BE DONE WITH WARS’

Ismail Zayda, 40, a father of three, displaced from a suburb in northern Gaza City where Israel launched a full-scale ground operation last month, said: “We want President Trump to keep pushing for an end to the war, if this chance is lost, it means that Gaza City will be destroyed by Israel and we might not survive.

“Enough, two years of bombardment, death and starvation. Enough,” he told Reuters on a social media chat.

“God willing this will be the last war. We will hopefully be done with the wars,” said 59-year-old Ali Ahmad, speaking in one of the tented camps where most Palestinians now live.

“We urge all sides not to backtrack. Every day of delay costs lives in Gaza, it is not just time wasted, lives get wasted too,” said Tamer Al-Burai, a Gaza City businessman displaced with members of his family in central Gaza Strip.

After two previous ceasefires — one near the start of the war and another earlier this year — lasted only a few weeks, he said; “I am very optimistic this time, maybe Trump’s seeking to be remembered as a man of peace, will bring us real peace this time.”

RESIDENT WORRIES THAT NETANYAHU WILL ‘SABOTAGE’ DEAL

Some voiced hopes of returning to their homes, but the Israeli military issued a fresh warning to Gazans on Saturday to stay out of Gaza City, describing it as a “dangerous combat zone.”

Gazans have faced previous false dawns during the past two years, when Trump and others declared at several points during on-off negotiations between Hamas, Israel and Arab and US mediators that a deal was close, only for war to rage on.

“Will it happen? Can we trust Trump? Maybe we trust Trump, but will Netanyahu abide this time? He has always sabotaged everything and continued the war. I hope he ends it now,” said Aya, 31, who was displaced with her family to Deir Al-Balah in the central Gaza Strip.

She added: “Maybe there is a chance the war ends at October 7, two years after it began.”

RSS

Mass Rally in Rome on Fourth Day of Italy’s Pro-Palestinian Protests

A Pro-Palestinian demonstrator waves a Palestinian flag during a national protest for Gaza in Rome, Italy, October 4, 2025. Photo: REUTERS/Claudia Greco

Large crowds assembled in central Rome on Saturday for the fourth straight day of protests in Italy since Israel intercepted an international flotilla trying to deliver aid to Gaza, and detained its activists.

People holding banners and Palestinian flags, chanting “Free Palestine” and other slogans, filed past the Colosseum, taking part in a march that organizers hoped would attract at least 1 million people.

“I’m here with a lot of other friends because I think it is important for us all to mobilize individually,” Francesco Galtieri, a 65-year-old musician from Rome, said. “If we don’t all mobilize, then nothing will change.”

Since Israel started blocking the flotilla late on Wednesday, protests have sprung up across Europe and in other parts of the world, but in Italy they have been a daily occurrence, in multiple cities.

On Friday, unions called a general strike in support of the flotilla, with demonstrations across the country that attracted more than 2 million, according to organizers. The interior ministry estimated attendance at around 400,000.

Italy’s right-wing government has been critical of the protests, with Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni suggesting that people would skip work for Gaza just as an excuse for a longer weekend break.

On Saturday, Meloni blamed protesters for insulting graffiti that appeared on a statue of the late Pope John Paul II outside Rome’s main train station, where Pro-Palestinian groups have been holding a protest picket.

“They say they are taking to the streets for peace, but then they insult the memory of a man who was a true defender and builder of peace. A shameful act committed by people blinded by ideology,” she said in a statement.

Israel launched its Gaza offensive after Hamas terrorists staged a cross border attack on October 7, 2023, killing some 1,200 people and taking 251 people hostage.

RSS

Hamas Says It Agrees to Release All Israeli Hostages Under Trump Gaza Plan

Smoke rises during an Israeli military operation in Gaza City, as seen from the central Gaza Strip, October 2, 2025. Photo: REUTERS/Dawoud Abu Alkas

Hamas said on Friday it had agreed to release all Israeli hostages, alive or dead, under the terms of US President Donald Trump’s Gaza proposal, and signaled readiness to immediately enter mediated negotiations to discuss the details.