Uncategorized

A New York celebration of Ladino aims to bust the myth that the Judeo-Spanish language is dead

(New York Jewish Week) — The sixth annual New York Ladino Day — which aims to celebrate and elevate Ladino culture in New York and throughout the world — will take place this Sunday at the Center for Jewish History in Manhattan.

For the first time since the pandemic, the program will be conducted in person, though a livestream option is also available. This year’s theme is “Kontar i Kantar” — “Storytelling and Singing” — and will include a performance from Tony- and Grammy-nominated Broadway singer Shoshana Bean and a conversation with Michael Frank, author of “One Hundred Saturdays: Stella Levi and the Search for a Lost World,” as well as additional music-oriented speakers and performances.

“Music is certainly one of the domains in which the language is doing well and generating new interest and new music,” said Bryan Kirschen, a professor of Hispanic Linguistics at Binghamton University and one of the event’s organizers. (Kirschen was one of the New York Jewish Week’s “36 Under 36” in 2017.)

Ladino, or Judeo-Spanish, was once the primary language spoken by Jews on the Iberian Peninsula. After the Jews’ expulsion in 1492, they brought language with them throughout the Ottoman Empire — Turkey, North Africa and the Balkans. Today, the estimated number of Ladino speakers around the world — mostly Sephardic Jews — ranges between 60,000 to 300,000, from fluent speakers to descendants who are familiar with some words.

Sephardic Jews were the first Jewish immigrants in New York, founding Congregation Shearith Israel in 1654, the oldest Jewish congregation in the United States. (It’s still in operation today at 2 West 70th St., where it has been since 1897.) Sephardic Jews remained the only active Jewish community in New York until the wave of German Jewish immigration in the early 19th century, followed by the mass immigration of Eastern European Jews that began at the tail-end of the 19th century.

Soon enough, Ashkenazi Jews quickly outnumbered New York’s Sephardic community, though Sephardic and Ladino culture continues to thrive today. Today, the main hubs for Sephardic and Ladino culture and education are the American Sephardi Federation and the Kehilla Kedosha Synagogue and Museum, a Greek Romaniote synagogue on the Lower East Side, said Kirschen, and there are large Sephardic synagogues in Canarsie, Brooklyn and Forest Hills, Queens that still conduct services in Ladino.

Ladino, said Kirschen, remains “a very living, in some ways thriving language, interestingly enough, particularly since the pandemic.”

Ahead of Sunday’s celebration — which is co-curated by Jane Mushabac, a professor emerita of English at City University of New York and a Ladino scholar and writer — the New York Jewish Week caught up with Kirschen to discuss the program, his personal interest in Ladino, and how Ashkenazi Jews can help uplift Ladino language and culture.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Kirschen, far left, leads a panel discussion during the 2020 New York Ladino Day celebration. (Courtesy Bryan Kirschen)

New York Jewish Week: How did you become interested in Ladino culture? Are you from a Sephardic family?

I’m from an Ashkenazi, Yiddish-speaking family. So I’m not Sephardic. But for the past 15 years or so, I’ve been doing my best to learn as much about and embrace Sephardic culture as I can, and learn as much as I can about Ladino as well. My own interest stems from learning languages — I’m a Spanish professor at Binghamton University and I have also studied Hebrew for numerous years. So when I first came across Ladino as this Judeo-Spanish language, it interested me for a number of reasons. Once I started to meet actual speakers, it became so much more than just about the language — it became about celebrating and promoting the culture, the history, the connections, of course the food and the music.

What is the origin story of New York Ladino Day?

The idea of Ladino Day came about in 2013 — to have a day when communities around the world would celebrate all that remains. Originally, the day was selected to be during Hanukkah. But because there is no real central organization that governs the language — though there are different institutions, particularly in Israel, that try to foster the language and help promote it — Ladino Day grew in many different directions.

These days, some communities celebrate in January, some in February, some still in December. The National Authority of Ladino in Israel has their own International Day of Ladino in March. But the important thing is that communities all around the world are committed to celebrating it in their own ways.

As far as New York goes, the American Sephardi Federation at the Center for Jewish History in Manhattan started holding a Ladino Day six years ago under the direction of my collaborator, Jane Mushabac, who is Sephardic from a Ladino-speaking family. I had been separately organizing Judeo-Spanish celebrations at a synagogue in Forest Hills, Queens, so the following year we joined forces and started co-curating the program together and have been doing that ever since.

The theme for this year’s program is “Kontar i Kantar.” How is this year’s theme different from years’ past?

Last year, we did “Salud y Vida,” which is a common expression for “health and life” and which was fitting for the time. Like most of the world, we had to pivot for the last two years and hold the program online. That afforded different opportunities — we were able to bring in speakers from around the world in a way that was much more doable, and we were able to open up our program to the world. Normally, we like to focus on New York talent and language, but the previous few years doing online events we were featuring different voices from the Sephardic world, so many new connections were made.

Because of that experience, this year’s program will be back in person at the Center for Jewish History, but with a hybrid option. The theme is “Kontar i Kantar,” “Storytelling and Singing.” It will both acknowledge how important music has been to Ladino, and celebrate how, in recent years, there have been so many initiatives for people to get together to share their stories in or about Ladino and to sing in Ladino.

Most Jews in New York have an Ashkenazi background. What role or responsibility do you think Ashkenazi Jews have in honoring and preserving Ladino culture?

Yes, the numbers [of Ashkenazi versus Sephardi Jews] don’t match up. Still, Sephardim from Turkey and areas of the former Ottoman Empire brought tens of thousands of Sephardic, Ladino-speaking Jews to New York City at the start of the 20th century, but as a minority — as a minority within the Jews, as a minority-speaking language, etc. So as someone who is Ashkenazi, I understand the enormous responsibility that I have to represent this language in a positive and genuine way to others and to work with and uplift speakers of Ladino.

Like Yiddish, thousands upon thousands of Ladino speakers were killed in the Holocaust, and those who didn’t experience the same fate often gave up their Ladino to assimilate. So many speakers today, who are typically in their 70s, 80s or 90s — or maybe younger generations who know some words here and there like foods, terms of kin — haven’t historically been so proud of using their Ladino. So aside from research and teaching, I’m really passionate about encouraging speakers and semi-speakers to use their language and to take pride in their language and ideally, to give them a platform to do so.

Bonus question: What are some common misconceptions about Ladino?

Ladino is not a dead language — that’s something I’m very vocal about. There are all sorts of ways to classify and categorize languages, but as long as they are living, breathing, speakers and semi-speakers, the language is living. So Ladino is a living language, despite all the obstacles. There are speakers and there are amazing resources out there willing to share their language and their story with people.

“Kontar i Kantar: The 6th Annual New York Ladino Day” will take place at the Center for Jewish History (15 West 16th St.) on Sunday at 2:00 p.m. A livestream option is available. Buy tickets and find more information here.

—

The post A New York celebration of Ladino aims to bust the myth that the Judeo-Spanish language is dead appeared first on Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

Uncategorized

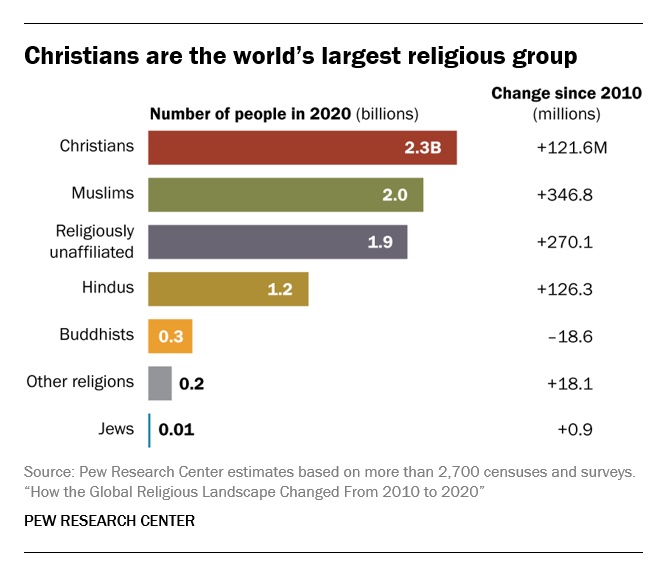

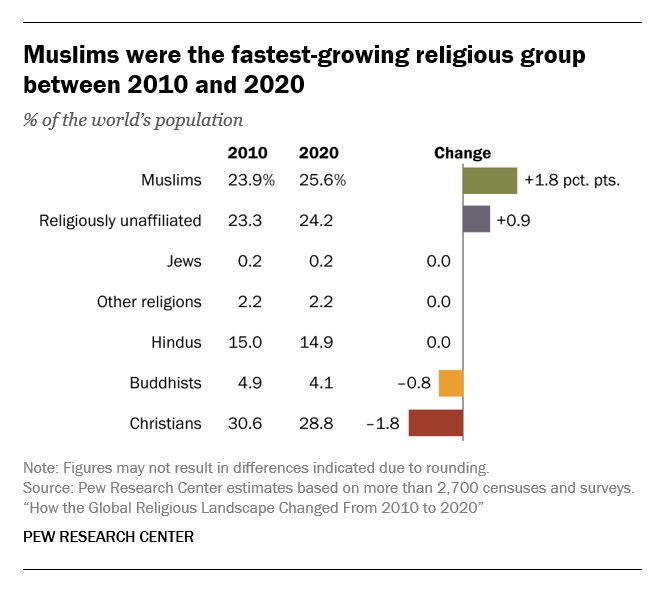

How the Global Religious Landscape Changed from 2010 to 2020

Muslims grew fastest; Christians lagged behind global population increase

• Christians are the world’s largest religious group, at 28.8% of the global population. They are a majority everywhere except the Asia-Pacific and Middle East-North Africa regions. Sub-Saharan Africa has surpassed Europe in having the largest number of Christians. But Christians are shrinking as a share of the global population, as millions of Christians “switch” out of religion to become religiously unaffiliated.

• Muslims are the world’s second-largest religious group (25.6% of the world’s population) and the fastest-growing major religion, largely due to Muslims’ relatively young age structure and high fertility rate. They make up the vast majority of the population in the Middle East-North Africa region. In all other regions, Muslims are a religious minority, including in the Asia-Pacific region (which is home to the greatest number of Muslims).

• The religiously unaffiliated population is the world’s third-largest religious category (24.2% of the global population), after Christians and Muslims. Between 2010 and 2020, religiously unaffiliated people grew more than any group except Muslims, despite their demographic disadvantages of an older age structure and relatively low fertility. The unaffiliated made up a majority of the population in 10 countries and territories in 2020, up from seven a decade earlier.

• Hindus are the fourth-largest religious category (14.9% of the world’s population), after Christians, Muslims and religiously unaffiliated people. Most (99%) live in the Asia-Pacific region; 95% of all Hindus live in India alone. Between 2010 and 2020, Hindus remained a stable share of the world’s population because their fertility resembles the global average, and surveys indicate that switching out of or into Hinduism is rare.

• Buddhists (4.1% of the world’s population) are the only group in this report whose number declined worldwide between 2010 and 2020. This was due both to religious disaffiliation among Buddhists in East Asia and to a relatively low birth rate among Buddhists, who tend to live in countries with older populations. Most of the world’s Buddhists (98%) reside in the Asia-Pacific region, the birthplace of Buddhism.

• Jews, the smallest religious group analyzed separately in this report (0.2% of the world’s population), lagged behind global population growth between 2010 and 2020 – despite having fertility rates on par with the global average – due to their older age structure. Most Jews live either in North America (primarily in the United States) or in the Middle East-North Africa region (almost exclusively in Israel).

These are among the key findings of a Pew Research Center analysis of more than 2,700 censuses and surveys, including census data releases that were delayed due to the coronavirus pandemic. This report is part of the Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures project, which analyzes global religious change and its impact on societies around the world. Funding for the Global Religious Futures project comes from The Pew Charitable Trusts and the John Templeton Foundation.

Uncategorized

Antisemitism in some unlikely places in America

By HENRY SREBRNIK Antisemitism flourishes in a place where few might expect to confront it – medical schools and among doctors. It affects Jews, I think, more emotionally than Judeophobia in other fields.

Medicine has long been a Jewish profession with a history going back centuries. We all know the jokes about “my son – now also my daughter – the doctor.” Physicians take the Hippocratic Oath to heal the sick, regardless of their ethnicity or religion. When we are ill doctors often become the people who save us from debilitating illness and even death. So this is all the more shocking.

Yes, in earlier periods there were medical schools with quotas and hospitals who refused or limited the number of Jews they allowed to be affiliated with them. It’s why we built Jewish hospitals and practices. And of course, we all shudder at the history of Nazi doctors and euthanasia in Germany and in the concentration camps of Europe. But all this – so we thought – was a thing of a dark past. Yet now it has made a comeback, along with many other horrors we assume might never reappear.

Since the Hamas attack on Israel on October 7, 2023, there has been a resurgence of antisemitism, also noticeable in the world of healthcare. This is not just a Canadian issue. Two articles on the Jewish website Tablet, published Nov. 21, 2023, and May 18, 2025, spoke to this problem in American medicine as well, referencing a study by Ian Kingsbury and Jay P. Greene of Do No Harm, a health care advocacy group, based on data amassed by the organization Stop Antisemitism. They identified a wave of open Jew-hatred by medical professionals, medical schools, and professional associations, often driven by foreign-trained doctors importing the Jew-hatred of their native countries, suggesting “that a field entrusted with healing is becoming a licensed purveyor of hatred.”

Activists from Doctors Against Genocide, American Palestinian Women’s Association, and CODEPINK held a demonstration calling for an immediate cease-fire in Gaza at the Hart Senate Office Building in Washington, D.C., Nov. 16, 2023, almost as soon as the war began. A doctor in Tampa took to social media to post a Palestinian flag with the caption “about time!!!” The medical director of a cancer centre in Dearborn, Michigan, posted on social media: “What a beautiful morning. What a beautiful day.” Even in New York, a physician commented on Instagram that “Zionist settlers” got “a taste of their own medicine.” A Boston-based dentist was filmed ripping down posters of Israeli victims and a professor at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine did the same. Almost three-quarters of American medical associations felt the need to speak out on the war in Ukraine but almost three-quarters had nothing to say about the war in Israel.

Antisemitism in academic medical centres is fostering noxious environments which deprive Jewish healthcare professionals of their civil right to work in spaces free from discrimination and hate, according to a study by the Data & Analytics Department of StandWithUs, an international, non-partisan education organization that supports Israel and fights antisemitism.

“Academia today is increasingly cultivating an environment which is hostile to Jews, as well as members of other religious and ethnic groups,” StandWithUs director of data and analytics, and study co-author, Alexandra Fishman, said on May 5 in a press release. “Academic institutions should be upholding the integrity of scholarship, prioritizing civil discourse, rather than allowing bias or personal agendas to guide academic culture.”

The study, “Antisemitism in American Healthcare: The Role of Workplace Environment,” included survey data showing that 62.8 per cent of Jewish healthcare professionals employed by campus-based medical centres reported experiencing antisemitism, a far higher rate than those working in private practice and community hospitals. Fueling the rise in hate, it added, were repeated failures of DEI (diversity, equity, and inclusion) initiatives to educate workers about antisemitism, increasing, the report said, the likelihood of antisemitic activity.

“When administrators and colleagues understand what antisemitism looks like, it clearly correlates with less antisemitism in the workplace,” co-author and Yeshiva University professor Dr. Charles Auerbach reported. “Recognition is a powerful tool — institutions that foster awareness create safer, more inclusive environments for everyone.”

Last December, the Data & Analytics Department also published a study which found that nearly 40 per cent of Jewish American health-care professionals have encountered antisemitism in the workplace, either as witnesses or victims. The study included a survey of 645 Jewish health workers, a substantial number of whom said they were subject to “social and professional isolation.” The problem left more than one quarter of the survey cohort, 26.4 per cent, “feeling unsafe or threatened.”

The official journal of the Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine concurs. According to “The Moral Imperative of Countering Antisemitism in US Medicine – A Way Forward,” by Hedy S. Wald and Steven Roth, published in the October 2024 issue of the American Journal of Medicine, increased antisemitism in the United States has created a hostile learning and practice environment in medical settings. This includes instances of antisemitic behaviour and the use of antisemitic symbols at medical school commencements.

Examples of its impact upon medicine include medical students’ social media postings claiming that Jews wield disproportionate power, antisemitic slogans at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) David Geffen School of Medicine, antisemitic graffiti at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Cancer Centre, Jewish medical students’ exposure to demonization of Israel diatribes and rationalizing terrorism; and faculty, including a professor of medicine at UCSF, posting antisemitic tropes and derogatory comments about Jewish health care professionals. Jewish medical students’ fears of retribution, should they speak out, have been reported. “Our recent unpublished survey of Jewish physicians and trainees demonstrated a twofold increase from 40% to 88% for those who experienced antisemitism prior to vs after October 7,” they stated.

In some schools, Jewish faculty are speaking out. In February, the Jewish Faculty Resilience Group at UCLA accused the institution in an open letter of “ignoring” antisemitism at the School of Medicine, charging that its indifference to the matter “continues to encourage more antisemitism.” It added that discrimination at the medical school has caused demonstrable harm to Jewish students and faculty. Student clubs, it said, are denied recognition for arbitrary reasons; Jewish faculty whose ethnic backgrounds were previously unknown are purged from the payrolls upon being identified as Jews; and anyone who refuses to participate in anti-Zionist events is “intimidated” and pressured.

Given these findings, many American physicians are worried not only as Jewish doctors and professionals, but for Jewish patients who are more than ever concerned with whom they’re meeting. Can we really conceive of a future where you’re not sure if “the doctor will hate you now?”

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.

Uncategorized

The 2025 Toronto Walk (and talk ) for Israel

By GERRY POSNER There are walks and then there are walks. The Toronto UJA Walk for Israel on May 25, 2025 was one of a kind, at least as far as Canada and Jews are concerned. The number of people present was estimated to be 56,000 people or 112,000 total shoes. (How they get to that number is bewildering to me, since there is no one counting). This was 6,000 more than last year. Whether it is true or not, take it from me, it was packed. The synagogues in Canada should be so fortunate to get those numbers in total on High Holidays. The picture here gives you a sense of the size of the crowd.

This was my first walk in Toronto for Israel and I was with my granddaughter, Samantha Pyzer (not to forget her two friends whom she managed to meet at the site, no small feat, even with iPhones as aids). The official proceedings began at 9:00 a.m. and the walk at 10:00 a.m. There was entertainment to begin with, also along the way, and at the finish as well. The finish line this year was the Prosserman Centre or the JCC as it often called. The walk itself was perhaps 4 kilometres – not very long, but the walking was slow, especially at the beginning. There were lots of strollers, even baby carriages, though I did not see any wheelchairs. All ages participated on this walk. I figured, based on what I could see on the faces of people all around me that, although I was not the oldest one on the walk, I bet I made the top 100 – more likely the top 20.

What was a highlight for me was the number of Winnipeggers I met, both past and present. Connecting with them seemed to be much like a fluke. No doubt, I missed la lot of them, but I saw, in no particular order (I could not recall the order if my life depended on it): Alta Sigesmund, (who was, a long time ago, my daughter Amira’s teacher), Marni Samphir, Karla Berbrayer and her husband Dr. Allan Kraut and family. Then, when Samantha and I made it to the end and sat down to eat, I struck up a conversation with a woman unknown to me and as we chatted, she confirmed her former Winnipeg status as a sister-in- law to David Devere, as in Betty Shwemer, the sister of Cecile Devere. I also chanced upon Terri Cherniack, only because I paused for a moment and she spotted me. As we closed in near the finish, I met ( hey were on their way back), Earl and Suzanne Golden and son Matthew, as well as Daniel Glazerman. That stop caused me to lose my granddaughter and her pals. Try finding them amid the noise and size of the crowd – but I pulled it off.

As I was in line to get food, I started chatting with a guy in the vicinity of my age. I dropped the Winnipeg link and the floodgates opened with “ Did I know Jack and Joanie Rusen?” So that was an interesting few minutes. And I was not too terribly surprised to come across some of my Pickleball family. All of these meetings, along with spotting some of my sister’s family and other cousins, were carried on with the sound of the shofar as we moved along the way. In short, this was a happening. Merchants selling a variety of products, many of them Israeli based, were in evidence and, of course, the day could not have ended without the laying of tefillin, aided by Chabad, who have perfected the procedure to take less than a minute. See the photo. Chabad had a willing audience.

Aside from the joy of sharing this experience with my granddaughter, the very presence of all these Jews gathered together for a common reason made this day very special to me. However, there was a downside to the day. The downside was that, as we began to walk back to our car there was no other way I could figure out how to return when the rains came and came. While we walked faster, we were impeded by pouring rain and puddles. But Samantha wanted to persevere, as did I. We made it, but were drenched. My runners are still drying out as I write this two days later.

What with being surrounded by 56,000 people, the noise, the slow walking, and the rain, I can still say the day was a real highlight for me – one of the better moments since our arrival in Toronto in 2012. As well as the photos we took along the way, I have the reminder of the day, courtesy of the UJA, as evidenced from the photo. It was not just the walk, but the talk that accompanied the walk that made it so worthwhile for me. I would do it again, minus the rain.