Uncategorized

‘Faust’ author Goethe’s fascination with Yiddish

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe is usually remembered as a towering figure of European culture: poet, playwright, scientist, and all-around genius of the Enlightenment.

His drama Faust opens with a scene that echoes the Book of Job, where God makes a wager with the devil over whether a good man can be led astray. What far fewer people know is that Goethe’s connection to the Bible was not just literary. He actually learned Hebrew so he could read it in the original — and his path to Hebrew ran straight through Yiddish.

Goethe was born in 1749 in Frankfurt am Main into a well-to-do Christian family. Frankfurt was also home to a densely packed Jewish quarter, the Judengasse (German for “the Jewish street”). As a boy, he ventured there, feeling both nervous and curious. In his autobiography, Poetry and Truth, published in 1833, he recalled what it was like for a German boy to step into a crowded world of people who dressed differently and spoke a strange-sounding German he called Judendeutsch (Jewish German).

But instead of fear or disdain, what stayed with him was fascination. He remembered friendly people and beautiful girls, and he was struck by the sense that the Jews carried ancient history with them into everyday life. They were, he wrote, “the chosen people of God … walking around in memory of the earliest times.” Even their stubborn attachment to tradition, he felt, deserved respect.

Goethe wanted to see more. He described how he insisted on visiting Jewish schools, attending a circumcision and a wedding, and getting a glimpse of Sukkot. Everywhere, he recalled, he was welcomed, entertained, and invited back. For an 18th-century German boy, this kind of contact with Jewish life was unusual — and it clearly made a lasting impression.

At home, Goethe was buried in languages. His father hired tutors to teach him Latin, Greek, English, French and Italian. Goethe learned quickly but soon grew bored with endless grammar drills. So he did what any restless young writer might do; he turned language learning into a game.

He invented a novel made up of letters exchanged by seven siblings scattered across Europe. Each sibling wrote in a different language: A music historian in Rome wrote in Italian, a Hamburg businessman in English, while a theology student wrote Latin and Greek. The youngest sibling stayed home and wrote in Yiddish. The effect, Goethe later suggested, was both amusing and confusing for the other characters.

That detail is telling. Goethe treated Yiddish as something playful and odd, a kind of Jewish-flavored German. But he knew it well enough to use it creatively.

In his autobiography, he describes the seven-language novel but doesn’t give it a title. We can guess, though, that his Yiddish was the Western Yiddish spoken by Frankfurt Jews at that time. A sentence like ikh vil kaafen flaash (“I want to buy meat”) would have sounded close to the local German dialect, but not quite the same.

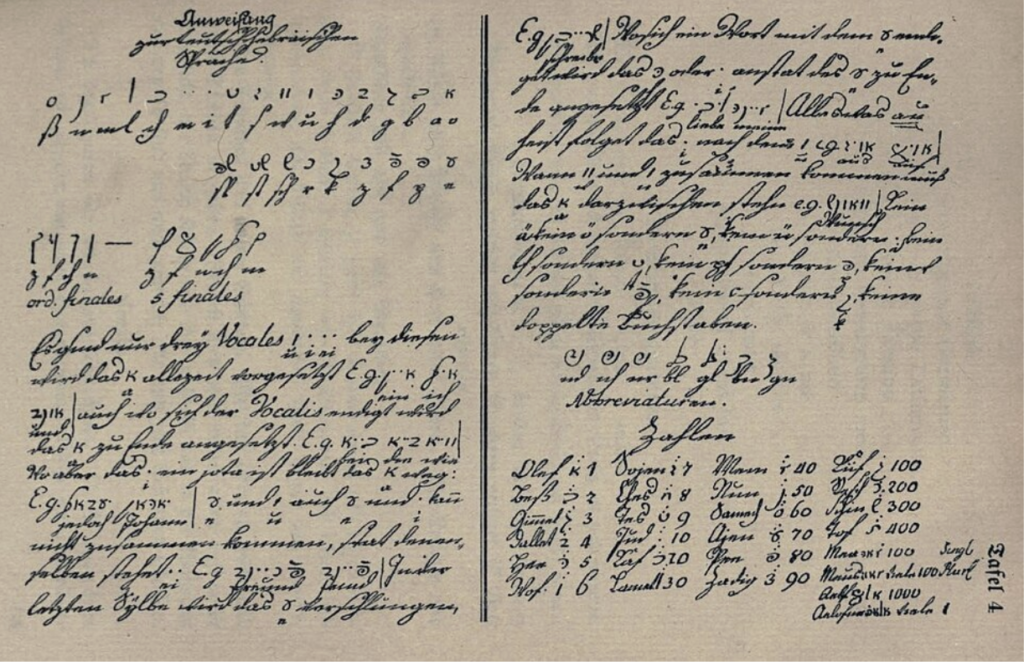

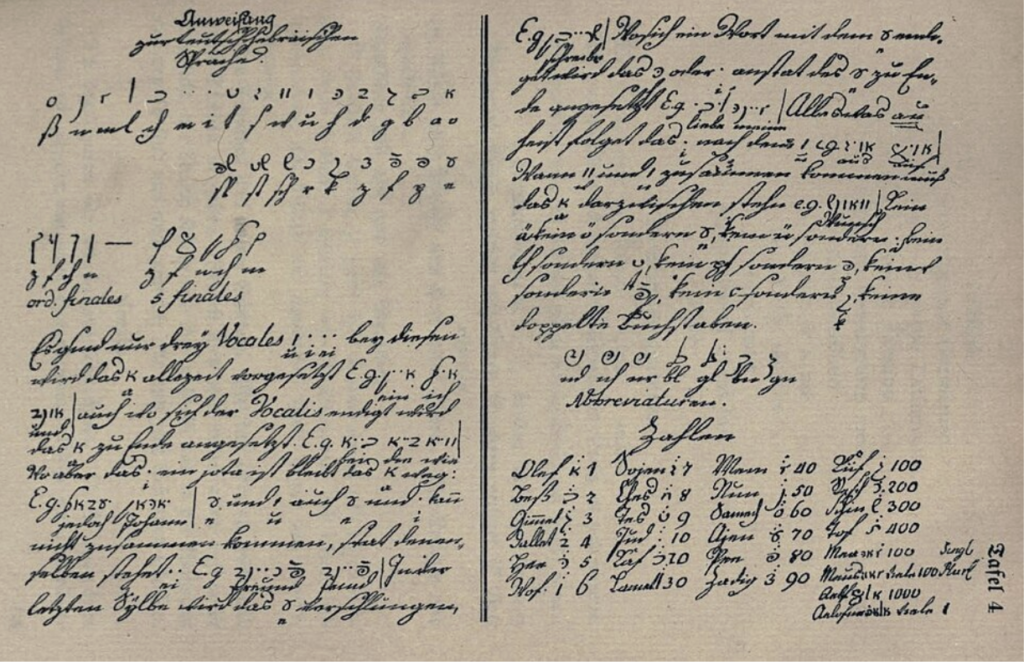

Goethe soon realized that if he wanted to understand Yiddish properly, he would have to learn Hebrew. His father arranged a tutor, and young Goethe plunged into a whole new alphabet. Although the location of his childhood notebooks are unknown, two of its pages are located online. On them, he carefully writes out the Hebrew letters, their names, sounds and even their numerical values. His notebook contains reminders to himself that Hebrew words are built from three-letter roots and urges himself to practice again and again so the forms would stick in his memory.

It wasn’t easy. Goethe later wrote that he got used to reading from right to left and identifying the letters, but was confused by all the dots and dashes — the vowel points, that seemed to complicate things even further. Still, he pushed on. He learned to read the Hebrew Bible and even tried his hand at writing a German epic based on stories from Genesis.

His interest in Yiddish didn’t disappear with childhood. When he was 17, Goethe apparently wrote a Purim play in Judendeutsch, written in Hebrew letters, complete with a translation into High German. Years later, he translated King Solomon’s Song of Songs into German. The Bible became a lifelong companion — not just as literature, but as a moral guide. “I loved and valued the Bible,” he wrote, “and owed my moral education almost entirely to it.”

As Goethe grew older, his ideas expanded in many directions. Influenced by the Jewish philosopher Baruch Spinoza, as well as Persian, Sufi and Buddhist writings, he developed a broad, inclusive worldview. He dreamed of something he called Weltliteratur — world literature — a shared cultural space where the works of all peoples could speak to one another.

Near the end of his life, Goethe said that the age of world literature had arrived, and that everyone should help bring it about. Seen this way, his childhood journey — from the Judengasse, through Yiddish, to Hebrew — was more than a youthful curiosity. It was an early step toward a vision in which cultures, languages and traditions are not sealed off from one another, but connected.

For Forward readers, there is something especially satisfying in this story. Yiddish appears here not as a joke or a dead-end dialect, but as a bridge — linking everyday Jewish life to the Bible, and even carrying one of Europe’s greatest writers toward a deeper engagement with Jewish tradition and, ultimately, with the idea of world culture itself.

The post ‘Faust’ author Goethe’s fascination with Yiddish appeared first on The Forward.

Uncategorized

A gunman attacked a Michigan synagogue. Here’s what happens to the community next

On Thursday, a driver rammed his pickup truck into Temple Israel in West Bloomfield Hills, Mich., a large Reform Temple about 25 miles from downtown Detroit. Blessedly, there were no casualties besides the shooter, whom security guards rapidly engaged. One guard was injured. Aside from that, everyone who was inside the synagogue, including 140 children attending school there, was unscathed.

“There’s hopeful news and there’s sad news about the aftermaths of these shootings,” said Mark Oppenheimer, author of Squirrel Hill: The Tree of Life Synagogue Shooting and the Soul of a Neighborhood, a methodical, lyrical look at what happened to the Pittsburgh neighborhood shattered by the Oct. 27, 2018 shooting that left 11 people dead.

The hopeful news is that older, established Jewish communities can rely on close, long-established bonds within and outside the community to get them through.

The sad news is that people unaffected by the shooting tend to move on and forget.

“So whereas this will haunt the Jewish community for years,” Oppenheimer told me in a phone interview, “most people outside the Jewish community will quickly move on to whatever the next horrible incident is.”

What happens next

Authorities have not confirmed the attacker’s motive, although he has been identified as a Michigan man who was born in Lebanon. But among all the unknowns, we do know a few things for certain.

We know that a great tragedy was averted due to the guards’ bravery and expertise, and due to the planning and preparation of synagogue leadership.

We know such attacks have gone from being extremely rare in the United States, to being more frequent.

And we know that what happens now, in the aftermath, matters a great deal.

That’s why, in writing about the worst mass shooting in American Jewish history, Oppenheimer spent most of his time researching what came after the atrocity.

“When the cameras and the police tape were gone, what stayed behind?”Oppenheimer, who teaches at Washington University’s John C. Danforth Center on Religion and Politics, wrote in the book’s introduction.

The power of connection

Both the Tree of Life synagogue and Temple Israel are older, deeply entrenched congregations with close ties to a number of local communities — Jewish and non-Jewish alike.

In one chapter of Squirrel Hill titled, simply, “Gentiles,” Oppenheimer chronicles how non-Jews came to the aid of the stricken congregation, including clergy, politicians and neighbors.

Emblematic of that was the capacity crowd of 2,500 people that came together at Soldiers and Sailors auditorium on the one-year anniversary of the shooting, where law enforcement, politicians and Christian, Muslim and Jewish clergy all spoke.

“There are usually people in government, in community organizations, in neighborhood organizations, who reach out, who want the Jews to know that they’re not alone,” said Oppenheimer.

Evidence of such connection was already on show in Michigan on Thursday. One reporter interviewed a woman praying outside the synagogue, who said, through tears, that the “Holy Spirit” had told her to turn her car around once she saw police cars racing past her to the scene, and go lend support.

In Pittsburgh, the 2018 shooting was also a time for the Jewish community itself to come together.

Squirrel Hill’s close-knit Jewish community crossed denominational divides to show support. An Orthodox rabbi organized a spreadsheet to manage the 24-hour vigils Jewish law prescribes over the bodies of the dead prior to burial.

“In Squirrel Hill, one of the nice things is there is a lot of community and solidarity across denominational lines and levels of observance,” said Oppenheimer, “and that’s pretty rare in American Judaism. It’ll be interesting to see how that plays out in Detroit.”

A new reality

Iin recent years, the need for solidarity and resilience in the face of such attacks has become, unfortunately, more apparent.

When Oppenheimer wrote his book, he was able to state the shooting was “a unique event” in American history. It’s true that until the Tree of Life massacre, antisemitic violence had claimed just 26 lives in U.S. history. The U.S., more than any Western country, and far more than Israel itself, had truly been a safe haven for Jews.

Since Squirrel Hill, six more people have died in four attacks. The previously well-earned sense of safety has been shattered.

“While the odds that any given Jew will be attacked remain quite low, it is obviously pretty terrifying,” said Oppenheimer.

Some critics of the national focus that fell on Squirrel Hill after the Tree of Life shooting argued that the tragedy got far more attention than similar mass shootings that had befallen non-Jewish communities.

But it’s the very rarity of these attacks that makes them so shocking and, at least for American Jews, so memorable.

In this new normal, it’s even more important for Jews to form strong, mutually supportive bonds among themselves, and with others.

And the world moves on

Those bonds are especially crucial because while the victims of violence don’t soon forget and move on, the world does.

“It’s a short burst of solidarity, and then people leave. Understandably so,” Oppenheimer said.

I suspect that even though prayers of gratitude and deliverance will echo through the sanctuaries of Detroit — and in Jewish hearts everywhere — the attack will haunt its intended victims long after the police tape comes down.

What will make the difference in how the community faces those fears and moves forward is the amount of support it receives from those outside it. If the broader Bloomfield and Detroit community refuses to forget this awful incident, it will change the course of healing.

I asked Oppenheimer what lesson he learned from the Tree of Life aftermath could apply to Temple Israel.

“In Pittsburgh, there was a long history of people showing up for each other,” he said Oppenheimer. “The relationships, or lack of relationships, that exist become more noticeable when something goes wrong.”

“Where there are strong ties before a shooting, there are strong ties afterwards.”

The post A gunman attacked a Michigan synagogue. Here’s what happens to the community next appeared first on The Forward.

Uncategorized

Political standoff causing DHS shutdown delays security grants for synagogues

(JTA) — A shutdown at the Department of Homeland Security since Feb. 14 is halting the review of millions of dollars in security funding for nonprofits, leaving Jewish institutions and other vulnerable groups in limbo at a moment of heightened concern about antisemitic threats.

The most recent threat came Thursday when an armed assailant rammed his vehicle into a large synagogue in suburban Detroit, where trained security forces shot at him and he was killed before he could injure anyone.

The closure stems from a political standoff over immigration enforcement: Senate Democrats are refusing to fund DHS unless the bill includes new oversight and limits on ICE operations, while Republicans and the Trump administration insist on passing funding without those changes. The dispute intensified after the killings of U.S. citizens during recent immigration operations.

Applications for the federal Nonprofit Security Grant Program, which helps synagogues, schools and community centers pay for security guards, cameras, reinforced doors and other protections were due Feb. 1 But because the program is administered through the Federal Emergency Management Agency, a component of DHS, the ongoing shutdown has frozen the process before applications could be reviewed. An effort to end the shutdown failed in the Senate on Thursday.

That means organizations that spent months preparing proposals are now waiting indefinitely to learn whether they will receive funding, at a time of rising anxiety and threats.

The grant program has become a cornerstone of security planning for Jewish institutions across the United States, especially in the wake of sometimes deadly attacks. Demand for the grants has surged in recent years as antisemitic incidents have climbed and security costs have soared.

According to data from the Anti-Defamation League, antisemitic incidents in the United States have reached historic highs in recent years, with Jewish institutions frequently targeted with threats, vandalism and harassment. Community leaders say the uncertainty surrounding the grants is arriving at precisely the wrong moment.

The NSGP is designed to distribute hundreds of millions of dollars annually to nonprofits considered at high risk of attack. Organizations submit detailed applications outlining their vulnerabilities and the security improvements they hope to fund, which FEMA then reviews and awards through state agencies.

But during a federal shutdown, most DHS personnel responsible for reviewing those applications are furloughed. As a result, the process has effectively stalled.

For many nonprofits, the delay creates practical and financial uncertainty. Security upgrades such as surveillance systems, bollards, access-control systems and trained guards often depend on the grants, and institutions typically plan their budgets around the expectation of federal support.

Jewish communal security groups say the program has been one of the most successful federal efforts to help protect religious institutions. Michael Masters, CEO of the Secure Community Network, a Jewish security nonprofit, said Jewish organizations rely on federal funding to cover essential security needs, saying that it was “a challenge” that DHS was currently not processing security grant applications.

“There’s no other faith-based community in the United States that needs to spend $760 million a year, at a minimum, on security that we do,” Masters said. “That’s a reality of the threat environment that we have to adapt to, that we have adapted to.”

The post Political standoff causing DHS shutdown delays security grants for synagogues appeared first on The Forward.

Uncategorized

A gunman rammed a Michigan synagogue. Its security preparations may have saved lives.

(JTA) — The suspected assailant, armed with rifles and smoke bombs, who rammed into Temple Israel on Thursday encountered a synagogue that was well prepared for just such an attack.

He hit and injured the congregation’s security director with his car as he plowed through the synagogue’s doors and drove down a hallway. But he didn’t manage to harm anyone else as he was found dead after trained and armed security guards shot at him

And because the rest of the staff knew exactly how to respond to an active shooter threat.

“We always worry that you can plan and plan and plan and practice and practice, and it won’t matter, because it will be something else, but it feels like a miracle that everything worked the way it was supposed to, that our team was so incredibly brave, local law enforcement’s been amazing, and that everybody’s OK,” Rabbi Jen Lader of Temple Israel told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

Oakland County Sheriff Michael Bouchard and West Bloomfield County Police Chief Dale Young also immediately praised the security response in the wake of the attack.

“I am deeply proud of the response, not only from the security that was on site, but also of all the police officers and the firefighters that are here right now, we train on active shooter events a lot,” Young said during a press conference outside the synagogue on Thursday. “I think that training certainly helped to mitigate what happened here today.”

Indeed, it was a situation that Jewish institutions across the United States have trained for, as antisemitism and threats of violence have ticked up in recent years, especially following the 2018 synagogue shooting in Pittsburgh that killed 11 Jews during Shabbat services. The rabbi of a synagogue in Colleyville, Texas, credited a security training with enabling him to respond when a man took him and three congregations hostage in 2022.

“Everybody flees danger, and our team went straight toward it, and they were the ones who neutralized the terrorist and saved everybody,” said Lader. “And our teachers followed, you know, to the absolute letter, our active shooter training and lockdown procedures, and saved every kid.”

Beyond the synagogue’s full-time director of security, Lader said Temple Israel also has a full team of armed security guards on the premises at all times as well as a remote security system that is able to secure different areas of the building during threats.

In late January, FBI agents also visited Temple Israel to train clergy and staff about how to respond to an active shooter.

According to a social media post from FBI Detroit, the Active Shooter Attack Prevention and Preparedness course “combines lessons learned from years of research and employs scenario-based exercises to help participants practice the decision-making process of the Run, Hide, Fight principles and take necessary actions for survival.”

Michael Masters, the national director and CEO of the Secure Community Network, an organization that coordinates security for Jewish institutions nationwide, said that the outcomes of the attack Thursday reflected the preparedness of Temple Israel.

“Investing in security is an investment, it’s a down payment on the Jewish future,” said Masters. “The community that made up the synagogue, the larger Detroit Jewish community, has been making that investment for years and years, and today, that investment paid off and lives [were] saved.”

Among the security measures that Masters said his organization recommended were “bollards or fences or natural obstructions” to the building, controlling access to the facility through reinforced doors or windows and having a security presence.

“What we hope this reaffirms is that security needs to be an ongoing investment in order to allow Jewish life, faith based life, to thrive,” said Masters. “And very much that investment can result, and did result, in Jewish lives being saved, and so we all need to recognize that and commit ourselves as members of the community at every level to be a part of making that investment at whatever level we can.”

In the wake of the fatal shooting of two Israeli embassy staffers in Washington D.C. in June, the synagogue hosted a town hall on hate crimes and extremism.

Among the speakers at the town hall was Noah Arbit, a lifelong congregant of Temple Israel who represents West Bloomfield in the Michigan House of Representatives. Arbit said in an interview on Thursday that after he first learned of the attack while working on the state house floor, he immediately began to cry and raced down to his home synagogue.

“I campaigned on taking on hate crimes,” said Arbit. “To be working on these issues, and then to see it come home to roost in my own community, in my own synagogue, in my hometown that I represent is, frankly, just like my worst nightmare.”

While Arbit praised the response by security and law enforcement as the attack unfolded, he said he was “outraged and enraged and deeply pained that it was necessary in the first place.”

“Jewish communities across the country and world have watched, you know, for the past decade, as our institutions have congealed into fortresses,” he said. “We are now forced to live behind, basically, you know, militarized, institutionally securitized institutions, and what a shame that is. It’s not just a shame, It’s unfathomable, it’s unforgivable.”

For Rabbi Mark Miller of Temple Beth El, another Reform synagogue a 20-minute drive away in Bloomfield Hills, the attack on Temple Israel served as a stark reminder of why security infrastructure was essential for Jewish institutions.

“This is one of those moments when, for years and years, we have bemoaned that we have to put so much time and energy into security for our institutions,” said Miller. “And this is one of those days that reminds us that we don’t have a choice.”

Miller’s synagogue had a recent security crisis of its own, when a man drove through its parking lot in December 2022 and shouted antisemitic threats as parents walked their preschoolers into the building. The assailant, Hassan Chokr, was sentenced to 34 months in prison in September for illegally possessing multiple firearms inside a gun store after leaving the synagogue.

“It’s a terrifying day, obviously for a lot of people, especially for parents with their kids at not only Temple Israel but at ours and other temples and Jewish institutions,” Miller said.

Lader said that among her congregants, two competing sentiments had jumped out: Those who “never, in a million years, in our heart of hearts, thought it was ever going to happen to us” and others who “knew it was only a matter of time before it knocked on our door.”

But another feeling was even stronger, she said.

“I think the overarching sentiment, and the one that I want to make sure gets out there, is our absolute gratitude to our internal teams, our amazing staff, local law enforcement and our teachers for really, like, a building full of absolute heroes, who were able to keep us safe,” Lader said.

The post A gunman rammed a Michigan synagogue. Its security preparations may have saved lives. appeared first on The Forward.