Uncategorized

How Abe Kugielsky’s photos of Hasidic Brooklyn ended up on display in Grand Central Terminal

When Abe Kugielsky first began photographing the Hasidic Jewish community in Borough Park, Brooklyn, in 2010, he was an outsider with a camera, met with resistance from a community unaccustomed to being documented.

But by 2017, he had amassed a bank of roughly 50,000 photographs, and decided it was time to start posting his images to an Instagram account he called “Hasidim In USA.”

Today, his account has drawn 80,000 followers curious for a glimpse inside a traditionally private world. And this month, it has also landed him a place in Humans of New York’s “Dear New York” exhibition in Grand Central’s Vanderbilt Hall. The free exhibition, curated by Brandon Stanton of the online photo sensation Humans of New York and including dozens of local photographers, runs until Oct. 19.

A view of Humans of New York’s “Dear New York” exhibition in Grand Central’s Vanderbilt Hall, running from Oct. 6 to Oct. 19. (Courtesy Abe Kugielsky)

By day, Kugielsky, who is 45 and identifies as Modern Orthodox, runs a Judaica antique auction house in Cedarhurst, Long Island. But his photography, and efforts to gain inroads in the Hasidic community, have become his true passion.

“Judaica is my full-time job, but I will close shop whenever I feel like I need a day off to go,” said Kugielsky. “It’s very therapeutic to me when I go out to shoot, I’m in my own little bubble, my own zone.”

This interview was condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

JTA: What first drew you to photographing the Hasidic communities in New York?

Kugielsky: When I moved to Brooklyn after we got married, my wife had a job in Borough Park. I would drive her to work every day. I had started street photography as a hobby back in Israel a little bit, and then got married and I let go of it. But when I started visiting Borough Park every morning, and I was getting that Roman Vishniac vibe by seeing the scenes, and I figured, I’ll pick up a camera and start documenting something that’s been untouched in New York.

It’s been very popular in Israel. There’s so many photography books on Orthodox life in Jerusalem, but there’s nothing about Hasidic life in America. There’s one book from like 1974, a small book with some photos, but that’s about it. It’s really very little. So I felt like it was an untouched niche, and I picked up a camera and I started photographing.

How do you build trust with your subjects in a community that is often described as insular?

To see someone walking on Borough Park with a camera taking pictures is not common. It’s not Mea Shearim [the Jerusalem neighborhood] where we have tourists and Americans and photographers. This is very uncommon, so there was a lot of fear of resistance, and of course, the resistance came. So it started off really more in hiding from distance, and over time, I built trust in the community to a point where they celebrate me.

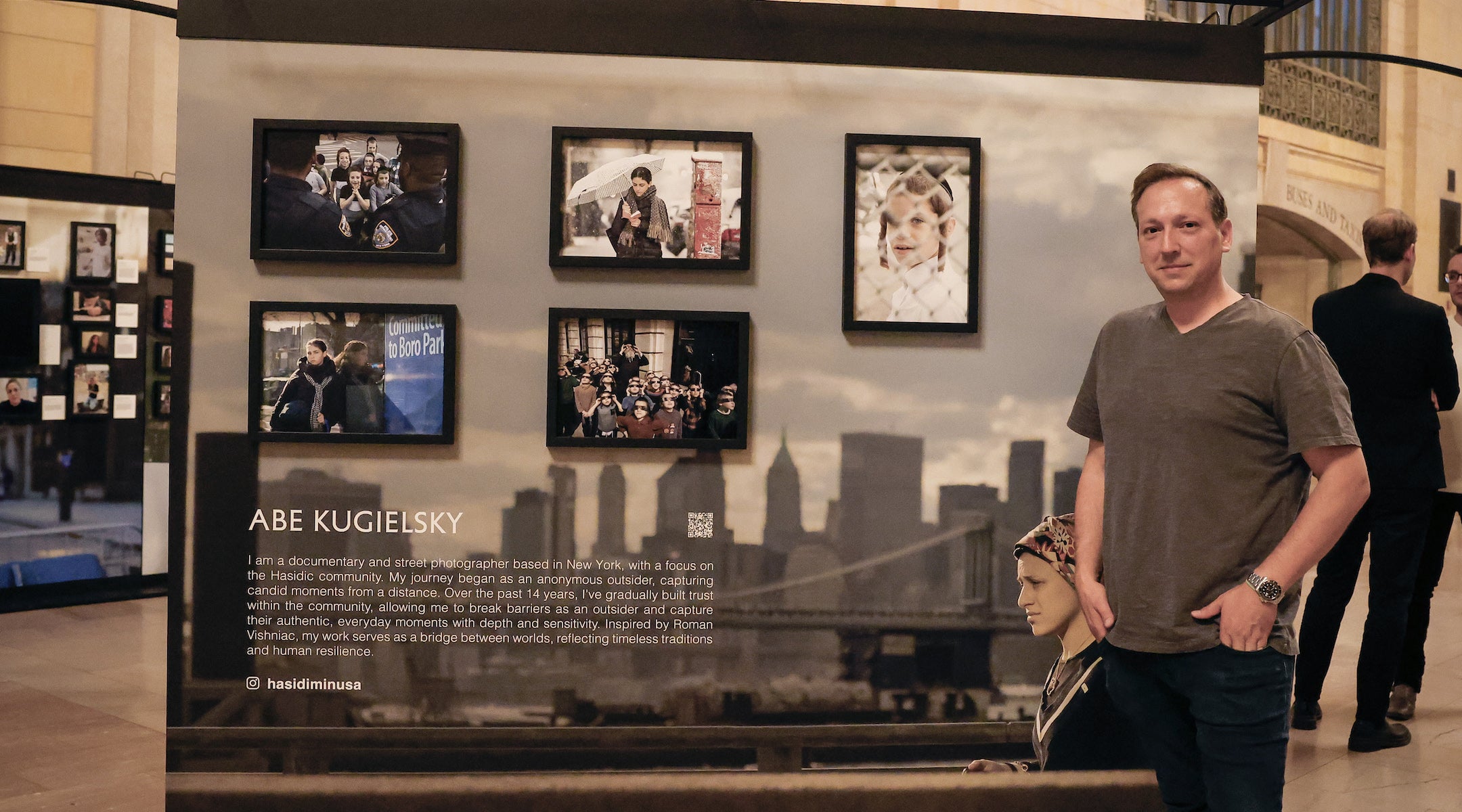

Abe Kugielsky’s installation at Humans of New York’s “Dear New York” exhibition in Grand Central’s Vanderbilt Hall, running from Oct. 6 to Oct. 19. (Courtesy Abe Kugielsky)

I made it my goal to post in a very positive light, either a positive caption or a positive scene or a positive story, to show them I’m not here to bring out what everyone else has been doing. I realized over the years that it’s really rooted a lot in generational trauma, where, whenever media came into Borough Park or Williamsburg, it was always for a negative story, and that’s where the resistance really came from. So over time, when they recognized that my work is not with that goal, they started to appreciate it more and more.

Can you tell me more about the response from the Hasidic community to your work?

I started off with an article in a local Yiddish magazine, and then a couple of months later, another article and I came out publicly with my name, my identity, so people started recognizing me more. And over time, I started getting more and more positive feedback.

I remember a woman in Williamsburg stopped me once, and she said, “I want to tell you that your photos made me fall in love again with my own culture.” So it really had a certain impact on the community, recognizing that these photos tell a positive story. It tells the story of the community that no one else does in a positive light.

“A Bridge Apart” by Abe Kugielsky. (Courtesy Abe Kugielsky)

It really shifted to the point where, if I walk down Williamsburg, people stop me and ask me for a selfie, and people will DM me and say, ‘Hey, there’s an event going on here, please come down and photograph.” My goal was to go in deeper and deeper, more and more intimate, and I’ve gotten there. Especially this past summer, we had some invites into family life, which is a whole new level that I’ve been really trying to get to.

What kinds of reactions from the public to your work have surprised or challenged you?

Of course, I get a lot of antisemitic comments from time to time with DMs. Anyone who posts anything Jewish nowadays gets them, but I’ve had a lot of interesting positive feedback from non-Jews worldwide. I’ve had people in Iran reach out to me, and I’ve heard from people in Middle Eastern countries, in Germany, Poland. I think they love the concept where they can look into another culture, have a window into another culture, something they don’t get to see.

Do you have a favorite image from the exhibit, and what makes it stand out to you?

I have one great image that I really, really love. This was a silver shop in Borough Park I walked into and I asked the owner, an older Hasidic Jew, if I can photograph him, and his response is, “What do I need it for?”

I have an album on my phone with photos I downloaded from Brooklyn Public Library, old images from Williamsburg taken by a photographer in 1964, and I figured, let me show him what it looks like looking back at photos from 50 years ago. I started showing him on my phone. He was scrolling through the photos, and I said, look how beautiful it is to look at pictures from 50 years ago.

But then he froze on a certain picture, and his demeanor changes, and he goes, “This is my wife.” He found a picture of his wife and his first newborn son from 50 years ago in those photos, so I captured that moment where he’s really reminiscing about those years.

“Silver Memories” by Abe Kugielsky. (Courtesy Abe Kugielsky)

Humans of New York has drawn criticism for a series focused on aid workers in Gaza as well as for featuring a member of Neturei Karta, a small anti-Zionist sect of the Orthodox community. Was that something you thought about before deciding to participate?

I was tagged when he posted his request for people to submit. I didn’t follow him, it’s just not really my style of work, he’s more storytelling. I went into his page, and I saw all these posts, I wasn’t sure what to make of it.

The vibe that I got was I didn’t feel an antisemitism there. I felt like he was more going with the trend, showcasing Palestinians from Gaza or Neturei Karta, more from a place of ignorance.

I believe a lot of New Yorkers, a lot of Americans, a lot of people worldwide, don’t really know and understand the conflict. It’s just in style now to hate, and it’s in style now to side with one side or the other without really understanding.

I didn’t give it a lot of hope when I submitted my photos, and I was actually surprised that he chose my photos to be included, and throughout my conversations with him, I understood that he really doesn’t understand much of the conflict.

Have you received any critical feedback about your involvement in this project?

Very, very little. I think one or two people commented like, why would you do this? But for me, A, It’s an opportunity for me, for my work, to showcase my work out there more, and, B, I thought it was so important to have a representation of Jewish life, or Hasidic life, Orthodox life, in such an important exhibition.

“Brooklyn Skies” by Abe Kugielsky. (Courtesy Abe Kugielsky)

What are you hoping people take away when they encounter your Grand Central exhibit?

What I’m expecting people to take away is really to see the humanistic side of this culture. People could be living literally a block away from the community, and not really know the community, and not understand them.

I’m hoping that this gives them a little bit more of a humanistic view of the Hasidic community, where they live, their life, their culture, their religion. After all, we’re all human, we all coexist in the same city.

—

The post How Abe Kugielsky’s photos of Hasidic Brooklyn ended up on display in Grand Central Terminal appeared first on Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

Uncategorized

He may have been the world’s most famous mime, but in this play, he won’t shut up

There is a kind of sublime poetry in Marcel Marceau’s first act.

As a young man in occupied France, Marceau (then Mangel) forged identity papers and shepherded dozens of Jewish children across the Alps to Switzerland. In scenarios where staying quiet was essential for survival, Marceau soothed his charges into silence with his own.

In Marcel on the Train, Ethan Slater and Marshall Pailet’s play of Marceau’s pre-Bip life, the world’s most famous mime is anything but silent.

The action of the play, which bounces through time back to Marcel’s father’s butcher shop and forward to a P.O.W. camp in Vietnam (don’t ask), unfolds over the course of a train ride. Slater’s Marceau is chaperoning four 12-year-old orphans, posing as boy scouts going on a hike.

The kids — played by adults — are a rambunctious lot. Marceau tries to put them at ease juggling invisible swords, performing Buster Keaton-esque pratfalls and exhausting his arsenal of Jewish jokes that circle stereotypes of Jewish mothers or, in one case, a certain mercenary business sense.

Pailet and Slater’s script toggles uncomfortably between poignancy and one-liners with a trickle of bathroom humor (the phrase “pee bucket” recurs more often than you would think.)

The terror of Marceau’s most melancholy escortee, Berthe (Tedra Millan) is undercut somewhat by her early, anachronistic-feeling declaration, “Wow, we’re so fucked.” The bumptious Henri (Alex Wyse) would seem to be probing a troubled relationship with Jewishness and passing, but does that discussion a disservice when he mentions how it wouldn’t be the biggest deal if he “sieged a little heil.” Adolphe (Max Gordon Moore) is described as “an exercise in righteousness” in the script’s character breakdown. Sure, let’s go with that.

The presence of a mute child, Etiennette (Maddie Corman), is tropey and obvious. It doesn’t suggest that she inspired him to abandon speaking in his performances, but it doesn’t dismiss that possibility either.

But the chattiness and contrived functions of the fictive children are made more disappointing by the imaginative staging maneuvering around the shtick. Slater, best known for his role in the Wicked films and as Spongebob in the titular Broadway musical, is a gifted physical performer.

When things quiet down, Pailet’s direction, and the spare set by scenic designer Scott Davis, create meadows of butterflies. Chalk allows Marceau to achieve a kind of practical magic when he writes on the fourth wall. One of the greatest tricks up the show’s sleeve is Aaron Serotsky who plays everyone from Marceau’s father and his cousin Georges to that familiar form of Nazi who takes his torturous time in sniffing out Jews.

Surely the play means to contrast silence and sound (sound design is by Jill BC Du Boff), but I couldn’t help but wonder what this might have looked like as a pantomime.

While the story has been told before, perhaps most notably in the 2020 film Resistance with Jesse Eisenberg, Slater and Pailet were right to realize its inherent stage potential. It’s realized to a point, though their approach at times leans into broad comedy that misunderstands the sensibilities of its subject.

Like Slater, who learned of the mime’s story just a few years ago, Marceau was an early acolyte of Keaton and Chaplin. But by most accounts he cut a more controlled figure — that of a budding artist, not a kid workshopping Borscht Belt bits on preteens.

The show ends with a bittersweet montage of Bip capturing butterflies (not jellyfish — you will probably not be reminded of Mr. Squarepants). It means to frame Marceau’s established style as a maturation that nonetheless retains a kind of innocence, stamped by the kids he rescued.

“You’ll live,” Berthe tells him in a moment of uncertainty. “But I don’t think you’ll grow up.”

In Marceau there was, of course, a kind of Peter Pan. But there’s a difference between being childlike and being sophomoric.

Marcel on the Train is playing through March 26 at Classic Stage Company in New York. Tickets and more information can be found here.

The post He may have been the world’s most famous mime, but in this play, he won’t shut up appeared first on The Forward.

Uncategorized

US soldier who protected Jews in POW camp during WWII to be awarded Medal of Honor

(JTA) — An American soldier who is credited with saving the lives of 200 Jewish comrades in a prisoner of war camp in Germany during World War II will receive the U.S. military’s highest decoration, the Medal of Honor.

The award to Roddie Edmonds, who died in 1985, was announced last week. It comes more than a decade after Israel’s Holocaust memorial, Yad Vashem, recognized him as a “Righteous Among the Nations” for his bravery and six years after President Donald Trump recounted his heroism during a Veterans Day parade.

Edmonds, a sergeant from Knoxville, Tennessee, was the highest-ranking soldier among a group taken prisoner during the Battle of the Bulge in January 2045 when the Nazis asked him to identify the Jews in the group. Understanding that anyone he identified would likely be killed, Edmonds made the decision to have all of the soldiers present themselves as Jews.

When a Nazi challenged him, he famously proclaimed: “We are all Jews here!”

The show of solidarity came to light only after Edmonds’ death, when a Jewish man who had been among the soldiers at the camp shared his recollection with the New York Times as part of an unrelated 2008 story about his decision to sell a New York City townhouse to Richard Nixon when Nixon was having trouble buying an apartment following his resignation as president.

When they found the article several years later, it was the first that Edmonds’ family, including his pastor son Christ Edmonds and his granddaughters, had heard about the incident. Soon they were traveling to Washington, D.C., and Israel for ceremonies honoring Edmonds, one of only five Americans to be credited as Righteous Among the Nations, an honor bestowed by Israel on non-Jews who aided Jews during the Holocaust.

As the family campaigned for a Medal of Honor, Edmonds was also the recipient of bipartisan praise from two American presidents.

“I cannot imagine a greater expression of Christianity than to say, I, too, am a Jew,” President Barack Obama said during remarks at the Israeli embassy in Washington, D.C., on International Holocaust Remembrance Day in 2016.

Three years later, President Donald Trump recounted the story at the New York City Veterans Day Parade. “That’s something,” he said. “Master Sergeant Edmonds saved 200 Jewish-Americans — soldiers that day.”

Last week, Trump called Chris Edmonds to invite him to the White House to receive the Medal of Honor on his father’s behalf, Chris Edmonds told local news outlets. The Medal of Honor ceremony is scheduled for March 2.

The post US soldier who protected Jews in POW camp during WWII to be awarded Medal of Honor appeared first on The Forward.

Uncategorized

Jewish hockey star Jack Hughes’ overtime goal propels US to historic gold medal in Olympic hockey

(JTA) — Jewish hockey star Jack Hughes scored the game-winning goal Sunday to clinch a gold medal for the U.S. men’s hockey team, its first since 1980.

The New Jersey Devils star center, who had scored twice in Team USA’s semifinal win, sent the puck between the legs of Canadian goaltender Jordan Binnington 1:41 into overtime to give the American team a 2-1 win.

“This is all about our country right now. I love the USA,” Hughes told NBC. “I love my teammates.”

The win broke a 46-year Olympic drought for Team USA, which had not taken gold since the famous “Miracle on Ice” team that upset the Soviet Union on its way to gold in 1980. The United States also won in 1960.

“He’s a freaking gamer,” Quinn Hughes, Jack’s older brother and U.S. teammate said, according to The Athletic. “He’s always been a gamer. Just mentally tough, been through a lot, loves the game. American hero.”

Quinn Hughes is a defender for the Minnesota Wild and a former captain of the Vancouver Canucks who won the NHL’s top defenseman award in 2024. He was also named the best defender in the Olympic tournament by the International Ice Hockey Federation after scoring an overtime goal to send the U.S. team to the semifinals.

The third Jewish member of the U.S. team, Boston Bruins goaltender Jeremy Swayman, won the one game he played, a Feb. 14 preliminary-round victory over Denmark.

The Hughes family — rounded out by youngest brother Luke, who also plays for the Devils — has long been lauded as a Jewish hockey dynasty. They are the first American family to have three siblings picked in the first round of the NHL draft, and Jack was the first Jewish player to go No. 1 overall. They are also the first trio of Jewish brothers to play in the same NHL game and the first brothers to earn cover honors for EA Sports’ popular hockey video game.

Jack, who had a bar mitzvah, has said his family celebrated Passover when he was growing up. Their mother, Ellen Weinberg-Hughes, who is Jewish, represented the U.S. women’s hockey team at the 1992 Women’s World Championships and was on the coaching staff of the gold-medal-winning women’s team in Milan. Weinberg-Hughes is also a member of the International Jewish Sports Hall of Fame.

Hughes’ golden goal ushered in a burst of Jewish pride on social media, with one user calling it “the greatest Jewish sports moment of all time.” The Hockey News tweeted that Hughes was “the first player in hockey history to have a Bar Mitzvah and a Golden Goal! Pretty cool!”

Jewish groups and leaders also jumped on the praise train. “Special shout out to @jhugh86 on scoring the game-winning goal!” tweeted Jonathan Greenblatt, CEO of the Anti-Defamation League. “Beyond his incredible skill on the ice, Jack makes history as a proud representative of the American Jewish community, reminding us that the Jewish people are interwoven into America in her 250th year! Mazel Tov, Jack!”

The post Jewish hockey star Jack Hughes’ overtime goal propels US to historic gold medal in Olympic hockey appeared first on The Forward.