Uncategorized

Is the movie ‘Nuremberg’ about the wrong Jewish psychiatrist?

Douglas Kelley, the real-life U.S. Army psychiatrist portrayed by Rami Malek in the recently released motion picture Nuremberg, wrote a book titled 22 Cells in Nuremberg that came out in 1947, a year after he finished his five-month stint at the Nuremberg trials.

Nearly 60 years later, interviews conducted by Leon Goldensohn, a Jewish psychiatrist who replaced Kelley at the historic war crimes trials, were published in The Nuremberg Interviews: An American Psychiatrist’s Conversations with the Defendants and Witnesses. Goldensohn who spent more time with Nazi prisoners than Kelley did, and this book, translated into 16 languages, arguably sheds more light on the Third Reich criminals.

Goldensohn and Kelley were responsible for monitoring both the physical and mental health of the Nazi prisoners, and both their lives ended tragically: Goldensohn died of a heart attack in 1961, five days after his 50th birthday; Kelley died by suicide in front of his family at the age of 45.

Leon Goldensohn’s son Dan, now 77, said that his father’s interactions with the prisoners were deeper than the ones Kelley had.

“There’s a couple of defendants who say in Leon’s book how much they preferred talking to him,” Dan Goldensohn told me.

One of those defendants was Hermann Goering, the commander of the Luftwaffe, the German air force, who complimented Goldensohn on his technique as a psychiatrist.

“I feel freer to talk to you than to some other psychologists,” Goering told him.

I checked in with Leon Goldensohn’s sons and daughter and their cousins when the movie Nuremberg opened and the actor portraying Douglas Kelley appeared larger than life on the silver screen. The movie was about “the wrong psychiatrist,” Dan Goldensohn told me over the phone.

“We lost our chance to have Leon’s work once again in the public eye, because of Kelley,” Dan said. “When people talk about an Army psychiatrist at Nuremberg, Kelley’s name comes up. Leon’s name hardly does. Anyway, we have our jealousies.”

A French production company did make an hour-long program based on the Goldensohn book that aired on The History Channel, but the psychiatrist’s surviving relatives said it was not well done. Dan Goldensohn said the family came close to signing a deal with an Italian company for a film or TV series based on the book.

“It suddenly collapsed as soon as they heard that this other movie was signed with real actors and a real director,” he said.

‘The best brother in the world’

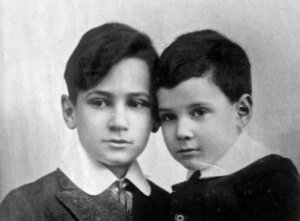

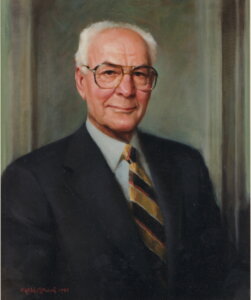

Dr. Eli Goldensohn, a world-renowned neurologist at Columbia University who died in 2013 at 98, took up the book project when he retired at the age of 83. Eli, who was four years younger than Leon, spent 10 years gathering and organizing materials, writing short summaries of all the interviews, and transcribing all those that hadn’t been transcribed. Eventually, he donated his brother’s papers to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum.

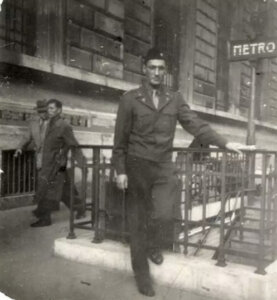

When the book was published in the fall of 2004, Eli Goldensohn told me his only disappointment was that it “didn’t really describe Leon’s wonderful war record.” Leon Goldensohn had been Division Psychiatrist of the 63rd Infantry Division, which fought in France and Germany, and received several decorations for service on the front lines.

Eli remembered his older brother fondly.

“The Nazi prisoners respected Leon because he was an objective person and was fundamentally a gentleman who was able to meet them on any level,” Eli told me back in 2004. “He was the best brother in the world. I did this book to memorialize the existence of one of the finest people I ever knew.”

Anticipating Hannah Arendt

Eli Goldensohn’s son and daughter assisted him on the book. Ellen Goldensohn, who had served as editor-in-chief of Natural History magazine for many years, helped with the copyediting. Her brother Marty Goldensohn, a veteran of public radio newsrooms, introduced Eli to his friend Jim Bouton, the former Yankee pitcher and best-selling author, who convinced Eli to pursue a deal with a major commercial publisher. (Eli ended up signing with Knopf, where the interviews were turned into a book by Ashbel Green, the editor who had worked with such dissident writers as Andrei Sakharov, Jacobo Timerman and Vaclav Havel.)

Ellen Goldensohn said her uncle Leon’s work was prescient, given that it came 17 years before Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil.

“In 1946 he really knew the banality of evil and what was asked of these people who ran the Nazi regime,” she told me.

Marty Goldensohn remembers that his mother Betty, who lived to be 101, complained about her husband commandeering the extra bedroom in their assisted living apartment for the book project.

“Eli, get these file boxes out of here or I’m going over to the other side,” she joked, the other side being the Third Reich.

Marty said his father’s labor of love on the book was motivated, in part, by a sense of history, something he shared with his brother Leon.

“Leon was a Jewish doctor and he had compassion,” Marty told me. “He was in the middle of something that the historian Tony Judt once described as ‘a seam of evil.’ He was at the seam and how could he resist asking the key questions that had to do with the horror that had been perpetrated?”

The ‘Good’ German

Of the 476 pages in The Nuremberg Interviews, 33 are devoted to Goering, who told Goldensohn he was nauseated by Picasso, referred to the virulently antisemitic newspaper Der Sturmer as “that stupid journal” and claimed that of all the accusations leveled against him, the charge of looting art treasures caused him the most anguish.

In conversations with Goldensohn, Goering insisted that he was never antisemitic, that Adolph Hitler was a great leader who was betrayed by some of his subordinates and that he, Goering, would go down in history as a man who did much for the German people.

When Leon Goldensohn pressed Goering on his culpability in the genocide of European Jewry, the prisoner gave a classic “Good German” defense: “Certainly, as second man in the state under Hitler, I heard rumors about mass killings of Jews, but I could do nothing about it and I knew that it was useless to investigate these rumors and to find out about them accurately, which would not have been too hard, but I was busy with other things,” he said. “And if I had found out what was going on regarding the mass murders, it would simply have made me feel bad and I could do very little to prevent it anyway.”

The post Is the movie ‘Nuremberg’ about the wrong Jewish psychiatrist? appeared first on The Forward.

Uncategorized

Trump has no vision for what comes next in the Middle East

Buried within the long, maudlin, combative, occasionally moving and never modest verbiage of President Donald Trump’s Tuesday State of the Union address was this uncomfortable truth: Trump has no idea what comes next in the Middle East.

In discussing two conflicts that have drawn intense attention over the past year — those in Gaza and Iran — he offered a downright confusing picture of what the future has to offer.

When the president finally touched on foreign policy, after he had already been speaking for nearly an hour and a half, he credited himself with ending eight wars — a figure that’s worth questioning.

“The war in Gaza, which proceeds at a very low level, it’s just about there,” he said.

The Gaza war is over, maybe

There is no doubt Gaza is closer to peace than it was when Trump took office. The deal he forged between Israel and Hamas is so far the greatest foreign policy accomplishment of his second term.

But “just about there?”

Israel has killed about 600 Palestinians, including many civilians, since the ceasefire. Meanwhile, Hamas has not disarmed, and in fact, according to the Times of Israel, has begun inserting itself in new Trump-backed governing bodies in Gaza.

More than 80% of the structures in the Strip were destroyed in the conflict that began when Hamas attacked Israel on Oct. 7, 2023. Rebuilding will take many years, and billions of dollars. Of the 200,000 temporary housing units humanitarian agencies estimate the enclave needs, only 4,000 have been delivered or on their way.

The much-heralded Trump peace plan, in other words, is on shaky ground.

That explains why Trump thanked Hamas, as he has done in previous speeches this month, for helping to find the bodies of dead hostages.

“Believe it or not, Hamas worked along with Israel,” Trump said, “and they dug and they dug and they dug. It’s a tough, tough thing to do, going through bodies all over, passing up 100 bodies, sometimes for each one that they found.”

Why not mention that Hamas wouldn’t have had to do such hard, noble work if it hadn’t attacked and killed Israelis in the first place? Because the odd compliment — thanking murderers for returning their victims’ bodies — was Trump playing to reality. If his signature diplomatic initiative is to succeed, he needs Hamas and its patrons to go along. So far, the group is stalling when it comes to disarmament. If he can’t persuade them to take that step, his signature peace effort is done for.

An awareness of just how treacherous this situation is explains why Trump’s Gaza comments focused largely on his success at negotiating the return of Israel’s hostages, both living and dead.

“And those parents who had a dead son,” Trump said, “they always told me that boy, they wanted him as much as though he were living.”

Trump didn’t offer a vision, as he has in the past, of a prosperous Gaza; of Saudi Arabia joining the Abraham Accords; and of Israel at peace with its neighbors. He didn’t even mention his pet initiative, the Board of Peace — surprising, given that the body met for the first time just last week. The Middle East has a way of lowering expectations, and in the State of the Union, Trump wasn’t selling anything but the successful return of the dead.

The Iran war that isn’t, yet

On Iran, Trump was, if possible, even more confusing.

The United States has sent its largest military force in decades to the Middle East, which means we are once again — maybe — on the verge of a Middle East war. But Trump’s case for conflict — and explanation of how things got to this point — was lackluster.

He claimed that Operation Midnight Hammer, the June 2025 U.S. strike on Iran’s nuclear facilities, “obliterated Iran’s nuclear weapons program.”

But evidently, a program that was “obliterated” is somehow, less than a year later, an imminent threat. In the very next sentence, Trump said Tehran is now trying to rebuild its nuclear facilities and develop missiles that could reach the United States. (The simpler and more factual explanation: actually, nothing got obliterated in the first place.)

While claiming that the Iranian regime recently killed 32,000 of its own people during nationwide protests — an exact death toll is still elusive — he offered the country a path to survival: give up nuclear weapons.

But what sounds like a clear demand really isn’t. Nuclear diplomacy takes a long time and great delicacy. Trump, who favors swift resolutions, has backed himself into a corner: The military is already there, and the world is waiting with baited breath.

Plus, Americans don’t want to go to war. Some 49% of Americans oppose an attack on Iran, with just 27% in support of one, according to a YouGov poll this month. Independents oppose the idea by 54%, and Republicans support it by only 58%.

What’s a president who has staked his second-term reputation on his ability to win big and make peace supposed to do?

For now, the lack of specificity gives Trump room to waffle on whether or not to go to war — and try to make a case for what specific, achievable aims he would have in doing so.

In a clear sign that he doesn’t yet have answers for those questions, Trump’s language on Tuesday sounded awfully familiar. “I will never allow the world’s number one sponsor of terror to have a nuclear weapon,“ he said. “My preference is to solve this problem through diplomacy.”

Compare that to former President Barack Obama’s 2012 State of the Union.

“Let there be no doubt: America is determined to prevent Iran from getting a nuclear weapon,” Obama said, “and I will take no options off the table to achieve that goal. But a peaceful resolution of this issue is still possible, and far better.”

Maybe Trump has a clear idea of what comes next for Gaza and Iran. Or maybe we’ve just gone back to the future.

The post Trump has no vision for what comes next in the Middle East appeared first on The Forward.

Uncategorized

Memories of a subway passenger

דערצויגן געוואָרן אין דער שטאָט ניו־יאָרק, בײַ אַ משפּחה וואָס האָט נישט פֿאַרמאָגט קיין אויטאָ, האָב איך אַ גרויסן חלק פֿון מײַן לעבן „אויסגעלעבט“ אויף דער אונטערבאַן („סאָבוויי“). הגם הײַנט פֿאָר איך בדרך־כּלל מיט מיט דער מחוץ־שטאָטישער באַן „מעטראָ־נאָרט“, מוז איך מודה זײַן, אַז מײַנע יאָרן אויף דער אונטערבאַן האָבן זיכער געהאָלפֿן צו אַנטוויקלען בײַ מיר דאָס געפֿיל פֿון אַן עכטן ניו־יאָרקער.

אין עלטער פֿון 11 יאָר, למשל, זענען איך און מײַן 10־יאָריקע שוועסטער, גיטל, יעדע וואָך, נאָך די קלאַסן, געפֿאָרן מיט דער אונטערבאַן פֿינף סטאַנציעס צו אונדזער פּיאַנע־לעקציע. וואָס איז דער חידוש, פֿרעגט איר? איר קענט זיך אויסמאָלן, אַז צוויי אומשולדיקע מיידלעך, טראָגנדיק קליידלעך און צעפּלעך, זאָלן הײַנט פֿאָרן, אָן שום באַגלייטונג פֿון אַ דערוואַקסענעם — אויף דער אונטערבאַן? איך — נישט. פֿונדעסטוועגן, מיין איך, אַז דאָס האָט אונדז געגעבן אַ געוויסן נישט־באַוווּסטזיניקן קוראַזש, וואָס פֿעלט הײַנט די קינדער, וואָס זייערע עלטערן מוזן זיי פֿירן אינעם אויטאָ פֿון איין אָרט צום צווייטן.

איך האָב ליב געהאַט צו לייענען די רעקלאַמעס אין וואַגאָן. איך געדענק, למשל, די מעלדונגען וועגן דעם יערלעכן שיינקייט־קאָנקורס, „מיס סאָבווייס“. עטלעכע וואָכן פֿאַרן קאָנקורס, איז אין יעדן וואַגאָן געהאָנגען אַ בילד פֿון די זעקס פֿינאַליסטקעס. פֿלעג איך מיט גיטלען איבערלייענען זייערע קליינע ביאָגראַפֿיעס — בדרך־כּלל, סטודענטקעס, סעקרעטאַרשעס, זינגערינס, און טענצערינס — און דיסקוטירן מיט איר, ווער ס׳וואָלט געדאַרפֿט געווינען די „אונטערערדישע קרוין“. איך פֿלעג זיך אָפֿט מאָל חידושן, ווי אַזוי איינע מיט אַ גרויסער נאָז אָדער געדיכטע ברעמען האָט דערגרייכט אַזאַ מדרגה, אַז איר פּנים זאָל באַצירן יעדן וואַגאָן פֿון דער ניו־יאָרקער באַן־סיסטעם.

איך האָב זיך אויך געלערנט מײַנע ערשטע שפּאַנישע זאַצן אויף דער אונטערבאַן. אין יעדן וואַגאָן איז געהאָנגען אַ וואָרענונג אויף ענגליש און אויף שפּאַניש: „די רעלסן פֿון דער אונטערבאַן זענען געפֿערלעך. אויב די באַן שטעלט זיך אָפּ צווישן די סטאַנציעס, בלײַבט אינעווייניק. גייט נישט אַרויס. וואַרט אויף די אינסטרוקציעס פֿון די קאָנדוקטאָרן אָדער דער פּאָליציי“. גיטל און איך האָבן זיך אויסגעלערנט אויף אויסנווייניק די שפּאַנישע שורות, און זיי איבערגעחזרט אַזוי פֿיל מאָל, ביז די ווערטער האָבן זיך בײַ אונדז אַראָפּגעקײַקלט פֿון דער צונג ווי בײַ אמתע פּוערטאָ־ריקאַנער. און ס׳איז אונדז צו ניץ געקומען: אַז מיר זענען געשטאַנען ערגעץ צווישן מענטשן, און געוואָלט אויסזען ווי אמתע שפּאַניש־רעדער, האָבן מיר אויסגעשאָסן די שפּאַנישע שורות מיט אַזאַ טראַסק, אַז אַ נישט־שפּאַניש רעדער וואָלט געקענט מיינען, מיר טיילן זיך מיט עפּעס אַ זאַפֿטיקער פּליאָטקע.

מײַנע דרײַ בנים האָבן שטאַרק ליב געהאַט צו פֿאָרן אויף דער אונטערבאַן. קינדווײַז פֿלעגן זיי צודריקן די פּנימלעך צו די פֿענצטער, סײַ ווען די באַן איז געפֿאָרן אין דרויסן, סײַ אינעם פֿינצטערן טונעל. מײַן עלטסטער, יאַנקל, האָט צוויי מאָל געפּרוּווט צו פֿאַרווירקלעכן זײַנס אַ חלום: צו פֿאָרן, במשך פֿון איין טאָג, אויף יעדער ליניע פֿון דער גאַנצער סיסטעם, פֿון דער #1 ביז דער #7; פֿון דער A־באַן ביז דער Z. (מע דאַרף האָבן אַ מאַטעמאַטישן קאָפּ דאָס אויסצופּלאָנטערן.) ביידע מאָל האָט יאַנקל באַוויזן צו פֿאָרן אויף אַלע ליניעס… אַחוץ איינער. נישט קיין חידוש, אַז בײַ אונדז אין דער היים איז יאָרן לאַנג געהאָנגען אינעם שפּריץ אַ פֿירהאַנג מיט אַ ריזיקע מאַפּע פֿון דער אונטערבאַן.

הײַנט האָב איך אַ ספּעציעלע הנאה צו פֿאָרן אויף דער אונטערבאַן מיט מײַנע אייניקלעך. פּונקט ווי עס האָבן קינדווײַז געטאָן זייערע טאַטעס, קוקן זיי אויך אַרויס פֿון פֿענצטער און קאָמענטירן וועגן אַלץ וואָס פֿליט פֿאַרבײַ. ווער ווייסט? אפֿשר וועלן זיי אויך מיט דער צײַט זיך אויסלערנען די ציפֿערן און אותיות פֿון יעדער באַנליניע און דערבײַ אַליין פֿאַרוואַנדלט ווערן אין עכטע ניו־יאָרקער.

The post Memories of a subway passenger appeared first on The Forward.

Uncategorized

Trump administration files lawsuit against UCLA, saying it failed to protect Jewish and Israeli employees

(JTA) — The Department of Justice filed a federal lawsuit Tuesday accusing the leadership of UCLA of allowing an antisemitic work environment on campus, intensifying the Trump administration’s long-running scrutiny of the Los Angeles campus.

The lawsuit, filed in federal court in the Central District of California, alleges UCLA failed to protect Jewish and Israeli faculty and staff from harassment following the Hamas-led Oct. 7, 2023, attack on Israel and the protests that spread across American universities afterward.

The complaint was filed the same day President Donald Trump is scheduled to deliver the first State of the Union address of his second term, in which he is expected to cite the administration’s broader confrontations with higher education institutions as evidence of its successes. It also comes roughly three months after nine Justice Department attorneys resigned from the government’s University of California antisemitism investigation, telling the Los Angeles Times they believed the probe had become politicized.

The lawsuit says that antisemitic conduct at UCLA became widespread after Oct. 7 and persisted through the 2023-24 academic year. According to the lawsuit, Jewish and Israeli employees were subjected to threats, classroom disruptions, antisemitic graffiti and, at times, were blocked from parts of campus during protests.

The government places particular emphasis on the spring 2024 Royce Quad encampment, when pro-Palestinian demonstrators established a tent protest in the center of campus. The Justice Department alleges UCLA failed to enforce its own campus rules, allowing protests that disrupted university operations and contributed to what it describes as a hostile workplace.

“Based on our investigation, UCLA administrators allegedly allowed virulent anti-Semitism to flourish on campus,” Attorney General Pamela Bondi said in a DOJ press release announcing the lawsuit. Harmeet K. Dhillon, who leads the department’s Civil Rights Division, described the alleged incidents as “a mark of shame” if proven true.

UCLA officials rejected the government’s characterization, pointing instead to changes made under Chancellor Julio Frenk.

“As Chancellor Frenk has made clear: Antisemitism is abhorrent and has no place at UCLA or anywhere,” vice chancellor of strategic communications Mary Osako said in a statement. She cited investments in campus safety, the launch of UCLA’s Initiative to Combat Antisemitism, the reorganization of the university’s civil rights office, the hiring of a dedicated Title VI and Title VII officer and strengthened protest policies.

“We stand firmly by the decisive actions we have taken to combat antisemitism in all its forms, and we will vigorously defend our efforts and our unwavering commitment to providing a safe, inclusive environment for all members of our community,” Osako said.

Frenk, who is Jewish, has spoken publicly about antisemitism in higher education. In an essay published by the Jewish Telegraphic Agency last year, he invoked the history of German universities under Nazism, warning that those institutions “never recovered after driving Jews out” and urging American colleges to confront antisemitism while preserving academic freedom and open debate.

The new lawsuit follows earlier legal battles over campus protests at UCLA. In July 2025, the university agreed to pay $6.13 million to settle a lawsuit brought by Jewish students and a Jewish professor who said demonstrators had blocked access to parts of campus. Under that agreement, UCLA said it would ensure protesters could not restrict movement or access to university spaces.

Campus tensions over speech and security have continued more recently. Bari Weiss, the journalist and founder of The Free Press, withdrew this month from a scheduled appearance at UCLA as part of the Daniel Pearl Memorial Lecture series. Weiss had been invited to speak on “The Future of Journalism” but canceled the event, citing security concerns ahead of the lecture.

The post Trump administration files lawsuit against UCLA, saying it failed to protect Jewish and Israeli employees appeared first on The Forward.