Uncategorized

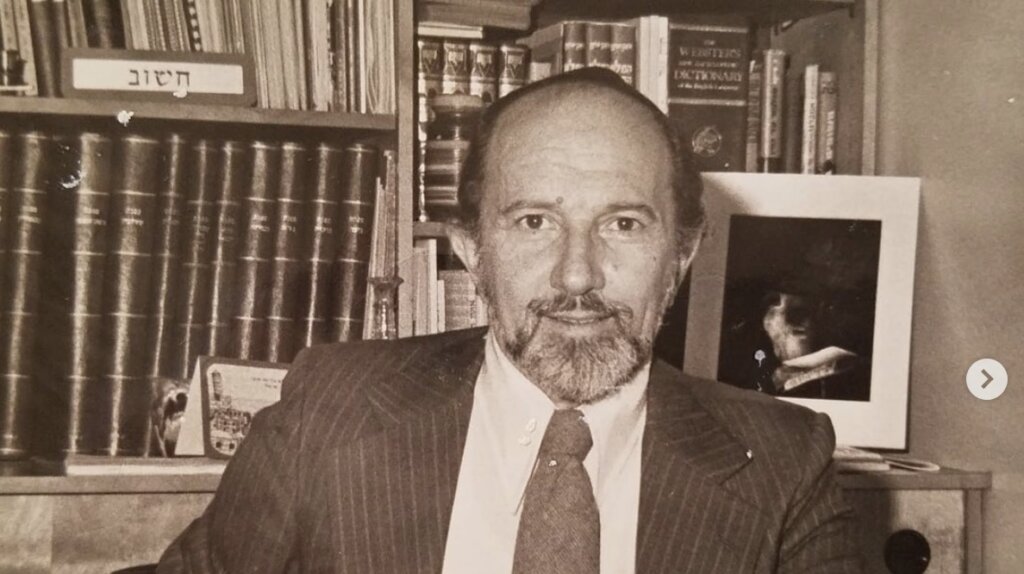

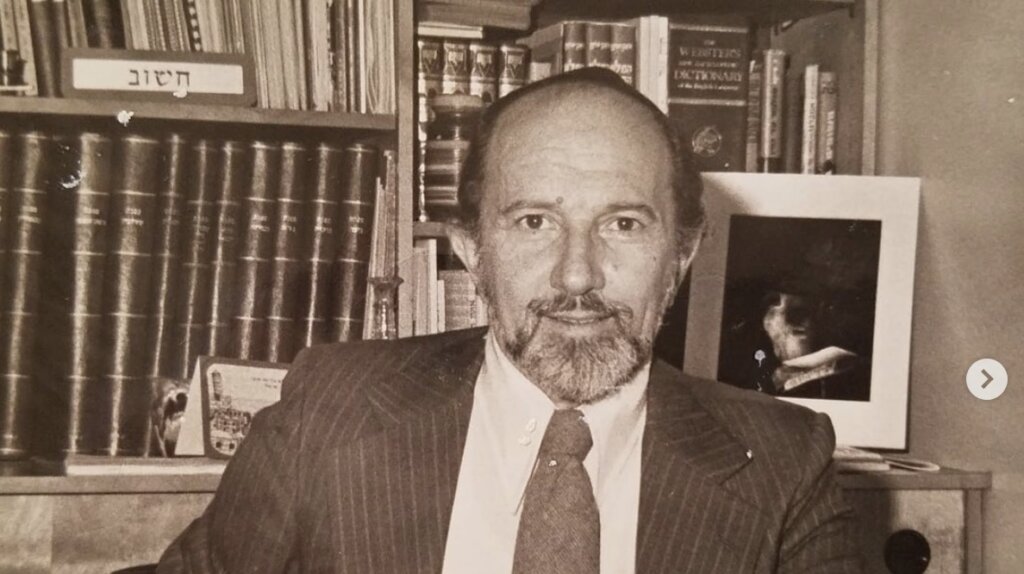

Rabbi Mayer Moskowitz z”l, on Hasidic life in pre-war Czernowitz

[The following is an English version of the original Yiddish article, which you can read here.]

Rabbi Mayer Moskowitz, a beloved longtime educator at the Ramaz School in New York and the Hebrew-immersive Camp Massad, and author of the book A Memoir of Sanctity, has passed away.

In 2010, I interviewed Rabbi Moskowitz to learn what the Hasidic community was like in the city where he was born and raised — Czernowitz (Chernivtsi), then part of Romania, and today Ukraine.

Most contemporary scholars of East European Jewish history focus on prewar Czernowitz as a hub of intellectual and cultural Jewish life; as the location of the first Yiddish conference in 1908; as the milieu where the poet Itsik Manger and fabulist Eliezer Shteynbarg produced their greatest work.

But as the oldest child of the Shotzer Rebbe — Avrohom Chaim Moskowitz, Mayer Moskowitz had a very different perspective of the city, describing it as a center of five Hasidic dynasties and a vibrant Orthodox Jewish community.

I met Rabbi Moskowitz through my son, Gedaliah Ejdelman, who was a student in his class on halacha (Jewish law) at Ramaz Upper School. The following anecdote gives you an idea of the kind of person Rabbi Moskowitz was:

On the day before the final exam, one student asked if he could write his answers in English rather than Hebrew. Half-jokingly, the rabbi told the students that they could respond in any language they wished.

Gedaliah raised his hand and asked if he could write in Yiddish. “Sure,” Rabbi Moskowitz said. So Gedaliah did, citing Rashi and other commentators in mame-loshen. Moskowitz was so delighted by the Yiddish responses that he shared them with his colleagues.

When I met with Rabbi Moskowitz in his Upper East Side apartment in Manhattan, I asked him what life was like in Czernowitz. He told me he was born in 1927, a son — in fact, the only son — of the Shotzer Rebbe, Avrohom Chaim Moskowitz. He explained that Czernowitz had no less than five Hasidic dynasties. Besides his father, there was the Boyaner Rebbe; the Nadvorner Rebbe; the Zalischiker Rebbe and the Kitover Rebbe.

“All the Rebbes were related because the marriages of their children were arranged solely with other rabbinical families in Czernowitz,” he said.

Every Rebbe had his own court of Hasidim but there were marked differences between the Rebbe and his worshippers. The former wore beards and peyes (Yiddish for sidelocks) and donned a shtreimel for the Sabbath and holidays, while their worshippers, seeing themselves as “modern Jews,” were clean-shaven and came to services wearing a tsilinder (top hat) and tailcoat.

“I myself had little peyes,” Rabbi Moskowitz said.

His family lived in the same building as his father’s shul. His mother, Alte Sheyndl, was a daughter of the Pidayetser Rebbe, so she wore a sheitel. But, like the other rebishe kinder (Rebbe’s children), she was apparently influenced by the cosmopolitan character of the city. In contrast to her husband who spoke Yiddish with their children, the Rebbetzin spoke German. She went to the theater, read secular Yiddish poetry and shook men’s hands. On Mother’s Day, little Mayer would bring her a bouquet of flowers and on New Year’s Eve the Rebbetzin and the other daughters of rabbinical families threw a party.

“On New Year’s Eve they came to our apartment on the second floor, elegantly dressed, ate and spent many hours together,” Rabbi Moskowitz said. “Although they didn’t drink any alcohol, the daughters-in-law of the Bayoner Rebbe smoked thin cigarettes.”

Rabbi Moskowitz recalled his first day in cheder at the age of three: “My parents never walked together in public but on that day they dressed me in completely new shorts, shoes and a talis-kotn.” The latter is the traditional four-cornered fringed garment that Orthodox men and boys wear under their shirt.

His parents walked him, hand-in-hand, to the cheder. When they arrived, his father wrapped him in a tallis and carried him inside. On the table, little Mayer saw the diminutive of his name, ‘Mayerl,’ written with large golden letters.

The teacher asked him to repeat each Hebrew letter and its corresponding sound. Every time little Mayer correctly repeated it — “Komets alef ‘o’ … komets beyz ‘bo’ — a honey cookie dropped onto the table in front of him.

“I really thought it was falling from the heavens,” Rabbi Moskowitz said. “As it says in Proverbs: ‘Pleasant words are as a honeycomb, sweet to the soul, and health to the bones.’”

When he was five, Mayer began learning khumesh, the Bible. “It was shabbos afternoon. My relatives, family friends and all five Rebbes came. They lifted me onto the table. I was wearing a brown velvet suit. Each grandfather gave me a golden watch with a little chain and attached it to my suit. Then they asked me: ‘What are you learning in khumesh now?’”

After the quiz was over, the guests began dancing and singing, eating cake and fruit. All the Rebbes wore shtreimels as they sat at tables surrounded by their Hasidim and handed out shirayim — remnants of the blessed food that a Rebbe would give his followers, who believed they would receive a spiritual blessing by eating it. Mayer sat between his grandfathers.

Every morning Mayer went to cheder and three afternoons a week he attended a Zionist Hebrew-language school. In 1936, at the age of ten, he was sent to the city of Vizhnitz (today — Vyzhnytsia, Ukraine) to learn in the yeshiva of the Vizhnitzer Rebbe. He came home only four times a year: on the shabbos of Hanukkah, Passover, Shavuot and Sukkot.

Rabbi Moskowitz remembers Sukkot in Czernowitz: “All year, men and women ate together but not on Sukkot. My mother blessed the holiday candles, came into the sukkah for kiddush and hamotzi but then went back into the house where she ate in the company of the other women in the family.”

The sukkah was large. His father’s Hasidim would gather around their Rebbe’s tish (table) on the second night of Sukkot for the all-night celebration called simkhas-beis-hashoeivah. About 150 men would squeeze into the sukkah. But contrary to tradition, no one slept in it. “It was cold and a bit dangerous,” Rabbi Moskowitz said.

The Shotzer Rebbe’s house also served as an inn for rebbes from surrounding towns, when they needed to come to Chernovitz to see a doctor. Simple Jews, who leased land from non-Jewish noblemen would also come to the inn to see their rebbes. “They were common people, wore workboots and would bring fruit from their fields as a gift for the Rebbe,” he explained.

Many times, impoverished Jews would come to his father’s door asking for money. “One of them, called Fishele, used to say ‘I love you’ to my mother. She was indeed a beautiful woman. So my family would invite him in and feed him the same food we were eating.”

In describing these simple everyday events of his childhood in Czernowitz, Rabbi Moskowitz did a true mitzvah: He enabled us to see the city not only as a magnet for Yiddish writers and cultural activists, but also as a large, thriving Hasidic community.

The post Rabbi Mayer Moskowitz z”l, on Hasidic life in pre-war Czernowitz appeared first on The Forward.

Uncategorized

AIPAC defends $2.3M spend against ‘pro-Israel’ politician in NJ-11, where anti-Israel candidate is prevailing

(JTA) — If AIPAC has any regrets about pouring more than $2 million into opposing a candidate who calls himself pro-Israel — and is set to lose to an anti-Israel opponent — it isn’t saying so. In fact, the pro-Israel group’s affiliated super PAC suggests it would do it again.

“We are going to have a focus on stopping candidates who are detractors of Israel or who want to put conditions on aid,” Patrick Dorton, a spokesperson for the United Democracy Project, said in an interview.

The target of the UDP’s recent spending was Tom Malinowski, a former congressman running in a special election in New Jersey’s 11th Congressional District. Malinowski, who calls himself pro-Israel and has been endorsed by the liberal Zionist organization J Street, has said he’d be open to placing conditions on some U.S. aid to Israel.

AIPAC pummeled Malinowski with $2.3 million in negative ads — but not about Israel. Instead, the ads tarred him from a progressive angle — one emphasized his vote on a 2019 bill that included increased funding for ICE, the immigration enforcement agency.

By one measure, AIPAC’s spend could be seen as a success: The candidate it opposed, seen as a favorite, did not score an easy win on Election Day. But in another crucial way, the effort appears to have backfired by throwing open the door for Analilia Mejia, a progressive grassroots organization leader who is far more critical of Israel.

The race is too close to call, but Mejia, who was the national political director for Bernie Sanders’ 2020 presidential campaign, is ahead by nearly 900 votes with 4,800 left to count. Tahesha Way, the former lieutenant governor of New Jersey who is thought to have been AIPAC’s preferred candidate, finished in a distant third.

Critics, including AIPAC supporters, have slammed AIPAC’s strategy in the race.

“They could not have gotten a worse result than what they got,” said Alan Steinberg, a journalist in New Jersey who was an EPA administrator under George Bush. “I’m a very pro-AIPAC person, very supportive of AIPAC, but this is one of the worst strategic errors that they could’ve ever made.”

The UDP got into the race because of Malinowski’s comments on U.S. aid to Israel at a time when a large number of Democrats, and some Republicans, were expressing new openness to attaching conditions to the aid as they sought to press Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to end the war in Gaza and adopt different policies in Israel and the West Bank.

Asked last fall about the possibility of conditioning or suspending aid to Israel, Malinowski told Jewish Insider that he “would make case-by-case judgments given what’s happening on the ground.” He said he would similarly make case-by-case judgments for any U.S. ally receiving aid.

“We had very serious concerns about Tom Malinowski, who clearly was open to conditioning aid to Israel,” Dorton said. “He knew that he had moved to what is not a pro-Israel position.”

Dorton indicated that the UDP would likely go after other candidates who have expressed openness or interest in conditioning aid. “Adding conditions to aid to Israel, and undermining the U.S. relationship, is a top priority for us in assessing candidates,” he said.

In New Jersey, the result could be elevating a politician whose stance on Israel is much harsher. Mejia has accused Israel of committing a genocide in Gaza and pledged not to take any AIPAC-funded trips to the country. She also began calling for a ceasefire in Gaza within weeks of Hamas’ Oct. 7, 2023, attack on Israel after tweeting on Oct. 10, “Every fiber of my being is horrified beyond words at what is furthering in Gaza. Yet again we see how oppression & dehumanization leads to despair & unthinkable destruction.”

Mejia’s campaign focused on affordability and she drew endorsements from progressives including Bernie Sanders, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Ro Khanna. If she holds her lead, she will become the Democratic nominee for April’s special election to fill the House seat vacated by now-governor of New Jersey, Mikie Sherrill.

Steinberg said he thought that AIPAC “never took seriously the possibility of her winning in this primary,” and that Malinowski would be far more aligned with AIPAC on Israel.

“I don’t think Malinowski is anti-Israel,” said Steinberg. “I know Tom, I disagree with him on Israel, but he is much preferable to Analilia Mejia. Much preferable.”

Jeremy Ben-Ami, the president of J Street, which endorsed Malinowski, wrote in a Substack column that AIPAC was responding to criticism of the Israeli government’s policies as if it were hostility toward the country itself.

“AIPAC now treats even good-faith criticism from friends as a threat to be crushed,” he wrote.

Dorton downplayed the impact of a Mejia primary victory because the upcoming special election decides only which candidate fills the seat until the end of 2026. A second primary, held in June 2026, will decide the Democratic nominee for the regular November election.

But others are viewing her potential win as a larger victory for progressives, and specifically the pro-Palestinian movement.

“Analilia Mejia for New Jersey just set a new precedent in NJ and beyond,” wrote pro-Palestinian activist Linda Sarsour in a Facebook post on Monday featuring a photo of Mejia raising her hand as the lone candidate indicating that she believed Israel committed genocide, at a forum hosted by the Council on American-Islamic Relations. “She’s teaching us that it’s okay to stand alone so as [sic] long as you are on the right side of history.”

The UDP has spent millions on congressional races to mixed results since AIPAC began directly funding candidates in 2021; it had previously worked only to cultivate support for Israel among politicians. In 2024, it spent at least $14.5 million against the incumbent “Squad” member Jamaal Bowman in New York, and more than $8 million to take down Cori Bush in Missouri; both incumbents lost their primaries. But the $4.5 million it spent was not enough to beat Dave Min for Katie Porter’s House seat in California.

Now, the upcoming midterms will likely serve as a test of AIPAC’s strength as lawmakers and voters on both sides of the aisle distance themselves from Israel and its advocates. They will also answer the question of what dividends AIPAC — whose PAC opened the year with a nearly $100 million war chest — will draw if it focuses on punishing candidates who show insufficient support for Israel.

Dorton said he is not concerned. The UDP is looking ahead to the June midterm primaries and will “continue to run ads that move the needle” in primary races about issues that mostly don’t involve Israel, he said. He added that the group is assessing polling data and “candidate viability” for dozens of races around the country — including in NJ-11.

“There is a strong bipartisan pro-Israel majority in Congress,” Dorton said. “And we intend to keep it that way.”

The post AIPAC defends $2.3M spend against ‘pro-Israel’ politician in NJ-11, where anti-Israel candidate is prevailing appeared first on The Forward.

Uncategorized

Oklahoma board denies proposal for Jewish charter school — and lawyers up ahead of expected legal battle

(JTA) — A Jewish group is preparing to sue to overturn a ban on publicly funded religious charter schools in Oklahoma, after a state board unanimously rejected its proposal on Monday.

The Oklahoma Statewide Charter School Board’s decision blocked an application from the National Ben Gamla Jewish Charter School Foundation to open a statewide virtual Jewish school serving grades K-12 beginning next school year.

Ben Gamla’s legal team, led by Becket, a prominent nonprofit religious liberty law firm, said the rejection violates the Constitution’s Free Exercise clause and announced plans to file suit in federal court. In a statement, Becket attorney Eric Baxter criticized Oklahoma Attorney General Gentner Drummond, who has argued that publicly funded religious charter schools are unconstitutional.

“Attorney General Drummond’s attack on religious schools contradicts the Constitution,” Baxter said. “His actions have hung a no-religious-need-apply sign on the state’s charter school program. We’ll soon ask a federal court to protect Ben Gamla’s freedom to serve Sooner families, a right that every other qualified charter school enjoys.”

A victory for Ben Gamla could redraw the line separating church and state, establishing the first school of its kind nationwide and opening the possibility for taxpayer-funded religious schools across the country.

Spearheaded by former Florida Democratic Rep. Peter Deutsch, the Ben Gamla proposal called for a blend of daily Jewish religious studies alongside secular coursework. Deutsch, who nearly two decades ago established a network of nonreligious “English-Hebrew” charter schools in Florida, has said he chose Oklahoma as a testing ground for what he views as a viable model of publicly funded religious education.

In a statement, Deutsch criticized the board’s decision.

“Parents across the Sooner State deserve more high-quality options for their children’s education, not fewer,” Deutsch said in a statement. “Yet Attorney General Drummond is robbing them of more choices by cutting schools like Ben Gamla out. We’re confident this exclusionary rule won’t stand for long.”

The rejection, delivered during the board’s monthly meeting, did not come as a surprise. The board’s 2023 approval of a similar application by a Christian group to establish St. Isidore of Seville Catholic Virtual School was ultimately overturned by the Oklahoma Supreme Court on constitutional grounds.

An attempt to challenge the state court decision at the federal level failed when the U.S. Supreme Court deadlocked on the case last year due to a recusal by Amy Coney Barrett, who has ties to the Catholic group.

Several board members cited the legal outcome in explaining their votes against Ben Gamla.

“I am troubled by the fact that our hands are tied by the state Supreme Court decision, but I think we have to honor it, and it’s a very clear directive,” board member Damon Gardenhire said at the meeting.

Board member David Rutkauskas said it was “very unfortunate” that the board was “bound” by the Oklahoma Supreme Court, adding that the decision was not because Ben Gamla is “not a good candidate or qualified.”

“If I could have voted for this school today without being bound, I would have voted yes,” Rutkauskas said. “I think it would be great for the Jewish community and the Jewish kids to have this option of a high quality school.”

Ahead of the board’s vote, during public comment, Jewish Oklahoma resident Dan Epstein argued that the “public should not be funding sectarian education.”

“My religious education was entirely private,” Epstein said. “My parents didn’t ask for anybody else to pay for it. They paid for it as part of dues to our congregation, and so I’m here today to express my opposition to the application of the Ben Gamla school.”

Epstein was not the only Jewish voice in Oklahoma to object to Ben Gamla.

Last month, the Tulsa Jewish Federation and several local Jewish leaders issued a joint statement in which they criticized Ben Gamla for failing to consult local Jewish leaders ahead of their application to open the school.

“We are deeply concerned that an external Jewish organization would pursue such an initiative in Oklahoma without first engaging in meaningful consultation with the established Oklahoma Jewish community,” the leaders wrote. “Had such a consultation occurred, the applicant would have been made aware that Oklahoma is already home to many Jewish educational opportunities.”

Oklahoma is home to fewer than 9,000 Jews, many of whom live in Tulsa.

During Monday’s deliberation, board member William Pearson cited opposition to the Ben Gamla proposal from Oklahoma Jewish congregations.

“My real concern is that I don’t see a grassroots effort from the Jewish community in the state of Oklahoma,” Pearson said. “Now maybe I’m wrong, but I haven’t seen it. What I have seen is the synagogues, both from Oklahoma City and Tulsa, come out in opposition to this, and I find that very interesting, that the Jewish community, the people that are involved daily in Jewish lifestyle, that they’re opposed to this.”

Immediately after voting to turn down Ben Gamla, the board approved hiring outside legal counsel in anticipation of a lawsuit.

“I can’t predict the future, but I would say, by all indicators, I would be shocked if there’s not a lawsuit filed by Friday,” board chair Brian Shellem said.

The post Oklahoma board denies proposal for Jewish charter school — and lawyers up ahead of expected legal battle appeared first on The Forward.

Uncategorized

Anne Frank and ‘Night’ may soon be required reading in Texas public schools. Is that good for the Jews?

(JTA) — In the years since school libraries became a culture-war flashpoint, Texas has been one of the most active states to pull books from shelves in response to parental complaints — sometimes including versions of Anne Frank’s diary and other Jewish books.

Now, Texas is pursuing a new approach: requiring that Frank’s diary, and several other Jewish texts, be taught throughout the state.

The Texas state education board recently discussed draft legislation that would create the nation’s first-ever statewide K-12 required reading list for public schools. Among the roughly 300 texts on the list: Elie Wiesel’s Holocaust memoir “Night”; Lois Lowry’s young-reader Holocaust novel “Number the Stars”; George Washington’s letter to a Rhode Island synagogue in 1790, and Frank’s diary — the “original edition.”

Each of the works could become mandatory reading for Texas’s 5.5 million schoolchildren as soon as the 2030-31 school year, as the state’s conservative education leaders seek to reverse a nationwide decline in the number of books read or assigned in class while also constraining the texts that activist parents tend to object to. Instead of letting individual teachers put together reading lists that might include “divisive” or progressive content, Republicans in Texas are trying to nudge the curriculum toward a “classical education” said to draw on the Western canon.

Supporters said the list would help ensure every student is on the same page.

“We want to create an opportunity for a shared body of knowledge for all the students across the state of Texas,” Shannon Trejo, deputy commissioner of programs for the Texas Education Agency, told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency about why the group undertook the list project.

While state lawmakers passed a law mandating at least one required book per grade, the board has decided to implement a full reading list. Trejo said the options had been whittled down from thousands of titles suggested in a statewide teachers survey. They were also cross-referenced with a variety of other sources, including books from “high-performing educational systems” in other states and reading lists from the high-IQ society Mensa.

“We’re trying to help students love reading again,” LJ Francis, a Republican member of the state school board who supports the list, said during the Jan. 28 meeting. “I personally think schools should be teaching more than what we have on this list.”

The proposal underscores a complicated moment for Jewish literature in Texas schools, where books about the Holocaust and Jewish history have recently been pulled from shelves amid parental complaints but are now poised to become required reading statewide. Jewish educators and free-speech advocates say the shift reflects both recognition of Holocaust education’s importance — and continuing tensions over who controls what students read and how those stories are taught.

The overall list largely centers the Western canon and deemphasizes modern works as well as most books about race and identity, although selections from Booker T. Washington, Frederick Douglass and other Black American authors made the cut. The Bible is also heavily represented, with selections from both the Old and New Testaments on the reading list.

The state’s Holocaust Remembrance Week education mandate means that Jews are one of the few ethnic groups whose stories are fairly well represented on the state’s required reading list. That doesn’t mean that Holocaust educators are unreservedly enthusiastic about the new approach.

“Obviously I’m pleased that they’re including quality Holocaust materials,” Deborah Lauter, executive director of TOLI, the Olga Lenkyel Institute for Holocaust Studies, told JTA. Lauter noted that many teachers trained by TOLI on how to teach the Holocaust in their classrooms — including in Texas — already rely on books that made the list.

But, Lauter said, teachers generally like to develop their own curricula to tailor to their classrooms. “Mandating certain books, I don’t know how teachers would feel about that,” she said.

Lauter also expressed concern about whether the state would be providing materials to help teachers decode the Holocaust texts for their students. Trejo told JTA that fell beyond the scope of the list and the statute.

“It is just the title that is going into the standards for the state of Texas,” Trejo said. “Beyond that, it would be up to publishers to look to, how can I support districts and teachers in teaching this title?”

To literacy activists in the state, the approach was concerning.

“This is censorship as well,” Laney Hawes, co-director of the Texas Freedom to Read Project, told JTA. The overall list, she said, reflects “a very narrow worldview,” and the large number of books on the list would make it difficult for educators to find time for additional texts of their own choosing in class.

At the same time, Hawes said, “there are some really worthwhile books on this list. ‘The Diary of Anne Frank’ is an incredible book.”

The Jewish titles, Trejo said, were selected with additional input from Holocaust museum experts, local rabbis and Jewish day schools in the state. They also sought input from the Texas Holocaust, Genocide, and Antisemitism Advisory Commission.

“We were invited to provide input regarding a few specific parts of these proposals,” Joy Nathan, the commission’s director, told JTA in an email.

She named “Blessed Is the Match,” a poem by the Hungarian-born poet and resistance fighter Hannah Senesh, as a reading that her commission recommended for the draft list. “We will continue these direct conversations throughout the process.”

At the state education board meeting, a last-minute amendment proposed by the board’s GOP treasurer sought to remove dozens of works from the list, including Senesh’s poem and Washington’s letter.

The amendment would replace those texts with a new crop of selections, including “Refugee,” a young-adult novel by Alan Gratz that partially follows a German Jewish World War II refugee; Biblical passages on Moses; Maurice Sendak’s “Where the Wild Things Are”; George Orwell’s “1984”; and a book about former Polish president Lech Walesa. The amendment also listed “Night” as required in two different grades.

The story of Moses, the board member said, made the amendment’s cut because “there are a lot of parallels between Moses leading the people out of Egypt and the American Revolution.” Debate on the topic dragged into the night, with board members arguing whether requiring Bible passages would violate the Establishment clause and which Biblical translation had superior literary merit.

Following the amendment, the board agreed to postpone a vote on the required books until April to give members time to review both lists. Another board member, pushing for greater racial diversity in the list, submitted his own titles for review as well.

Once voted on, the legislation would enter a public comment period prior to being formally adopted at a later meeting.

A long list of public commenters at the meeting opposed the law on various grounds, including that it was overly prescriptive, lacked proper balance between classical and modern literature, included more books than could realistically be taught, overly emphasized Christian texts over other religious works, and lacked racial and gender diversity. One teacher said that “Night” is traditionally taught at a different grade level than the law mandates.

Among those who testified against the policy was Rebecca Bendheim, a middle-school teacher at an Austin private school and author of young-adult novels about Jewish and LGBTQ identity. “I believe the list underestimates what Texas students can do,” Bendheim said.

A handful of commenters voiced support for the measure. Matthew McCormick, education director at the conservative Texas Public Policy Foundation, which backed the law, said that it covers “important historical eras such as the Great Depression and the Holocaust.”

He added, “By approving this reading list, the board has the opportunity to enact a generational change by ensuring that every public school student has a strong foundation in literacy and literature.”

At Wednesday’s meeting, the board also voted on new required civics training for teachers and new required vocabulary lists, which would be extracted from the required books.

The state’s embrace of Jewish curricula comes after one Texas school district recently pulled “The Devil’s Arithmetic,” another young-reader Holocaust novel, following a “DEI content” weeding process aided by artificial intelligence. A state law currently on the books in Texas places classroom restrictions on “instruction, diversity, equity and inclusion duties, and social transitioning.”

While Jewish texts are generously represented on Texas’s list, works by and about authors of other identities are not; the high school list, for example, features no Hispanic authors. An estimated 245,000 Jews live in Texas, or less than 1% of the population, according to Brandeis University demographics; Hispanics, by contrast, form 40% of the state population, more than the white share.

The state offered lists of approved Holocaust materials teachers may select from when marking Holocaust Remembrance Week last month. Those approved materials, provided by the Texas Holocaust, Genocide, and Antisemitism Advisory Commission, include many of the texts now required in the legislation.

The proposed legislation concerns activists in the state who oppose book bans and restrictions on students’ “right to read.” Hawes, a Fort Worth mother of four children in the state education system, first became an activist after her district removed the “Graphic Adaptation” of Frank’s diary from its shelves in 2022.

That district returned the book after public outcry. But other districts both in and outside of Texas followed suit by pulling the same edition, along with other Jewish books including “Maus” and “The Fixer,” over the last few years.

Seeing Frank’s diary on the state’s required reading list now, Hawes said, “feels weird to me.”

She noted that the draft legislation specifies that the “original edition” must be taught. The 2018 illustrated adaptation, which includes a passage of Frank discussing a same-sex attraction that had been excised from the original published edition, has been opposed by conservative parents across the country.

In a slideshow by the Texas Educational Agency that outlines the proposed requirements, Frank’s diary is portrayed as an “anchor” text for the 7th grade. “Blessed Is the Match,” an ode to self-sacrifice for a higher cause, and Washington’s letter, a landmark statement of religious tolerance, are listed as supplemental texts for the diary.

The goals of the unit, the agency states, are “factual accounts of Jewish resistance during the Holocaust” and “foundational American ideals of religious liberty and tolerance.”

The Biblical passages, the agency notes, are intended to fulfill a statewide requirement that school districts have “an enrichment curriculum that includes: religious literature, including the Hebrew Scriptures (Old Testament) and New Testament, and its impact on history and literature.” Christian activist groups within Texas, and several elected officials, have pushed for years to promote Evangelical Christian texts in public schools.

The inclusion of Washington’s letter, which assures the Newport congregation that Jews will find safe haven in the United States, also struck Hawes as suspicious. The list contains numerous texts promoting patriotism but does not include any material addressing ongoing antisemitism in America.

“This is making us think that George Washington solved antisemitism. And he didn’t,” she said.

Lauter said that if Texas’s policy of statewide Holocaust book requirements becomes a broader trend, she would welcome it — despite her concerns.

“I think it’s a positive. We support more Holocaust education in schools,” she said. “It’s certainly better than the opposite, which is banning books.”

The post Anne Frank and ‘Night’ may soon be required reading in Texas public schools. Is that good for the Jews? appeared first on The Forward.