Uncategorized

The ‘iconic’ Jewish foods that make New York New York

(New York Jewish Week) — In 2004, June Hersh and her family sold the Bronx-based lighting business that her father founded almost 50 years earlier. Hersh, along with her mother, sister and their husbands, all worked there. The day of the sale, her sister, Andrea Greene, turned to Hersh and said: “We did well! Now, let’s do good.”

Greene, a breast cancer survivor, became a volunteer for the Israel Cancer Research Fund. Hersh, who was 48 at the time, asked herself what her “good” would be — she loved to cook, and she loved to write.

A couple of years later, she approached David Marwell, then the director of The Museum of Jewish Heritage–A Living Memorial to the Holocaust, offering to write a cookbook to benefit the museum. In it, she would tell the stories and recreate the recipes of museum members who were Holocaust survivors. The book, “Recipes Remembered, A Celebration of Survival” was published in 2011. To date, 25,000 copies of the book have been sold to benefit the museum as well as other Jewish organizations.

Since then, Hersh has written several other books with a philanthropic component, including “The Kosher Carnivore: The Ultimate Meat and Poultry Cookbook,” which benefited Mazon, a Jewish nonprofit working to combat hunger, and “Still Here: Inspiration from Survivors and Liberators of the Holocaust” with proceeds donated to Selfhelp, a social services agency aiding Holocaust survivors and the elderly in the New York metropolitan area.

This month, her fifth book, “Iconic New York Jewish Food,” was published, benefitting Met Council, a New York-based Jewish charity serving more than 315,000 needy people each year. As Met Council CEO David Greenfield writes in the book’s foreword, the organization operates “the largest emergency food system in America, focused on helping individuals and families who maintain kosher diets, as well as other religiously informed dietary practices.”

Hersh said was moved by Met Council’s inclusivity. “I don’t think Jewish organizations ever help only Jewish people,” she told the New York Jewish Week. “They always have a broad reach, and I am proud of that.”

In “Iconic New York Jewish Foods,” Hersh writes about Jewish foods that have, over time, become New York foods: bagels, egg creams, cheesecake, hot dogs and much more. The book combines humor (one chapter is titled: “Doesn’t That Look Appetizing: The Birth of a New York Phenomenon”), history (the evolution of the hot dog bun, for example) and recipes (like “Mash Up Hash Up Latkes,” potato pancakes made with corned beef and pastrami).

Hersh spoke with the New York Jewish Week about her book, what makes a Jewish food iconic, and what’s special about New York City.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

New York Jewish Week: What inspired you to write a book about iconic New York Jewish foods?

June Hersh: In the world of food, I have two passions. One is to tell the history of food. What is its lineage? How did it come to be? Who first ate it? Why is it important? My second passion is preserving the food memory of the Jewish people. I don’t think anything binds us together like food. It is the connective thread in the Jewish story.

What makes a food Jewish?

Most Jewish food is not easy to define. For Ruth Kohn, a Jewish refugee from Germany, arroz con pollo became a Jewish food that she made in her new home in Sosua, Dominican Republic. If you are looking for Jewish food, throw a dart on a map. Wherever it lands, you will find someone making Jewish food. It might not be the Jewish food we identify with, but it is Jewish food. It is informed by something in one’s heritage and culture — where the makers of it left or where they landed.

My grandmother was from the island of Rhodes. Her family came from Spain, and she spoke Ladino. Her food was informed by the Spanish techniques of her family and the Greek influences of the country where they landed after their expulsion from Spain.

Given your Sephardic background, why is the focus of the book on Ashkenazi foods?

Ashkenazi, Eastern European food is what informed the Jewish foodways of New York. The only iconic Sephardic food [in New York] is Turkish taffy which was introduced here by Herman Herer from Austria and Albert Bonomo, from Turkey.

What makes a Jewish food iconic?

A Jewish food becomes iconic when it is prevalent on menus, and not just in Jewish restaurants. Iconic food is something that has become part of everyone’s food culture.

An example would be New York cheesecake, a food you see on mainstream menus. Cheesecake, according to Alan Rosen, a third-generation proprietor of Junior’s, a Brooklyn restaurant known for it, is one of the most ordered desserts in any restaurant anywhere. And cheesecake didn’t exist in the same form in which it exists now until you had Jewish immigrants.

People eat hot dogs on rolls all the time. You didn’t have hot dogs on rolls until you had Jewish immigrants; that was born out of ingenuity, which is part of what I admire and respect and celebrate in Jewish food.

Can you give some examples of how Jewish food is embraced in NYC at large?

One of the best New York City bagel shops, Absolute Bagels, is run by a Thai baker. One of the best examples of old-school brisket comes from David’s Brisket House, owned by non-Jewish Yemenites. The beauty of the Jewish food of New York is how it is embraced by so many cultures who then give their spin and interpretation.

—

The post The ‘iconic’ Jewish foods that make New York New York appeared first on Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

Uncategorized

Noam Bettan Releases Song ‘Michelle’ He’ll Perform as Israel’s Rep for 2026 Eurovision Song Contest

Noam Bettan in the music video for “Michelle.” Photo: YouTube screenshot

Noam Bettan revealed on Thursday the song he is set to perform when he represents Israel at the 70th Eurovision Song Contest in Vienna, Austria, in May.

“Michelle” is a trilingual song written by Bettan, Nadav Aharoni, Tzlil Klifi, and Yuval Raphael, who represented Israel in last year’s Eurovision and finished in second place. The song features lyrics in Hebrew, English, and French, and premiered during a special broadcast on the Kan public broadcaster.

“‘Michelle’ tells the story of choosing to break free from a toxic emotional cycle. It’s a story about emotional growth and maturity, at the moment when the protagonist realizes they must let go and choose a new path for themselves,” Eurovision stated in its official description of the song.

“Michelle” is largely in Hebrew and French with only one verse in English. “Walking down Florentin/Ocean eyes/Memories/I, I’m losing my mind,” Bettan sings in English. “An angel but it is hell/Trapped in your carousel/Round and round/Under your spell.”

Bettan, who turned 28 on Thursday, was born in Israel and raised in the city of Ra’anana. His parents are French and lived in the French city of Grenoble before immigrating to Israel with their two older sons.

Bettan is fluent in French, Hebrew, and English. He won the Israeli television show and singing competition “HaKokhav HaBa” (“The Rising Star”) in January, which automatically secured him the position of representing Israel at this year’s Eurovision. Bettan will perform “Michelle” during the second half of the first Eurovision semi-final on May 12.

“I’m very proud of the song,” Bettan said in a released statement. “It’s a great privilege to bring such a creation to the Eurovision stage. The song is full of energy and emotion that touches on a wide range of feelings. I feel that ‘Michelle’ will bring us moments of shared joy and pride, and I hope this song can bring a little of that light with it.”

Watch the music video for “Michelle” below.

Uncategorized

‘Tool of the Enemy’: Tucker Carlson Under Fire for Latest Unhinged Rant Blaming Iran War on Chabad

Tucker Carlson speaks on first day of AmericaFest 2025 at the Phoenix Convention Center in Phoenix, Arizona, Dec. 18, 2025. Photo: Charles-McClintock Wilson/ZUMA Press Wire via Reuters Connect

Firebrand podcaster Tucker Carlson, one of the most vocal critics of the US-Israel war against Iran, is now blaming the conflict on the Jewish Chabad-Lubavitch movement, telling listeners of his podcast that the war’s aim is to destroy the Al Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem and rebuild the Jewish temple.

The far-right pundit, who has a history of peddling antisemitic conspiracy theories, alleged in his podcast released Wednesday that Israel started its “global religious war” last Saturday as an excuse to destroy the mosque and the Dome of the Rock on the Al Aqsa compound, referred to by Jews as the Temple Mount, in order to build the Third Jewish Temple.

The site is Judaism’s holiest and the historic location of the First and Second Temples.

“There are key players involved in this war, the one happening tonight, who believe that what we’re seeing on our television screen and on Twitter will usher in a series of events that will begin with the destruction of the Dome of the Rock, Al Aqsa Mosque, and then the rebuilding of the Third Temple,” Carlson said.

“This has been going on a long time in public through, in part, the efforts of a group called Chabad. C-H-A-B-A-D,” Carlson said, spelling out the name of the Orthodox Hasidic religious movement.

“Chabad has been pushing in a pretty subtle way, unless you look carefully, for the reconstruction of the Third Temple,” Carlson said.

As proof, Carlson pointed to photos of Israeli soldiers with patches of an illustration of the Third Temple, claiming — but providing no evidence — that they came from Chabad.

In a social media post from two years ago, soldiers fighting against the Hamas terror group were pictured sporting the patches. The Instagram page belongs to The Temple Institute, an NGO advocating for rebuilding the Third Temple that has no connection with Chabad.

The post was accompanied with the caption: “Hamas made it clear from the start when they named their barbaric attack on Israeli citizens, men, women and children, ‘the al Aqsa flood,’ al Aqsa being the jihadist nomenclature for the Temple Mount.”

“Yes, Iranian-backed Hamas, as well as Iran’s other terror proxies are waging war against Israel, against Jerusalem, against the Holy Temple and all that the Holy Temple stands for: peace, brotherhood, prayer, and love for HaShem’s world,” the post read, using the Hebrew name for God, and ending with the biblical passage promising a “house of prayer for all nations.”

Carlson said that building the Third Temple “is totally anathema to Christianity.”

“Christians have a way of dying disproportionately in these wars, which tells you something about their real motives,” he said.

The Chabad movement, which is headquartered in Brooklyn, New York, is not politically affiliated and is widely known for its welcoming engagement with fellow Jews, with a presence in more than 100 countries.

Chabad spokesperson Yaacov Behrman said Carlson’s claims that Chabad is behind the war amount to “a slanderous lie” and “dangerous blood libel.”

“He is also wrong about the Temple patches. They did not come from Chabad. Had he done even basic research, that would be clear,” he added in a post on X. “Reckless rhetoric like this is dangerous and irresponsible.”

Carlson’s @TuckerCarlson claim about Chabad and the Temple Mount is a slanderous lie. His implication that Chabad is behind the war in Iran is a dangerous blood libel.

Chabad’s focus is on encouraging

mitzvos—good deeds—to bring more goodness into the world and hasten the…— Yaacov Behrman (@ChabadLubavitch) March 5, 2026

Rabbi Jonathan Markovitch, the chief Chabad emissary in Kyiv and rabbi of the Ukrainian capital, said he heard Carlson’s comments while sitting in a shelter in Tel Aviv during missile sirens, after being stranded in Israel by the war.

Calling the comments “nonsense,” he said they were driven neither by “concern for human life or any values,” but by “an ugly interest.”

“While I am sitting here in a shelter because of missiles sent by extremists who prefer destruction and death over caring for their own people, there are those who choose to spread baseless antisemitic accusations,” he told The Algemeiner.

“As Chabad emissaries and as Jews, we try to help every person, in every place in the world,” he added.

The Republican Jewish Coalition denounced Carlson’s remarks as “disgusting” and posted a photo of US President Donald Trump at the Queens gravesite of Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, the late Chabad leader, adding that “President Trump and his administration reject this nonsense.”

Tucker Carlson’s opprobrious comments against Chabad are disgusting.

President Trump and his administration reject this nonsense. https://t.co/7kjRQWjP0z pic.twitter.com/Gxjp0gHEMq

— RJC (@RJC) March 5, 2026

US Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer blasted Carlson’s comments on X, calling them “more abhorrent antisemitism from Tucker Carlson, invoking medieval tropes and ugly conspiracies.”

Rabbi Mordechai Lightstone, Chabad’s social media director, pushed back on Carlson’s claim in a post on X, writing that belief in the Third Temple and the Messianic era is important “not just to Chabad, but to all of Judaism,” and describing it as part of the 13 Principles of Faith codified by the medieval Jewish thinker Maimonides.

“The sum total of the goodness and kindness that each of us do, Jew and non-Jew, usher in an era of world peace, when ‘Nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war anymore,’ where a third Temple ‘be a house of prayer for all nations,’” Lightstone added.

Carlson’s remarks were endorsed by several commentators, including fellow podcaster Candace Owens and former US Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene.

In a post on X, Owens warned followers to pay attention to where Chabad centers were located near them, describing Chabad members as “dangerous” and calling them “a radical sect of mystic occultists that follow the idea of a war messiah.”

Greene shared Carlson’s podcast episode, calling it “incredible.”

Incredible podcast by Tucker Carlson.

Telling the truth is no threat to anyone.

The greater threat is war for heretical lies. https://t.co/Vf1fZ9GjsU— Marjorie Taylor Greene

(@mtgreenee) March 5, 2026

Christian Zionist and longtime Carlson critic Laurie Cardoza-Moore slammed the remarks, saying Carlson was “ignorant of the Bible and all things Christian or Jewish.”

Cardoza-Moore, who is president of the Christian Zionist group Proclaiming Justice to the Nations, said she has worked alongside Chabad rabbis worldwide “to build bridges and understanding between our communities.”

“Tucker is simply rehashing medieval antisemitic conspiracies that led to the death of millions of Jews. He does not speak for America or Christendom. He has become a tool of the enemy,” she told The Algemeiner.

In an interview with The Algemeiner last month, Israeli Christian leader Shadi Khalloul accused the former Fox News host of “destroying Christian-Jewish relations” all over the world and “endangering the persecuted Christian community in the Middle East” by falsely portraying Israel as hostile to Christianity.

Carlson has ramped up his anti-Israel content over the last year, according to a study released in December by the Jewish People Policy Institute (JPPI), which tracked the prominent far-right podcaster’s disproportionate emphasis on attacking the Jewish state in 2025.

In September, for example, the podcaster appeared to blame the Jewish people for the crucifixion of Jesus and suggest Israel was behind the assassination of American conservative activist Charlie Kirk.

In a recent episode in which he interviewed US Ambassador to Israel Mike Huckabee, Carlson insisted that Israelis should be subject to genetic tests to determine any ties to the land of Israel.

Uncategorized

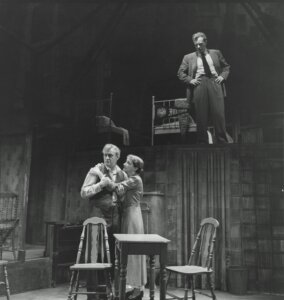

As ‘Death of a Salesman’ returns to Broadway, the question remains — how Jewish is Willy Loman?

Arthur Miller’s 1949 play Death of a Salesman, currently on Broadway in a new production starring Nathan Lane as Willy Loman, was inspired by an uncle of Miller’s and a suicidal colleague of his father’s, both Jewish salesmen.

On the play’s 50th anniversary, Miller told an interviewer that Willy Loman and his family were indeed intended to be Jews. But, he added, they were oblivious to this identity since in postwar America, the Lomans were “light-years away from religion or a community that might have fostered Jewish identity.”

More to the point, in 1947, Miller had lectured at the Committee of Jewish Writers, Artists, and Scientists about a possible new Jewish literary movement in America. After the success of Focus, his 1945 novel about antisemitism, Miller opined: “Jewish artists and writers have it as their duty to address themselves in their works to Jewish themes, Jewish history and contemporary Jewish life.”

Yet despite this belief, Miller proceeded to explain that the Holocaust had temporarily made it impossible for him to write about Jewish life without being “defensive and combative” or to treat Jewish themes “in relation to antisemitism.” A delusional failure, Loman was no role model in his professional or family life, and presenting him as a Jew might have fed already-burgeoning antisemitism among audiences.

Miller would return to Yiddishkeit in his later plays After the Fall (1964); Incident at Vichy (1965); The Price (1968); Playing for Time (1980); and Broken Glass (1994), but Salesman reflected a cagier ethnic identity.

Even so, alert audiences picked up on Yiddishisms or Brooklyn Jewish inflections, such as when Loman’s wife Linda says: “Attention, attention must be finally paid to such a person.”

The literary critic Leslie Fiedler deemed these echoes of Yiddishkeit a symptom of Miller’s being “devious” in creating “crypto-Jewish characters” who are presented instead as generic Americans, supposedly to appeal to a wider American audience.

In a 1998 essay, the playwright David Mamet alleged that by not overtly dwelling on the characters’ Judaism in Salesman, Miller had shortchanged Jewish culture; the play is the “story of a Jew told by a Jew,” he wrote, but Loman’s fate is “never avowed as a Jewish story, and so a great contribution to Jewish American history is lost.”

To which Miller politely retorted that Mamet had discerned the Jewish content in the play, “so it couldn’t have been lost. I mean, what more could anyone want?”

What some observers wanted was a literal embrace of Jewish tradition, which they received when the Yiddish stage actor Joseph Buloff, best remembered for his role as a peddler in the Broadway premiere of the musical Oklahoma! and as a Russian agent in the 1957 MGM musical film Silk Stockings. In 1951, Buloff translated and staged Salesman in Yiddish, a version which has since been revived and performed widely.

The plangent tone of the Yiddish “Toyt fun a Salesman,” made it an audience pleaser, and the literary critic Harold Bloom, a native Yiddish speaker, considered the Buloff translation the “most satisfactory performance” he ever saw of Salesman.

Less internationally celebrated was a contemporaneous staging by The Habima Theatre, the national theater of Israel. Directed by the Czech Jewish theatrical maestro Julius Gellner, it starred a powerhouse cast led by Aharon Meskin, an acclaimed Othello, Golem, and Shylock. Linda Loman was played by Hanna Rovina, who was known as the First Lady of Hebrew Theater; she had previously appeared with Meskin in the Habima production of S. Ansky’s The Dybbuk, and their exalted, visionary scope suited the epic, oneiric moments in Salesman.

Yet Israeli audiences seemed to prefer Miller’s All My Sons to Salesman, reportedly because Loman was a schmendrick, a small-time loser, and his pathetic demise excluded him as an appropriate hero/martyr for the new Jewish state.

Unlike the tearful Yiddish-language Loman and exalted, mythical Hebrew version, both of which glorified Jewish identity, the original Broadway cast was more ambiguous. Loman was played by Lee J. Cobb (born Leo Jacoby) a bellowing bulvan of a performer whose one-note paroxysm riveted audiences with its grim weight. In a televised interview (see the 5-minute mark), the Jewish performer Zero Mostel later complained that even a failed salesman needed humorous charm, entirely missing from the doom-laden Cobb rendition.

Of course, Mostel had suffered during the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) hearings in Washington, DC, at which Cobb and the Salesman stage director Elia Kazan were friendly witnesses, naming names of former friends to placate the government witch hunt, just a few years after Salesman premiered.

By contrast, Miller himself courageously confronted the HUAC and refused to yield to threats, winning admiration even from Jewish critics who did not always laud his work. To celebrate Miller’s 87th birthday, the sometimes waspish Robert Brustein proclaimed the playwright a “true public intellectual” who created “powerful plays, but also a shining moral example unmatched in American theater.”

This praise refutes decades of obloquy, often from fellow Jewish writers, some of whom oddly resented Miller for being married for a few years to Marilyn Monroe, who converted to Judaism before their wedding. Such personal attacks, like Loman, Miller and the play itself, now belong to the ages.

Miller’s play has also won applause for productions with African-American and international casts, including a celebrated staging in Beijing, which resulted in a book and documentary film on the topic. Miller, who traveled to China for the production, explained that the play’s filial theme was as poignant in Chinese tradition as it is for Jews. Indeed, Salesman in China, a 2024 Canadian play by Leanna Brodie and Jovanni Sy freshly revisits that historic production.

As the literary historian Leah Garrett has noted, Willy Loman and Salesman can be simultaneously Jewish and universal. Some theatergoers believe that the finest modern interpretation of the role was performed by Warren Mitchell, an English Jewish actor whose Loman at times sounded vaguely like the Jewish comedian George Burns (born Nathan Birnbaum).

The most powerful, yet nuanced, Loman I ever saw onstage was incarnated by a non-Jewish actor, George C. Scott, who had previously played the role of the biblical patriarch Abraham in the 1966 epic film The Bible: In the Beginning… After a Loman tirade just before intermission, the house lights went up and the audience at New York’s Circle in the Square Theater sat in stunned silence, riveted. The impact resembled that of a 1950 Berlin production at which the audience refused to leave the theater after the show was over.

This immense force of Miller’s play is not always conveyed on stage or screen, even when accomplished actors like Dustin Hoffman and Brian Dennehy have played Loman. But the drama’s inherent force shows how the play has survived triumphantly as an American Jewish literary achievement.

The post As ‘Death of a Salesman’ returns to Broadway, the question remains — how Jewish is Willy Loman? appeared first on The Forward.