Features

New book by noted art expert Celia Rabinovitch explores many themes

By SIMONE COHEN SCOTT

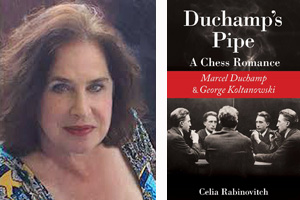

I first began to write this piece as a review of Celia Rabinovitch’s recently launched book “Duchamp’s Pipe, A Chess Romance”, but it turned out to be much more than a book review.

Celia, if you didn’t know, is a Winnipegger and, ever since we first met, I have thought her to be one of the city’s best kept secrets. She is an internationally known artist, cultural historian, author, educator, scholar, and speaker, and except for some slight exposure here in reent years – speaking at the Rady JCC and at the Remis Forum, she keeps a very low profile in her charming River Heights bungalow.

During the years 2002-2008 Celia was professor and director of the School of Art at the University of Manitoba. Her works have been exhibited at the Winnipeg Art Gallery and at the Plug In Gallery in Winnipeg. Elsewhere in Canada Celia has staged exhibitions at the Emily Carr Gallery of Art and Design and, in 2016, at the University of Victoria, where she was artist in residence. She has had broad exposure in Europe and the United States as well – exhibiting, teaching, and lecturing – in Florence, Vienna, New York, California, Cleveland, and Colorado. Her PhD, from McGill University, was on the history of religions and art history.

We first met in Israel, where she had been invited to give a seminar and lecture at the Israel Museum on components of the surrealism exhibit being held there.

Now – about the book: A number of years back Celia was asked to authenticate the provenance of a smoker’s pipe that had been given by renowned modern artist Marcel Duchamp to Grand Master of Blindfold Chess George Koltanowski who, in turn, had given it much later to Nikki Lastreto, his editor at the San Francisco Chronicle.

Celia’s research skills in the art world are well known, and tracking the path of the spiritual connection through the lives of two men, a game, and an artifact, from the late 19th century, when Duchamp learned to play chess, through to the early 21st century, when the pipe was sold at auction, was right up her alley.

She was able to establish that the pipe did indeed belong to Duchamp, and as such it was sold at auction by Christie’s New York for $87,500 US on the 21st of May 2016 – quite a windfall for Nikki Lastreto.

Celia’s detective work became the matrix for this book. She traces several elements throughout the saga – the two men of course, whose principle pastime was playing chess, but also the nature of the game as an entity in itself, the act of pipe-smoking as another, and time – the thread that weaves the story together.

In the author’s hands, time is not chronological. Celia weaves her story forward and backward as she develops her theme and explores each facet of the ethereal relationship between people and objects. Not to worry, though, because she thoughtfully provides a time-line in the back pages for readers who might like to sort things out.

The story becomes a beautifully written history book of sorts, as the atmosphere of the surrealism period of modern art begins to permeate the senses. It was a time, pre WWI, when certain groups of artists wished to jar the sensibilities of people living in what has since been referred to as “the age of innocence”.

The work that brought Duchamp to worldwide attention was his then shocking painting, ‘Nude Descending a Staircase’, which he entered in the Armory Show in New York in 1913. Later, he became even bolder, positioning a urinal in a photograph and calling it a fountain. (Dada art takes getting used to. Personally, I’m saddened that the artist’s inclination to shock the bourgeoisie has drawn attention away from the skilled painter and original colourist that he was.)

George Koltanowski, International Master of Chess, and Honorary Grand Master, was giving chess exhibitions in Guatemala and Havana, Cuba when the Nazis invaded Belgium. His family in Antwerp, including his mother and his brother, Harry, perished in the Holocaust. The U.S. Consul in Cuba offered him a U.S. visa. George could play chess while blindfolded – and win. He had, he said, a “phonographic memory”, and remembered, once told, what was in each and every square on the chessboard. He made his living at chess, both by playing in exhibits and tournaments all over the world, also by promoting tournaments and chess clubs himself, lecturing, and writing. His column in the San Francisco Chronicle ran for 56 years. In 1986 he was inducted into the U.S. Chess Hall of Fame.

The game itself is another character in this blend of personalities. Chess is comprised of so many exquisitely fascinating features: its age, its forms, and the hypnotic involvement it seems to provoke (all right – call it addictive). Chess clubs were popping up everywhere in that day, some even founded by Duchamp and Koltanowski. Every city they happened to visit needed a venue where they could find partners, although Koltanowski was known to have played against a machine – even an elephant (Ed. note: I din’t know elephants could play chess. Who won the game, Simone?)

Duchamp became obsessed with the game, all but giving up his vocation. He created several sets of chess pieces, which sold successfully . (Although from a well-heeled family, he needed to scrounge for a living like everyone else in Greenwich Village.)

Chess pieces are objets d’art in their own right, but one can also appreciate the artistry that goes into the design of a pipe. A smoker’s pleasure comes from the shape and material – the heft if you like, of the pipe, as much as from the tobacco a smoker uses.

The specific pipe that is the star of the book is a rather chunky, boxy, artifact. It must have been one that Duchamp particularly liked because the author describes the giving of it to George as a gesture of regard, meant to mark the former’s appreciation of their friendship.

If this book were a book club choice, there would be terrific areas for discussion. Every aspect, the times they played chess together, other encounters and journal entries on the part of these two men and their friends, give such nuanced glimpses of character and personality. Chess is – remember, a game of thinking and strategy, although smoking was often a complement to chess in the past: Smoking while studying the board, smoking while visualizing moves, smoking, thinking, imagining, and finally just smoking.

Meanwhile, life, including two world wars, was whipping around the two main protagaonists in the book. Celia has a previous book (2002) entitled “Surrealism and the Sacred: Power, Eros, and the Occult in Modern Art”. That information is important to bear in mind because of the mystic quality the author perceives between people and objects and time, in other words, in existence.

Another Winnipegger, Irwin Lipnowski, has an essay towards the end of this book. Irwin, as we know, is a chess champion in his own right. Here, he speculates on the future of chess cafés in an era subsumed by technology.

Something else interesting about chess: As the Parshas on the last couple of Shabbats were about the naming of Beersheva, I decided to look up that Israeli city on line. Here’s what I came upon, from an article written in October, 2009: “With eight Chess Grand Masters calling Beersheva home, the city has more International Grand Masters per capita than any other city in the world.” Hmm!

“Duchamp’s Pipe, A Chess Romance” was launched via Zoom on November 19th, to an international audience. Celia spoke about her experiences writing the book with Ann McCoy, an artist and writer herself, and their conversation is now on YouTube – a worthwhile watch.

“Duchamp’s Pipe: A Chess Romance”

By Celia Rabinovitch

Published by Pengin Random House, 2020

256 pages

Features

The Tech That Never Sleeps: Inside the Always-On Engines of No Limit Casinos

In communities across Canada, including Winnipeg’s dynamic Jewish community, technology has become an integral part of daily life, whether through synagogue livestreams, local cultural programming, or real-time coverage of global events affecting Israel and the diaspora. Modern digital infrastructure, while often unseen to the public, runs continuously behind the scenes, enabling information networks that never stop. The same notion of ongoing connectivity drives the 24-hour digital entertainment platforms.

One example of this infrastructure is seen in online gaming settings, where real-time data systems enable experiences that are meant to run without interruption. The global online gambling industry is expected to increase from around $97.9 billion in 2026, with internet penetration and mobile connectivity continuing to climb globally. As a result, readers interested in how these platforms work often consult a comprehensive list of No Limit casino platforms to gain a better understanding of the ecosystem.

While conversations about casinos sometimes center on the games themselves, what’s underneath the narrative is technical. Behind every digital table or interactive game is a network of servers, verification tools, live data processors, and uptime monitoring systems that must run continually. Unlike traditional venues that close at night, online platforms rely on always-on design, which means that their software infrastructure must run 24 hours a day, seven days a week, independent of player time zones.

Infrastructure That Never Closes

Although Winnipeg readers may be more familiar with the servers that power newsrooms, streaming services, and community websites, the technology center of global platforms shares similar concepts. Modern digital systems rely significantly on distributed cloud computing, which means that data is handled simultaneously over several geographical locations rather than in a single location.

This layout increases credibility while also allowing platforms to run consistently even when millions of people are actively accessing the system. Similarly, big cloud providers operate worldwide networks of data centers capable of providing near-constant uptime. According to reliability measures released by major cloud providers, such as Google Cloud infrastructure reliability overview, modern corporate systems typically aim for uptime levels greater than 99.9 percent.

That figure may sound abstract, yet it corresponds to only a few minutes of disturbance every month. In fact, ensuring such regularity needs sophisticated monitoring systems that identify faults immediately, quickly divert traffic, and maintain redundant backups across different continents. Unlike early internet platforms, which relied on a single server room, today’s large-scale systems function as interconnected worldwide networks.

Real-Time Data: The Pulse of Modern Platforms

While infrastructure keeps systems operating, real-time data engines guarantee that information is constantly sent between users and servers. These systems handle massive amounts of data per second, including player activities, system status updates, and verification checks. Although the public rarely observes these operations, they are the digital pulse of today’s internet platforms.

Real-time computing has also revolutionized industries known to Canadian readers. Financial markets, for example, use comparable high-speed data processing to quickly update stock values across trading platforms. The same logic applies to global logistical networks, airline scheduling systems, and even newsrooms that monitor breaking news as it occurs.

This is essentially one of the distinguishing features of modern digital infrastructure: information no longer moves in batches, but rather continuously over high-capacity data pipelines. Regardless of how complicated these systems are, they must stay reliable and safe, which is why developers invest much in automated monitoring and predictive maintenance.

Security and Verification in the Always-On Era

Technology that never sleeps must also be self-verifying. Modern digital platforms use multilayer security systems to identify suspicious conduct, validate user identities, and safeguard critical data. Many of these procedures remain in the background, but they are extremely important for preserving confidence in online services.

Unlike older internet platforms, which depended heavily on passwords, newer systems often include behavioral analytics, device identification, and automatic danger detection. These technologies work silently, yet they examine patterns in real time, detecting unacceptable behavior before it spreads throughout a network.

The larger IT sector has made significant investments in these measures. Organizations such as the National Institute of Standards and Technology cybersecurity framework overview give guidelines for software developers throughout the world in designing resilient digital systems. Similarly, academic research from universities continues to investigate how internet infrastructure can stay safe while yet allowing for large-scale connectivity.

Lessons for the Wider Digital World

Although talks regarding entertainment platforms often focus on user experiences, the underlying technology symbolizes a larger revolution in the digital economy. Today’s online systems must run constantly, expand fast, and stay safe even under high demand. While normal user may only observe the automatic interface on their screen, the real story is the engineering it takes to maintain that experience.

While technology develops very quickly, one thing remains constant: systems meant to function indefinitely need both intelligent engineering and meticulous management. Despite their complexity, these digital engines have become the silent basis for modern life, powering everything from local news websites to global platforms that never sleep.

Features

ClarityCheck: Securing Communication for Authors and Digital Publishers

In the world of digital publishing, communication is the lifeblood of creation. Authors connect with editors, contributors, and collaborators via email and phone calls. Publishers manage submissions, coordinate with freelance teams, and negotiate contracts online.

However, the same digital channels that enable efficient publishing also carry risk. Unknown contacts, fraudulent inquiries, and impersonation attempts can disrupt projects, delay timelines, or compromise sensitive intellectual property.

This is where ClarityCheck becomes a vital tool for authors and digital publishers. By allowing users to verify phone numbers and email addresses, ClarityCheck enhances trust, supports safer collaboration, and minimizes operational risks.

Why Verification Matters in Digital Publishing

Digital publishing involves multiple types of external communication:

- Manuscript submissions

- Editing and proofreading coordination

- Author-publisher negotiations

- Marketing and promotional campaigns

- Collaboration with illustrators and designers

In these workflows, unverified contacts can lead to:

- Scams or fraudulent project offers

- Intellectual property theft

- Miscommunication causing delays

- Financial loss due to fraudulent payments

- Unauthorized sharing of sensitive drafts

Platforms like Reddit feature discussions from authors and freelancers about using verification tools to safeguard their work. This highlights the growing awareness of digital safety in creative industries.

What Is ClarityCheck?

ClarityCheck is an online service that enables users to search for publicly available information associated with phone numbers and email addresses. Its primary goal is to provide additional context about a contact before initiating or continuing communication.

Rather than relying purely on intuition, authors and publishers can access structured information to assess credibility. This proactive approach supports safer project management and protects intellectual property.

You can explore community feedback and discussions about the service here: ClarityCheck

Key Benefits for Authors and Digital Publishers

1. Protecting Manuscript Submissions

Authors often submit manuscripts to multiple editors or publishers. Before sharing full drafts:

- Verify the contact’s legitimacy

- Ensure the communication aligns with known publishing entities

- Reduce risk of unauthorized distribution

A quick lookup can prevent time-consuming disputes and protect original content.

2. Safeguarding Collaborative Projects

Digital publishing frequently involves external contributors such as:

- Illustrators

- Designers

- Editors

- Ghostwriters

Verification ensures all collaborators are trustworthy, minimizing the chance of intellectual property theft or miscommunication.

3. Enhancing Marketing and PR Outreach

Promoting a book or digital publication often involves connecting with:

- Bloggers

- Reviewers

- Book influencers

- Digital media outlets

Before sharing press kits or marketing materials, verifying email addresses or phone contacts adds confidence and prevents potential misuse.

How ClarityCheck Works

While the internal system is proprietary, the user workflow is straightforward and efficient:

| Step | Action | Outcome |

| 1 | Enter phone number or email | Search initiated |

| 2 | Aggregation of publicly available data | Digital footprint analyzed |

| 3 | Report generated | Structured overview presented |

| 4 | Review by user | Informed decision before engagement |

The platform’s simplicity makes it suitable for authors and publishing teams, even those with limited technical expertise.

Integrating ClarityCheck Into Publishing Workflows

Manuscript Submission Process

- Receive submission request

- Verify contact via ClarityCheck

- Confirm identity of editor or publisher

- Share draft or proceed with collaboration

Collaboration with Freelancers

- Initiate project with external contributors

- Run ClarityCheck to verify email or phone number

- Establish project agreement

- Begin content creation safely

Marketing Outreach

- Contact media or reviewers

- Verify digital identity

- Share promotional materials with confidence

Ethical and Privacy Considerations

While ClarityCheck provides useful context, it operates exclusively using publicly accessible information. Authors and publishers should always:

- Respect privacy and data protection regulations

- Use results responsibly

- Combine verification with personal judgment

- Avoid sharing sensitive data with unverified contacts

Responsible use ensures the platform supports security without compromising ethical standards.

Real-World Use Cases in Digital Publishing

Scenario 1: Verifying a New Editor

An author is contacted by an editor claiming to represent a small publishing house. Running a ClarityCheck report confirms the email domain aligns with publicly available information about the company, reducing risk before signing an agreement.

Scenario 2: Screening Freelance Illustrators

A digital publisher seeks an illustrator for a children’s book. Before sharing project details or compensation terms, ClarityCheck verifies contact information, ensuring the artist is legitimate.

Scenario 3: Marketing Outreach Safety

A self-publishing author plans a social media and email campaign. Verifying influencer or reviewer contacts helps prevent marketing materials from reaching fraudulent accounts.

Why Verification Strengthens Publishing Operations

In digital publishing, speed and creativity are essential, but they must be balanced with security:

- Protect intellectual property

- Maintain trust with collaborators

- Ensure financial transactions are secure

- Prevent delays due to miscommunication

Verification tools like ClarityCheck integrate seamlessly, allowing authors and publishing teams to focus on creation rather than risk management.

Final Thoughts

In a world where publishing is increasingly digital and collaborative, verifying contacts is not just prudent — it’s necessary.

ClarityCheck empowers authors, editors, and digital publishing professionals to confidently assess phone numbers and email addresses, protect their intellectual property, and streamline communication.

Whether managing manuscript submissions, coordinating external contributors, or launching marketing campaigns, integrating ClarityCheck into your workflow ensures clarity, safety, and professionalism.

In digital publishing, trust is as important as creativity — and ClarityCheck helps safeguard both.

Features

Israel’s Arab Population Finds Itself in Dire Straits

By HENRY SREBRNIK There has been an epidemic of criminal violence and state neglect in the Arab community of Israel. At least 56 Arab citizens have died since the beginning of this year. Many blame the government for neglecting its Arab population and the police for failing to curb the violence. Arabs make up about a fifth of Israel’s population of 10 million people. But criminal killings within the community have accounted for the vast majority of Israeli homicides in recent years.

Last year, in fact, stands as the deadliest on record for Israel’s Arab community. According to a year-end report by the Center for the Advancement of Security in Arab Society (Ayalef), 252 Arab citizens were murdered in 2025, an increase of roughly 10 percent over the 230 victims recorded in 2024. The report, “Another Year of Eroding Governance and Escalating Crime and Violence in Arab Society: Trends and Data for 2025,” published in December, noted that the toll on women is particularly severe, with 23 Arab women killed, the highest number recorded to date.

Violence has expanded beyond internal criminal disputes, increasingly affecting public spaces and targeting authorities, relatives of assassination targets, and uninvolved bystanders. In mixed Arab-Jewish cities such as Acre, Jaffa, Lod, and Ramla, violence has acquired a political dimension, further eroding the fragile social fabric Israel has worked to sustain.

In the Negev, crime families operate large-scale weapons-smuggling networks, using inexpensive drones to move increasingly advanced arms, including rifles, medium machine guns, and even grenades, from across the borders in Egypt and Jordan. These weapons fuel not only local criminal feuds but also end up with terrorists in the West Bank and even Jerusalem.

Getting weapons across the border used to be dangerous and complex but is now relatively easy. Drones originally used to smuggle drugs over the borders with Egypt and Jordan have evolved into a cheap and effective tool for trafficking weapons in large quantities. The region has been turning into a major infiltration route and has intensified over the past two years, as security attention shifted toward Gaza and the West Bank.

The Negev is not merely a local challenge; it serves as a gateway for crime and terrorism across Israel, including in cities. The weapons flow into mixed Jewish-Arab cities and from there penetrate the West Bank, fueling both organized crime and terrorist activity and blurring the line between them.

The smuggling of weapons into Israel is no longer a marginal criminal phenomenon but an ongoing strategic threat that traces a clear trail: from porous borders with Egypt and Jordan, through drones and increasingly sophisticated smuggling methods, into the heart of criminal networks inside Israel, and in a growing number of cases into lethal terrorist operations. A deal that begins as a profit-driven criminal transaction often ends in a terrorist attack. Israeli police warn that a population flooded with illegal weapons will act unlawfully, the only question being against whom.

The scale of the threat is vast. According to law enforcement estimates, up to 160,000 weapons are smuggled into Israel each year, about 14,000 a month. Some sources estimate that about 100,000 illegal weapons are circulating in the Negev alone.

Israeli cities are feeling this. Acre, with a population of about 50,000, more than 15,000 of them Arab, has seen a rise in violent incidents, including gunfire directed at schools, car bombings, and nationalist attacks. In August 2025, a 16-year-old boy was shot on his way to school, triggering violent protests against the police.

Home to roughly 35,000 Arab residents and 20,000 Jewish residents, Jaffa has seen rising tensions and repeated incidents of violence between Arabs and Jews. In the most recent case, on January 1, 2026, Rabbi Netanel Abitan was attacked while walking along a street, and beaten.

In Lod, a city of roughly 75,000 residents, about half of them Arab, twelve murders were recorded in 2025, a historic high. The city has become a focal point for feuds between crime families. In June 2025, a multi-victim shooting on a central street left two young men dead and five others wounded, including a 12-year-old passerby. Yet the killing of the head of a crime family in 2024 remains unsolved to this day; witnesses present at the scene refused to testify.

The violence also spilled over to Jewish residents: Jewish bystanders were struck by gunfire, state officials were targeted, and cars were bombed near synagogues. Hundreds of Jewish families have left the city amid what the mayor has described as an “atmosphere of war.”

Phenomena that were once largely confined to the Arab sector and Arab towns are spilling into mixed cities and even into predominantly Jewish cities. When violence in mixed cities threatens to undermine overall stability, it becomes a national problem. In Lod and Jaffa, extortion of Jewish-owned businesses by Arab crime families has increased by 25 per cent, according to police data.

Ramla recorded 15 murders in 2025, underscoring the persistence of lethal violence in the city. Many victims have been caught up in cycles of revenge between clans, often beginning with disputes over “honour” and ending in gunfire. Arab residents describe the city as “cursed,” while Jewish residents speak openly about being afraid to leave their homes

Reluctance to report crimes to the authorities is a central factor exacerbating the problem. Fear of retaliation by families or criminal organizations deters victims and their relatives from coming forward, contributing to a clearance rate of less than 15 per cent of all murders. The Ayalef report notes that approximately 70 per cent of witnesses refused to cooperate with police investigations, citing doubts about the state’s ability to provide protection.

Violence in Arab society is not just an Arab sector problem; it poses a direct and serious threat to Israel’s national security. The impact is twofold: on the one hand, a rise in crime that affects the entire population; on the other, the spillover of weapons and criminal activity into terrorism, threatening both internal and regional stability. This phenomenon reached a peak in 2025, with implications that could lead to a third intifada triggered by either a nationalist or criminal incident.

The report suggests that along the Egyptian and Jordanian borders, Israel should adopt a technological and security-focused response: reinforcing border fences with sensors and cameras, conducting aerial patrols to counter drones, and expanding enforcement activity.

This should be accompanied by a reassessment of the rules of engagement along the border area, enabling effective interdiction of smuggling and legal protocols that allow for the arrest and imprisonment of offenders. The report concludes by emphasizing that rising violence in cities, compounded by weapons smuggling in the Negev, is eroding Israel’s internal stability.

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.