RSS

Israeli Hebrew didn’t kill Yiddish. As a new exhibit in NYC shows, it gave it a new place to nest.

(New York Jewish Week) — Just before the end of the second millennium, Ezer Weizman, then president of Israel, visited the University of Cambridge to familiarize himself with the famous collection of medieval Jewish notes known as the Cairo Genizah. President Weizman was introduced to the Regius Professor of Hebrew, who had been allegedly nominated by the Queen of England herself.

Hearing “Hebrew,” the president, who was known as a sákhbak (friendly “bro”), clapped the professor on the shoulder and asked “má nishmà?” — the common Israeli “What’s up?” greeting, which some take to literally mean “what shall we hear?” but which is, in fact, a calque (loan translation) of the Yiddish phrase vos hért zikh, usually pronounced vsértsəkh and literally meaning “what’s heard?”

To Weizman’s astonishment, the distinguished Hebrew professor hadn’t the faintest clue what the president was asking. As an expert of the Old Testament, he wondered whether Weizman was alluding to Deuteronomy 6:4: “Shema Yisrael” (Hear, O Israel). Knowing neither Yiddish, nor Russian (Chto slyshno), Polish (Co słychać), Romanian (Ce se aude) nor Georgian (Ra ismis) — let alone Israeli Revived Hebrew — the professor had no chance whatsoever of guessing the actual meaning (“What’s up?”) of this beautiful, economical expression.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Yiddish and Hebrew were rivals to become the language of the future Jewish state. At first sight, it appears that Hebrew has won and that, after the Holocaust, Yiddish was destined to be spoken almost exclusively by ultra-Orthodox Jews and some eccentric academics. Yet, closer scrutiny challenges this perception. The victorious Hebrew may, after all, be partly Yiddish at heart.

In fact, as the Weizman story suggests, the enigma of Israeli Revived Hebrew requires an exhaustive study of the manifold influence of Yiddish on this “altneulangue” (“Old New Language”), to borrow from the title of the classic novel “Altneuland” (“Old New Land”), written by Theodor Herzl, the visionary of the Jewish state.

Yiddish survives beneath Israeli phonetics, phonology, discourse, syntax, semantics, lexis and even morphology, although traditional and institutional linguists have been most reluctant to admit it. Israeli Revived Hebrew is not “rétsakh Yídish” (Hebrew for “the murder of Yiddish) but rather “Yídish redt zikh” (Yiddish for “Yiddish speaks itself” beneath Israeli Hebrew).

That said, Yiddish had been clearly subject to linguicide (language killing) by three main isms: Nazism, communism and, well, Zionism, mutatis mutandis. Prior to the Holocaust, there were 13 million Yiddish speakers among 17 million Jews worldwide. Approximately 85% of the approximately 6 million Jews murdered in the Holocaust were Yiddish speakers. Yiddish was banned in the Soviet Union in 1948-1955.

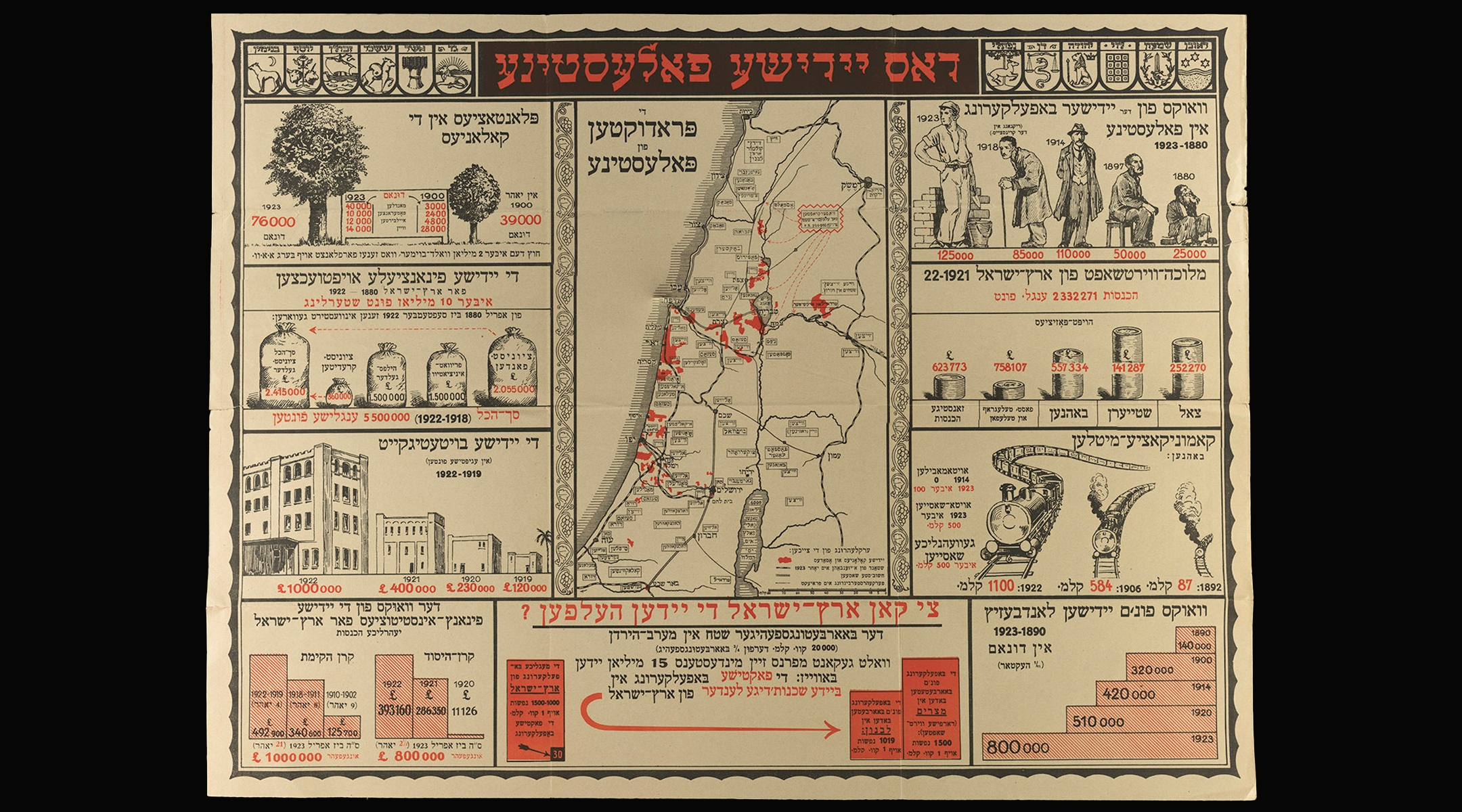

It is high time that a Jewish institution address the issue of Zionism’s attempted linguicide against Yiddish. I am therefore delighted to hear about YIVO mounting a fascinating and multifaceted exhibition in Manhattan titled “Palestinian Yiddish: A Look at Yiddish in the Land of Israel Before 1948,” which opens today. I commend Eddy Portnoy, YIVO’s academic advisor and director of exhibitions, for an exquisite exhibition on a burning issue.

Characterized by the negation of the diaspora (shlilát hagalút) and continuing the disdain for Yiddish generated by the 19th-century Jewish Enlightenment, Zionist ideologues actively persecuted the language. In 1944-5 Rozka Korczak-Marla (1921-1988) was invited to speak at the sixth convention of the Histadrut, General Organization of Workers, in the Land of Israel. Korczak-Marla was a Holocaust survivor, one of the leaders of the Jewish combat organization in the Vilna Ghetto, Abba Kovner’s collaborator, and fighter at the United Partisan Organization (known in Yiddish as Faráynikte Partizáner Organizátsye).

Left, “Di yidishe shtot Tel Aviv” (The Jewish City Tel Aviv), a Yiddish-language guidebook created by Keren Hayesod in Jerusalem, 1933. Right, wounded Yiddishists after an attack by Hebrew language fanatics, Tel Aviv, 1928. Ilustrirte vokh, Warsaw, Nov. 30, 1928. (YIVO Institute for Jewish Research)

She spoke, in her mother tongue Yiddish, about the extermination of Eastern European Jews, a plethora of them Yiddish speakers. Immediately after her speech she was followed on stage by David Ben-Gurion, the first general secretary of the Histadrut, the de facto leader of the Jewish community in Palestine and eventually Israel’s first prime minister. What he said is shocking from today’s perspective:

…זה עתה דיברה פה חברה בשפה זרה וצורמת

ze atá dibrá po khaverá besafá zará vetsorémet…

A comrade has just spoken here in a foreign and cacophonous tongue…

In the 1920s and 1930s, the Battalion for the Defense of the Language (Gdud meginéy hasafá), whose motto was “ivrí, dabér ivrít” (“Hebrew [i.e. Jew], speak Hebrew!), used to tear down signs written in “foreign” languages and disturb Yiddish theater gatherings. However, the members of this group only looked for Yiddish forms (words) rather than patterns in the speech of the Israelis who did choose to speak “Hebrew.” The language defenders would not attack an Israeli Revived Hebrew speaker uttering the aforementioned “má nishmà.”

Astonishingly, even the anthem of the Battalion for the Defense of the Language included a calque from Yiddish: “veál kol mitnagdénu anákhnu metsaftsefím,” literally “and on all our opponents we are whistling,” i.e., “we do not give a damn about our opponents.” “Whistling on” here is a calque of the Yiddish fáyfn af, meaning both “whistling on” and, colloquially, “not giving a damn about” something.

Furthermore, despite the linguistic oppression they suffered, Yiddishists in Palestine continued to produce creative works, a number of which are exhibited by YIVO.

Just like Sharpless, the American consul in Giacomo Puccini’s 1904 opera “Madama Butterfly,” “non ho studiato ornitologia” (“I have not studied ornithology”). I therefore take the liberty of using an ornithological metaphor: On one hand, Israeli Hebrew is a phoenix, rising from the ashes. On the other, it is a cuckoo, laying its egg in the nest of another bird, Yiddish, tricking it to believe that it is its own egg. And yet it also displays the characteristics of a magpie, stealing from Arabic, English and numerous other languages.

Israeli Revived Hebrew is thus a rara avis, an unusual and glorious hybrid.

—

The post Israeli Hebrew didn’t kill Yiddish. As a new exhibit in NYC shows, it gave it a new place to nest. appeared first on Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

RSS

After False Dawns, Gazans Hope Trump Will Force End to Two-Year-Old War

Palestinians walk past a residential building destroyed in previous Israeli strikes, after Hamas agreed to release hostages and accept some other terms in a US plan to end the war, in Nuseirat, central Gaza Strip October 4, 2025. Photo: REUTERS/Mahmoud Issa

Exhausted Palestinians in Gaza clung to hopes on Saturday that US President Donald Trump would keep up pressure on Israel to end a two-year-old war that has killed tens of thousands and displaced the entire population of more than two million.

Hamas’ declaration that it was ready to hand over hostages and accept some terms of Trump’s plan to end the conflict while calling for more talks on several key issues was greeted with relief in the enclave, where most homes are now in ruins.

“It’s happy news, it saves those who are still alive,” said 32-year-old Saoud Qarneyta, reacting to Hamas’ response and Trump’s intervention. “This is enough. Houses have been damaged, everything has been damaged, what is left? Nothing.”

GAZAN RESIDENT HOPES ‘WE WILL BE DONE WITH WARS’

Ismail Zayda, 40, a father of three, displaced from a suburb in northern Gaza City where Israel launched a full-scale ground operation last month, said: “We want President Trump to keep pushing for an end to the war, if this chance is lost, it means that Gaza City will be destroyed by Israel and we might not survive.

“Enough, two years of bombardment, death and starvation. Enough,” he told Reuters on a social media chat.

“God willing this will be the last war. We will hopefully be done with the wars,” said 59-year-old Ali Ahmad, speaking in one of the tented camps where most Palestinians now live.

“We urge all sides not to backtrack. Every day of delay costs lives in Gaza, it is not just time wasted, lives get wasted too,” said Tamer Al-Burai, a Gaza City businessman displaced with members of his family in central Gaza Strip.

After two previous ceasefires — one near the start of the war and another earlier this year — lasted only a few weeks, he said; “I am very optimistic this time, maybe Trump’s seeking to be remembered as a man of peace, will bring us real peace this time.”

RESIDENT WORRIES THAT NETANYAHU WILL ‘SABOTAGE’ DEAL

Some voiced hopes of returning to their homes, but the Israeli military issued a fresh warning to Gazans on Saturday to stay out of Gaza City, describing it as a “dangerous combat zone.”

Gazans have faced previous false dawns during the past two years, when Trump and others declared at several points during on-off negotiations between Hamas, Israel and Arab and US mediators that a deal was close, only for war to rage on.

“Will it happen? Can we trust Trump? Maybe we trust Trump, but will Netanyahu abide this time? He has always sabotaged everything and continued the war. I hope he ends it now,” said Aya, 31, who was displaced with her family to Deir Al-Balah in the central Gaza Strip.

She added: “Maybe there is a chance the war ends at October 7, two years after it began.”

RSS

Mass Rally in Rome on Fourth Day of Italy’s Pro-Palestinian Protests

A Pro-Palestinian demonstrator waves a Palestinian flag during a national protest for Gaza in Rome, Italy, October 4, 2025. Photo: REUTERS/Claudia Greco

Large crowds assembled in central Rome on Saturday for the fourth straight day of protests in Italy since Israel intercepted an international flotilla trying to deliver aid to Gaza, and detained its activists.

People holding banners and Palestinian flags, chanting “Free Palestine” and other slogans, filed past the Colosseum, taking part in a march that organizers hoped would attract at least 1 million people.

“I’m here with a lot of other friends because I think it is important for us all to mobilize individually,” Francesco Galtieri, a 65-year-old musician from Rome, said. “If we don’t all mobilize, then nothing will change.”

Since Israel started blocking the flotilla late on Wednesday, protests have sprung up across Europe and in other parts of the world, but in Italy they have been a daily occurrence, in multiple cities.

On Friday, unions called a general strike in support of the flotilla, with demonstrations across the country that attracted more than 2 million, according to organizers. The interior ministry estimated attendance at around 400,000.

Italy’s right-wing government has been critical of the protests, with Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni suggesting that people would skip work for Gaza just as an excuse for a longer weekend break.

On Saturday, Meloni blamed protesters for insulting graffiti that appeared on a statue of the late Pope John Paul II outside Rome’s main train station, where Pro-Palestinian groups have been holding a protest picket.

“They say they are taking to the streets for peace, but then they insult the memory of a man who was a true defender and builder of peace. A shameful act committed by people blinded by ideology,” she said in a statement.

Israel launched its Gaza offensive after Hamas terrorists staged a cross border attack on October 7, 2023, killing some 1,200 people and taking 251 people hostage.

RSS

Hamas Says It Agrees to Release All Israeli Hostages Under Trump Gaza Plan

Smoke rises during an Israeli military operation in Gaza City, as seen from the central Gaza Strip, October 2, 2025. Photo: REUTERS/Dawoud Abu Alkas

Hamas said on Friday it had agreed to release all Israeli hostages, alive or dead, under the terms of US President Donald Trump’s Gaza proposal, and signaled readiness to immediately enter mediated negotiations to discuss the details.