Features

Booze, Glorious Booze! Bill Wolchock and Prohibition in Manitoba

Ed. introduction: This story was originally published to our website in October, 2023, but it resonated so much with readers – who have continually told me they enjoyed it so much, I’ve decided to bring it back to our Home page every once in a while. It has received an astounding number of views since it was first published – over 10,000 – making it the most popular story ever published on this website.

To explain, last September, I began what turned into an unexpectedly amusing dive into a part of our Jewish community’s history that is endlessly fascinating to me when I wrote about a book that was published in October titled “Jukebox Empire: The Mob and the Dark Side of the Amerian Dream.”

That book is about someone by the name of Wilf Rabin, who was originally Wilf Rabinovitch. Rabin was born in Morden, but moved to Chicago as a young man. Eventually he became involved in the juke box business – a business which was ripe from the outset for exploitation by criminals, especially the Mafia, as juke boxes spun out huge amounts of cash that were never reported to tax authorities.

In the course of writing my article about that book, I mentioned several other Jewish characters who preferred to make their money illegally. I also referred to someone whose name was spelled “Bill Wolchuk” in a book about Winnipeg’s North End, but I made the mistake of saying “Wolchuk” wasn’t Jewish.

Boy, did that unleash a torrent of corrections from readers. It was made quite clear to me that Bill “Wolchock” was very much Jewish – and that he was practically a legend in this town.

Then I received a phone call from reader Arnold Rice, who told me that he had in his possession an article from a December 2, 2002 Winnipeg Free Press about Bill Wolchock. Arnold offered to loan me the article, but I declined, saying I could probably find the article on the Winnipeg Pubic Library digital archives.

That I did – and when I scanned the article, which was written by a former Free Press writer by the name of Bill Redekop, I thought to myself: Here’s the perfect article for our Rosh Hashanah issue: It’s much too long to ever fit into any other issue – and the theme will likely resonate with many of our readers who might consider atoning for their sins on Yom Kippur.

In any event, I was able to get in touch with Bill Redekop and I obtained his permission to reprint the article in full (for a fee, of course). It turns out the article forms a chapter in a book written by Redekop in 2002, titled “Crimes of the Century – Manitoba’s Most Notorious True Crimes.”

I told Redekop that I was actually able to find the book on Amazon – much to his amazement, but that it was also available at several branches of the Winnipeg Public Library. Now, it wasn’t easy transcribing that chapter of Redekop’s book, but I thought it might prove delightful reading for many of our readers.

So, here goes: The story of Manitoba’s greatest bootlegger – Bill Wolchock – someone whose success was on a par with that other great Jewish bootlegging family: the Bronfmans. (Wolchock, however, liked bootlegging so much that he turned down the opportunity to go straight, unlike the Bronfmans. Can you just imagine how much the Combined Jewish Appeal could have benefited from a “straight” Bill Wolchock? And what of all the buildings that would have been named after him – and honours he would have received from our Jewish community, if he had only decided to emulate the Bronfmans?)

A pair of employees talking on the floor of the CNR shops in Transcona sounds like an unlikely launch to the biggest bootleg operation in Manitoba history.

It was the early 1920s under Prohibition. Leonard Wolchock, 74 son of bootlegger, Bill Wolchock, tells the story.

“Sonny (nickname), a CNR boilermaker one day came up to my dad, who was a machinist with the railway and asked if he could make a part for him. “What’s it for?” my dad asked. “It’s for a still,” Sonny said. Sonny was making stills for farmers out in the country. My dad said, “Sonny, you want to make a still? I’ll make you a still and we’re not going to fool around!”

What began as a still to make a little booze for themselves and friends during Canada’s Prohibition certain soon turned into something much bigger. The two CNR workers realized there was an insatiable thirst for their product. “I don’t think dad planned to be in the business for a long time. It was just going good,” said Leonard.

“Before you know it, my dad was making big booze. He could knock out almost 1000 gallons a day. He wasn’t one of these Mickey Mouse guys making 10 gallons like in the country, like in Libau and all these places. And as time went by, he became very big.”

Sonny and Wolchock parted ways when Wolchock quit the railway to work full-time at alcohol production, but other partners came on side. Every one of them was the same: blue collar men like Wolchock who made a living with their hands.

During Prohibition in the 1920s, Bill Wolchock ran the biggest bootlegging business in Manitoba. He was producing tens of thousands of gallons of 65% overproof alcohol – 94% pure alcohol.

Later, after his business took off, Wolchock shipped almost exclusively to the United States and mostly to gangsters. He stored illegal in farmers’ barns from the village of Reston in southwestern Manitoba to the village of Tolstoi in southeastern Manitoba. He stored illegal booze in a coal yard that used to be on Osborne Street in Winnipeg; in a large automobile service station in St. Boniface;. and in a St. Boniface lumberyard. He stored booze in a Pritchard Avenue horse barn. Those are just some of the known locations.

At the height of the Great Depression, Leonard estimates his father employed as many as 50 people who would not have been able to put food on the table otherwise. “They all had families, they all had houses, they all could put groceries on the table, thanks to the illegal business,” said Leonard.

Crooks or entrepreneurs?

Wolchock’s story has euded historians all these years. When Wolchock was finally caught and sentenced to five years in prison for income tax evasion, the Second World War was on, and his case didn’t get the publicity it might have otherwise. Besides, the Prohibition era had been over for more than a decade and was old news. Wolchock hadn’t gone straight like the whiskey-making Bronfman family, but had continued to bootleg long after Prohibition had ended.

Leonard Wolchock told the story of his father and a gang of North End bootleggers for the first time for this book. The story was checked against news clippings from the period.

Wolchock owned at least two large stills in Winnipeg. A huge four-story still operation in a building that was in the 1000 block on Logan Avenue, just east of McPhillips Street, that produced up to 400 gallons a day; and a huge still in a building that used to be on Tache Avenue, about 300 meters west of the Provencher Bridge on the river side. He also had smaller stills, often in rural locations and owned portable stills. He moved around from barn to barn outside Winnipeg to elude police.

Wolchock never considered what he was doing wrong, said his son. He thought the governments were wrong. People were going to find a way to drink one way or another.

“My father was a manufacturer. He was filling a niche market. I’m not ashamed of anything he did,” said Leonard.

Even the police chief who lived just five doors down from the Wolchock home at 409 Boyd Avenue would drop in regularly for a friendly drink. The fire commissioner, who lived one street over on College Avenue and three houses down, was another thirsty visitor. Granted, Wolchock ran a little import liquor businesses as a front, which was legal at the time, but Leonard has little doubt the authorities knew what his father’s main source of income was.

“The chief of police knew what my father was doing, and the fire chief was over at our place all the time!” said Leonard.

When the RCMP finally moved in on his father for income tax evasion, it was a measure of the respect for Wolchock that he was never arrested. Police called his dad with the news, said Leonard. “The police chief phoned up and said, ‘Bill, I want you to come down.’ They never sent anyone to get him.”

Booze, glorious booze! Was it more glamorous in Prohibition when it was illegal, or was the illegal liquor trade more harmful by turning otherwise law abiding men into criminals? Was illegal liquor more dangerous to your health (alcohol poisoning), and did concealed drink drinking lead to more serious drinking problems?

While both Canada and the United States brought in Prohibition, there was a great gulf in how Prohibition played out in the two countries. Like a typical Canadian TV drama, Prohibition was more shouting than shooting in Canada. In the United States, it was more shooting. Much more.

Corpses in the gangster booze wars in the US were rarely found with just one or two bullets in them, but four, five, eight. Gangsters adopted the submachine gun invented by John Thompson in the 1920s, variously dubbed the Tommy Gun, Chopper Gat, and Chicago Typewriter. Frank Gusenberg took 22 bullets in the famous St. Valentine’s Day Massacre in Chicago, when Al Capone’s men disguised as police officers lined up seven of George “Bugs” Moran’s men against a warehouse wall and opened fire. One creative reporter at the time wrote the machine guns “belched death.”

These two news stories from a single September day in 1930 on the front page of the Manitoba Free Press are typical:

Detroit, Michigan: “An unidentified man was killed tonight by two assassins, armed with sawed-off shotguns who stepped out of an automobile, fired four charges into the body of their victim and escaped in the auto. It was the third gang killing of the week here.

Elizabeth, New Jersey: “Twelve gunmen waited in ambush within Sunrise Brewery here today, disarming a raiding party of seven dry agents and shot and killed one of the invaders.” One federal agent was found shot eight times. “The gangsters, who apparently had been forewarned of the raid, than escaped.”

There are likely several reasons why Canada didn’t go the gangster route. One, there were more loopholes in Canadian law to get liquor if you wanted. For example, you could get a prescription for “medical” brandy. Two, we have never been as gun-happy as the Americans. And three, our Prohibition didn’t last as long. Prohibition in the U.S. ran from 1920-1933. In Manitoba, Prohibition started in 1916 and ended in 1923.

While Canada didn’t have the gang wars like down south, it did become the feeder system, the exporter, the good neighbour and free trader to the U.S. for liquor. Our Prohibition was winding down just as American Prohibition was getting started in 1920. How fortuitous for an enterprising bootlegger! Manitobans could legally buy liquor from the government and run it across the border into the hands of thirsty Americans.

And being neighbourly, we did. One of the major gateways was the Turtle Mountains in southwestern Manitoba. Booze poured through the hills, said James Ritchie, archivist with the Boissevain and Morton Regional Library.

“A longstanding tradition of smuggling through the Turtle Mountains already existed before Prohibition. People had already been smuggling things across for 50 years or more, so alcohol was just more item of trade,” Richie said.

Minot, North Dakota, of all places, was a gangster haven and was dubbed “Little Chicago” back then. A railway town, it served it as a distribution hub for liquor coming in from Manitoba and Saskatchewan.

The 65-kilometer border of Turtle Mountain Hills is carved with trails every few kilometers so there was no way a border patrol could close down the rum running, said Richie. Many of the trails were simply road allowances where a road hadn’t got built. “If you tried to cross anywhere near Emerson, where it’s so flat, the custom guard could see your car coming from 10 miles away. You can’t do that in the Turtles. The custom guard can’t see you from 500 feet away,” said Ritchie.

Many a poor southwestern Manitoba farm family augmented their income with a little rumrunning. They could buy a dozen bottles every two weeks, the government-set allotment for personal use, and sell it for profit just a few miles away. “Prohibition created an economic opportunity for a lot of families,” said Ritchie.

But it was small trade compared to what the Bronfmans would do. Ezekiel and Mindel Bronfman arrived in Brandon in the late 1800s. The 1901 Canada Census lists them as residents of Brandon, along with their children, including Harry and Sam. It was after the Bronfmans had moved to Saskatchewan that they began selling whiskey to the United States in the 1920s. They exported whiskey by the boxcar-load. They later moved to Brandon briefly, where they continued the rumrunning before finally setting up in Montreal.

Meanwhile, Winnipeg was the bacchanalia of the West prior to Prohibition, as the late popular history writer James H Gray, liked to say. By 1882, Winnipeg had 86 hotels, most of which had had saloons. It also had five breweries, 24 wine and liquor stores (15 of which were on Main Street), and 64 grocery stores selling whiskey. The population was just 16,000.

When government turned off the tap, Manitobans went underground. Private stills sprang up everywhere. Ukrainian farmers were famous for their stills and acted as engineering consultants for the rest of the community. The Ukrainians seemed to have an inborn talent for erecting the contraptions, and some stills made the old country potato whiskey. In Ukrainian settlements like Vida, Sundown, and Tolstoi someone’s child was always assigned the task of changing the pail from under the spigot that caught the slow dripping distilled whiskey.

Even Winnipeg Mayor Ralph Webb, who had an artificial leg and was manager of the Marlborough Hotel, campaigned for more liberal liquor laws. Webb wanted to attract tourism by promoting Winnipeg as “the city of snowballs and highballs.”

The United States was interested in the Canadian experiment with Prohibition and summoned Francis William Russell, president of the Moderation League of Manitoba, a group that opposed Prohibition, to a U.S. Senate committee in Washington in 1926. Russell said Prohibition simply resulted in the proliferation of stills in Manitoba.

Arrests for illegal stills rose from 40 in 1918, two years into Prohibition in Manitoba, to 300 by 1923. “We found that the province of Manitoba was covered with stills,” he said. He claimed Prohibition hadn’t stopped drinking, it had just kicked it out of the public bar and into the home where it wreaked havoc on families.

One of the strangest still stories took place in the RM of Springfield, just east of Winnipeg, when an RCMP officer and a Customs inspector came across a “mystery” shack. Sure enough, they found a still inside and went in and began dismantling the evidence. Unknown to them, the owners arrived, saw what was going on, and set fire to the shack with them in it. The agents escaped the flames in time, but so did the arsonists, and no charges were laid.

Yet historical accounts only mentioned small stills in Manitoba. Some historians concluded there was no major bootlegging out of Winnipeg, just small neighbourhood and homestead stills. The story of Bill Wolchock shows that not to be true.

Winnipeg had two large thirsty markets in its vicinity: the Twin Cities, St. Paul and Minneapolis in Minnesota, and to a lesser extent, Chicago, Illinois.

St. Paul was a nest of gangsters. John Dillinger, Baby Face Nelson, Machine Gun Kelly, and Ma Barker and her sons, all took refuge in the city at one time or another. The person who ran the underworld in St. Paul was gangster Isadore “Kid Cann” Blumenfeld.

Chicago, of course, was the gangster capital of North America, controlled by Al Capone.

Capone was just 25 years old when he controlled Chicago. It does seem that Prohibition brought many young people into crime. Another Chicago bootlegger, Hymie Weiss, was gunned down by Capone’s men at the tender age of 28. “Hymie Weiss was not Jewish as his name suggests, but Catholic. His real name was Wajciechowski, and Hymie was a nickname.)

Wolchock and his partners were in their early twenties when they started selling booze. Wolchock shipped pure alcohol to both the Twin Cities and Chicago, but more so to Minnesota. When his son Leonard attended a convention in Minneapolis years later, he was feted by a gangster-looking character who recognized Leonard’s resemblance to his father. The gangster offered to foot his bill.

Wolchock Sr. Also sold to Duluth, Minnesota, and to Alberta distilleries. It’s also likely he was also shipping to Minot, since he was storing alcohol in barns in southwestern Manitoba. His business was selling to other manufacturers who brewed the pure alcohol into liquor. He would get rich from it.

Archibald William Wolchock was born in Minsk, Russia, which is now in Ukraine, in 1898, and came to Winnipeg in 1906 with his parents. He grew up and married and lived at 409 Boyd Avenue, at the corner of Boyd and Salter Street. Wolchock wasn’t a gangster, but he sold to them. Leonard believes his father likely dealt with Kid Cann in the Twin Cities, who ran the illegal liquor business there. “My dad did a lot of business in St. Paul,” said Leonard.

Most of what Leonard knows about his dad’s business was told to him by friends and associates of his dad. His father followed the code of the day and kept his business and home separate. Wolchock had a simple rule for his son if people should ask about his work: he would press his index finger to his lips.

While at Assiniboia Downs a man once approached Leonard and said he knew his dad. This sort of thing happened a lot in Leonard’s life because he resembled his dad.

“The guy was a railroader,” Leonard related. “He said, ‘I knew your dad. We stole a train for him once. I said, ‘Get out of here.’ He said, ‘Listen, your dad said he had a big shipment going to Chicago that he couldn’t deliver by car. I told him, ‘Don’t worry, Bill.’ The man said a crew of four, including a brakeman, pulled an engine and three box cars over at Bergen cut-off and loaded them with alcohol. The alcohol, when it went by rail, was shipped in 45 gallon drums. Somewhere along the track, the railway men switched the cars over to the Soo Line track that went to Chicago. When the payoff came, Wolchock showed up at a secret location and dished out $100 bills like playing cards to the railroaders.

The Bronfman family knew about Wolchock and Wolchock, of course, knew about them. Wolchock was friendly with the Bronfman brother-in-law, Paul Matoff, who ran Bronfman stores in Carduff, Gainsborough, and Bienfait, Saskatchewan where he sold whiskey to American rumrunners. On October 4th, 1922, Matoff took payment from a North Dakota bootlegger. Shortly after a 12-gauge shotgun blast killed him instantly in the railway station. The murder was never solved.

“Matoff told my dad, ‘Bill, your market is in the States,’” said Leonard.

Another time a friend of Wolchock Sr., nicknamed Tubby, took Leonard aside. They bumped into each other at the hospital, where Wolchock was dying. “Tubby said he and his brother had a truck, and one day my dad called and asked if they had a tarp for the truck. They said, yeah, so dad said, “Go to such and such place, back up your truck, don’t get out, don’t look in the mirror, don’t do nothing. Someone will put something in your truck. Then go to this address and do the same. Don’t get out, don’t look in your rearview mirror, don’t do nothing.’ That’s how business was done.”

Wolchock was always a sharp dresser and wore suits and long overcoats. His shirts were specially made by Maurice Rothschild’s in Minneapolis and monogrammed AWW across the pocket. His suits were made in the Abe Palay tailor shop that used to be on Garry Street across from the old Garrick Theater. “My dad wore a fedora because he was bald,” said Leonard. One of Wolchock‘s favourite hangouts was the Russian Steam Baths on Dufferin Avenue, where he went Wednesdays and Saturdays.

When that closed, he and his bootleg pals went to Obee’s Steam Baths on McGregor near Pritchard.

Wolchock had a chain of people with various trades and skills on the payroll and always paid well. For example, he had agreements with several tinsmiths to make him the gallon cans to put the alcohol in when it was being smuggled by car.

One tinsmith told Leonard he used to make $200-$400 per week moonlighting for his father. He earned $30 a week on his day job as a tinsmith.

The gallon cans would be put in jute bags and tossed in the back of a car. The drivers would go across the border at small town points like Tolstoi and Gretna.

Border security back then wasn’t like it is today.

Wolchock couldn’t buy anything in bulk, like the sugar to make the alcohol or the cans to put the liquor into, because it would attract too much attention. So he had deals all over the place. He had a deal with a major local bakery, which used to have a central bakery and stores around Winnipeg, to supply him the sugar. He also had a deal with a bakery out on the West Coast.

Wolchock even had deals with hog farmers to get rid of the mash from alcohol production, which makes an excellent feedstuff for livestock. He had drivers and sales agents. He had a chemist on the payroll.

Wolchock also had two or three henchmen. They carried guns in shoulder holsters and hung around the family, but they were the only business associates that ever came to the house. “My dad lived a normal life. We sat and listened to hockey games, but he had strong-armed men around if there was any trouble,” Leonard recalled.

“My dad wasn’t a run-around,” said Leonard. “He was a family man. He was home for lunch and dinner all the time.”

Wolchock also had a friend highly placed with the federal excise office in Winnipeg. His name cannot be revealed here. He also had a highranking local bank official who helped him, but Leonard also doesn’t know in what way. Wolchock once gave his sister $30,000 to deposit in a bank, but that’s all Leonard knows about the transaction. Later in life, Leonard once asked the banker, a big gruff man who always smoked a cigar, what his arrangement was with his father. “None of your f-ing business,” the banker snapped.

One of the problems for Wolchock was where to put the money. He made piles of money, but he couldn’t deposit it in the bank like everyone else because he couldn’t explain to authorities how he made it. Leonard thinks he stashed it, but doesn’t know where. While the family didn’t live ostentatiously, perhaps because that would have attracted attention, they always had money at a time when most people didn’t. “People were dirt poor. There was no money around,” said Leonard. All four of Wolchock ‘s sons received vehicles when they were old enough to drive and all would later get houses when they left home.

One of Wolchock’s hobbies was collecting racehorses with names like Dark Wonder, Sun Trysts, Let’s Pretend. “My dad had a stable of horses in the early days to just get rid of the money,” said Leonard. Leonard’s mother Rose used to travel to watch the horses race at major racetracks in California and Hastings Park in Vancouver. Other enterprises Wolchock invested in included buying a ladies’ garment factory and the Sylvia Hotel in Vancouver. Leonard believes his father may have been a millionaire by the time he married Rose in 1927. Leonard was born the next year. “My mother’s family was poor. Dad gave them lots of money. He paid for everything. Money was of no consequence.”

His parents regularly took vacations in Hot Springs, Arkansas, which was sort of a racketeer tourist destination at the time, with legal gambling introduced thanks to gangster Meyer Lansky. It also had bath houses with natural hot springs. For some reason, racketeers had a thing for steam baths and hot springs.

Leonard claims – and insists it’s true – that his father would carry around $15,000 on him all the time. He once walked into a car dealership on Portage Avenue where McNaught Motors is now and bought a Cadillac on the spot with cash. “I never saw my dad with a wallet. All he had was a roll of bills with an elastic around it.”

Everything was in cash. For his bootlegging business Wolchock would buy six to eight cars at a time for his rumrunners to transport booze. He bought the cars at two Winnipeg dealerships where he had business relations. The first thing he always did with the new cars was tear out the backseat so he could fit in more alcohol. The stable of cars was parked inside a St. Boniface service garage. The runners had access day and night, mostly night. They sometimes went all the way to destinations like St. Paul, but usually they would just cross the border and unload into a shuttle car driven by an American rumrunner.

Wolchock and his merry men were a crosssection of Manitoba nationalities and religious origins in the 1920s. Wolchock was Jewish, and his cohorts were a mix of Poles, Frenchmen, Scotsmen, Ukrainians, Jews, Mennonite farmers near Steinbach, and Belgians – “a lot of Belgians,” Leonard said.

Leonard doesn’t know exactly how many people it took to run a still, maybe eight for the larger ones. When RCMP busted Wolchock‘s large still on Logan Avenue in 1936, it was the largest still ever found in Manitoba. Its operations extended to all four floors and into the basement, according to the Manitoba Free Press. The building also had an office, two vehicles and living quarters on the third floor. Employees gained entrance to the living quarters through a crawl space. In the living quarters were bunk beds and cooking equipment and books. The building was empty when police raided it. No charges were laid. The building was owned by the city from a tax sale.

Even after Prohibition ended and liquor was legal, it was government-controlled in Canada, so good money could still be made in bootlegging. The Bronfmans had managed the tricky business from illegal bootlegger to legal distiller, but not Wolchock. Like most law breakers, he didn’t quit while he was ahead.

RCMP finally charged Wolchock after customer Howard Gimble of Minneapolis got caught and ratted on him. Gimble was the key witness against Wolchock. The Manitoba Free Press reported that RCMP had tried been trying to nail Wolchock for years before Gimble gave them their break.

The charge was conspiring to defraud the federal government out of income tax moneys on liquor sales. The RCMP claimed he defrauded the government of $125,000, but that that was just a figure plucked out of the air, based on the scale of operation from a single portable still. The jury was locked up for the 10-day trial because of previous suspicions of jury tampering. Gimble told the court Wolchock had a portable still he moved from farm to farm near Winnipeg. RCMP found the still on Paul Demark’s farm in Prairie Grove, now a bedroom community at the end of Ste. Anne’s Road, just past the Winnipeg perimeter. But Gimble told the court Wolchock also used the still on the farm of Abraham Toews near Ste. Anne on Dave Letkeman’s farm just southeast of Steinbach, and in Jay Kehler’s barn one mile west of Steinbach. Court was also shown pictures of warehouses and buildings around Winnipeg, including St. Boniface, used in Wolchock ‘s illegal liquor business. Gimble also alleged Wolchock operated another still on a farm near Stonewall. He said it produced five thousands of gallons of alcohol that summer of 1940.

Wolchock and seven of his partners were convicted, but it took three trials. The first trial was declared a mistrial due to suspicion of jury tampering. In the second trial proceedings were halted when Wolchock required a hernia operation. Finally, he was sent to jail.

He got five years in Stony Mountain Penitentiary, and that was before there was such a thing as parole. It is the most severe sentence ever laid in Manitoba history for a liquor offense. Up to that point in March of 1940, no one had received more than an eight-month sentence for liquor offenses in Manitoba. Also convicted and sentenced were Ned Balakowski, three years; Ben Balakowski, eight months; Frank McGirl, eight months; Jules Mourant, one year. Sam Arborg, Eugene Mourant, and Cass Morant each received suspended sentences.

After serving his time, Wolchock remembered the people who helped him in prison. A prison guard at Stony Mountain named Mr. Anderson was always kind to Wolchock. When Wolchock finished his prison term, Leonard was sent out every Christmas over to the Anderson household to deliver food and presents.

Wolchock Sr. also gave generously to the Salvation Army. “He was a great guy to the Salvation Army because the Sally Ann was very good to him in jail,” said Leonard. His father also saw to it that Leonard took Jewish dishes to the Jewish prisoners in Stony Mountain on the high holidays.

He had money left when he got out of jail but the cost of lawyers for three trials drained a lot of it. Wolchock paid everybody’s legal fees. His wife Rose managed their family of four young boys while he was in prison for five years, and Wolchock, when he got out, bought the home then called Bardal Estate, formerly owned by Winnipeg Funeral Director Neil Bardal. It’s a large clapboard house at the end of Hawthorne Avenue in North Kildonan, along the river on what is now named Kildonan Drive. “There was a fireplace in every bedroom,” Leonard recalled. Wolchock also had money to buy a little company, Canadian Wreckage and Salvage.

But the money wasn’t anything like he was used to and, after a couple years, Wolchock called his old mates together for a meeting. He wanted to make one last batch. Who was in? So the men walled off a portion of the Bardal’s home basement. Two of Wolchock’s close friends were bricklayers – and they constructed a still behind the wall. There were no neighbors on Kildonan Drive at the time, so there was no one to detect the smell from alcohol production. The men made the alcohol, distributed to people they could trust, and dismantled the operation. Then they rode off into the sunset.

“The old man had a bundle of money and he dished out to everyone. Louis went to Sudbury and got a 7-Up franchise; Charlie went to California and bought a liquor store; Benny G bought a trucking company; Benny B moved to Vancouver; Ned went back to work.” There were others involved, but Leonard doesn’t know what became of them. Other partners had already taken their money and invested before the RCMP arrest: Johnny B moved to Vancouver and bought a furniture store; Fred S bought a retail fish store in Winnipeg that still exists today under different owners; another partner went into the hotel business.

And Wolchock? “My dad started Capital Lumber at 92 Higgins Avenue with a partner,” said Leonard. “He didn’t make money like in the past, but he still called the shots and had a successful little business.”

That was Prohibition.

“There was honour among men. Back then, your word was your bond. Nothing was written down. Everything was a handshake,” said Leonard.

“My dad came to this country and he always called it the land of milk and honey. He always said that. He said it after he got out of prison, too. He was never bitter.”

Archibald William Wolchock died in 1976 at age 78.

Features

ClarityCheck: Securing Communication for Authors and Digital Publishers

In the world of digital publishing, communication is the lifeblood of creation. Authors connect with editors, contributors, and collaborators via email and phone calls. Publishers manage submissions, coordinate with freelance teams, and negotiate contracts online.

However, the same digital channels that enable efficient publishing also carry risk. Unknown contacts, fraudulent inquiries, and impersonation attempts can disrupt projects, delay timelines, or compromise sensitive intellectual property.

This is where ClarityCheck becomes a vital tool for authors and digital publishers. By allowing users to verify phone numbers and email addresses, ClarityCheck enhances trust, supports safer collaboration, and minimizes operational risks.

Why Verification Matters in Digital Publishing

Digital publishing involves multiple types of external communication:

- Manuscript submissions

- Editing and proofreading coordination

- Author-publisher negotiations

- Marketing and promotional campaigns

- Collaboration with illustrators and designers

In these workflows, unverified contacts can lead to:

- Scams or fraudulent project offers

- Intellectual property theft

- Miscommunication causing delays

- Financial loss due to fraudulent payments

- Unauthorized sharing of sensitive drafts

Platforms like Reddit feature discussions from authors and freelancers about using verification tools to safeguard their work. This highlights the growing awareness of digital safety in creative industries.

What Is ClarityCheck?

ClarityCheck is an online service that enables users to search for publicly available information associated with phone numbers and email addresses. Its primary goal is to provide additional context about a contact before initiating or continuing communication.

Rather than relying purely on intuition, authors and publishers can access structured information to assess credibility. This proactive approach supports safer project management and protects intellectual property.

You can explore community feedback and discussions about the service here: ClarityCheck

Key Benefits for Authors and Digital Publishers

1. Protecting Manuscript Submissions

Authors often submit manuscripts to multiple editors or publishers. Before sharing full drafts:

- Verify the contact’s legitimacy

- Ensure the communication aligns with known publishing entities

- Reduce risk of unauthorized distribution

A quick lookup can prevent time-consuming disputes and protect original content.

2. Safeguarding Collaborative Projects

Digital publishing frequently involves external contributors such as:

- Illustrators

- Designers

- Editors

- Ghostwriters

Verification ensures all collaborators are trustworthy, minimizing the chance of intellectual property theft or miscommunication.

3. Enhancing Marketing and PR Outreach

Promoting a book or digital publication often involves connecting with:

- Bloggers

- Reviewers

- Book influencers

- Digital media outlets

Before sharing press kits or marketing materials, verifying email addresses or phone contacts adds confidence and prevents potential misuse.

How ClarityCheck Works

While the internal system is proprietary, the user workflow is straightforward and efficient:

| Step | Action | Outcome |

| 1 | Enter phone number or email | Search initiated |

| 2 | Aggregation of publicly available data | Digital footprint analyzed |

| 3 | Report generated | Structured overview presented |

| 4 | Review by user | Informed decision before engagement |

The platform’s simplicity makes it suitable for authors and publishing teams, even those with limited technical expertise.

Integrating ClarityCheck Into Publishing Workflows

Manuscript Submission Process

- Receive submission request

- Verify contact via ClarityCheck

- Confirm identity of editor or publisher

- Share draft or proceed with collaboration

Collaboration with Freelancers

- Initiate project with external contributors

- Run ClarityCheck to verify email or phone number

- Establish project agreement

- Begin content creation safely

Marketing Outreach

- Contact media or reviewers

- Verify digital identity

- Share promotional materials with confidence

Ethical and Privacy Considerations

While ClarityCheck provides useful context, it operates exclusively using publicly accessible information. Authors and publishers should always:

- Respect privacy and data protection regulations

- Use results responsibly

- Combine verification with personal judgment

- Avoid sharing sensitive data with unverified contacts

Responsible use ensures the platform supports security without compromising ethical standards.

Real-World Use Cases in Digital Publishing

Scenario 1: Verifying a New Editor

An author is contacted by an editor claiming to represent a small publishing house. Running a ClarityCheck report confirms the email domain aligns with publicly available information about the company, reducing risk before signing an agreement.

Scenario 2: Screening Freelance Illustrators

A digital publisher seeks an illustrator for a children’s book. Before sharing project details or compensation terms, ClarityCheck verifies contact information, ensuring the artist is legitimate.

Scenario 3: Marketing Outreach Safety

A self-publishing author plans a social media and email campaign. Verifying influencer or reviewer contacts helps prevent marketing materials from reaching fraudulent accounts.

Why Verification Strengthens Publishing Operations

In digital publishing, speed and creativity are essential, but they must be balanced with security:

- Protect intellectual property

- Maintain trust with collaborators

- Ensure financial transactions are secure

- Prevent delays due to miscommunication

Verification tools like ClarityCheck integrate seamlessly, allowing authors and publishing teams to focus on creation rather than risk management.

Final Thoughts

In a world where publishing is increasingly digital and collaborative, verifying contacts is not just prudent — it’s necessary.

ClarityCheck empowers authors, editors, and digital publishing professionals to confidently assess phone numbers and email addresses, protect their intellectual property, and streamline communication.

Whether managing manuscript submissions, coordinating external contributors, or launching marketing campaigns, integrating ClarityCheck into your workflow ensures clarity, safety, and professionalism.

In digital publishing, trust is as important as creativity — and ClarityCheck helps safeguard both.

Features

Israel’s Arab Population Finds Itself in Dire Straits

By HENRY SREBRNIK There has been an epidemic of criminal violence and state neglect in the Arab community of Israel. At least 56 Arab citizens have died since the beginning of this year. Many blame the government for neglecting its Arab population and the police for failing to curb the violence. Arabs make up about a fifth of Israel’s population of 10 million people. But criminal killings within the community have accounted for the vast majority of Israeli homicides in recent years.

Last year, in fact, stands as the deadliest on record for Israel’s Arab community. According to a year-end report by the Center for the Advancement of Security in Arab Society (Ayalef), 252 Arab citizens were murdered in 2025, an increase of roughly 10 percent over the 230 victims recorded in 2024. The report, “Another Year of Eroding Governance and Escalating Crime and Violence in Arab Society: Trends and Data for 2025,” published in December, noted that the toll on women is particularly severe, with 23 Arab women killed, the highest number recorded to date.

Violence has expanded beyond internal criminal disputes, increasingly affecting public spaces and targeting authorities, relatives of assassination targets, and uninvolved bystanders. In mixed Arab-Jewish cities such as Acre, Jaffa, Lod, and Ramla, violence has acquired a political dimension, further eroding the fragile social fabric Israel has worked to sustain.

In the Negev, crime families operate large-scale weapons-smuggling networks, using inexpensive drones to move increasingly advanced arms, including rifles, medium machine guns, and even grenades, from across the borders in Egypt and Jordan. These weapons fuel not only local criminal feuds but also end up with terrorists in the West Bank and even Jerusalem.

Getting weapons across the border used to be dangerous and complex but is now relatively easy. Drones originally used to smuggle drugs over the borders with Egypt and Jordan have evolved into a cheap and effective tool for trafficking weapons in large quantities. The region has been turning into a major infiltration route and has intensified over the past two years, as security attention shifted toward Gaza and the West Bank.

The Negev is not merely a local challenge; it serves as a gateway for crime and terrorism across Israel, including in cities. The weapons flow into mixed Jewish-Arab cities and from there penetrate the West Bank, fueling both organized crime and terrorist activity and blurring the line between them.

The smuggling of weapons into Israel is no longer a marginal criminal phenomenon but an ongoing strategic threat that traces a clear trail: from porous borders with Egypt and Jordan, through drones and increasingly sophisticated smuggling methods, into the heart of criminal networks inside Israel, and in a growing number of cases into lethal terrorist operations. A deal that begins as a profit-driven criminal transaction often ends in a terrorist attack. Israeli police warn that a population flooded with illegal weapons will act unlawfully, the only question being against whom.

The scale of the threat is vast. According to law enforcement estimates, up to 160,000 weapons are smuggled into Israel each year, about 14,000 a month. Some sources estimate that about 100,000 illegal weapons are circulating in the Negev alone.

Israeli cities are feeling this. Acre, with a population of about 50,000, more than 15,000 of them Arab, has seen a rise in violent incidents, including gunfire directed at schools, car bombings, and nationalist attacks. In August 2025, a 16-year-old boy was shot on his way to school, triggering violent protests against the police.

Home to roughly 35,000 Arab residents and 20,000 Jewish residents, Jaffa has seen rising tensions and repeated incidents of violence between Arabs and Jews. In the most recent case, on January 1, 2026, Rabbi Netanel Abitan was attacked while walking along a street, and beaten.

In Lod, a city of roughly 75,000 residents, about half of them Arab, twelve murders were recorded in 2025, a historic high. The city has become a focal point for feuds between crime families. In June 2025, a multi-victim shooting on a central street left two young men dead and five others wounded, including a 12-year-old passerby. Yet the killing of the head of a crime family in 2024 remains unsolved to this day; witnesses present at the scene refused to testify.

The violence also spilled over to Jewish residents: Jewish bystanders were struck by gunfire, state officials were targeted, and cars were bombed near synagogues. Hundreds of Jewish families have left the city amid what the mayor has described as an “atmosphere of war.”

Phenomena that were once largely confined to the Arab sector and Arab towns are spilling into mixed cities and even into predominantly Jewish cities. When violence in mixed cities threatens to undermine overall stability, it becomes a national problem. In Lod and Jaffa, extortion of Jewish-owned businesses by Arab crime families has increased by 25 per cent, according to police data.

Ramla recorded 15 murders in 2025, underscoring the persistence of lethal violence in the city. Many victims have been caught up in cycles of revenge between clans, often beginning with disputes over “honour” and ending in gunfire. Arab residents describe the city as “cursed,” while Jewish residents speak openly about being afraid to leave their homes

Reluctance to report crimes to the authorities is a central factor exacerbating the problem. Fear of retaliation by families or criminal organizations deters victims and their relatives from coming forward, contributing to a clearance rate of less than 15 per cent of all murders. The Ayalef report notes that approximately 70 per cent of witnesses refused to cooperate with police investigations, citing doubts about the state’s ability to provide protection.

Violence in Arab society is not just an Arab sector problem; it poses a direct and serious threat to Israel’s national security. The impact is twofold: on the one hand, a rise in crime that affects the entire population; on the other, the spillover of weapons and criminal activity into terrorism, threatening both internal and regional stability. This phenomenon reached a peak in 2025, with implications that could lead to a third intifada triggered by either a nationalist or criminal incident.

The report suggests that along the Egyptian and Jordanian borders, Israel should adopt a technological and security-focused response: reinforcing border fences with sensors and cameras, conducting aerial patrols to counter drones, and expanding enforcement activity.

This should be accompanied by a reassessment of the rules of engagement along the border area, enabling effective interdiction of smuggling and legal protocols that allow for the arrest and imprisonment of offenders. The report concludes by emphasizing that rising violence in cities, compounded by weapons smuggling in the Negev, is eroding Israel’s internal stability.

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.

Features

The Chapel on the CWRU Campus: A Memoir

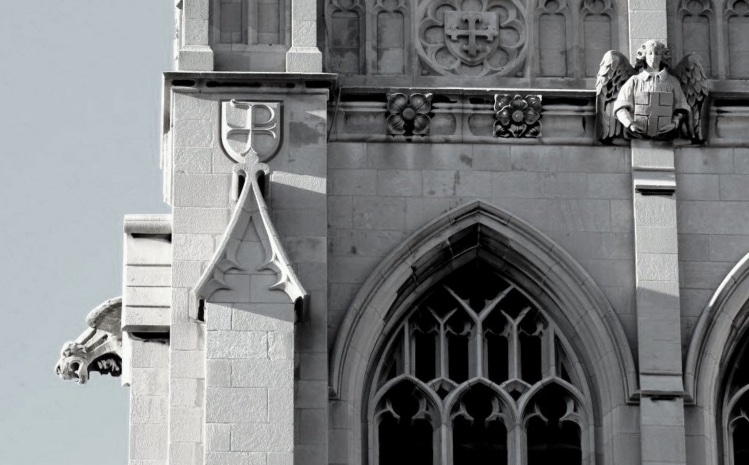

By DAVID TOPPER In 1964, I moved to Cleveland, Ohio to attend graduate school at Case Institute of Technology. About a year later, I met a girl with whom I fell in love; she was attending Western Reserve University. At that time, they were two entirely separate schools. Nonetheless, they share a common north-south border.

Since Reserve was originally a Christian college, on that border between the two schools there is a Chapel on the Reserve (east) side, with a four-sided Tower. On the top of the Tower are three angels (north, east, & south) and a gargoyle (west); the latter therefore faces the Case side. Its mouth is a waterspout – and so, when it rains, the gargoyle spits on the Case side. The reason for this, I was told, is that the founder of Case, Leonard Case Jr., was an atheist.

In 1968, that girl, Sylvia, and I got married. In the same year the two schools united, forming what is today still Case Western Reserve University (CWRU). I assume the temporal proximity of these two events entails no causality. Nevertheless, I like the symbolism, since we also remain married (although Sylvia died almost 6 years ago).

Speaking of symbolism: it turns out that the story told to me is a myth. Actually, Mr. Case was a respected member of the Presbyterian Church. Moreover, the format of the Tower is borrowed from some churches in the United Kingdom – using the gargoyle facing west, toward the setting sun, to symbolize darkness, sin, or evil. It just so happens that Case Tech is there – a fluke. Just a fluke.

We left Cleveland in 1970, with our university degrees. Harking back to those days, only once during my six years in Cleveland, was I in that Chapel. It was the last day before we left the city – moving to Winnipeg, Canada – where I still live. However, it was not for a religious ceremony – no, not at all. Sylvia and I were in the Chapel to attend a poetry reading by the famed Beat poet, Allen Ginsberg.

My final memory of that Chapel is this. After the event, as we were walking out, I turned to Sylvia and said: “I’m quite sure that this is the first and only time in the entire long history of this solemn Chapel that those four walls heard the word ‘fuck’.” Smiling, she turned to me and said, “Amen.”

This story was first published in “Down in the Dirt Magazine,”

vol, 240, Mars and Cotton Candy Clouds.