Features

A replica jersey from a 1930s Jewish boys club in Winnipeg evokes fond memories for one of the members of that club

By BERNIE BELLAN In September 2020 I wrote a story about a long-ago Jewish club that went by the name “The Rollickers”. That story was prompted by my reading the minute book of the club, which had been in the hands of Rona Perlov, whose father, Eli Weinberg, was a founding member of the club. (By the way you can read that story on this website. Simply enter the name “The Rollickers” in our search engine.)

While reading that minute book certainly evinced a few laughs – those young guys spent more time debating about who should be punished for violating arcane rules about what constituted unacceptable behavior than anything else, I noted in my story that there was never any reference in the minutes to sports.

I wondered about that. While the YMHA on Albert Street didn’t open until 1936, there have been many stories written about great Jewish athletes from Winnipeg in the early part of the 20th century. Were they organized, I wondered? Did they have clubs?

My questions were partly answered a few weeks ago when I received a call from someone by the name of Murray Atnikov. It turned out that Atnikov was a former Winnipegger, now living in Vancouver, who had a story he wanted to share with me, but which he wanted to tell me in person. He would be coming to Winnipeg in August, he told me, and asked whether we could meet when he got here.

“Sure,” I told him. I was intrigued to find out what his story was.

Subsequently, Atnikov (who I learned, after talking to him on the phone when he called me again) is better known as Dr. Murray Atnikov, an anaesthesiologist who had left Winnipeg many years ago, came over to my house one beautiful summer day, complete with a folder which he didn’t open until we were well into our conversation.

When he was a teen in the 1930s, Atnikov told me, he belonged to a north end Jewish sports club known as “The Demons”. There was only one other surviving member of that club: Nathan Isaacs (née Isaacovitch), now a resident of Toronto (and a longtime subscriber to this paper, I might add.)

There was at least one other Jewish sports club of that era, Atnikov recalled, known as “The Eagles”. Members of both clubs played hockey, softball, and football, and their competition came from non-Jewish clubs in the area. When I asked Atnikov whether any of the boys curled, he said that was something older men did, but interestingly he told me that there was actually a football field located behind what was the Maple Leaf Curling Club on Machray, which was where the Demons and the Eagles played their games.

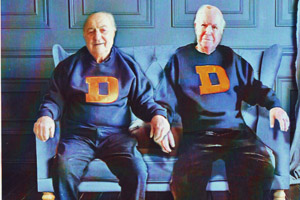

But why did Atnikov want to see me in person, I wondered? It turns out that in his folder he had some photographs, including one of him and Nathan Isaacs when they both served in the Royal Canadian Air Force, but also one of the two of them wearing replica sweaters emblazoned with the letter “D” for Demons.

As Atnikov explained to me, a son of one of their late colleagues had been going through his father’s belongings after his father had passed away when he came across an original “Demons” sweater from the 1930s.

Knowing that Atnikov and Isaacs were the two surviving members of the Demons, this fellow had the replica sweaters made up and shipped to Atnikov and Isaacs. Recently the two old friends had a chance to visit with one another – thus the photo you at the beginning of this story.

So, where did Murray Atnikov end up after the war, I wondered? As he sat with me on my front step, regaling me with one fascinating story after another, he explained how he ended up in Vancouver.

In 1945 Atnikov was one of a group of three friends who had applied to enter medical school here in Winnipeg. Although the quota on Jewish students had just been lifted, thanks to a legal battle entered into by such individuals as Percy Barsky and Hyman Sokolov (which has been well documented both in this paper and numerous other sources), it was still no easy matter for Jewish students to get into medicine here.

As a result, Atnikov said, he and his two friends boarded a train for Chicago, where they intended to apply to the University of Chicago’s medical school. While all three were accepted, Atnikov explained, they were told that there were two different streams within the medical school. In one stream, once you graduated, you would be allowed to practice medicine anywhere in the U.S. Within the other stream, however, you would be allowed to practice medicine only in Illinois. (For how long you’d have to remain in Illinois I’m not sure. I also didn’t ask Atnikov whether he knew the answer.)

Not wanting to be forced to remain in Illinois, however, Atnikov said he decided to return to Winnipeg and see whether there was any chance he might still be able to get into medical school here. Upon returning home and contacting the medical school yet again though, he was disappointed to learn that his name was still not on the list of entrants to the new year of school.

Although disappointed, you can imagine Atnikov’s elation when he received a follow-up call from the same person who told him his name was not on the list of medical school entrants to say that a mistake had been made. Apparently when the three young men had gone to Chicago and had all been accepted into medical school there, one of the other two guys phoned the medical school here to say that they could remove their names from the list of applicants to school in Winnipeg because they had all been accepted in Chicago.

It turns out that, while Atnikov was not immediately accepted into medical school, he was number two on the wait list and, pending two other students dropping out of school, he would get in – which he did.

Upon graduating from medicine in 1950, however, Atnikov left Winnipeg to advance his medical education at the University of Minnesota. One of his colleagues there was Norman Shumway, he told me, who later became an early pioneer of heart transplant surgery. (According to Atnikov, Christian Barnaard, who performed the first-ever heart transplant on a human, learned his technique from Shumway when they were both colleagues at the University of Minnesota in the 1950s.)

Atnikov went on to have an illustrious career as an anesthesiologist, in New York, California, and ultimately, Vancouver, which is where he eventually retired from practicing.

Still, after all these years, with all that he has accomplished, Murray Atnikov was most interested in talking about the Demons and what great times they had together.

Those boyhood memories – and girlhood ones too: They never cease to fade and reliving some of those experiences is what keeps so many of us going.

Features

BlackRock applies for ETF plan; XRP price could rise by 200%, potentially becoming the best-yielding investment in 2026.

Recently, global asset management giant BlackRock officially submitted its application for an XRP ETF, a piece of news that quickly sparked heated discussions in the cryptocurrency market. Analysts predict that if approval goes smoothly, the price of XRP could rise by as much as 200% in the short term, becoming a potentially top-yielding investment in 2026.

ETF applications may trigger a large influx of funds.

As one of the world’s largest asset managers, BlackRock’s XRP ETF is expected to attract significant attention from institutional and qualified investors. After the ETF’s listing, traditional funding channels will find it easier to access the XRP market, providing substantial liquidity support.

Historical data shows that similar cryptocurrency ETF listings are often accompanied by significant short-term market rallies. Following BlackRock’s application announcement, XRP prices have shown signs of recovery, and investor confidence has clearly strengthened.

CryptoEasily helps XRP holders achieve steady returns.

With its price potential widely viewed favorably, CryptoEasily’s cloud mining and digital asset management platform offers XRP holders a stable passive income opportunity. Users do not need complicated technical operations; they can receive daily earnings updates and achieve steady asset appreciation through the platform’s intelligent computing power scheduling system.

The platform stated that its revenue model, while ensuring compliance and security, takes into account market volatility and long-term sustainability, allowing investors to enjoy the benefits of market growth while also obtaining a stable cash flow.

CryptoEasily is a regulated cloud mining platform.

As the crypto industry rapidly develops, security and compliance have become core concerns for investors. CryptoEasily emphasizes that the platform adheres to compliance, security, and transparency principles and undergoes regular financial and security audits by third-party institutions. Its security infrastructure includes platform operations that comply with the European MiCA and MiFID II regulatory frameworks, annual financial and security audits conducted by PwC, and digital asset custody insurance provided by Lloyd’s of London.

At the technical level, the platform employs multiple security mechanisms, including bank-grade firewalls, cloud security authentication, multi-signature cold wallets, and an asset isolation system. This rigorous compliance system provides excellent security for users worldwide.

Its core advantages include:

● Zero-barrier entry: No need to buy mining machines or build a mining farm, even beginners can easily get started.

●Automated mining: The system runs 24/7, and profits are automatically settled daily.

● Flexible asset management: Earnings can be withdrawn or reinvested at any time, supporting multiple mainstream cryptocurrencies.

●Low correlation with price fluctuations: Even during short-term market downturns, cash flow remains stable.

CryptoEasily CEO Oliver Bruno Benquet stated:

“We always adhere to the principle of compliance first, especially in markets with mature regulatory systems, to provide users with a safer, more transparent and sustainable way to participate in digital assets.”

How to join CryptoEasily

Step 1: Register an account

Visit the official website: https://cryptoeasily.com

Enter your email address and password to create an account and receive a $15 bonus upon registration. You’ll also receive a $0.60 bonus for daily logins.

Step 2: Deposit crypto assets

Go to the platform’s deposit page and deposit mainstream crypto assets, including: BTC, USDT, ETH, LTC, USDC, XRP, and BCH.

Step 3: Select and purchase a mining contract that suits your needs.

CryptoEasily offers a variety of contracts to meet the needs of different budgets and goals. Whether you are looking for short-term gains or long-term returns, CryptoEasily has the right option for you.

Common contract examples:

Entry contract: $100 — 2-day cycle — Total profit approximately $108

Stable contract: $1000 — 10-day cycle — Total profit approximately $1145

Professional Contract: $6,000 — 20-day cycle — Total profit approximately $7,920

Premium Contract: $25,000 — 30-day cycle — Total profit approximately $37,900

For contract details, please visit the official website.

After purchasing the contract and it takes effect, the system will automatically calculate your earnings every 24 hours, allowing you to easily obtain stable passive income.

Invite your friends and enjoy double the benefits

Invite new users to join and purchase a contract to earn a lifetime 5% commission reward. All referral relationships are permanent, commissions are credited instantly, and you can easily build a “digital wealth network”.

Summarize

BlackRock’s application for an XRP ETF has injected strong positive momentum into the crypto market, with XRP prices poised for a significant surge and becoming a potential high-yield investment in 2026. Meanwhile, through the CryptoEasily platform, investors can steadily generate passive income in volatile markets, achieving double asset growth. This provides an innovative and sustainable investment path for long-term investors.

If you’re looking to earn daily automatic income, independent of market fluctuations, and build a stable, long-term passive income, then joining CryptoEasily now is an excellent opportunity.

Official website: https://cryptoeasily.com

App download: https://cryptoeasily.com/xml/index.html#/app

Customer service email: info@CryptoEasily.com

Features

Digital entertainment options continue expanding for the local community

For decades, the rhythm of life in Winnipeg has been dictated by the seasons. When the deep freeze sets in and the sidewalks become treacherous with ice, the natural tendency for many residents—especially the older generation—has been to retreat indoors. In the past, this seasonal hibernation often came at the cost of social connection, limiting interactions to telephone calls or the occasional brave venture out for essential errands.

However, the landscape of leisure and community engagement has undergone a radical transformation in recent years, driven by the rapid adoption of digital tools.

Virtual gatherings replace traditional community center meetups

The transition from physical meeting spaces to digital platforms has been one of the most significant changes in local community life. Where weekly schedules once revolved around driving to a community center for coffee and conversation, many seniors now log in from the comfort of their favorite armchairs.

This shift has democratized access to socialization, particularly for those with mobility issues or those who no longer drive. Programs that were once limited by the physical capacity of a room or the ability of attendees to travel are now accessible to anyone with an internet connection.

Established organizations have pivoted to meet this digital demand with impressive results. The Jewish Federation’s digital outreach has seen substantial engagement, with their “Federation Flash” e-publications exceeding industry standards for open rates. This indicates a community that is hungry for information and connection, regardless of the medium.

Online gaming provides accessible leisure for homebound adults

While communication and culture are vital, the need for pure recreation and mental stimulation cannot be overlooked. Long winter evenings require accessible forms of entertainment that keep the mind active and engaged.

For many older adults, the digital realm has replaced the physical card table or the printed crossword puzzle. Tablets and computers now host a vast array of brain-training apps, digital jigsaw puzzles, and strategy games that offer both solitary and social play options.

The variety of available digital diversions is vast, catering to every level of technical proficiency and interest. Some residents prefer the quiet concentration of Sudoku apps or word searches that help maintain cognitive sharpness. Others gravitate towards more dynamic experiences. For those seeking a bit of thrill from the comfort of home, exploring regulated entertainment options like Canadian real money slots has become another facet of the digital leisure mix. These platforms offer a modern twist on traditional pastimes, accessible without the need to travel to a physical venue.

However, the primary driver for most digital gaming adoption remains cognitive health and stress relief. Strategy games that require planning and memory are particularly popular, often recommended as a way to keep neural pathways active.

Streaming services bring Israeli culture to Winnipeg living rooms

Beyond simple socialization and entertainment, technology has opened new avenues for cultural enrichment and education. For many in the community, staying connected to Jewish heritage and Israeli culture is a priority, yet travel is not always feasible.

Streaming technology has bridged this gap, bringing the sights and sounds of Israel directly into Winnipeg homes. Through virtual tours, livestreamed lectures, and interactive cultural programs, residents can experience a sense of global connection that was previously difficult to maintain without hopping on a plane.

Local programming has adapted to facilitate this cultural exchange. Events that might have previously been attended by a handful of people in a lecture hall are now broadcast to hundreds. For instance, the community has seen successful implementation of educational sessions like the “Lunch and Learn” programs, which cover vital topics such as accessibility standards for Jewish organizations.

By leveraging video conferencing, organizers can bring in expert speakers from around the world—including Israeli emissaries—to engage with local seniors at centers like Gwen Secter, creating a rich tapestry of global dialogue.

Balancing digital engagement with face-to-face connection

As the community embraces these digital tools, the conversation is shifting toward finding the right balance between screen time and face time. The demographics of the community make this balance critical. Recent data highlights that 23.6% of Jewish Winnipeggers are over the age of 65, a statistic that underscores the importance of accessible technology. For this significant portion of the population, digital tools are not just toys but essential lifelines that mitigate the risks of loneliness associated with aging in place.

Looking ahead, the goal for local organizations is to integrate these digital successes into a cohesive strategy. The ideal scenario involves using technology to facilitate eventual in-person connections—using an app to organize a meetup, or a Zoom call to plan a community dinner.

As Winnipeg moves forward, the lessons learned during the winters of isolation will likely result in a more inclusive, connected, and technologically savvy community that values every interaction, whether it happens across a table or across a screen.

Features

Susan Silverman: diversification personified

By GERRY POSNER I recently had the good fortune to meet, by accident, a woman I knew from my past, that is my ancient past. Her name is Susan Silverman. Reconnecting with her was a real treat. The treat became even better when I was able to learn about her life story.

From the south end of Winnipeg beginning on Ash Street and later to 616 Waverley Street – I can still picture the house in my mind – and then onward and upwards, Susan has had quite a life. The middle daughter (sisters Adrienne and Jo-Anne) of Bernie Silverman and Celia (Goldstein), Susan was a student at River Heights, Montrose and then Kelvin High School. She had the good fortune to be exposed to music early in her life as her father was (aside from being a well known businessman) – an accomplished jazz pianist. He often hosted jam sessions with talented Black musicians. As well, Susan could relate to the visual arts as her mother became a sculptor and later, a painter.

When Susan was seven, she (and a class of 20 others), did three grades in two years. The result was that that she entered the University of Manitoba at the tender age of 16 – something that could not happen today. What she gained the most, as she looks back on those years, were the connections she made and friendships formed, many of which survive and thrive to this day. She was a part of the era of fraternity formals, guys in tuxedos and gals in fancy “ cocktail dresses,” adorned with bouffant hair-dos and wrist corsages.

Upon graduation, Susan’s wanderlust took her to London, England. That move ignited in her a love of travel – which remains to this day. But that first foray into international travel lasted a short time and soon she was back in Winnipeg working for the Children’s Aid Society. That job allowed her to save some money and soon she was off to Montreal. It was there, along with her roommate, the former Diane Unrode, that she enjoyed a busy social life and a place for her to take up skiing. She had the good fortune of landing a significant job as an executive with an international chemical company that allowed her to travel the world as in Japan, Hong Kong, New Zealand, Australia, Mexico, the Netherlands and even the USA. Not a bad gig.

In 1983, her company relocated to Toronto. She ended up working for companies in the forest products industry as well the construction technology industry. After a long stint in the corporate world, Susan began her own company called “The Resourceful Group,” providing human resource and management consulting services to smaller enterprises. Along the way, she served on a variety of boards of directors for both profit and non-profit sectors.

Even with all that, Susan was really just beginning. Upon her retirement in 2006, she began a life of volunteering. That role included many areas, from mentoring new Canadians in English conversation through JIAS (Jewish Immigrant Aid Services) to visiting patients at a Toronto rehabilitation hospital, to conducting minyan and shiva services. Few people volunteer in such diverse ways. She is even a frequent contributor to the National Post Letters section, usually with respect to the defence of Israel

and Jewish causes.

The stars aligned on New Year’s Eve, 1986, when she met her soon to be husband, Murray Leiter, an ex- Montrealer. Now married for 36 plus years, they have been blessed with a love of travel and adventure. In the early 1990s they moved to Oakville and joined the Temple Shaarei Beth -El Congregation. They soon were involved in synagogue life, making life long friends there. Susan and Murray joined the choir, then Susan took the next step and became a Bat Mitzvah. Too bad there is no recording of that moment. Later, when they returned to Toronto, they joined Temple Emanu-el and soon sang in that choir as well.

What has inspired both Susan and Murray to this day is the concept of Tikkun Olam. Serving as faith visitors at North York General Hospital and St. John’s Rehab respectively is just one of the many volunteer activities that has enriched both of their lives and indeed the lives of the people they have assisted and continue to assist.

Another integral aspect of Susan’s life has been her annual returns to Winnipeg. She makes certain to visit her parents, grandparents, and other family members at the Shaarey Zedek Cemetery. She also gets to spend time with her cousins, Hilllaine and Richard Kroft and friends, Michie end Billy Silverberg, Roz and Mickey Rosenberg, as well as her former brother-in-law Hy Dashevsky and his wife Esther. She says about her time with her friends: “how lucky we are to experience the extraordinary Winnipeg hospitality.”

Her Winnipeg time always includes requisite stops at the Pancake House, Tre Visi Cafe and Assiniboine Park. Even 60 plus years away from the “‘peg,” Susan feels privileged to have grown up in such a vibrant Jewish community. The city will always have a special place in her heart. Moreover, she seems to have made a Winnipegger out of her husband. That would be a new definition of Grow Winnipeg.