Features

The River – an excerpt from a new novel by former Winnipegger Zev Coehn

Introduction: The following story is an excerpt from a longer story in Zev Cohen’s new novel titled “Are You Still Alive?”

Introduction: The following story is an excerpt from a longer story in Zev Cohen’s new novel titled “Are You Still Alive?”

As Zev wrote to us recently, “this is Chapter One of my novel, “Are You Still Alive?” It is partially based on events recounted to me by my late father Moshe. The story, beyond being one of the countless tales of Jewish survival against all odds during the Holocaust, is also an allegory for the indomitable human spirit intertwined with Rabbi Akiva’s maxim ‘V’havta l’raecha kamocha’. I hope to have the complete novel published soon.

Zev’s writing has appeared several times in the past in this paper. His collection of short stories, titled “Twilight in Saigon,” was published in 2021.

Born in Israel, Zev lived in Winnipeg until he was 17, when he returned to Israel with his parents. He now spends half the year in Israel and half the year in Calgary, where his two sons live.

Chumak leads the way towards the river in the dark. I had walked the route from his hut to the riverbank in daylight a few times and am confident I know the path down to the water and back. This time, though, I intend to cross to the other side under cover of darkness. Chumak, who came up with the idea, eagerly insists on guiding me so, he says, I don’t get lost. He claims he can find his way blindfolded. I think he believes that if this works, he might soon be rid of us, although he hasn’t said anything openly about it. To be fair, my suspicion just might be a projection of my own pressing desire to escape on to Chumak, whom I trust implicitly.

This summer has been uncommonly wet, and tonight the clouds are scudding low, hiding the moon and stars and making it difficult for others to spot us. At first, the only sounds are those of our movement through the brush and the occasional whoosh of passing nightbirds. The path is not overly challenging, and my labored breathing and rapidly beating heart stem more from fear than physical effort. Though I’m soaked to the skin by the constant drizzle, it is a minor irritation in the face of what I expect lies ahead. The sudden rattle of machine-gun fire causes us to instinctively fall flat on the ground, but luckily it isn’t close by, and we move forward a moment later. Distant flickers of lightning and muffled thunder are the backdrops as I blunder through the undergrowth and futilely attempt to avoid trees. Banging my knee against a tree trunk while trying to keep up with Chumak, I stifle a cry of pain, and then suddenly, I slip and slide down the muddy embankment, unable to get any traction. He grabs me before I plunge headfirst into the river.

“Quiet, you’ll get us caught,” he whispers as he holds my arm in his vicelike grip. “There are German and Romanian patrols on both sides of the river. Be more careful, or you will end up dead before you begin.”

The slope ends at the lapping water’s edge, but the river is barely visible in the blackness. A dog begins to bark incessantly on the other side. Has it picked up our scent even before I start to swim? I have no choice but to take my chances. Along the opposite bank downriver, dim points of light seem to be moving—smugglers perhaps or night fishermen. It’s hard to estimate how far away they are. I hope the current doesn’t drag me to them, but there is no going back. At least, for now, no searchlights are combing this particular area. Chumak seems to have picked the right spot.

Lightning flashes again, stronger this time, and in that instant, I realize how far it is to the other side across the rippling current. My swimming experience is limited to a small, calm pond near home, where my brother taught me some strokes. The wide, flowing river looks ominous, but I’ve made it this far, and I can’t give up now. And Chumak urges me on. I’m already knee-deep in the water, shivering, but not because the water is especially frigid.

“You can do it,” he encourages me. “The current isn’t so strong at this time of year. You must do it. It’s your only hope. Go!”

I stop for a moment and turn to him. “If anything happens…if I don’t make it back, help Ella and Sophie, please. They have no one else.” I don’t want to sound as if I’m pleading, but I am.

“Go, nothing will happen. You’re going to save them and yourself,” he says. “It’s the only way. I will wait here till you reach the other side and when you get there, clap some stones together three times to let me know you are safely there. The sound carries far at night. I’ll hear it, and I’ll tell Pani Ella that you made it.” Amid everything, I notice that this is the first time he calls Ella by her name.

I move slowly into the deeper water. At first, it’s easy; the water is up to my chest, but my feet still touch the soft muddy bottom. Then, without warning, it drops away, and I’m flailing and swallowing water. Finally, I calm down, gain control, and begin to swim. The current takes hold and starts pushing me downriver. Sputtering, I force myself to fight the rising panic and use my arms and kick with my legs in a crawl that will hopefully propel me towards the unseen shoreline. It’s working, and I’m not drowning, but I’m weakening rapidly. The combination of sickness I haven’t completely recovered from since the camp and general malnutrition has sapped me of strength. My clothes are waterlogged and drag me down. This can’t continue much longer. How idiotic would it be, I think, if I drowned now before beginning my mission? Rolling over on my back, I take the pig’s bladder that Chumak wrapped the note in from my pocket, and holding it tight, I squirm out of my pants to lighten the load. I let the current carry me and turn on my back to stroke and move gradually in the riverbank direction. It is less exhausting this way.

I’ve lost any notion of time as I float on my back and see nothing but the overcast sky. Has it been minutes? An hour? I fear trying to stand. If it’s still deep, I might sink and not be able to come back up. At least the rain has stopped. Some clouds have dispersed, and I can see stars in the black sky. Then I hear it. A baying sound getting closer. Maybe a dog? Then barking. Yes, a dog. Thankfully I must be near the shore. My feet hit bottom. I totter through the shallow water and, in the faint moonlight, survey a pebbly beach fronting the tree line. There is no sign of the huts nor of the large two-story house Chumak had pointed out some days earlier opposite my point of departure.

The house, he told me, belonged to a certain Nicolescu, a wealthy Romanian and well-known smuggler before the war. Chumak suggested that my woman, as he called Ella, write a letter to Nicolescu in Romanian asking for his help crossing the river. I imagined that he would get the letter to the Romanian or at least knew someone who could do it, so it took me by surprise when he said, “You will bring the letter to him, and he will make the arrangements.”

It seemed like a far-fetched idea. Beyond the problem of my crossing the river, in itself seemingly suicidal, why, I asked, would any Romanian, not to mention a wealthy smuggler, have anything to do with helping Jews? This is probably a punishable offense in Romania and meant certain death in German-occupied Poland. Only gypsies were desperate enough to offer their services. Even if Nicolescu was willing to help me, I had no money to pay him.

Moreover, those who did pay were often betrayed and delivered to the authorities on one or the other side. There was no guarantee of success, and many lost their lives in the attempt. A few days earlier, I saw a clump of corpses roped to each other floating down the river. I didn’t consider my death an issue anymore, but I was afraid of exposing Ella and the child to the risks involved. I told Chumak to forget it. I couldn’t do it.

“What choice do you have?” Chumak pressed. “Don’t be a fool. You, the woman, and the child definitely won’t survive on this side of the river, and you will stand a better chance over there, as far away as you can get from the Germans.”

His understanding of the situation is correct. The local peasants were handing Jews over for some butter or sugar and an opportunity to steal their belongings. They say a drowning man will grasp at a razor blade to save himself, so I agree.

“Even if I manage to make it across, how will I convince him? I have no money.”

Chumak was skeptical about my claim of penury. This wasn’t out of spite that he had thought through but rather an inherited bias. He was of the age-old school that believed Jews always had hidden treasure somewhere. He was convinced that if I couldn’t offer cash immediately, Nicolescu would accept a promise of future payment from a “high-class” Jew like me. To me, this appeared to be just wishful thinking since Chumak admitted never having actually done business with this Romanian smuggler, who was out of his league.

Chumak remained adamant, and his confident tone was hard to resist. “Tell your woman to write that she comes from an important, prosperous family in Romania that will pay him generously for his efforts. Give him a written guarantee.”

Before I could change my mind, he produced a slightly greasy lined sheet of paper from a child’s copybook and a blunt pencil stub. I took it to our hideout in the nearby forest, where I cajoled Ella, who also thought the plan was absurd and not doable, into writing the requisite supplication and promise of reward.

Standing on the flat terrain on this side of the river, I realize that the current took me downstream, and I need to walk back to the Nicolescu house. I’m not sure how far it is, but at least I can see where I’m going in the moonlight. I find some stones and strike them together three times, as I promised Chumak, hoping that he hears me, and goes back to report to Ella. Not expecting a response, I walk close to the tree line, off the riverbank pathway used by locals and military patrols. When a searchlight sweeps the river from the Polish side, I scamper into the trees, waiting, breathing hard, and picking up a dead branch for self-defense. Going forward, I detour through the woods to avoid a small group of men sitting by the embers of a fire smoking and passing around a bottle. Hunters or fishermen, I believe.

The house lies ahead through the gate of a stone-walled enclosure. No light escapes from the windows. Nearby in the compound, there are two thatched-roof peasant huts, weak light emanating from one of the windows, and a barn where a horse nickers. I stop to consider which building would be best to approach, and then, as I take a step closer, the dogs come at me, snarling. I fend them off with the branch, hitting one of them in the head. It runs off whimpering while the others keep their distance, growling, and barking. I’m done for. They are going to wake everyone. I retreat into the adjacent cornfield, crouching there cold, miserable, and afraid, as a woman appears holding a lantern outside one of the huts. She calls off the dogs and shoos them into the barn. As she locks the barn door, she stares into the darkness in my direction before going to draw water from a well in the yard and returning to the hut.

I can’t stay here much longer as indecision eats away at my remaining determination. It’s time to make a move, either forward to Nicolescu, whatever the risk and chances of success, or back across the river in abject failure. I run to the hut showing light and knock hesitantly. The dogs continue barking hysterically in the barn. Nothing happens, and I try again more decisively.

“Who’s there,” asks a muffled woman’s voice in Ukrainian.

“It’s me,” I reply. What else could I say?

She opens the door a crack. People must be accustomed to seeing strange sights around here because she doesn’t slam the door in the face of the wet, disheveled, half-naked specter that stands before her.

“What do you want? Who are you looking for?” the woman asks as if I was routinely passing by.

“I have an important letter for Mr. Nicolescu. He needs to see it,” I say, also in Ukrainian.

She invites me into the hut. Alone in the single, earthen floor room, she wears widow’s black. Wrinkeled but unbent, her age is indeterminate. Most of the space in the room is taken up by a traditional wooden loom, while a large blackened icon of the Savior hangs above a stove. I rarely devoted attention to Christian symbols, having never, so far, entered a church and always hurrying by the ubiquitous roadside shrines in our vicinity with eyes averted. The narrative of Christianity and Christians as moral and physical threats was, since time immemorial part of our Jewish psyche, but I have no direct personal experience of it. Even the murder of my father by Jew-hating thugs, which undoubtedly weighed heavily on my perception of the people who surrounded us, didn’t feel like a religious issue. Now though, as I stand here shivering, Jesus on the cross seems to be observing me ominously. But, immediately, my attention is drawn away to a piece of bread on a side table, and without invitation, I grab it and chew hungrily. The woman sees that I am exhausted and soaked and tells me to sit and rest. She brings me a blanket and pours a cup of water, watching silently as I continue chewing the bread thoroughly.

When I finish, she says, “You are from over there. You’re a Jew.” It’s not posed as a question, and she clearly knows why I have come. I’m not the first desperate Jew who has shown up on her doorstep. To my relief, she doesn’t take long to make her decision. “I will take you to Mr. Nicolescu’s mother. She lives in the other hut. Maybe she will help you.”

“Thank you.” I’m wary of digging too deeply into the subject for fear of treading on sensitive toes, but I’m also anxious to find out what has happened on this side of the river and know what to expect if Ella and Sophie are to cross with me later. “Are there any Jews left around here?” I ask warily. “What about the Jews in the city?”

“They got rid of all our Jews,” she replies in a matter-of-fact tone. “They say the devil came for them. You need to watch out.”

“Come,” she beckons. “We should go to Nicolescu’s mother before anyone else sees you here. People won’t hesitate to give you up.” I follow her to the neighboring hut, where a tall, old woman approaches us. “Who is that with you, Bohuslava?” she calls out in Romanian. “Beware of robbers. I’ll get a stick and run him off.”

Bohuslava walks over to her. “Shh, be quiet,” she says in Ukrainian. “Stop fussing. He means no harm and just wants to show you something. “Come here quickly,” she gestures to me.

Grey-haired, slightly stooped, with one eye clouded by a cataract, she must be in her seventies but looks far from frail. She takes my hand with a firm grip. “Let’s go inside,” she says.

She lights a kerosene lamp. This is a much bigger and well-appointed abode with an ornate porcelain stove dominating the room and a dining table covered in a hand-embroidered red and white tablecloth. Adjacent to the stove stands a single bed occupied by a young woman sleeping, oblivious to us.

“Bohuslava, you may go,” the Romanian says. “Just keep your mouth shut, or it won’t be long before everybody is aware that you take in Jewish strays. We don’t need that kind of trouble.”

“What will I say?” answers the other woman on her way out. “That you have a new lover and a Jewish one at that,” she cackles.

“Sit,” the tall woman says, pointing to a chair beside the table. Like most Romanians living on the border, she is fluent in Ukrainian, while my Romanian is rudimentary at best. “Show me what you brought,” she asks. I remove it from the pig’s bladder and hand the grotty piece of paper to her. She dons reading glasses and concentrates on the message.

“Good Romanian,” is her first reaction. “Who wrote it? It couldn’t be you.”

“My wife,” I say tersely.

“Is she from around here?”

“She is from the city,” I reply. “Actually, we’re together but not officially married. She has a small child, her daughter, with her. They were forced across the river with others a few months ago, and we are trying to get back to the city to join relatives who might still be there. The situation on the other side of the river is deadly.”

“Yes, I know. It’s not really safe here, either. If you’re caught, they will send you back there without a second thought. Don’t expect much pity here because nobody wants to get in trouble for hiding Jews from the authorities.”

Not wanting to get into a discussion on motivations. I prefer to get to the point. “I was told that your son, Domnul Nicolescu, has experience getting people across the river. If your son could help us, we will take our chances. It’s preferable to certain death over there.”

“I can’t speak for him,” she says. “He is a good man, but I doubt, though, that he would be willing to take such a great risk. He was never involved in the smuggling of people across the border. It’s a bad business. For him, it has always been cigarettes and other contraband.”

I am surprised, honestly, that she speaks so openly of her son’s activities to a stranger… especially to one with a price on his head. Though she doesn’t hold out hope, her demeanor and attitude give me a sliver of confidence. “You should get some rest,” she suggests, “and I will take you to him in the morning.”

“What is your name?” I ask.

“Margareta. And yours?”

“I am Emil. Thank you, Doamna Margareta, for your kindness. I hope your son takes after you.”

She wakes the girl rudely and pushes her into the other room. “Here, take this bed. The servant girl can sleep in my room. I will leave some dry clothes for you and wake you when we need to go.”

“Thank you again. Good night.” I kiss her hand.

“Good night, Domnule Emil. Sleep well.”

I feel exhausted and drained, and my shriveled muscles ache from the unaccustomed effort of swimming across the water, but sleep remains elusive. It’s not the discomfort of the thin, lumpy mattress and the scratchy wool blanket that still hold the sour odor of their previous user, nor is it the constant, sometimes frantic, barking of dogs outside that keep rest at bay. By now, I’m also habituated to grasping moments of sleep in more dire circumstances, whether in the camp barracks or on the cold forest floor. Tonight I’m kept wide awake by the train of thoughts and questions running in a relentless loop through my mind. Are Ella and Sophie safe on the other side, alone with the Chumaks? Will Nicolescu agree to help without payment in advance? Will we be betrayed by the smuggler as so many have been before us? What lies in store for us on this side without any means for survival at our disposal? Should we hide in the countryside here or take the risk of heading for the city? I try to block out the most subversive, monstrous, cowardly, and tempting considerations, but they are there. The palpable fear of swimming back across the river toward the near certainty of death, tries to convince me that I’m now safer and that on my own, I stand a better chance of hiding and surviving. Yes, I would be abandoning Ella and Sophie, but by going back, I would only join them in being captured and killed. They would be safer staying with the Chumaks, who certainly would take pity and continue to conceal and support a defenseless woman and child. Or maybe I could remain here and just send the smuggler for them. I want to scream. I will go back.

The sun is up when Margareta nudges me awake and offers me a mug of hot tea while waiting as I put on the clothes she brought. They belong to a larger man, but they will have to do. I walk with her to the door of the house. A few people, already out and about, are on their way to work in the fields, some leading cattle and a flock of sheep. The men doff their hats and greet her, paying no attention to me.

Margareta instructs me to wait outside and enters without knocking. I hear raised voices inside. “Have you lost your mind? Why did you bring him here? Do you want to get us arrested? Send him away!” A few moments later, Margareta reappears with another woman, a pale ash blonde of about forty, holding a cigarette in her long elegant fingers with a worried look on her face — definitely not of the farming class. The woman scans the yard nervously.

“My mother-in-law told me what you want. I am sorry, but Mr. Nicolescu doesn’t do this business. We cannot do anything for you.” Her voice trembles and she is obviously terrified. “Anyway, he is not here. He is in the city, and I don’t know when he will be back. You must go. It’s dangerous here, and you will get us into trouble. Please go now.” She starts to retreat into the house.

I can’t hold her against her will, and if Nicolescu is indeed away, there is nothing more to be gained here. “Thank you, Doamna Nicolescu,” I say in Romanian and press my luck. “I will go, but could you kindly give me some bread?”

She goes inside and is soon back with half of a large loaf. I once again kiss her well-manicured hand and turn to leave.

“Mr. Emil,” says Margareta, “You should not wander around here in daylight. It’s dangerous to stay out in the open. Why don’t you hide in the barn till dark? It will be safer that way.”

“Again, you are so kind, Madame, but I must return to my family. It has been too long already. They are alone and will worry that something bad has happened to me. I will be as careful as I can.”

“Very well, if you must, but follow me.” She leads me into the forest on a narrow footpath that is a roundabout way down to the water’s edge. “Eat the bread, you need the strength, and it will be ruined in the water,” she says. I need no more encouragement as I almost choke, devouring it. She turns to leave. “Be careful, Emil, and good luck to you. I will talk to Nicolescu when he returns. Maybe he will agree to help. He has more conscience than that frightened ornament he calls his wife. How can he find you?”

“There is a peasant named Chumak. He knows where we are,” I tell her.

“Yes, Chumak. I know him. He also used to smuggle cigarettes before the war.”

“Thank you, Madame. I will remember your generosity.” She is gone.

I sit brooding among the trees looking at the river as the sun glints off the streaming water and listening to cheerful birds chirping. I can’t help but ponder the difference between the elderly women, Bohuslava and Margareta, and the wife of Nicolescu. I’m not surprised by the younger woman’s reaction. It is one version, slightly less brusque, of the general refusal to help Jews. But, all other considerations aside, who can blame people for fearing the fatal punishments meted out by the Germans and their Ukrainian lackeys to so-called Jew-lovers? Would I behave any differently in their shoes? I am more impressed, not to say astonished, by those candles in the darkness, people who have everything to lose, yet whose basic humanity causes them to stretch out their hands to support their fellow men and women. That rough peasant Chumak, whose whole universe is his tiny homestead next to an unknown village on the banks of the river, heads my list of the righteous. Now I add Bohuslava and Margareta to it. The existence of such people, beyond their contribution to our physical safety, keeps alive my essential positivity toward humankind and allows me to still retain some belief in our survival.

What next, I ask myself? I achieved nothing and have no other plan in reserve. Swimming back in broad daylight now seems suicidal. Maybe drowning is a good option? But that means abandoning Ella and the child, and I have already decided this is not an option. Bring back yesterday’s rain, I pray. I pray, though my belief in the idea of an Almighty, never cast-iron, has been dramatically undermined by the past year’s events. Then the wind picks up, and the miracle unfolds. Dark clouds scud across the sky, and the first drops wet my face, replacing the tears. In moments the downpour becomes torrential. I tie the new clothes around my neck and dive into the river, feeling more energetic on my way back. The current is slow enough for me to gradually dog-paddle most of the way across and finish with a few crawl strokes.

I’m carried only about a half-kilometer downstream, and elation replaces caution as I drag myself onto the riverbank and start walking. Climbing up the steep slope, Chumak’s hut is soon ahead, but when I approach and enter it, nobody is there. I look for Ella and Sophie, but the barn is empty too, and figuring that Chumak is probably out working in the field, I continue upwards into the forest towards our erstwhile hiding place. Ella and Sophie are supposed to wait there for me in case of trouble. I call out not to surprise them but there is no reply. I run to the hideout. They are gone.

Features

So, what’s the deal with the honey scene in ‘Marty Supreme?’

By Olivia Haynie December 29, 2025 This story was originally published in the Forward. Click here to get the Forward’s free email newsletters delivered to your inbox.

There are a lot of jarring scenes in Marty Supreme, Josh Safdie’s movie about a young Jew in the 1950s willing to do anything to secure his spot in table tennis history. There’s the one where Marty (Timothée Chalamet) gets spanked with a ping-pong paddle; there’s the one where a gas station explodes. And the one where Marty, naked in a bathtub, falls through the floor of a cheap motel. But the one that everybody online seems to be talking about is a flashback of an Auschwitz story told by Marty’s friend and fellow ping-ponger Béla Kletzki (Géza Röhrig, best known for his role as a Sonderkommando in Son of Saul).

Kletzki tells the unsympathetic ink tycoon Milton Rockwell (Kevin O’Leary) about how the Nazis, impressed by his table tennis skills, spared his life and recruited him to disarm bombs. One day, while grappling with a bomb in the woods, Kletzki stumbled across a honeycomb. He smeared the honey across his body and returned to the camp, where he let his fellow prisoners lick it off his body. The scene is a sensory nightmare, primarily shot in close-ups of wet tongues licking sticky honey off Kletzki’s hairy body. For some, it was also … funny?

Many have reported that the scene has been triggering a lot of laughter in their theaters. My audience in Wilmington, North Carolina, certainly had a good chuckle — with the exception of my mother, who instantly started sobbing. I sat in stunned silence, unsure at first what to make of the sharp turn the film had suddenly taken. One post on X that got nearly 6,000 likes admonished Safdie for his “insane Holocaust joke.” Many users replied that the scene was in no way meant to be funny, with one even calling it “the most sincere scene in the whole movie.”

For me, the scene shows the sheer desperation of those in the concentration camps, as well as the self-sacrifice that was essential to survival. And yet many have interpreted it as merely shock humor.

Laughter could be understood as an inevitable reaction to discomfort and shock at a scene that feels so out of place in what has, up to that point, been a pretty comedic film. The story is sandwiched between Marty’s humorous attempts to embarrass Rockwell and seduce his wife. Viewers may have mistaken the scene as a joke since the film’s opening credits sequence of sperm swimming through fallopian tubes gives the impression you will be watching a comedy interspersed with some tense ping-pong playing.

The reaction could also be part of what some in the movie theater industry are calling the “laugh epidemic.” In The New York Times, Marie Solis explored the inappropriate laughter in movie theaters that seems to be increasingly common. The rise of meme culture and the dissolution of clear genres (Marty Supreme could be categorized as somewhere between drama and comedy), she writes, have primed audiences to laugh at moments that may not have been meant to be funny.

The audience’s inability to process the honey scene as sincere may also be a sign of a society that has become more disconnected from the traumas of the past. It would not be the first time that people, unable to comprehend the horrors of the Holocaust, have instead derided the tales of abuse as pure fiction. But Kletzki’s story is based on the real experiences of Alojzy Ehrlich, a ping-pong player imprisoned at Auschwitz. The scene is not supposed to be humorous trauma porn — Safdie has called it a “beautiful story” about the “camaraderie” found within the camps. It also serves as an important reminder of all that Marty is fighting for.

The events of the film take place only seven years after the Holocaust, and the macabre honey imagery encapsulates the dehumanization the Jews experienced. Marty is motivated not just by a desire to prove himself as an athlete and rise above what his uncle and mother expect of him, but above what the world expects of him as a Jew. His drive to reclaim Jewish pride is further underscored when he brings back a piece of an Egyptian pyramid to his mother, telling her, “We built this.”

Without understanding this background, the honey scene will come off as out of place and ridiculous. And the lengths Marty is willing to go to to make something of himself cannot be fully appreciated. The film’s description on the review-app Letterboxd says Marty Supreme is about one man who “goes to hell and back in pursuit of greatness.” But behind Marty is the story of a whole people who have gone through hell; they too are trying to find their way back.

Olivia Haynie is an editorial fellow at the Forward.

This story was originally published on the Forward.

Features

Paghahambing ng One-on-One Matches at Multiplayer Challenges sa Pusoy in English

Ang Pusoy, na kilala din bilang Chinese Poker, ay patuloy na sumisikat sa buong mundo, kumukuha ng interes ng mga manlalaro mula sa iba’t ibang bansa. Ang mga online platforms ay nagpapadali sa pag-access nito. Ang online version nito ay lubos na nagpasigla ng interes sa mga baguhan at casual players, na nagdulot ng diskusyon kung alin ang mas madali: ang paglalaro ng Pusoy one-on-one o sa multiplayer settings.

Habang nailipat sa digital platforms ang Pusoy, napakahalaga na maunawaan ang mga format nito upang mapahusay ang karanasan sa laro. Malaking epekto ang bilang ng mga kalaban pagdating sa istilo ng laro, antas ng kahirapan, at ang ganap na gameplay dynamics. Ang mga platforms tulad ng GameZone ay nagbibigay ng angkop na espasyo para sa mga manlalaro na masubukan ang parehong one-on-one at multiplayer Pusoy, na akma para sa iba’t ibang klase ng players depende sa kanilang kasanayan at kagustuhan.

Mga Bentahe ng One-on-One Pusoy

Simpleng Gameplay

Sa one-on-one Pusoy in English, dalawa lang ang naglalaban—isang manlalaro at isang kalaban. Dahil dito, mas madali ang bawat laban. Ang pokus ng mga manlalaro ay nakatuon lamang sa kanilang sariling 13 cards at sa mga galaw ng kalaban, kaya’t nababawasan ang pagiging komplikado.

Para sa mga baguhan, ideal ang one-on-one matches upang:

- Sanayin ang tamang pagsasaayos ng cards.

- Matutunan ang tamang ranggo ng bawat kamay.

- Magsanay na maiwasan ang mag-foul sa laro.

Ang simpleng gameplay ay nagbibigay ng matibay na pundasyon para sa mas kumplikadong karanasan sa multiplayer matches.

Mga Estratehiya mula sa Pagmamasid

Sa one-on-one matches, mas madaling maunawaan ang istilo ng kalaban dahil limitado lamang ang galaw na kailangan sundan. Maaari mong obserbahan ang mga sumusunod na patterns:

- Konserbatibong pagkakaayos o agresibong strategy.

- Madalas na pagkakamali o overconfidence.

- Labis na pagtuon sa isang grupo ng cards.

Dahil dito, nagkakaroon ng pagkakataon ang mga manlalaro na isaayos ang kanilang estratehiya upang mas epektibong maka-responde sa galaw ng kalaban, partikular kung maglalaro sa competitive platforms tulad ng GameZone.

Mas Mababang Pressure

Dahil one-on-one lamang ang laban, mababawasan ang mental at emotional stress. Walang ibang kalaban na makaka-distract, na nagbibigay ng pagkakataon para sa mga baguhan na matuto nang walang matinding parusa sa kanilang mga pagkakamali. Nagiging stepping stone ito patungo sa mas dynamic na multiplayer matches.

Ang Hamon ng Multiplayer Pusoy

Mas Komplikado at Mas Malalim na Gameplay

Sa Multiplayer Pusoy, madaragdagan ang bilang ng kalaban, kaya mas nagiging komplikado ang laro. Kailangan kalkulahin ng bawat manlalaro ang galaw ng maraming tao at ang pagkakaayos nila ng cards.

Ang ilang hamon ng multiplayer ay:

- Pagbabalanse ng lakas ng cards sa tatlong grupo.

- Pag-iwas sa labis na peligro habang nagiging kompetitibo.

- Pagtatagumpayan ang lahat ng kalaban nang sabay-sabay.

Ang ganitong klase ng gameplay ay nangangailangan ng maingat na pagpaplano, prediksyon, at strategic na pasensiya.

Mas Malakas na Mental Pressure

Mas mataas ang psychological demand sa multiplayer, dahil mabilis ang galawan at mas mahirap manatiling kalmado sa gitna ng mas maraming kalaban. Kabilang dito ang:

- Bilisan ang pagdedesisyon kahit under pressure.

- Paano mananatiling focused sa gitna ng mga distractions.

- Pagkakaroon ng emosyonal na kontrol matapos ang sunod-sunod na talo.

Mas exciting ito para sa mga manlalarong gusto ng matinding hamon at pagmamalasakit sa estratehiya.

GameZone: Ang Bagong Tahanan ng Modern Pusoy

Ang GameZone online ay isang kahanga-hangang platform para sa mga naglalaro ng Pusoy in English. Nagbibigay ito ng opsyon para sa parehong one-on-one at multiplayer matches, akma para sa kahit anong antas ng kasanayan.

Mga feature ng GameZone:

- Madaling English interface para sa user-friendly na gameplay.

- Real-player matches imbes na kalaban ay bots.

- Mga tool para sa responsible play, tulad ng time reminder at spending limits.

Pagtatagal ng Pamanang Pusoy

Ang Pusoy card game in English ay nagpalawak ng abot nito sa mas maraming players mula sa iba’t ibang bahagi ng mundo habang pinapanatili ang tradisyunal nitong charm. Sa pamamagitan ng mga modernong platform tulad ng GameZone, mananatiling buhay at progresibo ang Pusoy, nakakabighani pa rin sa lahat ng antas ng manlalaro—mula sa casual enjoyment hanggang sa competitive challenges.

Mula sa maingat na pag-aayos ng mga cards hanggang sa pag-master ng estratehiya, ang Pusoy ay isang laro na nananatiling relevant habang ipinapakita ang masalimuot nitong gameplay dynamics na puno ng kultura at inobasyon.

Features

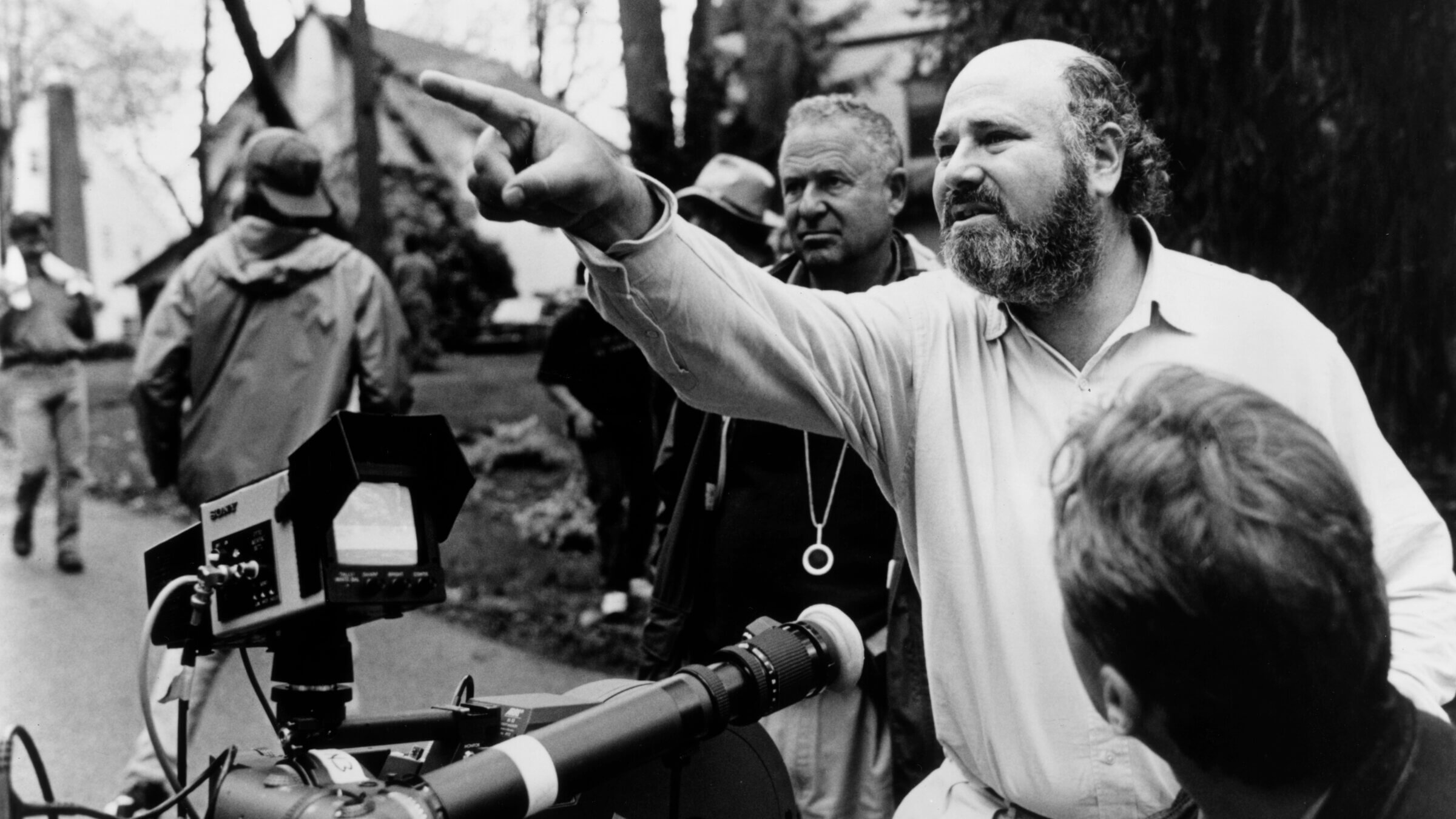

Rob Reiner asked the big questions. His death leaves us searching for answers.

Can men and women just be friends? Can you be in the revenge business too long? Why don’t you just make 10 louder and have that be the top number on your amp?

All are questions Rob Reiner sought to answer. In the wake of his and his wife’s unexpected deaths, which are being investigated as homicides, it’s hard not to reel with questions of our own: How could someone so beloved come to such a senseless end? How can we account for such a staggering loss to the culture when it came so prematurely? How can we juggle that grief and our horror over the violent murder of Jews at an Australian beach, gathered to celebrate the first night of Hanukkah, and still light candles of our own?

The act of asking may be a way forward, just as Rob Reiner first emerged from sitcom stardom by making inquiries.

In This is Spinal Tap, his first feature, he played the role of Marty DiBergi, the in-universe director of the documentary about the misbegotten 1982 U.S. concert tour of the eponymous metal band. He was, in a sense, culminating the work of his father, Carl Reiner, who launched a classic comedy record as the interviewer of Mel Brooks’ 2,000 Year Old Man. DiBergi as played by Reiner was a reverential interlocutor — one might say a fanboy — but he did take time to query Nigel Tufnell as to why his amp went to 11. And, quoting a bad review, he asked “What day did the Lord create Spinal Tap, and couldn’t he have rested on that day too?”

But Reiner had larger questions to mull over. And in this capacity — not just his iconic scene at Katz’s Deli in When Harry Met Sally or the goblin Yiddishkeit of Miracle Max in The Princess Bride — he was a fundamentally Jewish director.

Stand By Me is a poignant meditation on death through the eyes of childhood — it asks what we remember and how those early experiences shape us. The Princess Bride is a storybook consideration of love — it wonders at the price of seeking or avenging it at all costs. A Few Good Men is a trenchant, cynical-for-Aaron Sorkin, inquest of abuse in the military — how can it happen in an atmosphere of discipline.

In his public life, Reiner was an activist. He asked how he could end cigarette smoking. He asked why gay couples couldn’t marry like straight ones. He asked what Russia may have had on President Trump. This fall, with the FCC’s crackdown on Jimmy Kimmel, he asked if he would soon be censored. He led with the Jewish question of how the world might be repaired.

Guttingly, in perhaps his most personal project, 2015’s Being Charlie, co-written by his son Nick he wondered how a parent can help a child struggling with addiction. (Nick was questioned by the LAPD concerning his parents’ deaths and was placed under arrest.)

Related

None of the questions had pat answers. Taken together, there’s scarcely a part of life that Reiner’s filmography overlooked, including the best way to end it, in 2007’s The Bucket List.

Judging by the longevity of his parents, both of whom lived into their 90s, it’s entirely possible Reiner had much more to ask of the world. That we won’t get to see another film by him, or spot him on the news weighing in on the latest democratic aberration, is hard to swallow.

Yet there is some small comfort in the note Reiner went out on. In October, he unveiled Spinal Tap II: The Beginning of the End, a valedictory moment in a long and celebrated career.

Reiner once again returned to the role of DiBergi. I saw a special prescreening with a live Q&A after the film. It was the day Charlie Kirk was assassinated. I half-expected Reiner to break character and address political violence — his previous film, God & Country, was a documentary on Christian Nationalism.

But Reiner never showed up — only Marty DiBergi, sitting with Nigel Tuffnell (Christopher Guest), David St. Hubbins (Michael McKean) and Derek Smalls (Harry Shearer) at Grauman’s Chinese Theater in Los Angeles. The interview was broadcast to theaters across the country, with viewer-submitted questions like “What, in fact, did the glove from Smell the Glove smell like?” (Minty.) And “Who was the inspiration for ‘Big Bottom?’” (Della Reese.)

Related

- Actor-Director Rob Reiner dies at 78

- Carl Reiner On Judaism, Atheism And The ‘Monster’ In The White House

- Mandy Patinkin On His Favorite ‘Princess Bride’ Quote

DiBergi had one question for the audience: “How did you feel about the film?”

The applause was rapturous, but DiBergi still couldn’t get over Nigel Tuffnell’s Marshall amp, which now stretched beyond 11 and into infinity.

“How can that be?” he asked. “How can you go to infinity? How loud is that?”

There’s no limit, Tuffnell assured him. “Why should there be a limit?”

Reiner, an artist of boundless curiosity and humanity, was limitless. His remit was to reason why. He’ll be impossible to replace, but in asking difficult questions, we can honor him.

The post Rob Reiner asked the big questions. His death leaves us searching for answers. appeared first on The Forward.